What is a Deltoid Muscle Pain?

Deltoid muscle pain is a common complaint that can significantly impact daily activities and overall quality of life. The deltoid muscle, located on the uppermost part of the arm and shoulder, plays a crucial role in various movements such as lifting, rotating, and stabilizing the arm. Pain in this muscle can arise from a variety of causes, including overuse, injury, or underlying medical conditions.

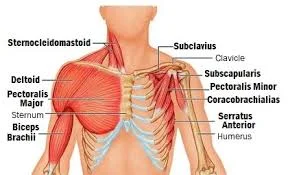

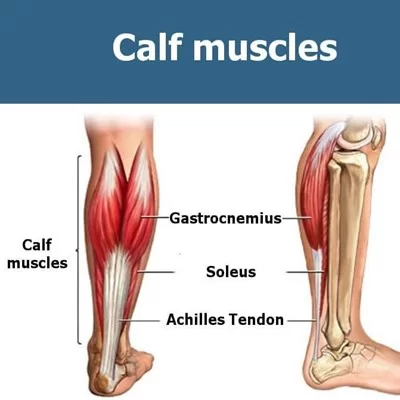

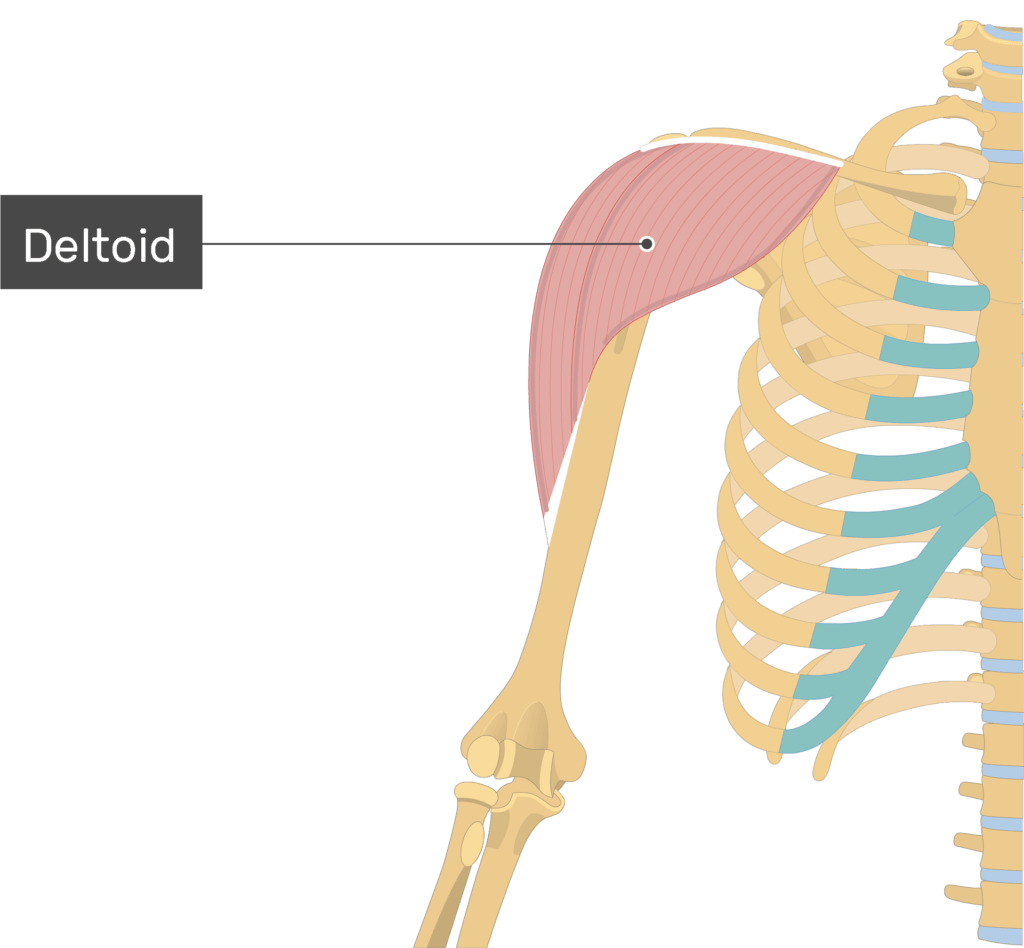

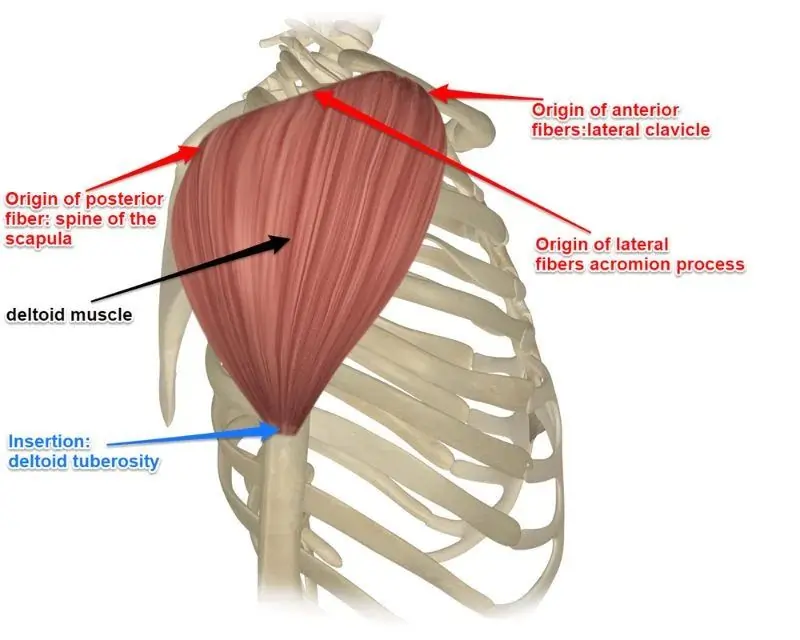

The Deltoid muscle: The muscular structure that gives the shoulder its rounded shape is the Deltoid, a big, triangular muscle situated over the glenohumeral joint.

- It is comprised of three distinct portions

- anterior or clavicular,

middle or acromial,

and posterior or spinal

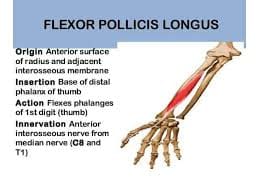

Anatomy

- Origin:

- Anterior border

- an upper surface of lateral1/3 of the Clavicle (clavicular part),

- The spine of the Scapula (spinal part)

- Acromion (acromial part),

- Insertion:

- In the humerus, it goes into the deltoid tuberosity

- Nerve:

- Axillary nerve (C5, C6) ,

- The deltoid muscle primarily serves as the humeral head stabilizer and shoulder abductor. further supports forward elevation

- The deltoid is a very strong muscle of the shoulder joint which used in many ADL activities and athletic activities. (eg netball, swimming,

- Around the top of the upper arm and shoulder is a round muscle called the deltoid.

Function:

- The deltoid muscle’s primary function is to assist in lifting and rotating the arm.

