Knee injuries are a common, frequently painful medical condition that can impact people of all ages and activity levels. The knee joint is a complex structure comprised of bones, ligaments, tendons, and cartilage, all of which cooperate to support and facilitate a range of movements.

However, the knee may suffer injuries from a variety of sources, including overuse, degenerative diseases, and traumatic events.

Due to their pain and limited movement, these injuries can significantly affect a person’s day-to-day functioning. Due to the repeated strain of sports activities on the knee, athletes are especially at risk for knee injuries. In addition, the aging process and other medical problems might eventually cause the knee to weaken.

Many types of moderate knee pain are effectively treated with self-care strategies. Orthopedic braces and physical therapy are other choices for pain management. However, there are situations where knee surgery is necessary.

Introduction:

Damage to one or more of the tissues that make up the knee joint, such as the muscles, tendons, cartilage, bones, and ligaments, causes injuries to the joint. These injuries may result from high impact from an automobile crash, falling, quickly twisting the knee, or other traumas. Sprains, dislocations, and fractures are common knee injuries.

The knees stabilize the body and allow the legs to bend and straighten. Since the knee is the body’s largest joint, injuries frequently arise. The four main tissue types that make up the knee are ligaments, cartilage, tendons, and bone. Damage to any of these important tissue types can result from an injury.

Two common sports-related knee injuries are meniscus tears and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears. High-impact trauma can result in patella (kneecap) fractures, though they are less common in sports. Most knee injuries require immediate medical attention; some may even require surgery.

The knee can lead to a broad variety of injuries because of its complex structure and variety of parts. Among the most common injuries to the knee are sprains, tears in the ligaments, fractures, and dislocations.

Many knee problems can be easily treated with straightforward measures like bracing and rehabilitation exercises. Other injuries can require surgery to be repaired.

Knees give the body stable support while allowing the legs to bend and straighten.

Since the knee is the body’s largest joint, injuries frequently happen. In the knee, cartilage, tendons, ligaments, and bones are the four main tissue types. Any of these basic tissue types can be harmed.

Typical knee injuries include:

- A sprain is an excessive tearing of the ligaments in the knee.

- Pain in the kneecap region.

- Excessive stretching of the muscles and tendons or strains.

- Meniscus tear (the shinbone and thighbone are separated by cartilage).

- Ligament rupture, such as the anterior cruciate ligament or posterior cruciate ligament.

- Injury to the knee’s protective cartilage.

Less frequent knee injuries include:

- Fractures (usually caused by landing on the knee, twisting, or being hit directly).

- Dislocations of the kneecap.

- Since they require a lot of force, dislocations of the knee are rare.

Anatomy:

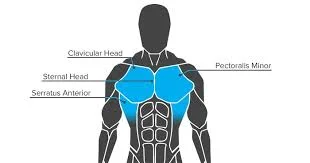

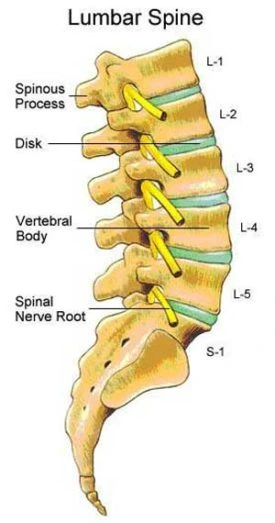

The knee is the largest and most commonly damaged joint in the body. Its four primary structural elements are cartilage, tendons, ligaments, and bones.

Bones

- The femur (thighbone), tibia (shinbone), and patella (kneecap) combine to form your knee joint.

- The patella lies in front of the joint to provide a little protection.

Articular cartilage

- This tissue lines the back of the patella, the femur, and the tibia. Your knee bones can move more smoothly as you stretch or compress your leg due to the smooth surface mentioned earlier.

- The meniscus between your femur and tibia are two wedge-shaped sections of meniscal cartilage that act as shock absorbers.

- Compared to articular cartilage, the meniscus, which helps in stabilizing and supporting the joint, is stronger.

- When someone refers to a torn meniscus, they typically mean a torn fragment of knee cartilage.

Ligaments

- A bone is joined to another bone by ligaments.

- The four main ligaments in your knee function as strong ropes to keep the bones of your knee together and your knee solid.

Tendons

- Tendons help with joining muscles and bones.

- The quadriceps tendon serves as a connection between the patella and the front leg muscles.

- In contrast, the patella and tibia are joined by the patellar tendon.

Collateral ligaments

- Both of these sides of your knee have them.

- The medial collateral ligament is found inside your knee, whereas the lateral collateral ligament is found outside.

- They control how your knee moves from side to side.

Cruciate ligaments

- These are found inside the knee joint.

- The anterior cruciate ligament and posterior cruciate ligament cross each other to form an X with the anterior in front and the posterior in back.

- The cruciate ligaments control the front and posterior motions of your knee.

The mechanism of injury:

Given the potential seriousness of both acute and chronic knee injuries, many investigations have attempted to explain the extrinsic and intrinsic components that contribute to these injuries.

Extrinsic effects include shoe wear, training surface conditions, and training program; intrinsic factors include ligamentous laxity, reduced muscular flexibility, muscle weakness, and foot shape.

Studies on acute knee injuries have mostly focused on American football and soccer players. One extrinsic aspect studied in American football players is shoe type. In the 1970s, high school football players reported fewer knee and ankle problems when they wore “soccer-style” shoes.

Compared to conventional footwear, these athletes’ shoes featured more cleats, which were larger and shorter. Following the establishment of cleat size and length standards by the National Collegiate Athletic Association and the National High School Athletic Union, these results led to the measurement of torque forces.

Overuse injuries can result from using running shoes that are too small or large for the runner’s foot type or from failing to replace the midsole of an old shoe when it begins to lose its ability to absorb pressure. Chronic injuries can result from running on the same banked edge of a road or track, training on hard surfaces, or running on difficult surfaces like sand or hills.

Overuse injuries usually appear in the first few weeks after starting a new training program or significantly increasing its intensity. Injuries can also occur to athletes who move from high school to university competition and whose training becomes more intense. It’s important to counsel athletes to progressively improve the volume and intensity of their workouts.

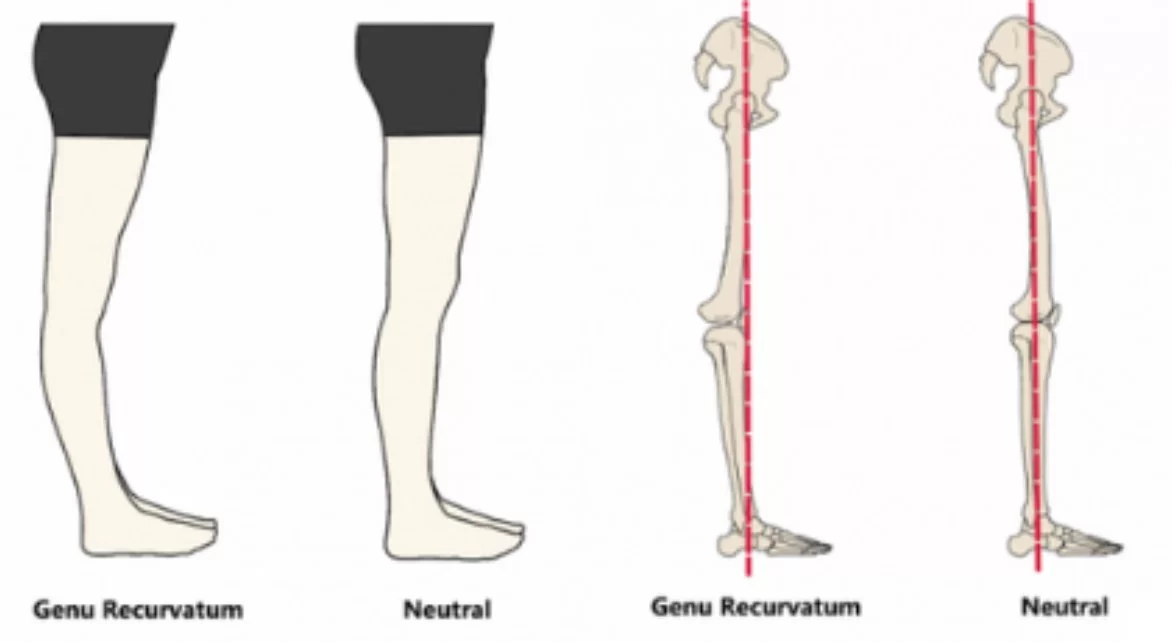

Benign hypermobility syndrome and consequently common ligamentous laxity have been connected to several overuse injuries, including patellofemoral pain syndrome. However as multiple studies have shown, there is no link between benign hypermobility syndrome and the prevalence of ligamentous laxity in football players or injuries to the knee.

