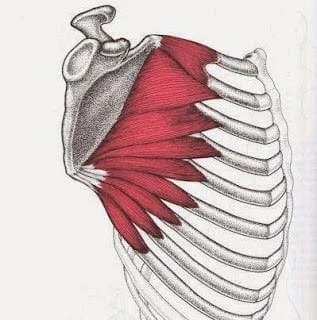

Serratus Anterior Muscle

The serratus anterior muscle is a crucial anatomical structure located on the lateral aspect of the rib cage, extending from the first to ninth ribs. Often referred to as the “boxer’s muscle” due to its prominence in fighters, this muscle plays a vital role in various arm and shoulder movements, contributing significantly to upper body stability and mobility.

What is the Serratus Anterior Muscle?

The fan-shaped serratus anterior muscle inserts along the scapula’s superior angle, medial border, and inferior angle. It starts on the superolateral surfaces of the first through eighth or the first to ninth ribs at the lateral wall of the thorax. The serratus anterior’s primary portion can be felt between the latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major muscles, deep to the scapula and pectoral muscles.

The serratus anterior superior, which inserts close to the superior angle, the serratus anterior intermediate, which inserts along the medial border, and the serratus anterior inferior, which inserts close to the inferior angle, are the three main divisions of this large muscle.

Structure Of Serratus Anterior Muscle

Anteversion and protraction of the arm are made possible by the serratus anterior muscle, which pushes the scapula around the thorax. When the serratus anterior superior and serratus anterior inferior work together, this motion is opposed to that of the rhomboid; however, the scapula is then forced on the thorax in concert with the rhomboids, producing a synergistic effect.

Additionally, the anterolateral scapular motion—which permits arm elevation—is a function of the serratus anterior inferior. All three components of the serratus anterior muscle cooperate to raise the ribs and aid in breathing when the shoulder girdle is stabilized.

Function Of Serratus Anterior Muscle

The protraction of the scapula, which happens when delivering a punch, is mostly caused by the serratus anterior, popularly referred to as the “boxer’s muscle.” Moreover, the serratus anterior collaborates with the lower and upper trapezius muscle fibers to maintain the scapula’s upward rotation, enabling overhead lifting.

All three of the previously mentioned elements pull the scapula forward around the thorax, which is necessary for the arm to be elevated. As a result, the muscle opposes the rhomboids. The scapula is pressed on the thorax together with the rhomboid when the inferior and superior parts work in unison, though, and for this reason, these parts also work in concert with the rhomboids. Elevating the arm is made feasible by rotating the scapula by pulling its lower end laterally and forward with the inferior part. Furthermore, with the shoulder girdle fixed, all three components can raise the ribs, aiding in breathing.

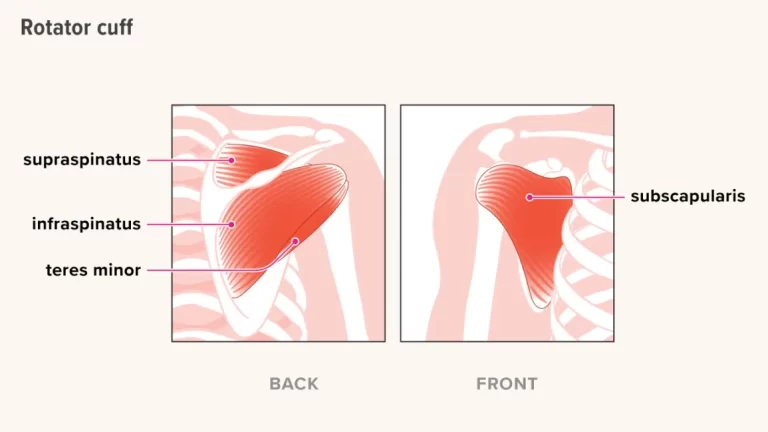

Relations

The subscapularis (supra serratus) bursa divides the deep-lying serratus anterior from the subscapularis. The infraspinatus burs (scapulothoracic) divides it from the rib.