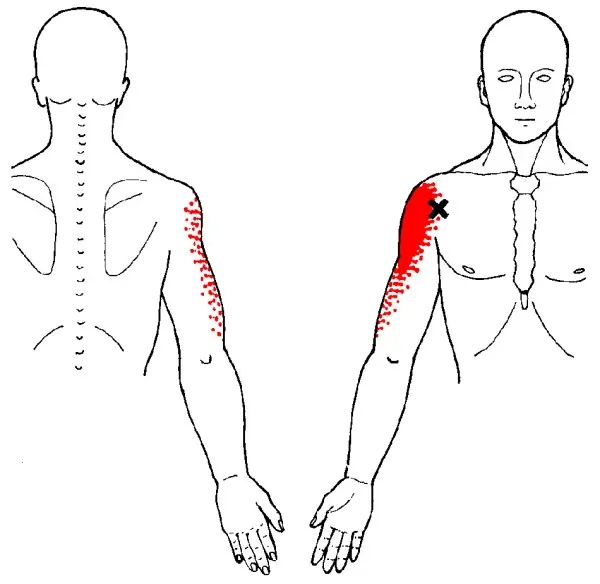

deltoid muscle pain feels mainly in the shoulder and is experienced during shoulder movements such as lifting or carrying. - Deltoid muscle strain and overuse are the causes of this muscle stiffness.

There’s pain and swelling in the deltoid muscle. - If the patient feels that the pain has many causes, including neck issues, arthritis, and other medical conditions.

However, if the pain is coming from the shoulder joint’s side, front, or back, it is most often caused by a deltoid muscle injury, which occurs when lifting the arm. - For some emergency signs please get in touch with the doctor.

What is deltoid muscle?

- The deltoid is known as the thick, triangular shoulder muscle known as the deltoid.

Because of how similar it is to the Greek letter “delta,” this muscle is known as the deltoid

This muscle’s broad origin includes the clavicle, acromion, and scapular spine. - It enters into the humerus after passing inferiorly through the region surrounding the glenohumeral joint (GH joint).

The acromial, clavicular, and scapular spinal segments combine to produce the deltoid muscle.

the deltoid.

- The acromial part = middle fibers that abduct the arm, while the clavicular & scapular spinal parts play a significant role in the stabilization, ensuring the steady plane of the abduction movement.

- The clavicular part = Anterior fibers function as the arm’s flexor and internal rotator (IR).

- The scapular Part=muscles in the posterior region that stretch and rotate the arm externally.

Deltoid muscle Pain

- Deltoid muscle pain feels mainly in the shoulder and is experienced during shoulder movements such as lifting or carrying.

- Deltoid muscle strain and overuse are the main causes of this muscle stiffness which also cause

pain and swelling in the deltoid muscle.

- One of the more typical “problem areas” of the shoulder joint is thought to be the deltoid.

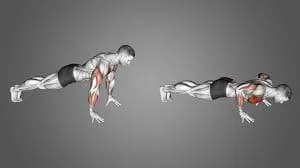

- The most common activities that cause injuries to the deltoid are lifting, reaching back, throwing overhead, and even raising weights while performing exercises like push-ups and pull-ups.

- Here, we’ve covered the causes, symptoms, and deltoid discomfort as well as cures and therapies to assist you in getting clear of the pain.

What is the cause of deltoid muscle pain?

- The most frequent causes of deltoid muscle pain are sprains and overuse injuries to the shoulder.

Athletes and other people who frequently use their shoulder and deltoid muscles are more likely to suffer from soft tissue injuries and deltoid pain. Another cause of muscle spasms is a shoulder dislocation. - Deltoid strain can happen suddenly as a result of an accident, such as tripping or heavy lifting, resulting in acute pain.

- The majority of deltoid injuries occur gradually over time and are especially caused by sports like baseball, swimming, and weightlifting.

- Individuals who experience shoulder bursitis (bursa is a thin, fluid-filled sac that provides a cushioning effect) generally also get shoulder tendinitis in which injury to rotator cuff tendons occurs because of its rubbing, known as the acromion, between the humerus and the upper outer edge of the shoulder This condition happens in impingement syndrome.

Other:

- Not warming up properly before physical exercise

- Poor flexibility

- Poor exercise

- Overexertion and fatigue

- Weakness

- Acute injuries cause a macro-trauma to the muscle and usually represent the outcome of a single traumatic event. There is a clear connection between the symptoms and the cause. They play contact sports with a high strike rate and are dynamic, much like tennis and baseball. A strain might result from moving or turning the elbow and shoulder oddly or unexpectedly.

- The Deltoid muscle is overused.

Repetitive movements

Prolonged weight bearing or stress (e.g., wearing a large backpack) is applied to the deltoid muscle, which hurts and damages the muscle.

There is a greater chance of straining the deltoid muscle in sports and other activities that involve repetitive movements, like tennis, swimming, and other hobbies.

Acute trauma

The deltoid muscle is experiencing sudden pressure or trauma, which is producing a tear in the patient.

This occurs when one lifts excessive weight or breaks a fall with an outstretched arm.

Poor posture

Variations in posture affect the shoulder joint’s range of motion, the location of the humerus, and the degree to which the joint’s components function as a unit.

These additional pressures cause the muscle to become more strained over time, which results in pain and decreased movement.

Poor flexibility

Warming up, cooling down, and stretching are essential before starting any type of activity.

By doing this, the deltoid will be more protected. Stretches focusing on the deltoid and shoulder muscles will increase flexibility and help avoid injuries.

What are the Symptoms of the deltoid muscle pain?

- The patient usually feels deltoid pain/soreness. (especially in the morning)

An unexpected pain in the arm’s front side.

Tenderness or pain near the deltoid muscle

Your deltoid experiences a snapping or popping feeling. - bruises and swelling in the deltoid muscle.

Restricted deltoid muscle mobility.

spasms in the deltoid muscle.

weakening of the muscles.

tightness in the muscles.

Other Symptoms depend on the severity of the strained muscle.

Three grades of strains to the deltoid muscle can be identified.

- Grade one – 1

- If the patient presents a grade one strain, the patient uses the arm normally but has some tightness/soreness in the shoulder.

- The shoulder joint is slightly swollen.

- Using the arm produces slight pain, but the range of movement [ ROM ] is often not restricted.

- Grade two -2

- When partial tears of the deltoid muscle occur in a patient with Grade 2 strains.

- Using or raising the arm normally is difficult when there is a grade two strain.

- In addition to a somewhat enlarged shoulder joint, the patient has acute pain when attempting to utilize their arm.

- Pressing down or raising the arm in any way when suffering from this condition.

- Grade Third -3

More severe or total deltoid muscle rips occur in grade three strains.

Pulled muscles result in excruciating agony and complete immobility of the arm. - The enlarged shoulder joint is quite large.

The arm is either completely immobile or has very restricted movement due to the pain. - The patient experiences deltoid muscle discomfort, weakness, and tightness.

When the deltoid muscle is injured, the person typically experiences pain and tenderness when lifting their arm and at the front, side, or rear of the shoulder joint.