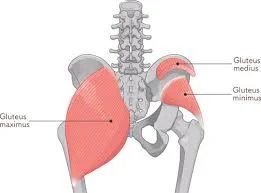

Weakness of the core (abdominal, paraspinal, and buttock muscles) may result in instability that may need increased knee activation and loading. Quadriceps weakness is another complication of acute knee effusions and is frequently associated with overuse injuries to the knee.

Weaker calf muscles, hip flexors, iliotibial band syndrome, and hamstrings might lead to decreased knee stress and the risk of overuse injury. Knee injuries may be more common in athletes with pes planus, pes cavus, or unusual foot shapes.

Common Injuries to the Knee:

The most common injuries to the knee include sprains and tears of soft tissues (such as ligaments and meniscus), fractures, and dislocations. Injuries frequently involve more than one knee structure.

When a knee injury happens, pain and swelling are the most typical symptoms. Moreover, the knee may lock or catch. Some types of knee injuries, such as anterior cruciate ligament tears, can cause instability, or the feeling that your knee is giving way.

Many moving elements make up the knee joint. People can sit, squat, jump, and run using it since it functions similarly to a door hinge and allows users to bend and straighten their legs.

The knee consists of four parts;

- Ligaments

- Bones

- Tendons

- Cartilage

The femur, often known as the thighbone, is located at the apex of the knee joint. The tibia or shinbone makes up the basis of the knee joint. The femur and tibia joint is covered by the patella, commonly known as the kneecap.

The substance that protects the knee joint’s bones is called cartilage. It also protects the bones from impact and supports the movement of ligaments over them.

The four ligaments of the knee work like ropes to provide stability and hold the bones together. The muscles that support the knee joint are attached by tendons to the lower and upper leg bones.

Here is a list of the most typical knee injuries,

Injury to the Knee Ligament

A joint is surrounded by strong bands of connective tissue called ligaments that support and control mobility. Ligament injuries, often known as knee sprains, can result from sports injuries that create instability in the knee joint. They also make it difficult for you to move your knee as much.

The knee is stabilized by four primary ligaments that connect the thigh and shin bones;

An anterior cruciate ligament (ACL): The middle knee ligament, known as the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), controls how the shin bone rotates and moves forward. Tears or sprains of the anterior cruciate ligament caused by sudden pauses, changes in direction, jumping, and landings are known as anterior cruciate ligament injuries. It’s common in sports like basketball, football, and downhill skiing.

A posterior cruciate ligament (PCL): The ligament in the middle of the knee that controls the shin bone’s rearward mobility is called the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). A strong, sharp impact, usually from a football hit or other comparable activity, can strain or tear your knee’s strongest ligament, the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) causing injury.

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL): The ligament responsible for supporting the inside knee is called the lateral collateral ligament (LCL). The lateral collateral ligament can become injured during activities that require twisting, bending, or sudden changes in direction. A football player getting hit on the inside of the knee is one example.

Medial collateral ligament (MCL): The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is an outside knee ligament that promotes stability. An injury known as a medial collateral ligament sprain can happen to someone who gets hit on the outside of the knee, like in a football or hockey match.

In the direction that the wounded ligament stabilizes, the knee becomes unstable when any one of these four is damaged. The four particular tests used to evaluate injuries are the Varus Stress Test ( lateral collateral ligament ), the Valgus Stress Test for (medial collateral ligament ), the Anterior Dawer Test for (anterior cruciate ligament), and the Posterior Dawer Test for (posterior cruciate ligament).

Signs and symptoms of an injury to the knee ligament:

- There was a loud pop, or snap, at the scene.

- Sudden, unbearable pain that sometimes prevents you from practicing your sport.

- Black and blue discoloration surrounding the knee.

- Instability of the knee.

- Swelling that appears within the first twenty-four hours after an injury.

- Pain restricting the damaged joint from supporting weight.

- Bending the knee with the outside inward.

To identify ligament damage, a doctor first performs a physical examination. They will examine the knee to look for swelling and pain. The technique may cause pain because of the many knee movements that are utilized to evaluate your range of motion and the external pressure that is given to your knees.

Although ligament injuries happen often, there is variation in the degree of the injury;

Grade I:

- A Grade I injury results in a little overworked fiber, which causes ligament spraining.

- There won’t be many bruises or any swelling at all.

- A prime example of this type of injury is a medial collateral ligament sprain.

Grade II:

- This is the result of partial, but incomplete, rupture of the ligament fibers.

- Compared to Grade I, there will be more pain, joint limitation, bruising, and swelling.

Grade III:

- A whole tear in the ligament generates a Grade III injury, which is usually quite painful.

- The area around the knee will be severely swollen and bruised.

- An example of this type of damage is a lateral collateral ligament tear.

The degree of damage is divided into three categories using a grading system: Grade I (mild), Grade II (moderate), and Grade III (severe). The type of sprain, the severity of the injury, your recovery strategy, and the type of sport you play all affect how long a knee sprain lasts.

Many times, minor to moderate wounds heal on their own. For most collateral ligament tears, surgery is usually not required (medial collateral ligament and lateral collateral ligament). However, in situations where the cruciate ligaments (anterior cruciate ligament or posterior cruciate ligament) have been severely ripped and strained, reconstructive injury will be the only option. Should you obtain proper medical attention and engage in a high-quality physical therapy treatment, a full recovery should to be achievable.

Injury to the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL):

Sports participation frequently results in anterior cruciate ligament injury. Sports involving eliminating and turning, such as soccer, football, and basketball, are more likely to cause anterior cruciate ligament injuries in athletes.

An anterior cruciate ligament tear can be caused by sudden changes in directions or by landing from a jump incorrectly. About 50% of anterior cruciate ligament injuries also involve damage to other knee components, such as articular cartilage, the meniscus, or other ligaments.

The stability of the joint depends on the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), which runs diagonally down the front of the knee. Surgery may be required for anterior cruciate ligament injuries, which can be rather dangerous.

Anterior cruciate ligament injuries have a numerical value that goes from one to three. A grade 3 sprain is an anterior cruciate ligament tear, while a grade 1 sprain is regarded as a moderate injury.

Anterior cruciate ligament injuries are common among athletes who play contact sports like football or soccer. However, contact sports are not the primary cause of this illness.

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL):

The posterior cruciate ligament is commonly injured when the knee is bent and pushed in the front. This usually happens in crashes between sports vehicles and automobiles. The majority of tears in the posterior cruciate ligament are partial tears that could heal on their own.

The posterior cruciate ligament is situated behind the knee. This ligament is one of several that connects the thighbone to the shinbone. This ligament restricts the amount of backward movement of the shinbone.