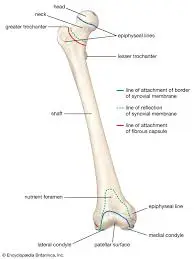

Origin

The upper lateral surface of the eight or nine upper ribs is where it starts. After that, it encircles the ribcage posteromedially, going under the scapula and inserting itself on the medial border of the underside of the scapula.

Tendinous septa separate the muscle as it emerges from the ribs into nine “digitations,” or finger-like clusters of muscle fibers. Between these septa, the fibers run obliquely (to differing degrees), creating a multipennate muscular architecture.

The lowest six digitations are referred to as inferior fibers, while the above three digitations as superior fibers. The fibers of the external oblique interdigitate with the lowest four digitations of the serratus anterior.

Insertion

It attaches to the scapula’s front edge. The muscle is divided into three sections:

- Upper / Superior: superior angle of scapula → 1st to 2nd rib.

- Middle/Intermedius: 2nd to 3rd rib → scapular medial boundary.

- Lower / Inferior: inferior angle of the scapula and medial border from the 4th to the 9th rib. It is the most significant and potent component.

Nerves Supply

The serratus anterior is innervated by the long thoracic nerve, which arises from the top part of the superior trunk of the brachial plexus and is usually made up of the cervical nerves C5, C6, and C7. Because it runs inferiorly along the serratus anterior, the long thoracic nerve is vulnerable to injury during some surgical operations, particularly when axillary lymph nodes are dissected.

Greater exposure occurs along the nerve’s course due to its superficial course over the surface of the serratus anterior muscle, less connective tissue, and relatively smaller diameter as compared to other brachial plexus nerves.

Other non-surgical causes of injury to the long thoracic nerve include traction on the nerve itself, entrapment inside the middle or posterior scalene muscles, and compression of the nerve by the second rib, fascial sheath, or middle scalene muscle.

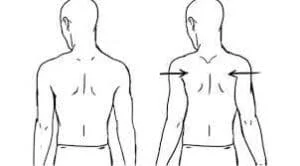

A winged scapula is a clinical condition that arises when the serratus anterior fails to maintain the scapula’s attachment to the chest wall due to injury to the long thoracic nerve. The winging is caused by a weakening in the rhomboids or the trapezius muscles, and it must be distinguished from lateral winging caused by the medial scapula.

Different parts of the serratus anterior have different innervations, which implies that the middle and inferior segments may be the real serratus anterior muscle, whereas the superior part may be closely connected to the levator scapulae. The long thoracic nerve and its independent branch, which is not connected to the main trunk, are the two sources of innervation of the superior portion. The independent branch shares a similar route with the neurons that innervate the levator scapulae muscle and is related to branches from C4, C5, or C6.

Regarding the middle segment of the serratus anterior, one-third of the anterior region, situated between the origin and insertion, is where the long thoracic nerve descends. Lastly, the inferior section is innervated by two sources, just like the superior segment: a branch of the intercostal nerve and the long thoracic nerve.

Artery Supply

- Lateral thoracic artery

- Superior thoracic artery

- Thoracodorsal artery

Blood Supply

The lateral thoracic artery, superior thoracic artery, and thoracodorsal artery provide blood flow to the serratus anterior. The axillary artery is the source of the lateral thoracic artery, commonly referred to as the external mammary artery. It flows along the pectoralis minor’s bottom edge, supplying the serratus anterior and pectoralis major muscles with oxygen-rich blood.

Lymphatics

Branches reach the subscapularis muscle and axillary lymph nodes by crossing the axilla. Although it might originate from the thoracoacromial artery, the upper thoracic artery is normally the first division of the axillary artery.

The superior thoracic wall supplies the first and second intercostal gaps and the superior part of the serratus anterior.

The thoracodorsal artery supplies the latissimus dorsi and the bottom portion of the serratus anterior.

Embryology

It’s unclear where the tissue that gives rise to the serratus anterior originated exactly. The serratus anterior starts to separate from the mesenchyme at the ventral ends of the lower cervical myotomes in the 9 mm embryo. The pre-muscle mass is now a continuous column that stretches over the ribs and vertebrae without any clearly defined attachments. The 11 mm embryo contains a well-defined muscular column extending from the cervical region to the thorax, which will develop into the serratus anterior.