Should the deltoid muscle be injured and bruising and edema result from it - Restricted to the patient’s ROM (range of motion).

Serious muscular injury might cause problems with regular movement.

It may indicate a frontal muscle injury if the patient finds it difficult to raise their arm or move it 90 degrees to the side of their body.

Raise the arm from the side upwards in response to increased pain to avoid damaging the middle or upper region of the deltoid muscle

Why Do the Deltoid Muscles Hurt After Sleeping?

During sleep, direct pressure is usually applied to your deltoid muscles and other shoulder muscles,

which can create pain when you wake up, especially if you roll over and sleep on the side that is damaged or sore.

When should I consult a physician for pain in the deltoid muscle?

- Severe episodes of shoulder joint pain might be caused by:

- Limit arm mobility completely.

- Should the patient experience a popping sound coming from a muscle

- Continue for a few weeks if the patient feels

- If the severe discomfort interferes with sleep, even when you’re at rest

Diagnosing the deltoid muscle pain

Diagnostic testing is not necessary for the majority of minor or partial muscle strains, but it can assist in determining whether you have a rupture strain and rule out other possible reasons for arm or shoulder pain.

Investigation

X-rays:

An overall two-dimensional image of your upper arm, elbow, and shoulder can be obtained by X-rays. They aid in the diagnosis of instability, unusual

bone forms, avulsion fractures, and other issues.

MRI

provide more details and aid in the assessment of the soft tissues in and surrounding your deltoid.

They can assist in assessing the degree of your injury, the quality of your tear or inflammation, and other conditions that are similar.

They can also detect damage to your tendons or ligaments.

Assessment of deltoid pain

- History along with any related symptoms.

- mechanism of injury.

- triggering trauma’s direction and force of harm.

- Repetitive trauma: injuries associated with poor posture.

Observation

- An evident deformity resembling a bulge or defect in the muscular belly may be the result of strain injuries to the deltoid.

- Tenderness

- Swelling

Treatment of deltoid muscle pain

For immediate pain relief :

- Conservative: Surgery is not necessary for maximum muscular strains, but if the muscle is completely injured, experts advise it.

- Even with a partial cut, athletes can still replace it when they can move and exert themselves normally.

- This usually happens after many weeks to several months of intensive counseling and treatment.

- Surgical treatment may be beneficial for the athlete if the muscle is destroyed.

- When it comes to over-the-counter (OTC) medications like ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB), aspirin, and naproxen sodium (Aleve), some therapists advise against using them for the first 48 hours following a muscle strain because they can increase your risk of bleeding.

- Pain management during this time may be achieved using acetaminophen (Tylenol) and other medications.

- A physiotherapist helps you to increase the strength and stability of the injured joint or limb.

- Deltoid muscle sprint surgery may be necessary for specific muscle injuries.

Easy remedies at home:

To reduce pain and swelling as first aid by following the PRICE star:

- P- Protection

- R- Rest

- I- Ice for cooling

- C- Contraction tapping and splinting

- E- Elevation

the P. R.I.C.E approach

PROTECTION: Protection means to protect the injured part from further movements.

It is usually achieved by keeping the desired area in a protective covering such as a shoulder sling or shoulder brace.

Sometimes a certified sports therapist might perform Kinesio-taping to keep the muscle in a protective stance and reduce the chance of further.

Rest: You need to stop or change the activity that may have caused the shoulder pain.

Ice: Cold compresses can help in shoulder swelling reduction.

Sharp discomfort can also be reduced by cooling. Up to five times a day, apply an ice pack for up to 20 minutes.

Cover the cold pack with a gentle cloth. Avoid touching your skin directly with a cold pack.

Compression: To help with pain and swelling reduction, wrap the shoulder with an elastic medical bandage.

Either use a standard ACE bandage or a cold compression bandage. A pharmacy is another place where you can get a shoulder wrap. Don’t wrap it too tightly, yet firmly.

Avoid obstructing blood flow. Loosen the compression bandage if your hand or arm starts to go numb, tingling, or bluish.

Elevate: The burnt space that allows gravity to help reduce swelling above your heart’s extent, especially around midnight.

One to five days following the injury, or when pain and swelling have reduced, the patient is instructed to aid heat. Giving the shoulder joint some rest during this period will help it heal.

In addition, the patient is using over-the-counter medications to help with pain management.

Applying gentle stretching can help relieve pain caused by deltoid tension.

Raise your clasped hands over your head and try holding the arm across to your chest.

These stretches aid in improving flexibility and range of motion (ROM).

Allowing a greater range of motion in the shoulder joint reduces discomfort.

Immediate treatment According To The Grade Of The Deltoid Strain:

Grade 1 of the deltoid muscle strain:

PRICE protocol with if needed mild painkillers.

- Use a compression bandage and apply ice on a regular basis during the first 24 hours following an injury to minimize swelling.

- Keep the arm in a protective sling and reduce the use of the arm as much as possible.

- After that, apply a heating pad to relieve pain and soreness.

- Allowing the shoulder joint rest is also important.

- After doing this for a day or two, change to gradual isometric contraction.

- Initially, perform 5-7 repetitions with a 3-5 second hold. Gradually increase the reps, hold length, or both, depending on the plan or planned result.

Grade 2 of the deltoid muscle strain:

- PRICE protocol

- over-the-counter anti-inflammatories and painkillers.

- The swelling can be decreased by applying ice regularly for 3-5 days.

- Alternating between ice and heat packs can help reduce pain after an acute muscular injury.

- A compression bandage is put around the arm until the swelling goes down, in addition to the protective sling.

- ROM exercise is started once the initial pain and swelling have subsided. Usually, two to three sets a day, with seven to ten repetitions in each set.

- The patient and physiotherapist work together to gradually expand the range of motion.

- After the patient reaches full range of motion, the next step is strengthening and conditioning,

- which could take several weeks to months, depending on the patient’s needs

- . Here, a physiotherapist prepares a program especially for the needs, objectives, and planned results of that individual patient.

- Give the injury time to heal and reduce back on the regular amount and intensity of exercise during this time.

Grade 3 of the deltoid muscle strain:

- PRICE protocol followed with some painkillers and anti-inflammatories.

- First, a protective cast—such as a shoulder brace—is placed on the injured arm

- After the protection phase is over, the physiotherapist proceeds to the rehabilitation phase,

- progressively increasing the range of motion through several manual techniques before setting a rigorous strength-training plan.

- Before prior strength is reached, the surrounding structures must typically be conditioned as well, which could take months.

- After applying ice to the damage, attempt to avoid using the injured arm and shoulder joint and elevate the affected portion of the area when you can.

- To lessen the suffering, take over-the-counter pain relievers.

- A doctor or rehabilitation professional makes additional advice to control the patient’s pain and expedite recovery if the patient’s discomfort does not go away with time after trying home cures.

Role of Physiotherapy in Deltoid Muscle Pain:

- A Physiotherapist plays an important role in reducing and further preventing deltoid pain.

with the use of electrotherapy and manual therapy, the therapist first works on reducing your pain.