A posterior cruciate injury requires force when the knee is bent. This kind of stress is typically experienced after serious falls onto a bent knee or after being injured in an incident that results in a bent knee.

Injury to the Collateral Ligaments:

In most cases, collateral ligament injuries are caused by an external force that forces the knee sideways. These are often contact-related injuries.

Sports-related trauma is a common cause of medial collateral ligament injuries, which are primarily caused by direct impacts to the outside of the knee.

An injury to the inside of the knee that results in the knee bending outward can harm the lateral collateral ligament (LCL). Compared to other kinds of knee injuries, lateral collateral ligament tears happen less commonly.

The shin and thighbone are joined by collateral ligaments. Athletes frequently suffer these injuries, especially those who participate in contact sports.

Direct hits or accidents with other persons or objects frequently result in tears to the collateral ligaments.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome:

Pain near the patella, or kneecap, is the feature of patellofemoral pain syndrome, also referred to as “runner’s knee.” This illness is caused by imbalances and abnormalities in the surrounding muscles and tissues. It is common among athletes who perform knee flexion exercises repeatedly, such as running, leaping, and cycling.

Signs and Symptoms of Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome:

- A dull, sharp pain in the front of the knee.

- Pain that worsens with prolonged sitting, squatting, and climbing stairs.

- Buckling or bending to the knee irregularly.

Physical therapy can be used to strengthen the muscles surrounding the knee, increase flexibility, and deal with imbalances. Orthotics or shoe inserts can also be used to support the feet and reduce stress on the knee joint.

Meniscal Tears:

Meniscal tears resulting from sports are prevalent. Meniscus tears are possible when a person is tacking, twists, cuts, or pivots for movement. Arthritis and age can also cause meniscal tears. A simple awkward twist when getting out of a chair could cause an injury if your meniscus becomes weaker with age.

When someone refers to torn knee cartilage, they most likely point to a meniscal tear.

Menisci are the two flexible cartilage wedges that rest between the shin and thighbones. These cartilage parts may suddenly burst during sports. They may also tear more slowly as they get older.

Natural aging-related meniscus tears are referred to as “degenerative meniscus tears.”

A meniscus tear that happens suddenly can cause a pop in the knee. The pain, swelling, and tightness may worsen in the days that follow the initial injury.

An elastic cartilage that supports the knee with a crescent-like shape is called the meniscus. Often suffered in sporting locations meniscal tears are a common kind of knee injury that can result from severe trauma or abrupt twists.

The injury and ligament damage can happen at the same time. The degree of the injury might also vary, ranging from mild to severe, depending on how far it goes.

Signs and Symptoms of A Meniscal Injury;

- Localized pain on the medial or lateral surfaces of the knee.

- Locking and clicking noises.

- A delayed onset of intermittent swelling.

Diagnosing a torn meniscus begins with a thorough history and physical examination. To confirm a diagnosis, imaging tests such as an MRI, X-ray, or arthroscopy could also be required.

It is recommended that meniscal injuries be treated early with the RICER approach, which stands for rest, ice, compression, elevation, and reference. This strategy needs to be followed within 48–72 hours to receive quick medical attention and pain relief. In addition, you must follow the No HARM plan, which restricts the use of heat, alcohol, running, and massage. It reduces the bleeding and edema in the wounded knee.

Physical therapy can help you strengthen the muscles in your legs and around your knees, which can provide stability and support for your knee joints. The patient may need to wear a knee brace designed specifically for helping a meniscus tear. If, however, your knee locks up and the pain doesn’t go away after treatment, the doctor might recommend surgery.

A good prognosis can be obtained after a meniscal tear. To achieve this, patients might either have surgery or get conservative therapy. Athletes can compete in their original sports. It’s also true that once damage happens, cartilage cannot be repaired to its original state. To avoid a torn meniscus, everyone needs to check out preventative measures (such as strengthening the surrounding muscles, keeping a healthy weight, or employing proper body mechanics).

Bursitis:

Little sacs filled with fluid called bursae protect the knee joints and make it easier for tendons and ligaments to pass over them.

These sacs have the potential to expand and become inflamed when they are overused or frequently compressed while kneeling. This is referred to as bursitis.

For the most part, bursitis is not serious and can be treated with self-care. However, aspiration a procedure using a needle to remove excess fluid as well as antibiotics can be required in specific situations.

The knee bursae are little sacs that are filled with fluid and are situated near the knee joint. When they are in good working order, they help guide joints smoothly and keep tendons, ligaments, and muscles from rubbing against the bones.

Knee bursitis arises from injury, inflammation, or irritation of one or more bursae. Bursitis can be caused by grating friction created by repeated activity such as jogging, strong blows, and chronic pressure. This worsens if the joint is immobilized for an extended amount of time.

Signs and Symptoms of Knee Bursitis:

- A sharp or stabbing sensation followed by a slow, aching pain.

- Swelling and redness in the anterior part of the knee.

- Warmth in the area surrounding the joint.

- Pain when bending over.

- Greater pain after a prolonged period of joint immobility.

Sometimes bursitis is mistaken for other illnesses, such as tendinitis, arthritis, and stress fractures. To correctly identify the problem, the orthopedic doctor or physical therapist will do a thorough examination and prescribe specialist testing such as an MRI, ultrasound, or X-ray.

Knee bursitis typically resolves on its own with little to no help from a doctor. The goal of an intervention is to reduce symptoms, however, in some cases, medical care can be required. This includes over-the-counter drugs, home remedies, and basic therapy including lifestyle modifications. Injections of corticosteroids, aspiration, and surgery are other possibilities for chronic problems.

Tendonitis:

Knee tendinitis or inflammation is known as patellar tendinitis. The tendon that connects the shinbone and kneecap gets damaged in this way. The patellar tendon works in conjunction with the front of the thigh to extend the knee, allowing for running, jumping, and other athletic activities.

A common ailment among athletes who jump frequently is tendinitis, commonly referred to as “jumper’s knee.” All those who are physically active, however, are at risk for tendinitis.

Patellar tendinitis, sometimes referred to as “jumper’s knee” or patellar tendinopathy, is characterized by overstressed knees. Athletes commonly get this form of injury in sports like the long jump, basketball, and volleyball where they frequently jump or fall hard. It also occurs when you increase your exercise routine unexpectedly or train on hard surfaces like concrete. The increased strain on the tendon results in tiny tears, which inflame the muscle.

Pain from patellar tendinitis typically goes away gradually. Athletes with mild to severe symptoms could potentially train and compete. When originally damaged, the wound often healed quickly and without any problems. However, if it happens frequently, the tears may start to form before the body heals. More damage will eventually take place, resulting in pain and malfunction.

Signs and Symptoms of Patellar tendinitis:

- Pain and soreness below the kneecap.

- Pain gets worse as you run, leap, jump land, and rest for extended periods.

- The knee is weak.

To diagnose the issue, your doctor will feel and inspect various portions of your knee to find painful regions. If you have patellar tendinitis, this will be located at the front of your knee, just behind the kneecap.

Doctors will often use imaging tests like MRIs, ultrasounds, and X-rays to get a more definitive diagnosis.

Additional medical procedures for this injury include physical therapy and maybe longer recovery. With the proper treatment and rehabilitation for your injuries, you may go back on the field, court, or track as soon as possible.

Tendon Tears:

The quadriceps and patellar tendons can be torn and stretched. Middle-aged adults who participate in sports involving running or jumping are more likely to experience tears, while injuries to these tendons may happen to anybody. Following jumping, an awkward landing, falls, and crashes direct force applied to the front of the knee are all frequent causes of injuries to the knee tendon.

The tendons, which are soft structures, are what attach the muscles to the bones. Knee injuries involving the patellar tendon are common. A middle-aged or athletic person who exercises regularly and often tears or overstretches their tendons. Additionally, a fall or attack that affects the tendon may cause it to rip, for example.

