Vestibulocochlear nerve

Introduction

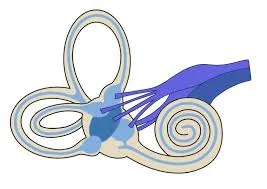

The vestibulocochlear nerve is also called cranial nerve eight (CN VIII). The vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII) connects the vestibular and cochlear nerves. It is situated within the internal auditory meatus (internal auditory canal).

The cochlear nerve controls hearing, while the vestibular nerve controls balance and eye movements.

CN VIII injuries are caused by pathological processes or injuries that commonly affect the cerebellopontine angle (CPA), internal auditory canal (IAC), or inner ear. Vertigo, nystagmus, tinnitus, and sensorineural hearing loss are some of the symptoms that may occur.

The vestibulocochlear nerve is a nerve in the human ear that serves the organs of equilibrium and hearing. It consists of two anatomically and functionally different parts: the cochlear nerve, which travels to the hearing organ, and the vestibular nerve, which is sent to the organ of balance.

The cochlear nerve fibres terminate at the bases of the inner and outer hair cells of the organ of Corti and begin in groups of nerve cells referred to as the dorsal and ventral cochlear nuclei, which are situated at the base of the brain where the medulla oblongata and pons converge.

The vestibular portion of the vestibulocochlear nerve is formed by a group of nerve cells known as the vestibular ganglion in the internal acoustic meatus, a channel in the temporal bone that runs through the facial and auditory nerves as well as some blood vessels. This nerve’s sensory endings are located in the semicircular canal, as well as the utricle and saccule, which are inner ear structures that provide the sensation of balance.

Anatomical Course of Vestibulocochlear nerve

The vestibular and cochlear portions of the vestibulocochlear nerve are functionally distinct and thus originate from different nuclei in the brain.

The vestibular component is derived from the vestibular nuclei complex in the pons and medulla of the brainstem.

The cochlear component is formed by the ventral and dorsal cochlear nuclei located in the medulla.

The vestibulocochlear nerve is formed when both sets of fibres combine in the pons. The nerve exits the cranium through the temporal bone’s internal acoustic meatus after emerging from the brain at the cerebellopontine angle.

The vestibulocochlear nerve splits at the distal end of the internal acoustic meatus, resulting in the vestibular and cochlear nerves. The vestibular nerve innervates the vestibular system of the inner ear, which detects balance. The cochlear nerve travels to the inner ear’s cochlea, where it forms the spiral ganglia responsible for hearing.

Function of Vestibulocochlear nerve

The vestibulocochlear nerve is unique in that it is composed primarily of bipolar neurons. It regulates the cochlear nerve, which is responsible for hearing, and the vestibular nerve, which is responsible for balance.

Hearing

The cochlea detects both the magnitude and frequency of sound waves. The inner hair cells of the organ of Corti activate ion channels in response to basilar membrane vibrations. Action potentials originate in the spiral ganglia, which house the cochlear nerve’s neuron cell bodies.

The magnitude of the sound determines how much the membrane vibrates, and thus how frequently action potentials are triggered. Louder sounds cause the basilar membrane to vibrate more, increasing the frequency with which action potentials are transmitted from the spiral ganglia, and vice versa. The position of activated inner hair cells along the basilar membrane determines the sound frequency.

Equilibrium (balance)

The vestibular apparatus senses changes in the head’s position to gravity. The vestibular hair cells are found in the otolith organs (the utricle and saccule), which detect linear head movements, and in the three semicircular canals, which detect rotational head movements. The vestibular ganglion, situated in the exterior region of the internal acoustic meatus, houses the vestibular nerve cell bodies.

The vestibulo-ocular reflex and balance are coordinated based on information about the head’s position. The vestibule-ocular reflex (sometimes called the oculocephalic reflex) maintains pictures on the retina as the head rotates by moving the eyes in the opposite direction. It can be demonstrated by keeping one finger still at a comfortable distance before you and twisting your head from side to side while keeping your attention on the finger.

Embryology

Cranial sensory organs in vertebrates develop from cranial placodes, which are thickenings in the ectoderm. The vestibular and cochlear apparatuses emerge from the otic placode, which forms around the third week of gestation. During the fourth week, the otic placode invades and forms the otic vesicle. This otic vesicle gives rise to the cochlear (Spiral) and vestibular (Scarpa) ganglia, which then form peripheral and central projections of the auditory and vestibular pathways, respectively.