Once that is done, they curate a specially customized program for you based on your needs and goals. - As an example, the physiotherapist may include strength training in the treatment plan for a patient with grade 2 deltoid strain if the patient wants to play with their children.

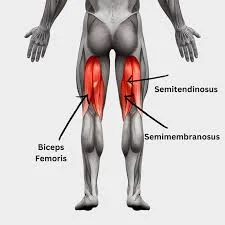

Strength training works all the shoulder muscles, including the rotator cuff, deltoid, joint play, and occasionally even the arm muscles, such as the triceps and biceps.

Rehabilitation program for deltoid pain

Physiotherapy treatment

GOALS FOR TREATMENT:

- Relieve deltoid muscle pain

- Reduce muscle swelling

- Increases deltoid muscle strength

- Improve full mobility of the ligament and joint

- Restore the patient’s confidence

- Restore patients’ full functional activity

Phase one

PRICE PROTOCAL CONTINUE

Electrotherapy

- ultrasound

Ultrasound is used for tissue healing

To increase blood circulation and mobility.

To reduce swelling and pain

- Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy, which involves applying an ice pack and taking a cold bath to the affected area, helps lessen swelling and inflammation.

Applying cold constantly for 15 to 30 minutes at a time, multiple times a day is recommended.

- TENS

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is able to help reduce pain and muscle spasms. - IFT

IFT appears to be used:

Pain relief

Muscle stimulation

Increased local blood flow

Reduction of edema

Phase two

Electrotherapy

As the patient feels pain start exercise

active exercise for a few days can be start

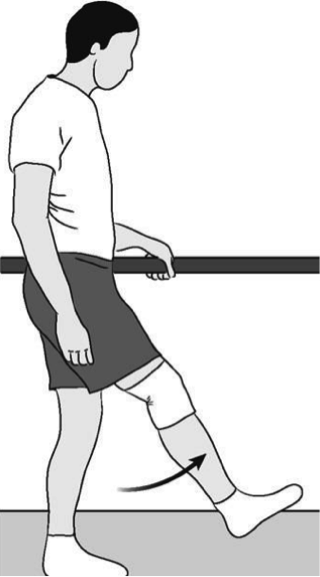

Mobility exercises: level: 1

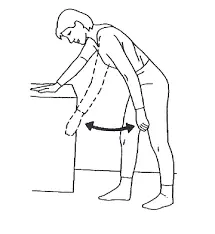

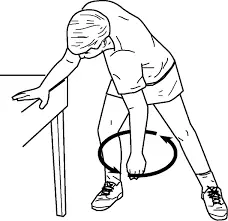

(A) Pendular Exercises

This exercise divided into 4 parts

To perform these exercises: Bend forward and rest your unaffected arm on a table or chair. Relax the painful arm and let it hang down straight.

Part 1: Slowly start to swing the straight arm forward and backward.

Do this for at least 5 minutes.

Start with a small motion and as you become stronger try and increase the range of movement in the forward and backward motion.

Part 2: Begin to swing the straight arm side to side gradually. Work on this for at least five minutes, or until you are no longer able to.

Begin with modest motions and work your way up to a broader range of motion as your strength increases.

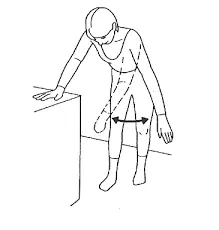

Part 3: Swing the straight arm slowly in a clockwise motion. Work on this for at least five minutes, or until you are no longer able to. Once you gain strength,

aim to extend the circular movement’s range of motion by starting with a smaller motion

Part 4: Begin to slowly rotate the straight arm in the opposite direction of the clock. Work on this for at least five minutes, or until you are no longer able to. Once you gain strength, strive to extend the circular movement’s range of motion by starting with smaller motions.

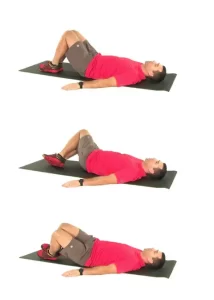

level: 2 Short Lever Exercises in Lying

( A) Shoulder Flexion (Short Lever)

- To perform this exercise, lie on your back and place a rolled towel under the elbow of the arm that pains.

- Extend your elbow as much as possible. Your elbow should point straight up towards the ceiling as you shift your shoulder.

- If you are having difficulty lifting your painful arm, you can use your other arm to assist; but when lifting the painful arm, try to ensure that your shoulder muscles are

- Doing the majority of the effort. going back to where you start.

- Try to complete this for a total of five minutes, or until you feel exhausted and unable to perform anymore. For this exercise, five sets of sixty seconds are advised.

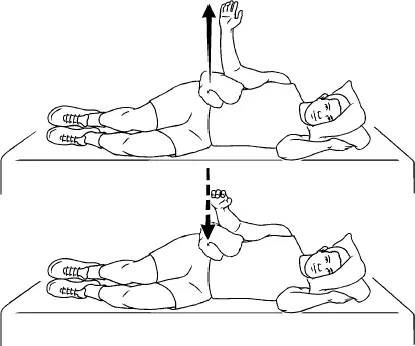

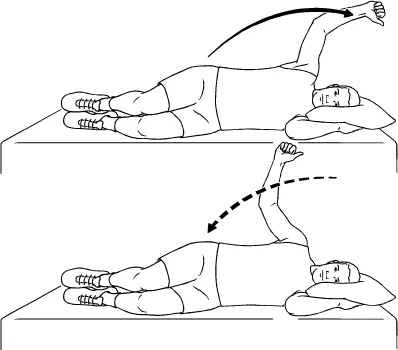

B) Side Lying Abduction (Short Lever)

- To perform this exercise, place the affected arm on top of your healthy side while lying down. As you raise your hand up to your chest, bend your elbow as much as you can.

- Raise your elbow away from your body and out to the side. Make an effort to point your elbow upward.

- Then go back to where you were before. Try to perform this for a total of five minutes, or until you become too tired to continue.

- For this workout, it is advised to attempt five sets of sixty seconds.

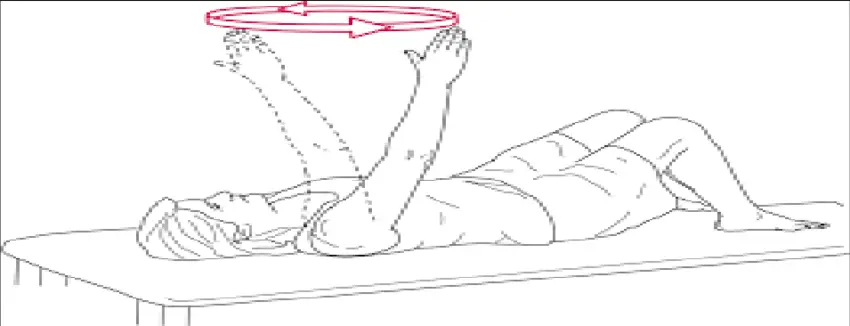

C) Circles (Short Lever)

- To perform this exercise, lie on your back and place a rolled towel under the elbow of the arm that is painful. Extend your elbow as much as possible.

- Your elbow should point straight up toward the ceiling as you shift your shoulder. To assist in lifting your hurting arm, you can utilize the other arm.