The thoracic section gradually gets more slender in the caudal region and produces discrete digitations to the upper nine ribs. It eventually develops into the future serratus anterior muscle. While attachments to the cervical vertebrae have developed at this point, the serratus anterior has not yet fused to the scapula. When the serratus anterior differentiates into a broad, flat muscle that joins to the scapula, it starts to resemble the adult form in the 14 mm embryo.

Action

Scapular protraction, or moving the scapula anterolaterally around the thorax (toward the front of the body), is the main job of the serratus anterior muscle. Furthermore, the serratus anterior collaborates with the trapezius muscle to facilitate the upward rotation of the scapula. Because it tilts the glenoid cavity upward and preserves joint alignment, upward scapular rotation is essential for lifting the arms. The serratus anterior can assist in breathing when the shoulders are immobile by raising the ribcage.

The serratus anterior has three unique segments: the inferior segment helps with upward scapular rotation, the middle segment pulls the scapula forward, and the superior segment acts as the primary axis of rotation. The superior portion of the serratus anterior acts as the primary axis of rotation, while the intermediate segment pulls the scapula forward and the inferior section can rotate the scapula upward. The subscapularis bursa or supra serratus bursa divides the deep-lying serratus anterior muscle from the subscapularis. The serratus anterior is separated from the rib by the scapulothoracic bursa, also known as the infraspinatus bursa. Based on its locations of insertion and origin, the serratus anterior muscle is further split into three sections: the serratus anterior superior, serratus anterior intermediate, and serratus anterior inferior.

The first and second ribs are the source of the serratus anterior superior, the second and third ribs are the source of the serratus anterior intermediate, and the fourth and ninth ribs are the source of the serratus anterior inferior. The inferior segment rotates upward, the middle half pulls the scapula forward, and the superior segment acts as the primary axis of rotation.

Anatomical Variation

Each person may have a different serratus anterior origin and rib attachments. As an example, the serratus anterior may be linked to the tenth rib or it may not be attached to the first rib at all. Sometimes, the fibers of the levator scapulae, external intercostals, or external oblique muscles will unite with the serratus anterior fibers. Additionally, there have been documented variations in the vascular system, particularly in the blood flow to the serratus anterior myo-osseous flap. As a result, the lateral thoracic artery now serves as the primary source of blood for the lower muscle slips.

Furthermore, vascular linkages between the anteriorly located lateral thoracic pedicle and the periosteum of the ribs were identified from harvested sixth and seventh ribs. These connections differ from the more frequently reported connections of the branches from the thoracodorsal pedicle. Additionally, C4 or C5 may innervate the higher digitations of the serratus anterior separately, without the nerves merging to produce the long thoracic nerve’s main stem.

Surgical Considerations

When the long thoracic nerve or accessory nerves are damaged, the serratus anterior or trapezius muscles become paralyzed, resulting in a winged scapula. This condition manifests as a significant protrusion in the inferior angle of the scapula, accompanied by a restricted range of motion and strength in the shoulder. The long thoracic nerve is more exposed to injury after thoracic treatments such as radical mastectomy, transthoracic sympathectomy, misdirected intercostal drains, axillary lymph node dissections, and first rib excision.

Long thoracic nerve damage and winged scapula are risks associated with infants and children undergoing procedures that require separation of the latissimus dorsi and serratus anterior muscles, such as a posterolateral thoracotomy incision forclosed heart procedures. Because the roots of the long thoracic nerve can lie posteriorly, anteriorly, or pass through the middle scalene muscle, variations in the relationship between the long thoracic nerve and the muscle are also important to note because they may result in iatrogenic injury to the long thoracic nerve and consequent scapular winging.

While physical therapy is the primary treatment for winged scapula, surgical intervention using split pectoralis major transfer without fascial graft is an option for winged scapula related to serratus anterior palsy. This method involves moving the pectoralis major’s sternal head from the humeral insertion to the inferomedial region of the scapula. The use of nerve grafting and transfer has increased recently.