Iliotibial band syndrome:

It is common for long-distance runners to experience iliotibial band syndrome. It comes on by the iliotibial band, which is located outside the knee, sliding on the outside of the knee joint.

Pain is almost always the result of a minor issue. It may eventually get so severe that a runner has to stop running just to give their iliotibial band a chance to recover.

The iliotibial band (ITB) or iliotibial tract is the thick band of fascia that extends from the top of your shin to the length of your thigh. This structure is made up of dense fibrous connective tissue that inserts at the knee and begins at the iliac crest. The lateral rotation, abduction, and extension of the hip are controlled by the iliotibial band (ITB) and the muscles it engages.

Iliotibial band syndrome is thought to be caused by non-traumatic overuse injuries that result from underlying weakness in the hip abductor muscles. Running and cycling are the most common sports where people have outside-of-the-knee pain, This develops as a result of excessive knee flexion and extension. Sports like basketball, swimming, hockey, cycling, and hiking are also associated with it.

Iliotibial Band Syndrome Symptoms:

- Felt soreness or tightness on the outside of the knee.

- Pain that persists after exercising.

- A clicking sound.

- Warm, red skin surrounds the knee.

A diagnosis can be made with the help of your medical history, which details the symptoms and issues you are now experiencing. This will also include a physical examination and a thorough assessment of your knees’ strength and range of motion. Using certain tests, your doctor can rule out iliotibial band syndrome, meniscal tears, osteoarthritis, and other potential reasons for your knee pain. An X-ray or MRI would be required to reach an exact diagnosis.

Most people respond well to stretching, strengthening, applying cold compresses, and taking anti-inflammatory medications. It is also important to temporarily limit one’s activities to reduce pain, prevent further injury, and allow the knee to heal fully. It is occasionally advised to use ultrasound and electrotherapy to relieve stress. In the interim, some may even require surgery to treat the injury.

Most individuals with iliotibial band syndrome recover, however it usually takes them several weeks or months to return to their regular activities without pain.

Fractures:

Patellar fracture

The bone that breaks closest to the knee most often is the patella. The point where the tibia and femur unite to form the knee joint is also at risk of fracturing. The majority of fractures around the knee are caused by high-energy trauma, which includes car crashes and falls from significant heights.

Any of the bones in or around the knee could fracture. High-impact trauma, including falls or car accidents, is the main cause of knee fractures. For someone with underlying osteoporosis, even a minor mistake or fall might cause a knee fracture.

Patellar fractures are serious injuries to the knee that can seriously impede function. This may result from a direct landing on your kneecap, from overusing your knee, or from a direct hit or trauma. A fracture could occur if the tension builds up beyond what the bone can support. The site, degree, and kind of these injuries are subject to variation.

Signs and symptoms of patellar fracture;

- Suddenly, there is painful, stabbing pain at the front of the knee.

- An obvious problem in the knee.

- Inability to raise the foot.

- Visible abnormality (in extreme situations)

A physical examination, radiological results, and an analysis of the injury’s route of origin are used to make the diagnosis. Treatment may include repositioning, surgery, or the use of functional and protective devices (e.g., crutches, plaster casts, or knee braces). Gradual patellar conditioning is a safe and effective way to help athletes recover.

Patients with patellar fractures usually heal well if they receive the proper care. They can resume sports in a matter of weeks or months under the close supervision of their physical therapist or another specialist. If the rehabilitation following this type of fracture is not sufficient, conditions such as osteomalacia, patellofemoral pain syndrome, and post-traumatic arthritis may develop.

Osgood-Schlatter Disease:

This common overuse injury results in pain and inflammation in the growth plate located in the tibial tuberosity. It is particularly common in teenagers who play sports where they must sprint, jump, or change direction quickly, and it usually affects them at times of rapid development.

Signs and symptoms of Osgood-Schlatter Disease:

- Tibial tuberosity and swelling of the patellar tendon.

- The bony protrusion below the kneecap, known as the tibial tuberosity, is the source of the soreness, swelling, and stiffness.

- Pain that gets worse when you run, jump, or squat.

- Temporary relief from pain during bed rest.

Treatment usually includes rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE) together with anti-inflammatory medications and physical therapy to strengthen the surrounding muscles. Usually, the issue is resolved by the growth plate closing on its own.

Dislocation:

A dislocation happens if there is a partial or complete displacement of the knee’s bones. For instance, there could be a cause for the patella to shift or the tibia and femur to misalign.

Dislocations could be the result of a structural abnormality in the knee. When it comes to those with normal knee structure, high-energy trauma such as automobile crashes, sports injuries, and falls is the most common cause of dislocations.

Knee dislocation can occur when the knee’s bones are misplaced or out of alignment. A dislocated knee may result in one or more bones being displaced. Trauma or structural issues, such as those suffered in falls, car crashes, or contact sports, can cause a dislocated knee.

Knee dislocations can be classified as either high-velocity or low-velocity. High-velocity knee dislocations are most frequently caused by a violent force, such as a car accident. Conversely, low-velocity dislocations of the knee are common in displaying situations.

An athlete stands the danger of dislocating their knee when they quickly change direction after planting their foot on the ground. A twisting motion is present. In sports like gymnastics, long jumping, cycling, soccer, and skiing, this is typical.

Signs and symptoms of Dislocated Knee:

- Sudden and severe edema.

- Extreme stiffness and pain.

- Hypermobile patella, or “sloppy” kneecap.

- A noticeable abnormality of the knee.

- Below the knee, weakness or absence of pulse.

The doctor will initially check distal pulses, particularly on the foot, to rule out injury because vascular damage is frequently linked with knee dislocation. They may also recommend an X-ray to figure out the extent of bone injury. An arteriogram, or X-ray of the artery, may be given to patients to check for arterial damage, while an ultrasound may be used in certain cases to evaluate arterial blood flow.

Treatment consists of immobilization, surgery (which includes knee reconstruction and vascular repair to protect blood flow), and relocation (placing the lower leg back into position through a process called reduction).

One considers a dislocation to be a significant injury. The wounded knee usually loses its ability to endure stress, however recovery is possible. Bracing wraps or additional supports are often recommended by doctors to protect the knee and prevent it from being overused.

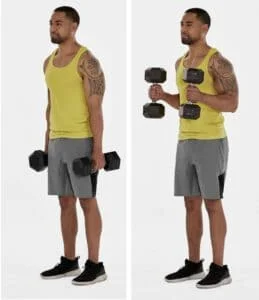

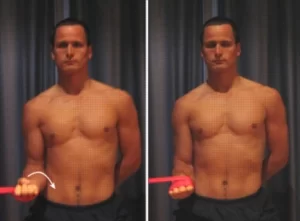

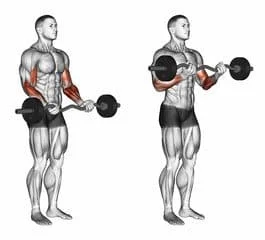

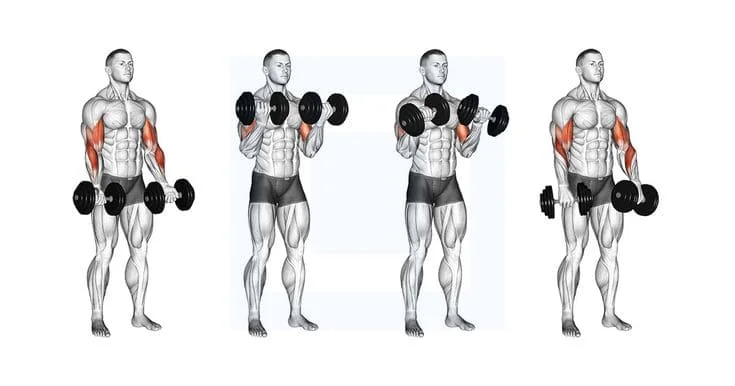

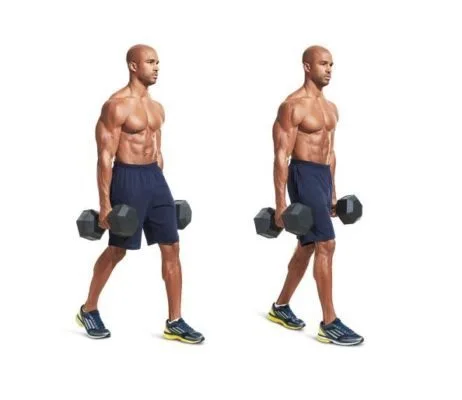

Hamstring & Quadriceps Strains:

Your thigh is made up of two primary muscle groups: the hamstrings and the quadriceps. The three muscles that form the hamstring are the biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus. From your thigh to your knee, they go along the back of your leg.