- When lifting the hurting arm, try to make sure your shoulder muscles are doing the majority of the effort if you are having trouble.

- Try using your elbow to create circles while pointing it toward the ceiling.

- Until you are completely exhausted and unable to perform anymore, aim for a total of five minutes.

- Try to complete five sets of sixty seconds in a clockwise direction, followed by five sets of sixty

D) Air Punches (Short Lever)

- To perform this exercise, place a rolled towel under the elbow of the arm that pains as you lie on your back.

- Your elbow should be 90 degrees bent. Punch straight up in the air, hold it for three seconds, and then carefully and slowly bring it back down to the beginning position.

- Aim for a total of five minutes, or until you are completely exhausted and unable to perform anymore.

- For this workout, it is advised to attempt five sets of sixty seconds.

- As you gain strength, you can increase the resistance and force your shoulder muscles to work harder by adding a tiny hand weight.

Level 3: Long Lever Exercises in Lying

A) Static 90 Degree Arm Hold

- Lay on your back to perform this exercise. Hold your arm straight and raise it to about a ninety-degree angle.

- If you are having a problem lifting your painful arm, you can try using your other arm to assist but try to ensure that your shoulder muscles are making the most of the effort when

- lifting the painful arm.

- Keep yourself in this posture for a total of five minutes, or until you are too tired to continue.

- For this exercise, five sets of sixty seconds are advised.

B) Circles (Long Lever)

- To complete this task: Place yourself on your back. Raise your arm to about ninety degrees, but keep it straight.

- If you are having problems lifting your painful arm, you can try using your other arm to assist but try to ensure that your shoulder muscles are doing the most of the effort when lifting the painful arm. With your fingers pointing straight up at the ceiling,

- maintain a straight arm. Refrain from adjusting the wrist. For five minutes in total, or until you are so exhausted that you are unable to perform anymore,

- move your shoulder in a clockwise circle. Consider attempting five 60-second sets instead.

- Next, rotate your shoulder anticlockwise for a total of five minutes, or until you are no longer able to do so due to tiredness. Or attempt five 60-second sets.

- Start increasing the size of the circular movement you perform as you gain strength. To make the shoulder muscles work harder, you can also progress by adding a small hand weight.

C) Crosses (Long Lever)

- Lay on your back to perform this exercise. Raise your painful arm to a ninety-degree angle.

- If you are having trouble lifting your painful arm, you can try using your other arm to assist but try to ensure that your shoulder muscles are doing the most of

- the effort when lifting the painful arm.

- Move your arm up and down in alignment with your body to begin. Repeat for a total of five minutes, or until you get too tired to continue. Or try five sixty-second sets.

- Next, extend the arm to the side and then return it, crossing the midline in the process.

- Five minutes in total, or until you become too tired to continue. Alternatively, attempt five 60-second sets.

- When you gain strength, you can work your shoulder muscles harder by increasing the resistance by constructing bigger As you gain strength,

- you can work your shoulder muscles harder by making larger crosses and adding a hand weight to increase resistance.

D) Long Lever Active Shoulder Flexion/Extension Pulses

- To do this exercise: Lie on your back. Lift your arm to 90 degrees. To assist in lifting your hurting arm, you can utilize the other arm.

- Keep your arm straight and move your arm back towards your head and then try to lower back to the bed (but don’t go all the way down) and then pulse this motion for 5 minutes in total or until you reach your fatigue point and are unable to do anymore.

- Do 5 sets of 60 seconds.

- Alternatively, to increase the workload on the shoulder muscles, add a hand weight.

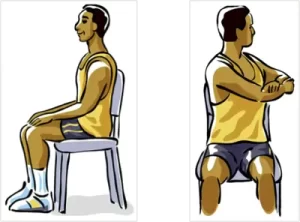

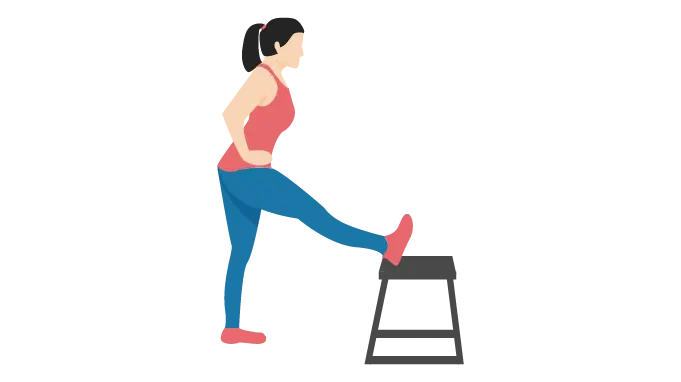

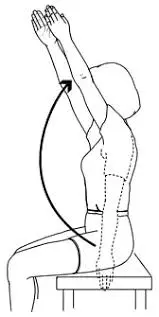

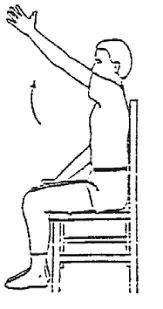

Level 4: Supported Sitting Short Lever Flexion

A) Short Lever Flexion (Supported Sitting)

- To perform this exercise: Sit with your back to the pillows, leaning backward while maintaining your posture.

- Try bending the elbow of the arm that pains as much as you can. Raise your elbow to the ceiling and then slowly lower yourself back to the beginning position.

- Aim for 5 minutes in total or until you feel fatigued and unable to do any more.

- You can try 5 sets of 60 seconds.

B) Short Lever Abduction (Supported Sitting)

- To do this exercise: Position yourself sitting up but leaning backward and supported by pillows.

- Extend the elbow of your arm that pains as much as you can. Raise, extend, and release your elbow from your body.

- Make an effort to point your elbow upward.

- Until you are completely exhausted and unable to perform anymore, aim for a total of five minutes.

- It is suggested to try to do 5 sets of 60 seconds.

Level 5: Supported Sitting Long Lever

(A) Active Shoulder Flexion/Extension Pulses

- To complete this exercise, sit up, lean back, and use cushions to support oneself.

- Raise your arm to shoulder height while maintaining a straight arm. If you are having trouble lifting your affected arm, you can use the other arm to assist, but be sure your shoulder muscles are strong enough.

- when lifting the sore arm, put forth the majority of the effort.

- Next, extend your arm as far as possible in the direction of your head, and then return it to your side (without going all the way down).

- Pulse for a total of five minutes, or until you are no longer able to do so due to weariness.

- It is advised to attempt five sets of sixty seconds.