Clinical Significance

Myofascial pain syndrome may arise from repeated microtrauma to the serratus anterior muscle. Prolonged, forceful coughing, frequent overhead lifting of large objects, and long-distance running are some of the suggested processes. The condition known as serratus anterior myofascial pain syndrome may result from blunt trauma to the muscle. Individuals suffering from this illness report having main discomfort that is restricted to the fifth and seventh ribs in the midaxillary line. In addition, patients may have pain that is localized to the posterior chest wall and radiates to the palmar aspects of the fourth and fifth fingers on the ipsilateral upper extremity.

Anesthesia-induced nerve compression or Saturday night palsy—a radial neuropathy brought on by dozing off with one’s arm draped over a chair’s armrest—can cause long-term harm to the thoracic nerve. Excessive weight bearing can also trap the nerve, causing the serratus anterior to atrophy and the scapula to wing. Overuse and athletics can cause nerve traction. Additional causes of nerve injury include electric shock, severe trauma, exposure to cold temperatures, vaccinations, viral infections, and brachial neuritis.

Assessment Of Serratus Anterior Muscle

Palpation

The thin serratus anterior muscle covers the side of the ribcage.

The serratus anterior’s primary portion can be felt between the latissimus dorsi and pectoralis major muscles, deep to the scapula and pectoral muscles.

Muscle Test

The serratus anterior muscle weakening and scapula winging can be assessed using the three tests listed below.

The serratus anterior muscular weakness and scapula winging are assessed using the Serratus Anterior Strength Test or PushOut Test. Test of shoulder abduction. The therapist delivers a downward resisting force against the shoulder’s abduction at a range of 120 to 130 degrees, as well as an upward resisting force against the scapula’s rotation. A patient with weak serratus anterior would be unable to withstand the therapist’s force, which would cause the shoulder to break into adduction and limit the scapula’s ability to rotate upward.

The final test involves the patient sitting or lying down, with his elbow stretched to its maximum range and his arm flexed 90 to 100 degrees. The patient tries to push back as much as possible, but the therapist resists. When a patient has weakness in the serratus anterior muscles, their scapula is pushed back and internally rotated, which gives the appearance of winging on the scapula.

Exercises of Serratus Anterior Muscle

Serratus Anterior Muscle Of Stretching Exercise

Stretch In Side Lie

- Put yourself on your side.

- The side next to the floor should be the one being stretched

- Place your forearm on the ground and raise your torso.

- Throughout this stretch, make sure your upper arm remains perpendicular to the floor.

- Put all of your body weight into the shoulder.

- Maintain a completely relaxed shoulder.

- Lower your upper body to the floor.

- Breathe deeply and slowly into the side of your rib cage.

- Try to feel your side ribs getting stretched.

- For thirty seconds, maintain this posture.

Floor Stretch

- On your stomach, lie down.

- Put yourself in the bottom push-up position.

- Under the hand that is on the side, you want to stretch, place a block.

- Draw the shoulder blades back.

- Put your hand on a block and shift your weight to your shoulder.

- Shift your torso to the other side.

- For 30 seconds, hold.

Chair Stretch

- Take a seat in a chair.

- Put your hand on the edge of the chair backing by reaching behind you.

- Draw the blade of your shoulder back.

- Hold the hand firmly in the chair.

- Raise your elbow a little bit.

- Maintain a completely relaxed shoulder.

- Shift your body to the side.

- For 30 seconds, hold.

Wall Stretch

- Put your hand shoulder height against a wall.

- Take a lunge posture.

- Draw the blade of your shoulder back.

- Your body weight should be leaned into the wall-mounted arm.

- Shift your torso to the other side.

- For 30 seconds, hold.

Side Sitting Lean

- Lie on your side on the ground.

- Put your hand down on the ground to the side of your body.

- Throughout this stretch, maintain this arm’s perfect straight posture.

- Put all of your weight on this arm.

- Remember to maintain a completely relaxed shoulder.

- Bend your upper body to this side.

- As you shift more of your body weight onto the arm, lift your hips slightly off the ground.

- For 30 seconds, hold.

