Scapula Bone

Introduction

The triangular, flat scapula bone is referred to as the “shoulder blade”. It is located in the upper thoracic region on the posterior part of the rib cage. It connects the humerus at the glenohumeral joint and the clavicle at the acromioclavicular joint to form the shoulder joint. The scapula is attached to 17 separate muscles in total, which causes fractures of the scapula bone in rare cases.

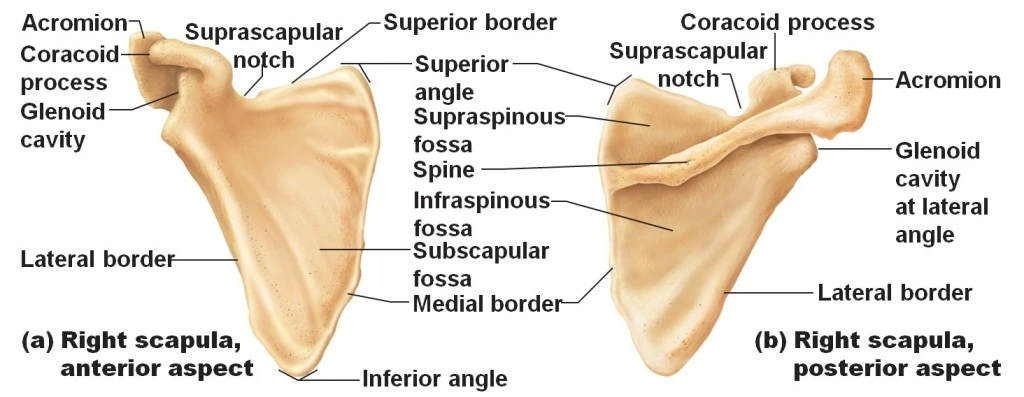

Side determination of the Scapula Bone

The glenoid cavity is received by the large glenoid curve, which is lateral to the body.

The indented character should be directed ventrally, and the convex character with the spinous process should be oriented dorsally.

The triangular spine separates the convex dorsal feature into the supraspinatus and infraspinatus fosses.

The thickest structure on the side runs from the inferior angle descending to the glenoid cavity above.

Structure and function of the scapula bone

Structure of the Scapula Bone

The scapula contains several processes, projections, and attachment surfaces and serves as a location of attachment for numerous muscles. The scapula has two surfaces (ventral and dorsal), three boundaries (medial, lateral/axillary, and superior), and three angles (superior/medial, lateral, and inferior). The acromion, spine, and coracoid process are the three processes that make up the scapula. The “Muscles” section discusses how muscles are attached to these landmarks.

The subscapularis joins to the vast concavity known as the subscapular fossa on the ventral surface of the scapula, which borders the thoracic rib cage. This fossa has three ridges that facilitate tendinous adhesion. The scapular spine, which emerges from the posterior scapula and separates into two uneven portions before creating the acromion, divides the dorsal surface.

A ridge extends from the glenoid cavity to just above the inferior angle along the infraspinatus fossa close to the lateral boundary. The infraspinatus muscle and the teres major and minor muscles are divided by this ridge.

The Suprascapular nerve and artery pass via the spinoglenoid notch, which joins the two fossae. These are located beneath the acromion and serve the infraspinatus muscle. The acromion, which is the palpably highest point of the shoulder, is an oblong extension of the spine that extends laterally and then anteriorly above the supraspinous fossa. From the superior angle to the coracoid process, the scapula’s superior border is located. The lateral superior aspect of the ventral surface gives rise anteriorly to the hook-shaped coracoid process.

It serves as a site of attachment for muscles and ligaments, the same as the acromion.

There is a notch at the base of the coracoid, and the superior transverse scapular ligament closes it up, creating a foramen. This foramen is used by the Suprascapular nerve, and the Suprascapular artery passes directly above the ligament. The glenoid cavity, where the humeral head articulates with the scapula, is located at the lateral angle of the scapula. The glenoid labrum, a fibrocartilage nous tissue, deepens the cavity at its edges to accept more of the humeral head.

The long head of the triceps brachia starts at an imprint known as the infraglenoid tuberosity, which is located directly beneath the hollow. The tendons of the two sites at which scapular ligaments attach are mostly used to name them. These include the glenohumeral ligaments, acromioclavicular ligament, coracoacromial ligament, coracoclavicular ligament, coracohumeral ligament, and transverse scapular ligament (which was previously mentioned).