When these muscles work together, knee flexion and hip extension are possible. The quadriceps muscles are located in the area between your hip and knee on the anterior part of your thigh. They are joined to your pelvis, femur (thigh bones), patella (kneecaps), and hip bones through the related tendons.

Strains in the hamstrings and quadriceps are common ailments that arise from overstretching the tearing muscle fibers. These injuries are common in sports where players must sprint, jump, or change direction quickly.

Signs and symptoms of Hamstring And Quadriceps Strains:

- Acute, sharp pain that affects the thigh’s quadriceps or hamstrings.

- Both bruising and swelling.

- It is challenging to walk or bear weight on the injured limb.

Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation (RICE) is the standard therapy for these injuries to minimize pain and swelling. Physical treatment could also be necessary to help the affected muscles regain their strength and flexibility.

Which types of knee injuries following a fall are most common?

The most common knee injuries that can occur following a fall are these, which range in severity from mild to serious.

Contusion

- A bruise or contusion to the knee is a typical injury suffered from falling onto a hard surface.

- The impact may cause blood to leak into the surrounding tissue from a blood artery or capillary in the skin or muscle below, resulting in an unusual black and blue bruise.

- The usual at-home treatments for a bruised knee include rest, ice, elevation, and, if necessary, over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medications like ibuprofen.

Abrasion

- An abrasion is another name for a tear.

- This happens when the skin comes into contact with a rough surface, such as asphalt or cement.

- A small abrasion can be healed at home since it just removes the skin’s outer layer or epidermis.

- Medical attention may be necessary for severe abrasions that involve blood and several layers of skin.

Laceration

- A laceration is a wound that tears or punctures skin as a result of a cut or pierces as well.

- Falling and landing on something sharp, like a nail, might cause a laceration.

- Similar to abrasions, lacerations can range in severity from very shallow, requiring medical attention, to small, with little to no blood.

Sprain

- A sprain can result from one or more knee ligaments being overextended.

- One kind of structure that connects two bones is called a ligament.

- A severe fall or getting hit by anything heavy or powerful, such as a football attack, can result in a sprained knee.

- Usually, you may treat your sprain and recover at home.

Speak with a doctor if;

- A lot of swelling is present.

- Terrible pain.

- You have extreme difficulty moving your knee.

Meniscus tear

- The meniscus is an element of flexible cartilage that fits between the femur and tibia and acts as a support for those two bones.

- Meniscus tears tend to happen after a hard fall, but they are also common in sports like football or basketball following a hard turn.

- Chronic pain and swelling may be signs that your torn meniscus needs to be medically repaired, even though some meniscus tears can be handled conservatively, meaning no surgery is necessary.

Tendon tear

The two main tendons in the knee are as follows;

- The tendon that connects the patella (kneecap) to the quadriceps muscle in the front of the thigh is known as the quadriceps tendon.

- The patellar tendon connects the base of the patella to the tibia (shinbone).

- A fall that lands awkwardly or a fall that impacts the front of the knee might result in either injury.

- Patellar tendon tears are the most frequent.

Torn ligament

Four primary ligaments in the knee unite the tibia and femur, or thighbone, allowing for side-to-side rotation as well as forward and backward motion.

- An anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)

- Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL)

- Medial collateral ligament (MCL)

- Lateral collateral ligament (LCL)

Signs and symptoms of knee injuries:

The location and degree of knee pain may vary depending on the underlying cause of the issue.

Sometimes, knee pain will be along with the following signs and symptoms;

- Popping or crunching sounds.

- Unable to extend the knee to its maximum range.

- Stiffness as well as swelling.

- Not having a full range of motion in the knee.

- Redness and warmth that is touch-sensitive.

Mechanical challenges:

A few examples of mechanical problems that can cause knee pain are as follows;

If there is damage or degeneration, an element of bone or cartilage can break off and float in the joint space. This may not be a problem unless the loose body limits the knee’s range of motion. That would make things like a pencil jammed in a door hinge.

The reason for this is that severe tightness in the iliotibial band, a solid band of tissue extending from the outside of your hip to the outside of your knee, pushes against the outside of your thighbone. Prolonged-distance runners and cyclists are especially susceptible to iliotibial band syndrome.

The patella, the triangle-shaped bone covering the front of the knee, slips out of place, usually to the outside, resulting in this. In certain cases, the dislocated kneecap may still be noticeable.

You can alter your gait to spare the sore joint if you have foot or hip pain. On the other hand, knee pain could result from this altered gait putting more strain on your knee.

Arthritis:

Knee pain is most commonly caused by osteoarthritis. Adults in their middle and later years are often impacted. Osteoarthritis may be caused by excessive joint stress, such as being overweight or experiencing recurrent injuries.

Types of arthritis:

- Gout: This type of arthritis comes on by crystals of uric acid building up in the joint. Gout may affect the knee, even though it usually affects the big toe.

- Osteoarthritis: Also known as degenerative arthritis, osteoarthritis is the most common type of arthritis. It is an age and use-related wear and tear condition caused by the degradation of knee cartilage.

- Rheumatoid arthritis: This autoimmune disease, which can affect almost any joint in the body, including the knees, is responsible for the most painful kind of arthritis. Though it may vary in severity and even flare up and disappear, rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic illness.

- Pseudogout arthritis: Pseudogout is often confused with gout and is caused by calcium-containing crystals that form in the joint fluid. The knee is the joint that is most frequently affected by pseudogout symptoms.

- Septic arthritis: Swelling, pain, and redness in your knee joint can sometimes be caused by an infection. Fever is a common symptom of septic arthritis, and pain rarely follows trauma. Septic arthritis has the potential to quickly cause deep damage to the knee cartilage. See your doctor right away if you experience knee pain in addition to any of the symptoms of septic arthritis.

Risk factors:

- Genetics and Family History

Some people are more likely to get osteoarthritis because it increases the risk of knee damage. Moreover, a less stable knee is experienced by those who are born with excess joint space.

If you have previously experienced a knee injury, your chances of getting another one rise.

- Particular athletic activities or fields:

Knee strain from sports is higher than from other sports. Basketball jumps and pivots, snow skiing (with its stiff ski boots and potential for falls), and running/jogging (which repeatedly pounds your knees) all raise the possibility of a knee injury. Jobs requiring repetitive knee strain, such as farming or construction, may also raise your risk.

Being overweight or obese puts additional strain on your knee joints, even during everyday activities like walking or stair climbing. Additionally, because of how quickly joint cartilage decreases, it raises the risk of developing osteoarthritis.

Just like when you play sports, kneeling or squatting a lot at work increases your chance of developing knee problems.

- Insufficient strength or flexibility in the muscles

People who have weaker muscles may be more likely to have accidents with their knees. Flexible muscles allow you to move through your full range of motion, while strong muscles protect and support your joints.