Hanging Stretch

- Put yourself on your side.

- The upper portion will be the focus.

- Retain the proper amount of weight.

- Set your arm straight so that it is parallel to the ground.

- Throughout this workout, maintain this arm’s straight posture.

- Stretch and raise your arm in the direction of the roof.

- As you gradually reduce the weight, pull your shoulder blade in the direction of your spine.

- The scapula should be sliding back onto the rib cage to move.

- Make twenty repetitions.

Arm Stretch

- Maintain an upright posture and erect back.

- With the left elbow slightly bent, place the left arm behind the back.

- With your right hand, reach behind your back and seize hold of your left wrist.

- Gently bring the left hand up to the right hip.

- Feel a deep stretch by lowering the right ear towards the right shoulder.

- Repeat on the right side after holding this stretch for ten to twenty seconds.

Doorway Stretch

- Position yourself in the doorway, standing. Stand erect and align your spine.

- Grasp the door frame with your left hand at shoulder height.

- Point the fingers in the direction of the roof.

- Pull the left scapula toward the spinal column.

- Once the left arm is behind you and the upper body is facing forward, keep the left palm firmly planted and turn the opposite side of the body toward the right.

- Repeat on the other side after holding the stretch for ten to twenty seconds.

- Stop the stretch immediately and speak with the physical therapist if the patient experiences any pain.

Crescent Side Bend

- Maintain a straight posture and back.

- Place your palms together and extend your arms toward the ceiling.

- Lower the shoulders away from the ears by sliding the scapulae down the back.

- Curl your upper body laterally to the left, while pressing your hips out to the right.

- Repeat on the left side after holding the stretch for ten to twenty seconds.

Bear hug

- Just above the level of your head, tie off the resistance band behind you.

- With your back to the resistance band, take a proud stance.

- Put the resistance band between your hands now.

- Return your arms to being in front of you. For 20 seconds, hold that motion to feel a stretch. Three to four times, repeat.

Serratus Anterior Muscle Of Strengthening Exercise

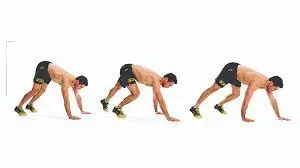

Bear Crawl

- This is a bodyweight mobility exercise that can strengthen your core muscles, raise your heart rate, and burn calories.

- Place your hands and feet shoulder-width apart on the ground and lie down to perform the bear crawl.

- Move your left leg as you move your right arm and your right leg as you move your left arm as you crawl forward in an alternating motion pattern.

- Bear crawls can strengthen our upper and lower limbs with good form and consistent exercise.

Scapular pull-up

- This exercise involves an upper-body workout that works the shoulder and back muscles by using a smaller range of motion than a standard pull-up.

- Increased upper-limb strength results from scapular pull-ups performed correctly by the patient.

- Scapular pull-ups primarily target the lattisimus dorsi, trapezius, rhomboids, and serratus anterior muscles.

- Start the scapular pull-up with your elbows slightly bent in the dead hang position.

- To tighten the shoulder blades together and raise your torso a little bit, perform a reverse shrug.

- Before lowering yourself back to the beginning position, hold at the highest position.

- Perform ten repetitions in a row.

- Work out three times a day.

Dumbbell Pullover

- It’s a weightlifting exercise that works the lattisimus and pectoralis muscles.

- To perform this exercise, lie back on the flat bench with a single dumbbell in your hands. Engage the core and keep the lower back in contact with the bench.

- Lift the dumbbell above the chest to lengthen the arms.

- Return to the starting posture above yourself after lowering the dumbbell with caution behind your head.

- In one session, perform two to three sets of ten to fifteen repetitions of this.

- Work out twice a day.

Wall slides

- A patient must stand straight, place their feet shoulder-width apart, and press their back flat against the wall to perform wall slides. Flex the elbows at a ninety-degree angle and elevate the arms against a wall.

- The elbow and the underarm should be parallel to the floor. The backs of the hands ought to be in contact with a wall. Bend your knees gradually while keeping your body in contact with a wall, until your knees are at a 45-degree angle.