The function of the Scapula Bone

Six movements are possible for the scapula thanks to the muscles that link to it:

- Elevation: The scapula is elevated by the Levator scapulae and upper trapezius.

- Depression: Scapula is brought down by the lower trapezius.

- Upward rotation: During upper extremity abduction, the scapula is rotated by the upper and middle trapezius.

- Downward rotation: The rhomboids achieve this by extending behind the back and downward.

- Retraction (adduction): During rowing actions, the rhomboids and middle trapezius contract, separating the scapula from the thoracic wall.

- Protraction, or abduction: it occurs when the serratus anterior contracts, pressing the scapula up against the thoracic wall.

Embryology of the Scapula Bone

The scapula derives from the embryologic mesoderm, just like other bones. Week 11 of human embryogenesis is when its osteogenic development begins.

Scapula bone in other animals

Fish have a structure called the scapular blade that is fixed to the top surface of the pectoral fin articulation. On the bottom surface of the fin is a structure called the coracoid plate. While both plates are typically modest in most other fish and may be partially cartilaginous or composed of various bony parts, they are robust in cartilaginous fish.

These two structures developed into the scapula and a bone known as the precoracoid, which is also called the “coracoid” but is not related to the named mammalian structure, respectively, in the early tetrapods.

These two bones are separate in reptiles and amphibians (including birds), but they combine to form a single structure that houses many of the forelimb’s muscle attachments. The scapula in these species is typically a simple plat. Still, there are significant differences in the fine structure of these bones among living cultures.

Turtles’ joined precoracoid bones form a Y-shape to allow the scapula to stay attached to the clavicle, which is part of the shell, but frogs may brace their precoracoid bones together at the underside of the animal to absorb the shock of landing. The precoracoid in birds aids in supporting the wing against the sternum’s upper surface.

The real coracoid, the third bone in therapist fossils, developed immediately behind the precoracoid. The precoracoid has been removed from all other living mammals, and the coracoid bone has fused with the scapula to form the coracoid process. The resulting three-boned structure is still present in current monotremes.

The muscles that were formerly connected to the precoracoid are no longer needed, which is connected to mammals’ upright walk as opposed to reptiles’ and amphibians’ more widespread limb arrangement. The rest of the scapula has also changed in shape due to the changing musculature; the old bone’s anterior margin became the spine and acromion, from which the major shelf of the shoulder blade emerges as a new structure.

The coracoid and scapula, or shoulder blade, were the two primary pectoral girdle bones in dinosaurs, and they both articulated with the clavicle directly. While it was mostly lacking in ornithischian dinosaurs, the clavicle was present in saurischian dinosaurs. The location on the scapula where the humerus and it articulated is called the humerus.

Lymphatics and Blood Supply of the Scapula Bone

The thyrocervical trunk, a branch of the subclavian artery, and the axilla artery, which is the subclavian artery’s continuation beyond the lateral margin of the first rib, are the sources of the anastomosis that give blood to the posterior aspect of the scapula.

Blood Supply of the scapula bone

Branches of the thyrocervical trunk

The transverse cervical artery follows the scapula’s medial edge. May give rise to a branch known as the dorsal scapular artery, which is deep and descending. The subclavian artery is where this artery most frequently splits off.

The supply of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles is the Suprascapular artery.

Branches of the subclavian arteries

Subscapular artery: Supplies blood to the subscapularis muscle up to the scapula’s inferior angle.

A branch of the subscapular artery is the circumflex scapular artery. forms an anastomosis between the transverse cervical artery’s deep branch and the Suprascapular artery.

Drainage of the scapular veins: mostly through the Suprascapular and axillary veins

Lymphatics of the scapula bone

Drainage of lymph is as follows

Right lymphatic duct – Right scapula bone

Thoracic duct: left scapula bone

The supraclavicular and axillary lymph nodes These two lymph nodes are related to the scapula.

Muscle Attachment of the Scapula Bone

The intrinsic muscles of the scapula stick straight to the surface of the bone. The four muscles that make up the rotator cuff function to the glenohumeral joint stabilized. Among them are:

Intrinsic scapular muscles

- Origin: supraspinatus Fossa

- Insertion: At the top of the larger tubercle.