Diagnosis

During the physical examination, your doctor might;

- Look for obvious bruises, warmth, soreness, pain, and swelling on your knee.

- Take a range of motion measurement of your lower leg in different directions.

- Put pressure or tension on the knee joint to figure out how stable its structures are.

Imaging examinations:

In particular situations, your doctor might suggest tests such as;

- X-ray: An X-ray may be the first test your doctor suggests to check for bone fractures and joint damage.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan: By combining X-rays from different angles, CT scanners create cross-sectional images of your inside body. CT scans are useful for detecting small bone fractures and issues. With a particular kind of CT scan, gout can be correctly diagnosed even in situations where there is no joint inflammation.

- Ultrasound: This method creates real-time images of the soft tissue structures in and around your knee using sound waves. During the ultrasonography, your doctor might want to move your knee around to check for any specific issues.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): Using radio waves and a powerful magnet, an MRI creates three-dimensional images of the inside of your knee. When checking damage to soft tissues like muscles, tendons, ligaments, and cartilage, this test is especially helpful.

When to see a doctor for advice:

You must get medical advice from a doctor,

- Hearing a “pop” sound during the fall, since this is typically an indication of a torn ligament.

- Another common symptom of a ruptured knee ligament is a feeling of instability, buckling, or giving way.

- You cannot bend your knees and walk.

- Your knee is not completely flexible.

- It may be a sign of structural damage to the knee if you are unable to bear weight on it.

- Have edema in the knees that is noticeable.

- Find a noticeable deformity in your leg or knee.

- Your knee may feel warm to the touch following a fall. This may be a sign of inflammation resulting from a muscle or tendon tear.

- Warmth can also be a sign of an infection or bursitis.

- Experience acute knee pain related to an accident.

- If the bleeding from a cut or scrape doesn’t stop after a few minutes, you might need to visit a doctor.

Treatment:

Initial medical care should be managed within 48 to 72 hours following a knee injury.

Here are some guidelines for administering basic medical care for a knee injury;

- Quit your activity right away.

- Stop from “working beyond” your pain.

- Give the joint some time to rest first.

- Ice packs should be applied to pain, edema, and internal bleeding for fifteen minutes each day for a few hours.

- Start by applying strong knee tape to the lower leg.

- Lift the injured leg.

- Stay out of heating the joint.

- Avoid alcohol as it exacerbates bleeding and edema.

- Refrain from rubbing the joint as this could make the swelling and bleeding worse.

In-home care:

R.I.C.E. has a major healing effect on knee injuries. Your injury will determine your course of action. Most mild to moderate issues resolve themselves.

The simplest method for expediting the healing process is to;

- Let your knee rest.

- Take a few days off from any physically demanding activities.

- Use ice to relieve pain and swelling.

- Every three to four hours, give it a quarter to a half hour. Continue doing this until the pain slows down, which should take two to three days.

- Apply force to your knee. To wrap the joint, use straps, long sleeves, or an elastic bandage. It will either encourage or lessen edema.

- Raise your knee and put a pillow under your heel to reduce swelling when you sit or lie down.

Medicine treatment:

- Put painkillers to use.

- It is possible to reduce pain and swelling by taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like naproxen or ibuprofen.

- These medications have the potential to cause side effects, so you should only use them occasionally unless directed otherwise by your doctor.

Injections:

In certain situations, your doctor may recommend injecting medications or additional components directly into your joint.

Take, for instance,

- Corticosteroids: A corticosteroid injection into your knee joint may help lessen the symptoms of an outbreak and offer temporary pain relief. Not every time do these injections function as planned.

- Hyaluronic acid: You can receive an injection of hyaluronic acid, a thick fluid that resembles the fluid that lubricates joints naturally, to increase the range of motion and reduce pain. Relief after a single or series of shots may last up to six months, even though conflicting results in research on the effectiveness of this treatment.

- Platelet-rich plasma (PRP): PRP appears to reduce inflammation and promote healing because of its high concentration of growth factors. Further research is necessary, but some patients with osteoarthritis may benefit from PRP, according to some research.

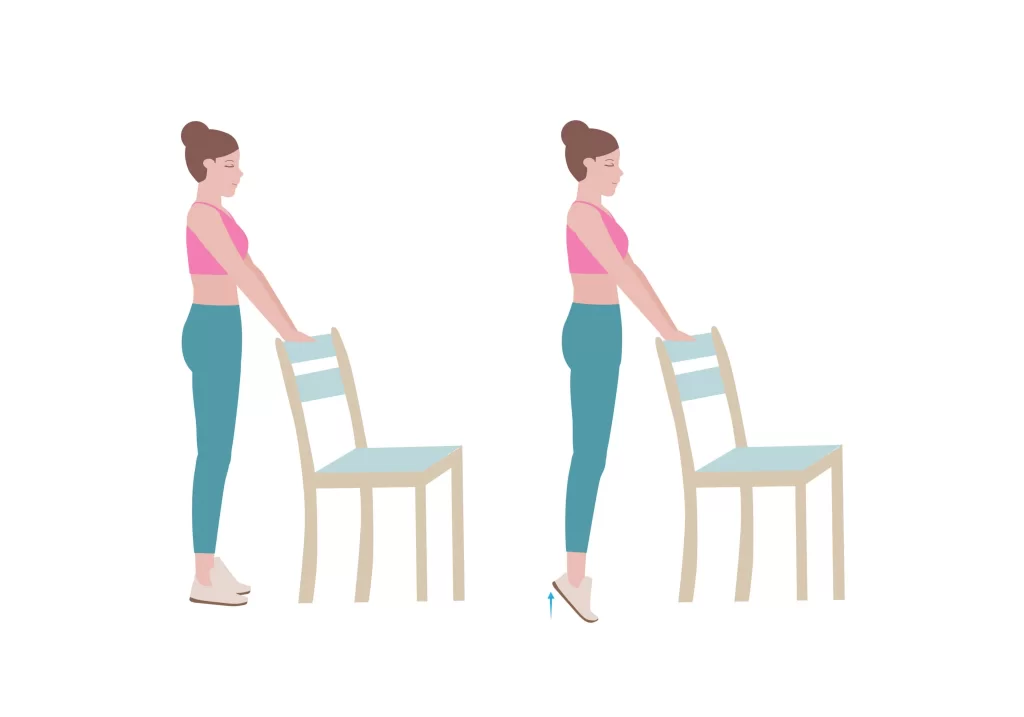

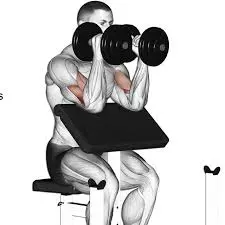

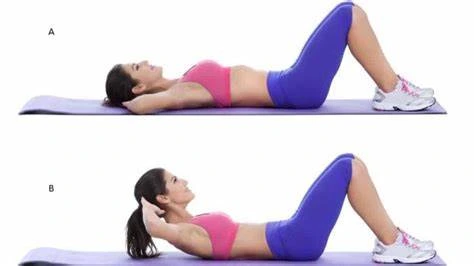

Physical Therapy treatment:

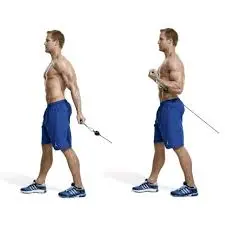

You can increase the stability of your knee by strengthening the surrounding muscles. Depending on the specific ailment that is causing the pain, your physician may recommend physical therapy or different strengthening exercises.

If you play a sport or engage in physical activity, you may need to perform exercises to improve movement patterns that could be damaging to your knees and to establish proper technique during your activity. It’s also essential to perform exercises that improve your flexibility and balance.

Arch supports, which sometimes feature wedges on one side of the heel, can help relieve pressure on the side of the knee affected by osteoarthritis. Certain brace types can help protect the knee joint in specific conditions.