- Straighten the arms above the head until they are perfectly straight while flexing the knees.

- At the bottom of the motion, hold for five seconds.

- After the required number of repetitions per session, return to the embark position and repeat.

- Work out twice a day.

Rhomboid Pull

- The best exercises for strengthening the serratus anterior are as follows.

- Start by placing your feet shoulder-width apart. Raise your arms so they are parallel to the floor and shoulder height.

- Next, bring your elbows back, flex your elbows, and contract your shoulder blades.

- Go back and do it again. When you pull back, exhale, and when you come back, inhale. Verify that the arms are in line with the floor.

- Maintain a contracted triceps.

- In a single session, complete three sets of 15–20 repetitions.

- Work out three times a day.

Wall Push-up

- To do this exercise, the patient must stand about two feet away from the wall, place their hands on the wall, and raise their fingers to eye level.

- Lean forward from the trunk and flex the elbows until the patient gets a nice stretch in the shoulders and chest—not too much that it hurts.

- At this point, push yourself away from the wall to do the exercise one more time.

- This exercise is identical to normal pushups except that the hands are put on top of the wall or other elevated surfaces.

- With this additional leverage, the serratus anterior muscles—which are located directly beneath the pectorals—will be given greater attention.

Serratus Punch

- By strengthening the serratus anterior, or chest wall muscle, this exercise serves to form the pectoral muscles in a way that can enhance the strength of the upper limb muscles.

- The patient must stand in a split stance with their feet apart, knees slightly bent, and their back to the pulley or even elastic band device.

- Next, with the scapula in the retracted position, the humerus internally rotated 45 degrees, and the elbow fully extended, the handle of the pulley or even resistance band is held at shoulder height.

- Then, as the arm is raised, there is a prolonged and retracted scapula motion in the direction of 120 degrees because the activity of the serratus anterior tends to grow slightly linearly. Finally, please do it again with the opposite hand.

Side Plank

- This exercise will assist in strengthening the serratus anterior and enhancing the patient’s core endurance.

- The patient must lie on their left side for this exercise, keeping their elbow slightly bent on the floor and their palms resting on top of one another. As the patient is stacked towards one shoulder, make sure both of their toes are looking downward.

- Elevate your hips off the ground and maintain a straight body for a duration of 30 to 40 seconds.

- Perform this exercise in two sets of ten to fifteen repetitions every session. Perform this workout twice a day.

Eccentric Strengthening Exercise

- Put yourself on your side.

- The upper portion will be the focus.

- Retain the proper amount of weight.

- Set your arm straight so that it is parallel to the ground.

- Throughout this workout, maintain this arm’s straight posture.

- Stretch and raise your arm in the direction of the roof.

- As you gradually reduce the weight, pull your shoulder blade in the direction of your spine.

- The scapula should be sliding back onto the rib cage to move.

- Make twenty repetitions.

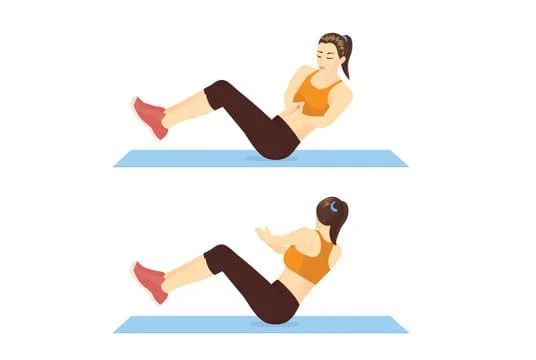

Long Arm Crunches

- The serratus anterior, which lifts the shoulders, and the abdominal muscles will both be toned with this exercise.

- The patient must lie on their back with their feet flat on the ground to perform this exercise.

- Next, extend your arms above your head. Place one hand over the other.

- Raise shoulders off the floor and lower softly back down. Make use of your abdominal muscles. Breathe in when he lowers them and out when you raise the shoulder.

- Spend 30 to 40 seconds doing this.

- This can also be done by the patient on the exercise ball.

Russian Twist

- It is an excellent serratus anterior muscle exercise.