- Nerve supply: Suprascapular nerve innervation (C5, C6).

Infraspinatus

- Origin: Infraspinatus fossa is the origin. ‘

- Insertion: There is a minor insertion between the supraspinatus and the greater tubercle of the humerus

- Nerve supply: Suprascapular nerve innervation (C5, C6).

Teres minor

- Origin: The lateral/axillary border and the posterior side of the scapula are adjacent.

- Insertion: The inferior side of the greater tubercle on the humerus.

- Nerve supply: Axillary nerve innervation (C5, C6).

Subscapularis

- Origin: subscapular fossa.

- Insertion: Humeral tubercle

- Nerve supply: Subscapular nerves (C5, C6, C7) are innervated.

Extrinsic scapular muscle

Extrinsic scapular muscles are attached to the processes of the scapula and influence glenohumeral joint motion: Among them are as below

Biceps Brachii

- Origin: Coracoid process with a short head, Long head: tubercle supraglenoid.

- Insertion: Forearm fascia and radial tuberosity

- Nerve supply: Musculocutaneous nerve (C5, C6) innervation.

- Origin: Medial head: below the radial groove, Lateral head: above it Long head: scapula’s infra glenoid tubercle.

- Insertion: Forearm fascia and ulnar olecranon process.

- Nerve supply: Radial nerve innervation (C6, C7, C8).

Deltoid

- Origin: Acromion, scapular spine, and lateral clavicle.

- Insertion: Tuberosity of the Deltoid.

- Nerve supply: Axillary nerve innervation (C5, C6)

Stabilizing scapular muscle

The following are scapular stabilizing muscles:

Trapezius

- Origin: Skull, spinous processes of C7 to T12, and nuchal ligament

- Insertion: scapular spine, acromion, and clavicle.

- Nerve supply: Levator scapulae Accessory nerve (Cranial nerve XI)

Levator Scapula

- Origin: C1–C4 vertebral transverse processes.

- Insertion: Scapula’s medial border.

- Nerve supply: C3, C4, and the dorsal scapular nerve (C5) are innervated

Serratus anterior

- Origin: the side of the chest where the top eight ribs are located.

- Insertion: Throughout the whole anterior length of the scapula’s medial edge.

- Nerve supply: Long thoracic nerve innervation (C5, C6, C7).

Rhomboid major

- Origin: T2 through T5 vertebral spinous processes.

- Insertion: Scapula’s inferomedial boundary.

- Nerve supply: Dorsal scapular nerve (C5) innervation.

Rhomboid minor

- Origin: C7 to T1 vertebrae’s spinous processes.

- Insertion: Scapula’s medial border.

- Nerve supply: Dorsal scapular nerve (C5) innervation.

Additional scapula-attached muscles include:

Latissimus dorsi

- Origin: The iliac crest, inferior three ribs, spinous processes of T6 to T12, inferior angle of the scapula, and Thoracolumbar fascia.

- Insertion: The humerus’s intertubercular sulcus.

- Nerve supply: Thoracodorsal nerve innervation (C6, C7, C8).

Teres Major

- Origin: the inferior angle of the scapula’s posterior surface.

- Insertion: The medial portion of the intertubercular groove.

- Nerve supply: Lower scapular nerve innervation (C5, C6).

Pectorals Minor

- Origin: Near their respective costal margins, the third, fourth, and fifth ribs

- Insertion: The coracoid mechanism,

- Nerve supply: Medial pectoral nerve innervation (C8, T1).

Coracobrachialis

- Origin: Process of coracoid.

- Insertion: On the medial aspect of the middle of the humerus.

- Nerve supply: Musculocutaneous nerve (C5, C6, C7) innervation.

Omohyoid

- Origin: Scapula’s superior boundary.

- Insertion: Hyoid’s inferior edge.

- Nerve supply: cervical ansa (C1, C2, C3).

Ligaments attached to the scapula

The boundary of the glenoid cavity is where the glenoid labrum and the shoulder joint capsule are joined.

Attached to the margin of the facet on the medial aspect of the acromion is the acromioclavicular joint capsule. The coracoacromial ligament is linked to the medial side of the acromion process tip and the lateral border of the coracoid process.

The coracohumeral ligament is linked to the coracoid process at its root.