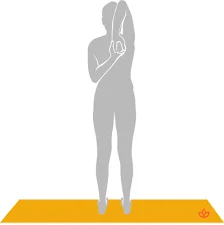

Stretches for deltoid pain

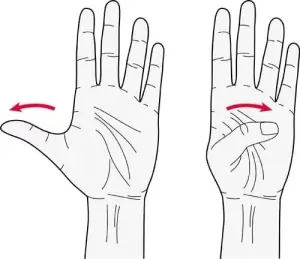

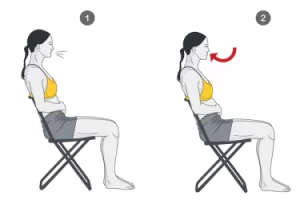

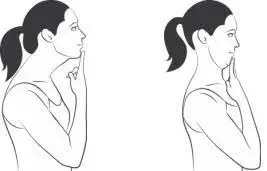

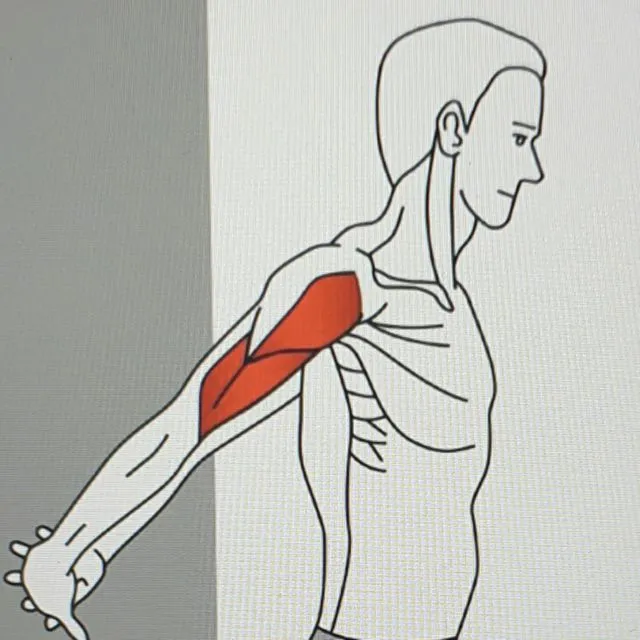

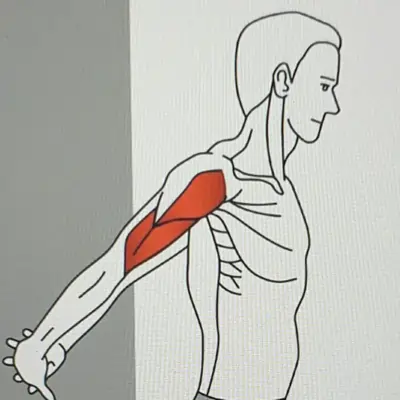

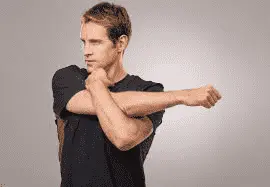

Anterior Deltoid Stretch

Sit or stand straight with the shoulder relaxed.

- As though you’re standing in an attentive position, clasp your hands behind your back.

- try holding one hand with the other or a used towel behind your back in two hands.

- Gently roll your shoulders, puff out the chest, and squeeze your shoulder blades together.

- Gradually pull your hands above where you feel a minor stretch or a pleasant discomfort.

- Make careful to keep your posture upright and avoid bending forward when doing this.

- Relax your body, breathe deeply via your nose, and hold this position for 15-20 seconds.

- Repeat 3-5 times as per required.

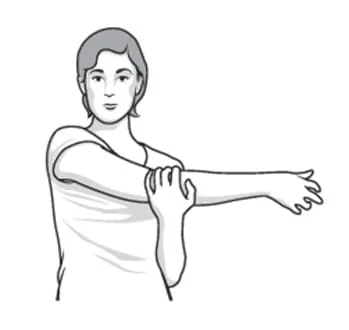

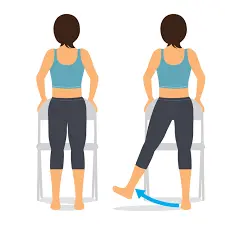

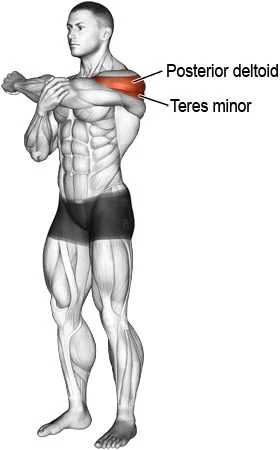

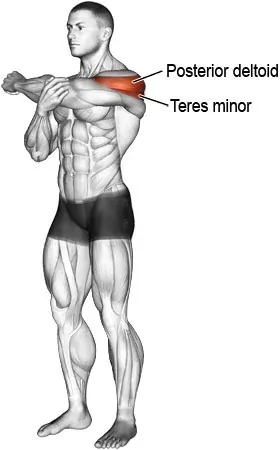

Posterior deltoid Stretch

- Sit comfortably on a chair or stool. As an alternative, take a relaxed stance with your feet somewhat wider than your hips.

- Stretch your arm sideways as though you passed a football to someone on the opposite side of you while maintaining a relaxed body posture.

- The second arm should be used to gently pull the extending hand’s elbow in the same direction.

- Make sure you are only pulling your outstretched hand and not leaning towards the same side.

- Pull till you feel a slight deep stretch.

- Maintain that for 15-20 seconds.

- Repeat 3-5 times.

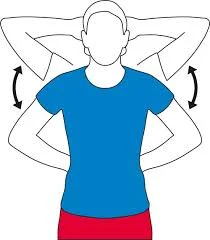

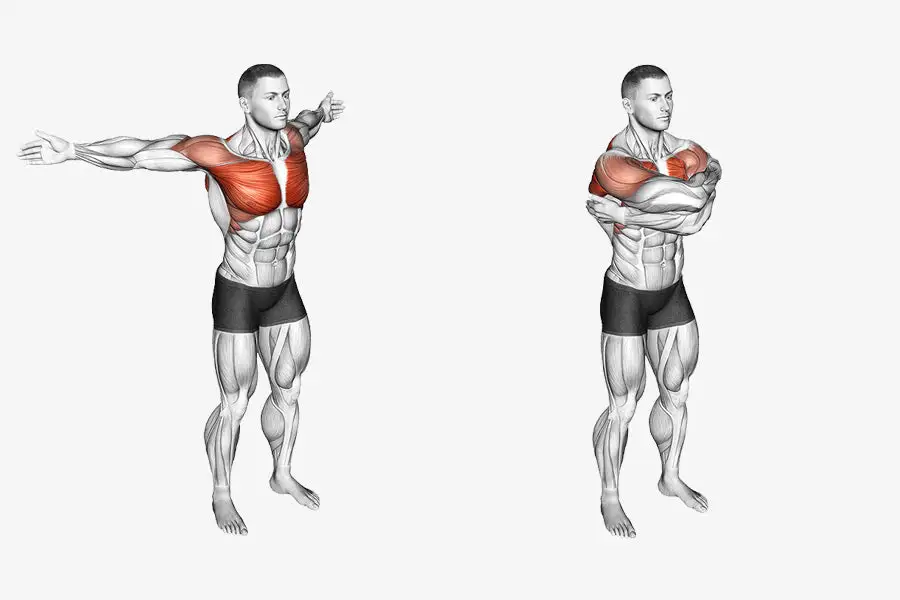

Dynamic Bear Hug Stretch

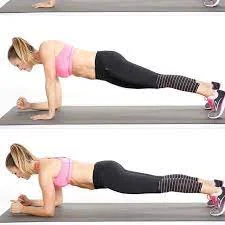

- The affected individual is in Place your feet shoulder-width apart and stand tall, maintaining a straight posture and tight core.