Surgical treatment:

For many fractures and injuries close to the knee, Often, surgery is necessary to fully restore leg function. In certain situations during arthroscopic surgery, like multiple anterior cruciate ligament tears, small instruments and tiny incisions may be used.

On the other hand, fractures often require open surgery, which involves a larger incision and allows your surgeon easier access to the injured structures.

If you have an injury that may require surgery, you usually don’t have to have it done right away. Consider the most important things and the advantages and disadvantages of nonsurgical rehabilitation and surgical reconstruction before making a decision.

If you decide to have surgery, you may be able to choose from the following options:

- Arthroscopic surgery: Your doctor may be able to examine and repair joint damage around your knee using a fiber-optic camera and long, narrow tools inserted through a few tiny incisions, depending on the type of injury you have. Arthroscopy can be used to replace torn ligaments, repair or replace damaged cartilage, and, if your knee is locking, remove any loose bodies from the joint.

- Partial knee replacement surgery: Your surgeon will replace only the damaged portion of your knee with metal and plastic components. Because this procedure typically involves making small incisions, you should recover from it more quickly than from surgery to replace your entire knee.

- A total knee replacement involves the surgical removal of your kneecap, shinbone, and thighbone as well as any damaged bone or cartilage. An artificial joint made of premium plastics, metal alloys, and polymers is placed in their place.

- Osteotomy: By removing bone from the shin or thighbone, this procedure intends to improve knee alignment and reduce pain associated with arthritis. This surgery may allow you to delay or even prevent a total knee replacement.

What is the treatment for knee pain following a fall?

The standard treatments for knee injuries caused by falls include rest and, if necessary, bracing the injured joint to maintain stability. In most cases, anti-inflammatory painkillers such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) may be helpful.

Many times, small knee injuries can be handled at home. However, it’s imperative to see a doctor if symptoms worsen or if the pain gets worse by any of the following;

- A significant amount of joint swelling.

- An inability to keep up weight.

- Additional signs of ligament or tendon damage.

- If the damage is severe, surgery might be necessary to relieve pain and restore function.

How long does it take for an injury to heal on the knee?

The duration of healing for a knee injury depends on its type and severity. A lengthier recovery time may be necessary if the injury involves surgery and/or physical treatment.

- A straightforward strain or sprain could last for a week or two.

- It can take one to three months for more serious injuries that require arthroscopic surgery to heal.

- knee injury so bad that it takes a year to recover.

Following your doctor’s instructions for immobilization, rest, staying off your feet, and avoiding strenuous exercise that might worsen the injuries could speed up your recovery.

Physical therapy is another way to speed up the healing process. Following your physical therapist’s instructions is important to ensure that you are doing the exercises correctly and getting the best results.

Non-surgical chronic knee problems could come up frequently. Anti-inflammatory medications, physical therapy, and cortisone injections can all provide short-term relief.

Prevention:

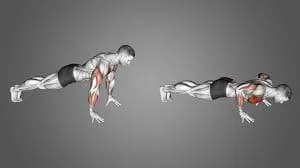

Although preventing knee injuries isn’t always possible, some things can be taken to lower the risk. For example, people who run or play sports should wear suitable footwear and safety equipment.

In cases of iliotibial band syndrome or overuse injuries, one may want to consider reducing their running mileage.

Several exercises are also used to strengthen the muscles in the smaller legs, which reduces the risk of injury. Last but not least, stretching can help avoid knee injuries both before and after exercise.

Eating a healthy diet is also important, especially for athletes. Protein, calcium, and vitamin D are necessary for the upkeep of strong bones, muscles, and ligaments.

Although it’s not always possible to avoid knee pain, the following methods can help stop injuries and degeneration of the joint;

- Avoid gaining any additional body fat.

- One of the finest things you can do for your knees is to keep up a healthy weight. Your risk of developing osteoarthritis and other disorders rises with each extra pound you put on.

- Get dressed up to participate in your sport.

- To prepare your muscles for the demands of playing sports, spend some time working them out.

- Improve your ability to perform.

- Ensure that your sports or activity-specific movement patterns and skills are at their best.

- Getting professional advice can be very helpful.

- Develop your strength without sacrificing your flexibility.

- Weak muscles are one of the primary causes of knee injuries.

- You will benefit from strengthening the quadriceps and hamstrings, the muscles on the front and back of your thighs that support your knees.

- Engage in suitable physical activities.

- If you have osteoarthritis, chronic knee pain, or a history of injuries, you may need to adjust your exercise routine. At least a few days a week, think about moving to low-impact activities like swimming, water aerobics, or other comparable options.

When Will My Knee Feel Better Again?

It also depends on what nature of injury. Furthermore, some people naturally heal faster than others. Find out from your doctor if there’s anything you can do to keep your knee pain from getting worse while you recover. Be patient in everything you do.

You should wait to resume your regular exercise therapy until you experience these symptoms;

- Your knee does not hurt when you bend or straighten it.

- There is no pain in your knee when you run, walk, jump, or sprint.

- The strength of the injured knee is equal to that of the uninjured knee.

Prognosis:

- The prognosis for a knee injury depends on the type and severity of the damage.

- With conservative care, most mild knee injuries like strains and mild sprains heal on their own. The prognosis is good for these kinds of injuries.

- If damage to the ligaments or cartilage results in the knee malfunctioning or becoming unstable, surgery might be required.

- These injuries usually heal well with surgery, allowing patients to eventually regain their full or nearly full range of motion in their knees.

Summary:

Knee pain affects people of all ages regularly. An injury like a torn cartilage or ruptured ligament may be the source of your knee pain. Diseases such as gout, arthritis, and infections can also cause knee pain. Numerous forces, strong knee twists, or high impacts from auto accidents can result in these injuries. It reduces shock and provides a smooth, moving surface for joint mobility.

An injury like a torn cartilage or burst ligament could be the cause of your knee pain. Other conditions that can aggravate the knee include infections, gout, and arthritis. These injuries can result from a variety of forces, strong knee twists, falls, or high impacts from auto accidents. Sprains, tears, dislocations, and fractures are among the common injuries to the knee.

Self-care techniques are an effective treatment for many types of moderate knee pain. Physical therapy and knee braces are more choices for pain relief. In addition to pain, you should see a doctor if you have severe swelling, a buckling or giving way sensation, or difficulty bearing weight on the injured knee. On the other hand, there are situations in which knee surgery is required.

While a knee brace and rest are often enough to treat minor injuries to the knee, surgical intervention may be required if a ligament or tendon is torn. Following a knee injury, you must attend any recommended physical therapy sessions to ensure a full recovery. You’ll get your knee’s strength and range of motion back, lessen pain, and heal more quickly if you do this.

FAQ:

Which three types of knee injuries are the most common?

The most common injuries to the knee include sprains, fractures, dislocations, and tears of the soft tissues (meniscus and ligaments). Many times, injuries affect multiple knee structures. When a knee injury occurs, pain and swelling are the most common symptoms. Furthermore, the knee may lock or catch.

What is the process to evaluate the level of a knee injury?

You can’t put weight on your knee.

You’re in excruciating pain.

Suddenly, your knee developed swelling.

Do knee injuries recover naturally?

Even if small injuries to the knee heal on their own, a doctor or physical therapist should evaluate and determine the problem. For chronic knee pain, medical care is necessary. Any knee injury that receives prompt medical attention raises the likelihood of complete recovery.

How much time does it take to recover from a knee injury?

The amount of time it takes for a knee injury to heal depends on many factors. Common knee injuries may take anywhere from two weeks to nine months to fully heal. Certain wounds heal fast and don’t need much medical care. Surgery, physical therapy, or a lengthy recovery period may be necessary for other injuries.