The attachment points of the coracoclavicular ligament are the conoid part near the root of the coracoid process and the trapezoid portion on the superior aspect.

The coracoclavicular ligament is composed of the conoid and trapezoid bands, which both provide vertical support. The coracoid and coracoacromial ligament are connected.

The Suprascapular ligament, which crosses the Suprascapular notch, forms a foramen through which the Suprascapular nerve is conveyed. The suprascapular ligament is located above the ligament.

The spinoglenoid ligament passes over the spinoglenoid notch. The suprascapular vessels and nerves supply it.

Horizontal support is provided by the acromioclavicular ligament, which joins the acromion to the distal end of the clavicle.

Bursa around the scapula bone

Two main bursas exist:

The subscapularis bursa is located between the subscapularis and the serratus, while the Scapulothoracic bursa is situated between the thorax and the serratus.

Biomechanics of the scapula bone

During functional elevation, the scapula moves posteriorly in the parasagittal plane, rotates externally in the transverse plane, and rotates upward in the frontal plane. Scapular control is required for the proper operation of scapulohumeral coordination. Posterior tilting causes the humeral clearing that takes place during the acromiohumeral phase of shoulder elevation.

The only joint that joins the scapula to the upper limb is the acromioclavicular joint. It makes contact with the back of the chest wall. The acromioclavicular joint moves independently, and the scapulothoracic joint is the sole joint that moves in conjunction with it.

The scapulothoracic joint cannot move without the acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints. To accomplish total arm elevation, the scapula, clavicle, and humerus cooperate in the 2:1 scapulohumeral rhythm.

This suggests that every two degrees is moved at the humerus for every two degrees at the scapula. The arm can be raised 180 degrees overall thanks to the 120-degree range of motion in the glenohumeral joint and the 60-degree upward rotation in the scapulothoracic joint. While the scapula needs to rotate externally, tilt posteriorly, and rotate upward, the clavicle needs to elevate, retract, and roll posteriorly.

Extension of the thoracic spine is necessary. The muscles that cooperate to enable upward rotation are the serratus anterior and the upper and lower trapezius.

A study found that scapular upward rotation and retraction are larger with abduction elevation than with flexion elevation. They also discovered that posterior tilting peaked during flexion elevation. Scapulothoracic movement can be reduced by any disruption in this rhythm, which can involve tiredness, a decrease in range of motion.

Anatomical Variantions Of the Scapula

Os acromial

Tenderness and soreness may be experienced due to the unfused center of secondary ossification in the acromion. It is believed to raise the possibility of rotator cuff tears and impingement. In situations that are not responding to conservative treatment, surgical removal of the unfused fragment may be considered as a last resort.

Sprengel deformity of shoulder

Congenital elevation of the scapula resulting in reduced functionality of the scapula and upper limb is known as Sprengel deformity. The most common method for improving the scapula’s appearance and usefulness is surgical reconstruction. Although it is uncommon, this is the most prevalent scapula variation.

Clinical Importance of the Scapula Bone

Winging of Scapula

The serratus anterior, the main muscle responsible for pushing the scapula towards the rib cage, becomes paralyzed when an injury results in the denervation of the long thoracic nerve. The medial scapula retracts and the entire scapula is raised as a result of the reduced protraction that permits the rhomboid and trapezius muscles to contract without interference.

The outcome is a restriction in upper extremity functionality and medial winging of the scapula. Rarer still, palsy of the rhomboids or trapezius may result in lateral winging. By looking at the scapula, it is simple to diagnose serratus anterior palsy, and asking the patient to push against a wall will make their winging more noticeable. The pillars of treatment include physical therapy, activity moderation, and pain reduction. Treatment approaches are generally conservative. 25 percent of patients are candidates for surgical reconstruction after failing conservative therapy.

Scapulothoracic Crepitus

Scapulothoracic Crepitus (Snapping Scapula Syndrome)

This syndrome is characterized by audible and painful crepitus with a motion of the scapula caused by disruption of the anterior scapula’s gliding motion over the posterior thoracic cage (the Scapulothoracic joint). It has been proposed that bursitis, trauma, repetitive use, and osteophyte growth could be the causes of this condition.

Most of the time, conservative treatment is the first choice and has good outcomes. To treat this condition, physical therapy is used to widen the gap between the scapula and chest wall. NSAIDs or corticosteroid injections are also used to relieve pain. Resecting any lesions in the Scapulothoracic joint is the surgical treatment reserved for situations that do not respond well to other treatments.