Associated Conditions of Vestibulocochlear nerve

Vestibulocochlear nerve disorders can impair balance and hearing. Otologists and neurotologists frequently treat vestibulocochlear nerve disorders.

Vestibular Neuritis & Labyrinthitis

Vestibular neuritis is an inner ear disorder that affects the vestibular portion of the vestibulocochlear nerve, which controls equilibrium. When this part of the nerve swells, it disrupts the information it normally sends to the brain about balance.

Labyrinthitis, like vestibular neuritis, affects both the vestibular and cochlear nerves. Both conditions typically appear suddenly.

Acoustic Neuroma

Acoustic neuroma is a non-cancerous tumour that develops on the vestibulocochlear nerve. Tumours can develop on one or both nerves, with unilateral acoustic neuromas (which affect only one ear) being more common.

People who have received neck or face radiation or have neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) are more likely to develop an acoustic neuroma.

Symptoms

- Sudden onset, severe vertigo

- Imbalance

- Nausea and vomiting.

- difficulty concentrating

- Hearing loss (Labyrinthitis only)

- Single-sided hearing loss

- Headaches

- Clumsiness and confusion.

- A sensation of fullness in the ears

- Tinnitus

- Dizziness and balance issues.

- Facial numbness.

Symptoms usually resolve within a few days. Some people have had dizziness and balance problems for months. These disorders could be caused by a viral or bacterial infection.

Examination of Vestibulocochlear nerve

Hearing testing

Initial hearing testing consists of rubbing the fingers against one ear while occluding the other, then repeating for the other ear. This can also be accomplished by whispering into one ear while closing the other and repeating on the opposite side. Take note of any asymmetry in response or hearing. If hearing loss is suspected, further evaluation with the Rinne and Weber tests is recommended; these tests aid in distinguishing between conductive and sensorineural hearing loss.

Rinne test

The Rinne test involves placing a vibrating 512-hertz tuning fork on the mastoid process and moving it to just outside the ear once the sound is no longer audible. In a normal (positive) Rinne test, air conduction exceeds bone conduction. In an abnormal (negative) Rinne test, bone conduction exceeds air conduction in the affected ear. A patient with profound sensorineural hearing loss may not hear anything when the tuning fork is placed on the mastoid process or near the external auditory canal. Sound travels through the skull to the opposite ear, and the patient may be unable to determine which ear heard it.

In this case, it appears that bone conduction is greater than air conduction, but the ear is completely non-functional. This is known as a false negative Rinne test. A Weber test distinguishes between a negative and a false negative test.

Weber test

The Weber test involves placing a vibrating 512-hertz tuning fork in the centre of the forehead. Sound is louder in, or “lateralizes to,” the conductive hearing loss ear or the opposite ear with sensorineural hearing loss. Referral testing is necessary for patients with sensorineural hearing loss, as they can be further classified as sensory or neural based on brainstem auditory evoked responses (BSAERs).

Vestibular testing

To evaluate vestibular function, look for nystagmus and record the direction, duration, and trigger. When a patient is experiencing vertigo during an examination, more thorough testing is necessary to differentiate between central and peripheral sources. By preventing visual fixation, nystagmus can be lessened. Frenzel lenses or glasses with a +30 diopter can do this. The head thrust manoeuvre is used to test for acute vestibular syndrome, while the Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre tests for positional vertigo.

The head thrust manoeuvre

The head thrust manoeuvre involves holding the sitting patient’s head while focusing on an object, such as the examiner’s nose, and quickly turning the patient’s head 20 degrees to the right or left. If the eyes are fixed on the examiner’s nose, this is normal. A temporary deviation away from an object followed by a corrective saccade that returns the eyes to it indicates a peripheral source of nystagmus, such as vestibular neuronitis.

The Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre

The Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre involves quickly lowering the patient to a supine position, extending the head 45 degrees below the table and turning 45 degrees to one side. Take note of the direction and duration of the nystagmus, and check for vertigo. Raise the patient back to an upright position and repeat the manoeuvre with the head turned to the opposite side.