If someone has a knee injury, should they walk?

Try to walk normally by putting your heel down first if you aren’t instructed to put any weight through your knee. While it’s important to keep moving as much as possible, overdoing it too soon after your accident could make the swelling and pain worse.

Can heat be applied to a knee injury?

A single useful method for relieving joint stiffness and tightness is the application of heat.

Should I put a bandage on my knee if it hurts?

For support, wrap your knee or use a knee brace. This is known as compression. Enough tightness to fit, but not too tight. Knee swelling ought to be managed with the right compression.

Which exercises should you avoid doing if you’re injured in your knee?

Exercises that put a lot of strain on the knees, such as deep squats, running, and jumping, should be avoided if possible. Select more gentle workouts that will keep your knees from getting any worse while still keeping you in shape.

What is the ideal sleeping posture for pain in the knees?

If you have knee pain, you may need to elevate your leg and knee while you sleep. If so, sleeping on your back is the best position. Put a pillow under both legs to elevate one’s knee above the level of the heart. If edema is present in the knees, the elevation can help reduce it.

Do I need to put some ice on my knee?

The freezing temperature reduces blood vessel enlargement and inflammation in the knees. It also numbs the area, which could minimize pain. When applying ice to a knee injury, it is important to cover the area with a towel or piece of cloth to avoid skin contact.

What is causing my knee pain when I bend it?

Many people have knee pain when bending over, which might have a variety of underlying causes. Meniscus tears, bursitis, strained ligaments, osteoarthritis, and tendinitis are a few of the most common reasons. Joint infections or bone fractures can also cause knee pain.

Why is my knee injury not healing?

You may have incorrectly estimated the severity of your knee injury or not given it enough time to heal and relax if it doesn’t appear to be healing. Going back too soon after a knee injury might worsen the pain and damage to the tissue. Moderate soft-tissue injuries typically take two weeks or longer to heal.

I have a knee injury; is it still safe to exercise?

Exercise shouldn’t exacerbate your knee pain. However, when you practice new exercises, you may experience some temporary soreness in your muscles as your body gets used to the new movements.

How long does a serious knee injury take to heal?

The time it takes to heal from a knee injury can vary depending on several factors. Less serious wounds may heal on their own without requiring a lot of medical attention. Surgery, physical treatment, and a lengthier recovery period may be necessary for some injuries.

Which symptoms are associated with knee damage?

There is a deformity or curve in your knee. You can’t flex your knee fully and worry to extend it fully. High levels of swelling, redness, or warmth are felt near the knee. You experience pain in your calves, edema, tingling, numbness, or bluish pigmentation below the sore knee.

How much knee injury can you tolerate?

Your knee condition won’t get worse while you walk. Whenever you can, try to walk as simply as possible, with your heel down. Excessive weight bearing in the early stages following an injury may increase pain and swelling. You might be given crutches that can help you with this for only a short amount of time.

Is it possible to avoid experiencing knee pain?

It’s possible.

Stretching strengthens the muscles surrounding your knees, which supports and relieves pressure and strain on your joints. If you do not like stretching, especially before working out, you can prevent injury to your knees by increasing the intensity of your workout rather than jumping right into it. Strengthening your thighs, calves, and the front and keep of your thighs in addition to reducing weight might help prevent knee problems.

Is it better to walk or rest when experiencing knee pain?

If you have arthritis or a minor knee injury, treating the pain when it returns is essential. Pain should be treated as soon as it manifests itself to help manage it. The “RICE” protocol which includes rest, ice, compression, and elevation will help you relieve your knee pain.

Why are injuries happening so frequently?

Recurrent injuries can occur when you overuse the same muscles without giving them enough time to heal. Simply put, using weak muscles longer raises the chance of reinjury. This is simple body mechanics.

What kind of substance hurts the knees?

The location of knee pain may help identify its cause. Pain at the front of the knee can be caused by bursitis, arthritis, or chondromalacia patella, which is a weakening of the patella cartilage. Pain on the outside of the knee is often associated with collateral ligament injuries, meniscus tears, and arthritis.

What kind of treatment is there for knee pain caused by inactivity?

Stretching and strengthening exercises performed at home, however, can help with most knee pains. To prevent the pain that comes with sitting all day, take a walk and stretch every 30 to 60 minutes. Stretching and strengthening exercises done in the right order can help reduce pain by improving joint function and movement.

Can someone with a knee injury bend their knee?

Most knee injuries cause pain. “Giving way,” “locking,” or experiencing weakness in the knee are additional signs of a knee injury. A person’s ability to fully bend or straighten their knee may be limited by a knee injury. The injured knee may have swelling or bruises.

References:

- Injury to the Knee. (n.d.). Johns Hopkins Medicine. Fractures are among the common injuries to the knee, resulting from trauma and injury sustained in a high-impact fall.

- OrthoInfo – AAOS – Common Knee Injuries (n.d.). Common knee injuries are listed under diseases and conditions at https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en.

- “Mayo Clinic: Knee Pain Symptoms and Causes.” www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/knee-pain/symptoms-causes/syc-20350849.html, Mayo Clinic, January 25, 2023.

- Knee injuries, no date. Causes, Symptoms, and Treatments | Stretching of muscles and tendons is one of the common knee injuries, according to Health direct (https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/knee-injuries#:~).

- orthoinfo.aaos.org Conditions–diseases %2Fen%2F2Fcommon-knee-injuries%2F&psig=AOvVaw0fd-e_BwevS2S5O4FPVDoP&ust=1706529350280000&source=images &cd=vfe & opi=89978449&ved=0CBMQjRxqFwoTCJD0h8CDgIQDFQAAAAAdAAAAABAD.

- El-Feky, Mostafa, and Andrew Dixon. “Entrapment of the Popliteal Artery.” 15 Apr. 2010, Radiopaedia.org, https://doi.org/10.53347/rid-9410.

- Jenna Fletcher. Ten Typical Knee Injuries and How to Treat Them. www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/319324, September 9, 2017.

- Knee pain causes and treatments: a comprehensive guide from WebMD. Why Am I Experiencing Knee Pain? (December 22, 2016). http://www.webmd.com/pain-management/knee-pain/knee-pain-causes is the WebMD website.

- Blauvelt, C. T., and Nelson, F. R. (2015, January 1). Musculoskeletal Conditions and Associated Words. eBooks from Elsevier. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-22158-0.00002-0.

- n.d. Knee injuries. Channel for Better Health. Knee injuries can be found at https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments

- Jim Roland. “The Eight Most frequent Knee Injuries related with Falls.” The eight most common knee injuries experienced from falls appeared on www.healthline.com/health on September 22, 2020.Wellline.

- J. P. C. D. Facoep (2023, July 13).Meniscus tears and knee injuries: symptoms, interventions, and recovery. Knee injuries and meniscus tears. MedicineNet.com. https://www.medicinenet.com/article.htm.

- A. A. Dutton (2023, April 21). Ten Typical Knee Injuries, Particularly for Athletes. Singapore’s Dr. Dutton Orthopaedic & Sports Medicine Clinic. knee injuries at https://www.drandrewdutton.com/blog/.

- Spine, N. October 19, 2023. These Are The Top 9 Knee Injuries. NJ Orthopedic & Spine. The nine most common knee injuries are listed at https://www.njspineandortho.com/.

- In n.d., Willigmann, A. Rothman Orthopaedic Institute: The Top 5 Most Common Knee Injuries. The five most common knee injuries are listed at https://rothmanortho.com/stories/blog/.

- Knee Injury Types and Their Reasons. (For the time being). Visit https://www.osmifw.com/orthopedic-diseases-disorders/knee-injuries-disorders/ to learn about the types and causes of common knee injuries and problems. The in-text citation is Common Knee Injuries: Types and Causes.