Dissociation of Scapulothoracic joint

Traumatic injury disrupts the Scapulothoracic joint, which results in lateral displacement of the scapula and damage to blood vessels and nerves. This injury may result in life loss or limb loss, depending on the degree of vascular and brain damage.

During the examination, there may be upper extremity numbness, weakness, and pulselessness as well as shoulder enlargement. It is advisable to take radiographs. to ascertain whether the acromioclavicular or sternoclavicular joints are detached, or whether the clavicle or scapula are fractured. When a limb is in danger of becoming ischemic or there is active arterial bleeding, surgery is recommended.

To fix fractures and joint detachments, surgery is also necessary. Shoulder dystocia, an obstructive vaginal birth problem typically characterized by impaction of the anterior fetal shoulder against the maternal symphysis pubis, is the most common risk factor for neonatal brachial plexus palsy.

Teens with a history of shoulder pain may exhibit posterior-inferior glenoid dysplasia, characterized by a silent dislocation of the glenohumeral joint caused by the humeral head sliding posteriorly during internal rotation and elevation of the arm. On occasion, this is connected to a distinctive dimple on the back of the affected shoulder.

Scapula snapping syndrome

Many muscles reside between the ribs and the scapula to enable the scapula to slide easily over the chest wall (referred to as the scapulothoracic joint). Additionally present, bursae help to cushion the tissue and lessen friction.

The two primary bursae at the scapulothoracic joint are the subscapularis bursae (between the subscapularis muscle and serratus anterior muscle) and the scapulothoracic bursae (also called infraspinatus; between the serratus anterior muscle and chest wall).

An irregularity at the scapulothoracic joint that results in non-smooth articulation is known as snapping scapula syndrome. Lesions and scapulothoracic bursitis, an inflammation of the bursae, are the two most frequent causes. Osteochondroma is the most frequent cause of lesions; it is a benign benign cartilage tumor that may result in lesions on the scapula’s anterior surface. Overuse of the joint as a result of repeated arm motions over the head is the most frequent cause of scapulothoracic bursitis.

Fractures

Like any other bone, the scapula is prone to fractures. However, because the scapula is so well-protected, they only make up 0.5 to 1% of all fractures. The scapula is shielded from the anterior and posterior directions by the rib cage and thoracic cavity, respectively. It is also heavily covered in soft tissue or muscle.

Scapular fractures are therefore usually the result of high-impact direct trauma, and nearly all of these fractures are associated with additional very serious, occasionally numerous, and potentially fatal injuries. Scapular fractures are hence frequently misdiagnosed.

Scapular Dysplasia

Scapular dysplasia is an abnormal morphology of the scapula that can arise from intrinsic or acquired brachial plexus palsy during pregnancy. The scapula can be thought of as a modular component that comes from many ossification locations, including the spine/acromion block, glenoid/coracoid block, and blade. Insufficient glenoid ossification causes bilateral anatomical changes in primary dysplasia.

This results in degenerative changes in older adults; in infants, it causes clicking, instability, or pain. Infants with brachial plexus injuries after delivery may also exhibit morphological alterations in their scapula as a result of aberrant development of the posterior glenoid cartilages.

Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy

The face, humerus, and scapula muscles are first affected by this autosomal dominant muscular dystrophy syndrome, which then progresses to the muscles of the trunk and lower extremities. The goal of slowly increasing physical treatment is to strengthen the muscles without endangering them more. It has been demonstrated that shoulder function is improved in these patients after surgery to stabilize the scapula against the thoracic cage.

Rotator cuff tendonitis/impingement

The majority of the time, rotator cuff tendonitis/impingement is caused by the supraspinatus muscle tendon being squeezed down by the acromion, resulting in pain during overhead movements. Inflammation within the bursa that surrounds the tendon and around it may result from this disorder.

Surgical Importance

Because the glenoid fossa and labrum make up the scapular component of the shoulder joint, scapular surgical procedures are most frequently performed during shoulder arthroplasty. Shoulder osteoarthritis or inflammatory arthritis that is resistant to conservative treatment, as well as other proximal humeral or rotator cuff diseases, are indications for shoulder arthroplasty. Extra care should be used during shoulder arthroplasty to prevent harm to the axillary nerve.