- The patient must sit with their feet slightly elevated and their back tipped backward for this exercise.

- presently, Twist from side to side while holding your hands together. Exhale when the twist happens. When turning, keep your legs motionless.

- The neck ought to be in a neutral position. Pull in your abdominals. this is for forty seconds. Verify that the patient’s legs are not moving.

- Use exercise balls to support his legs if he is unable to hold them still.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the serratus anterior muscle stands as a pivotal component of the upper body musculature, contributing significantly to shoulder stability, mobility, and overall functional movement. Its role in protraction, upward rotation, and stabilization of the scapula is crucial for various daily activities and sports performance.

Maintaining the strength and integrity of the serratus anterior muscle is essential for optimal shoulder function and injury prevention. Understanding its anatomy and function empowers individuals to incorporate targeted exercises and rehabilitation strategies to address weaknesses or imbalances, ultimately enhancing overall upper body strength, posture, and movement efficiency.

As a key player in both athletic performance and everyday tasks, the serratus anterior muscle deserves recognition for its indispensable role in supporting a healthy and functional upper body.

FAQ

What is the functional anatomy of the serratus anterior muscle?

It inserts throughout the whole length of the anterior face of the medial border of the scapula, starting at the side of the chest from the upper 8 or 9 ribs. The brachial plexus provides the long thoracic nerve that innervates it. The serratus anterior pulls the scapula forward around the thorax.

What are the benefits of the serratus anterior?

The serratus anterior is a muscle in the chest that is deeper than some others, yet it is still important to work out. Maintaining the strength of this muscle will help you prevent pain in your neck, shoulders, and back, as well as help with posture and breathing. It will also enable you to lift and move your arms fully.

How do I strengthen my serratus anterior?

Scapular Push-up.

Push-up.

Push-up Plus.

Unilateral Banded Chest Press.

Wall Slides.

Dumbbell Pullover.

Ab Rollout.

Dumbbell Rotational Punch.

Which muscle is called Boxer’s muscle?

All three components of the serratus anterior muscle cooperate to raise the ribs and aid in breathing when the shoulder girdle is stabilized. The protraction of the scapula, which happens when delivering a punch, is mostly caused by the serratus anterior, popularly referred to as the “boxer’s muscle.”

Can weak serratus anterior cause neck pain?

Recuperation appears to be worse after surgery and more likely and quicker following infection. People who are paralyzed or have serratus anterior weakness usually complain of pain in the shoulder, around the shoulder blade, and up into the neck.

What does serratus anterior pain feel like?

Pain over the fifth to seventh ribs along the midaxillary line is a common symptom of serratus anterior myofascial pain syndrome. Pain can radiate to the anterior chest wall, the medial aspect of the arm, the medial border of the scapula, and occasionally toward the fourth and fifth digits, simulating radiculopathy.

What happens when serratus anterior is tight?

Because of the attachments of the serratus anterior muscles, our body will attempt to use a “alternative muscle” to complete the movement if the muscle is tight or weak. Typically, this means using the upper trapezius or levator scapulae muscles.

What is the nerve to serratus anterior’s root value?

The serratus anterior muscle, which attaches the scapula to the chest wall, is innervated by the long thoracic nerve, which arises from the C5–C7 roots and descends in the axilla, posterior to the brachial plexus. Winging of the scapula is caused by injuries to the long thoracic nerve, particularly while the arm is in anterior abduction.

Is the serratus anterior attractive?

Maybe the sexiest muscle on a man’s body is the serratus anterior. When fully developed and shredded, this muscle group on the side of your rib cage resembles shark gills.

What nerve is serratus anterior?

Shoulder protraction is mainly caused by the serratus anterior muscle, which is innervated only by the long thoracic nerves. Additionally, it cooperates with the trapezius to provide the scapula with the continuous upward rotation required for overhead lifting

Reference

- Serratus Anterior. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Serratus_Anterior

- Lung, K., St Lucia, K., & Lui, F. (2024, February 1). Anatomy, Thorax, Serratus Anterior Muscles. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK531457/

- Serratus anterior muscle. (2024, May 2). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serratus_anterior_muscle

2 Comments