- Then, spread your arms wide as if you were going to give someone a hug.

- When the patient feels a light stretch across the front of the shoulder joint & chest, bring the arms across the chest,

- then hug by the patient’s self-right arm on the top of the left, till the patient feels a stretch at the back of the shoulder joint.

- Swing the arms out wide once more in a controlled motion.

- After reaching the limit of your range of motion, or ROM, swing your arms back into an embrace, placing your left arm on top of your right this time.

- For thirty seconds, this stretching is continued.

Do the Rest after that, then carry out the last two rounds.

Standing chest and shoulder stretch

- The patient is standing tall with the feet roughly hip-distance apart so that engaged core muscle & shoulder joint back.

- Must be focused on maintaining good posture.

- Then Reach behind the back with both arms & clasp the hands together.

- Take a breath in & as you exhale, lift the hands behind to as high as comfortably till they feel a good stretch across the front of the shoulders & chest. Hold the stretching position & breathe deeply for 30 seconds.

- Then Release & repeat two more times.

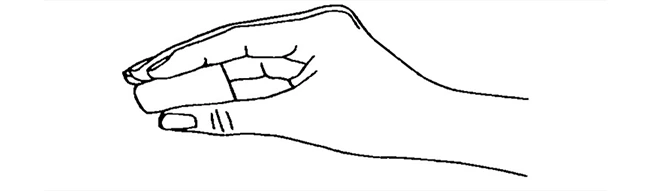

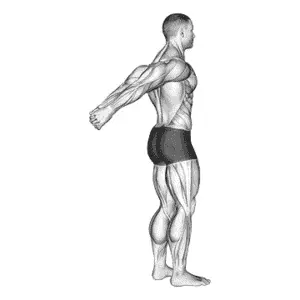

Cross-body shoulder stretch

- The patient is Standing position in tall with the feet hip distance apart & the muscle of the core is tight.

- To maintain proper posture, place your ears over your shoulders, hips, knees, and ankle joints.

- Bring your left arm across the body at shoulder height.

- Use the right hand to grab the left forearm.

- Gently pull the left arm closer to the body till the patient feels a stretch toward the middle of the left shoulder.

- Hold the stretching position & breathe deeply, for the30 seconds.

- Then take a break, and then perform this exercise twice more in front of the tricking sides.

Strengthening exercises for deltoid pain

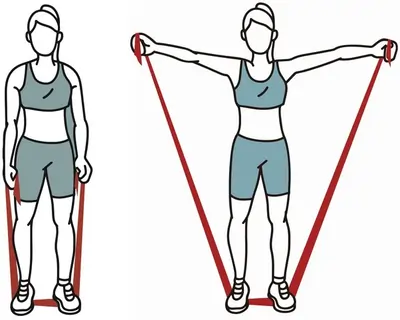

Since resistance band exercises allow the user to adjust the amount of resistance to bear, they are occasionally referred to as weighted exercises.

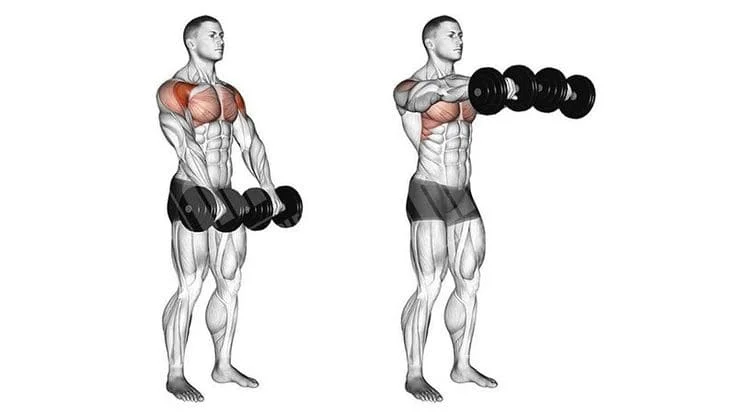

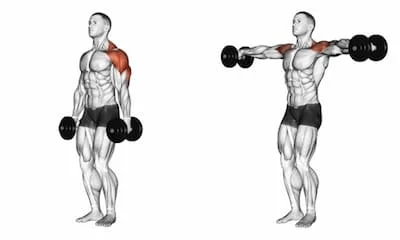

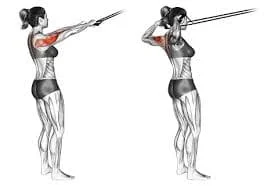

A) Rear deltoid Fly

- To do this exercise, place the middle of the resistance band beneath your feet as indicated in the above diagram, holding both ends of the theraband in your hands.

- After connecting the resistance band, raise your arms to shoulder height by gradually lifting them sideways.

- You can hold this position for 3-5 seconds or lower it immediately.

- One hand can be used to complete the movement first, or both hands can be used in sequence. One more hand is slowly left hanging on the side in the event that it happens later.

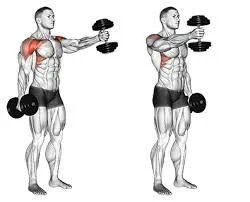

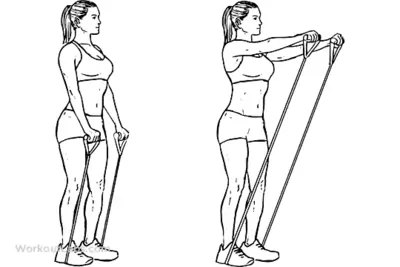

B) Front deltoid Raise

- To perform the movement, hold the resistance band’s edge in one hand and secure the other either underneath the foot or on one sturdy surface that is below your knee height, like the leg of the bed.

- Gently raise the arm in front of you.

- Either maintain the posture or quickly drop it.

- The movement should be pain-free and smooth.

- You can start off with 10-15 repetitions.

- Please remember to keep your elbows and knees relaxed or unlocked to prevent putting undue strain on your joints.