Summary

On the posterolateral aspect of the thoracic cage is the scapula, or Latin shoulder blade. There are three boundaries, three angles, two surfaces, and three operations on the scapula.

Once more, the shoulder blade is referred to as the scapula. It articulates at the glenohumeral joint with the humerus and at the acromioclavicular joint with the clavicle. The thorax and upper limb are joined by the scapula. It is a flat, triangular bone that provides a point of attachment for numerous muscles. The scapula’s anatomy, including its articulations, bony landmarks, and clinical significance, is covered in this article.

FAQ

Where is the scapula bone attached?

Scapula bone is triangular in shape and is referred to as the “shoulder blade”. In the upper thoracic region, it is located on the dorsal surface of the rib cage. To form the shoulder joint, it joins the clavicle at the acromioclavicular joint and the humerus at the glenohumeral joint.

Which muscle keeps the scapula stable?

Serratus anterior

Which muscle raises the shoulder blades?

Levator scapula muscles

What is a scapula muscle weakness?

When the scapular muscles are too weak or paralyzed to stabilize the scapula, the condition is referred to as a “winged scapula” (also known as scapula alata).

What features make the scapula unique?

One bone that is crucial to the process of the shoulder joint is the scapula. It has six different types of motion, including protraction, retraction, elevation, depression, upward rotation, and downward rotation, that enable full functional movement of the upper extremities.

What causes discomfort in the scapula?

Scapular dyskinesis can be caused by weakening, imbalance, tightness, or, in rare cases, the detachment of the muscles that move the scapula. damage to the nerves that provide the muscles. damage to the scapular-supporting bones or injuries to the shoulder joint itself.

Which vessels supply blood to the scapula?

The subclavian artery and the axillary artery are two significant arteries that pass behind the clavicle and in front of the scapula.

Are the scapula bones flat?

The flat bone called your scapula is also known as your shoulder blade. In your upper back, there are two of these triangle-shaped bones. Your scapula is where the muscles that rotate your arms are attached.

Is there a spine on the scapula?

The spine of the scapula is a noticeable bone ridge located on the posterior surface of the scapula, also known as the shoulder blade. The superior supraspinous fossa and inferior infraspinous fossa are the two portions of the posterior surface of the scapula that are divided by this projection, which resembles a shelf.

What is the scapula’s neck?

The part that surrounds the head and is slightly constricted is called the neck of the scapula; it is more noticeable from below and behind than from above.

References

- TeachMeAnatomy. (2022, December 22). The Scapula – Surfaces – Fractures – Winging – TeachMeAnatomy. https://teachmeanatomy.info/ upper-limb/bones/scapula/

- Miniato, M. A. (2023, July 24). Anatomy, thorax, scapula. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbinlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538319/

- Scapula. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Scapula

- Wikipedia contributors. (2023a, October 21). Scapula. Wikipedia. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scapula***

- De Souza, P. (2021, December 14). Scapula. AnatomyZone. https://anatomyzone.com/upper-limb/pectoral-girdle-and-shoulder/scapula/

- Scapular dyskinesis. (n.d.). https://www.nationwidechildrens.org/ specialties/sports- medicine/sports-medicine-articles/scapular-dyskinesis

- Scapular (Shoulder Blade) Problems and Disorders – OrthoInfo – AAOS. (n.d.). https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases–conditions/scapular-shoulder-blade-disorders

- Rohit, B. (2023a, February 23). Scapula Bone – Surfaces, Attachments, Biomechanics – Samarpan. Samarpan Physiotherapy Clinic. https://samarpanphysioclinic.com/scapula-bone/#Introduction

- Smith, C. (n.d.). 3D skeletal system: the shoulder girdle. https://www.visiblebody.com/blog/3d-skeletal-system-the-shoulder-girdle

- Staff. (2022a, September 16). Scapula (Shoulder Blade) – Anatomy, Location, & Labeled Diagram. TheSkeletalSystem.net. https://www.theskeletalsystem.net/arm-bones/scapula.html

- Modric, J. (2017, June 9). Scapula (Shoulder Blade) Anatomy, muscles, Location, function – eHealthStar. eHealthStar – Evidence-Based Health Articles. https://www.ehealthstar.com/anatomy/shoulder-blade-scapula

13 Comments