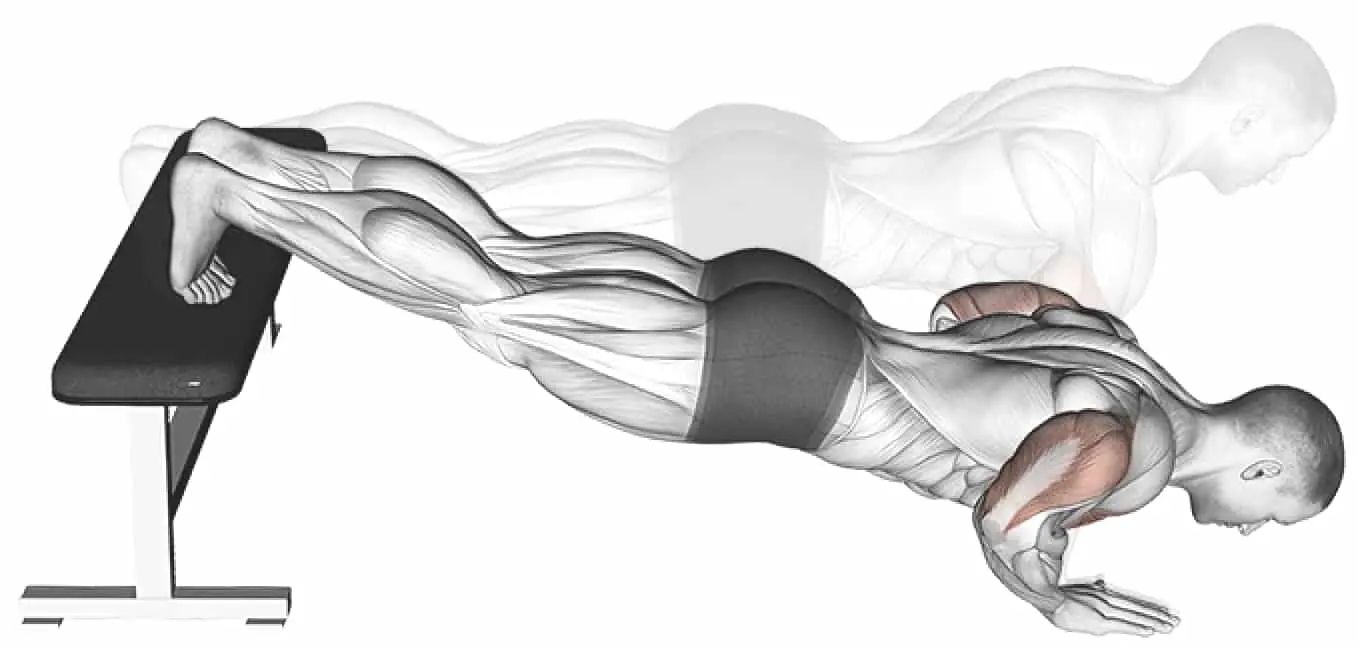

C) Reverse fly

- Hold a dumbbell in each hand while standing with your feet hip-distance apart. Lean your body forward diagonally and reach your arms toward the floor as you swing forward at the hips. Stretch your arms to the sides to the height of your shoulders.

- Put your shoulder blades together, then let go to return to the starting posture. Do this ten times over.

D)Dumbbell shoulder press

- Place your feet hip-distance apart as you stand. Raise a dumbbell with both hands. Raise the dumbbells until your arms are shoulder height, palms facing away from you, like a goal post. This is where you are supposed to start.

- Using your core to maintain stability on each repetition, push the dumbbells upward. Return to the starting position slowly. Ten repetitions should be made.

How to prevent deltoid muscle pain?

some prevention tips are given here

- Always do the Warm-up before the exercise and add a cool-down period after exercises

- Do the Stretch daily to improve the range of motion = ROM & flexibility

- Do the Rest after some exercise.

- If the patient works at a computer, make sure the keyboard is positioned so that positioned on the shoulder joint

- Don t overuse

- Always do Practice for good posture.

- If you have a physically demanding occupation, regular exercise can help to prevent injuries.

Follow a healthy diet and an exercise program to maintain a healthy lifestyle.

Conditions and Disorders

What conditions and disorders affect deltoid muscles?

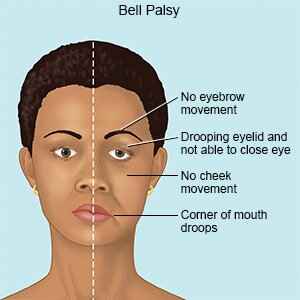

Axillary nerve palsy: Using crutches improperly, suffering a major injury, or having surgery can all cause nerve compression or damage. These issues might cause numbness or weakness in your shoulders, especially in the deltoid muscle.

Adhesive capsulitis: The thickening and stiffening of the capsule surrounding your shoulder joint causes this ailment. It may result in stiffness, muscle spasms, and shoulder pain.

Rotator cuff tears: Rarely does a serious rotator cuff injury cause the deltoid muscle to be damaged or dislocated.

Strains and overuse injuries: Overstretched muscle fibers might cause a shoulder strain. Strains may occur quickly or may build gradually over time as a result of repeated overhead arm motions.

Tendonitis: When your shoulder tendons become inflamed, you can get shoulder tendonitis. Tendonitis can impair your ability to move the joint, use your shoulder muscles, or produce deltoid pain.

FAQs

Does massage help deltoid pain?

For a number of conditions, massage is a highly helpful form of pain management. Massage therapy is a common and highly effective treatment for musculoskeletal neck and shoulder discomfort. Long-hold static stretches and deep tissue massages are effective ways to “relax” muscles.

Can deltoid muscle heal?

it depends on the severity of the deltoid muscle tear, and if surgery is required, it can take weeks to months to heal.

How should I sleep with deltoid pain?

Try sleeping on your back or the side that is not affected if you have a frozen shoulder. To ease some of the discomfort, place some pillows beneath the afflicted arm. To alleviate some of the related pain, you can also take some painkillers approximately one hour prior to going to bed.

Which exercise is best for shoulder pain?

Pendulum. Lean over and use a table or chair to support your non-injured arm while you begin the pendulum exercise.

Arm Extended Over Chest and then hold your right hand in front of you, keeping it close to your waist, to perform this stretch.

Is physiotherapy good for shoulder pain?

Physiotherapy is helpful in both treating and preventing shoulder problems that are related to sports. Your physiotherapist will perform a comprehensive examination to detect any weak points or abnormalities in your muscles.

References

- Garewal, D. (2021, January 3). Deltoid Pain: A Simple Guide to Muscle Pain & Relief. Melbourne Arm Clinic. https://melbournearmclinic.com.au/deltoid-pain/

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Deltoid Muscles. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21875-deltoid-muscles

- Walden, M. (2022, October 6). Deltoid Pain. Sportsinjuryclinic.net. https://www.sportsinjuryclinic.net/acute-shoulder-injuries/deltoid-muscle-strain

- Patient, R. M. (n.d.). Deltoid | Rehab My Patient. https://www.rehabmypatient.com/shoulder/deltoid

- Deltoid Muscle Pain – Causes & Best Treatment Options in 2024. (2024, March 23). ProHealth Prolotherapy Clinic. https://prohealthclinic.co.uk/blog/deltoid-muscle-pain/

- Deltoid Muscle Pain – Causes & Best Treatment Options in 2024. (2024, March 23). ProHealth Prolotherapy Clinic. https://prohealthclinic.co.uk/blog/deltoid-muscle-pain/

- Deltoid Rehab Program | ShoulderDoc. (n.d.). https://www.shoulderdoc.co.uk/article/1028

- Cronkleton, E. (2023, February 3). Top 10 Exercises to Relieve Shoulder Pain and Tightness. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/shoulder-pain-exercises

- Deltoid. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Deltoid

- Eight Stretches You Need to Strengthen & Mobilize Your Shoulders. (n.d.). DMoose. https://www.dmoose.com/blogs/training/8-stretches-tone-strengthen-shoulders

- https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/recovery/shoulder-surgery-exercise-guide/