Nystagmus with a latency period of five to ten seconds, which is vertical when the eyes are turned away from the affected ear and rotary when the eyes face the affected ear, is pathognomonic for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. This response also diminishes with subsequent testing. Positional nystagmus caused by central nervous system dysfunction has no latency period and does not resolve with additional testing.

Treatment

Treatment for vestibulocochlear nerve disorders typically consists of managing symptoms until they resolve. Sometimes additional intervention, such as medication or surgery, is required.

Medication is used to treat nausea and dizziness associated with vestibular neuritis and labyrinthitis. These medications should not be taken for longer than a few days.

Some medications can alleviate nausea and vertigo. Among them are

- metronidine (Antivert) and diphenhydramine (Bendadryl)

- Diazepam (Valium) and Lorazepam (Ativan)

Antivirals may be prescribed if a virus is thought to be present. Steroids are also used on occasion, though their benefits are debatable.

Balance rehabilitation may be recommended if symptoms last more than a few weeks. Rehabilitation exercises include body posture, balance, vision, and head-turning. Most people with vestibular neuritis and labyrinthitis recover completely.

Acoustic neuroma treatment is determined by the size of the tumour as well as the patient’s overall health. Radiation, surgery, and watchful waiting are available as treatments.

Surgical removal is performed via craniotomy, which is the surgical removal of a portion of the skull to gain access to the brain. The “keyhole” craniotomy is the least invasive surgery option. A keyhole craniotomy involves making a small incision behind the ear to access the affected nerve.

Translabyrinthine craniotomy is a more invasive surgery that may be used for larger tumours or when hearing is already impaired. To access the tumour, a surgeon makes an incision in the scalp behind the ear and removes the mastoid bone as well as a portion of the inner ear bone. This surgery provides complete hearing.

Following treatment, cochlear implants or hearing aids may be beneficial. Plastic surgery can help restore facial function if surgery damages facial nerves.

Summary

The vestibulocochlear nerve, also known as cranial nerve eight (CN VIII), connects the vestibular and cochlear nerves within the internal auditory meatus. It regulates body balance and eye movements, while the cochlear nerve controls hearing. CN VIII injuries can cause symptoms like vertigo, nystagmus, tinnitus, and sensorineural hearing loss.

The vestibular ganglion in the internal acoustic meatus, a tube in the temporal bone that passes through several blood vessels, facial and auditory nerves, forms the vestibular nerve. The vestibular nerve is unique in its primarily bipolar nature, regulating the cochlear nerve, responsible for hearing, and the vestibular nerve, responsible for balance. Associated conditions of CN VIII include vestibular neuritis and labyrinthitis, which affect the vestibular portion of the nerve, disrupting the information it normally sends to the brain about balance. Acoustic neuroma can also develop on the vestibulocochlear nerve.

Vestibulocochlear nerve disorders can be diagnosed through hearing testing, vestibular testing, and acoustic neuroma treatment. Hearing testing involves rubbing fingers against one ear while occluding the other, while vestibular testing evaluates vestibular function by looking for nystagmus.

Treatment typically consists of managing symptoms until they resolve, with additional intervention, such as medication or surgery, if necessary. Medication can alleviate nausea and dizziness associated with vestibular neuritis and labyrinthitis, while antiviral drugs and steroids may be prescribed if a virus is suspected. Balance rehabilitation may be recommended for those with symptoms lasting more than a few weeks. Acoustic neuroma treatment depends on the size of the tumour and the patient’s overall health.

FAQs

What is the definition of vestibulocochlear nerve weakness?

Vestibular neuritis is a condition that affects the vestibulocochlear nerve in your inner ear. This nerve connects your inner ear and brain, transmitting information about your balance and head position. When this nerve becomes inflamed or swollen, it disrupts how your brain processes information.

What are some fascinating details about the vestibulocochlear nerve?

The vestibulocochlear nerve serves solely for sensory purposes. It has no motor functions. It transmits sound and equilibrium information from the inner ear to the brain. Soundwaves are detected by the cochlea, which is located in the inner ear and is the origin of the cochlear nerve.

Is vestibular cochlear function sensory or motor?

The vestibulocochlear nerve (eighth cranial nerve) is sensory. It consists of two nerves: the cochlear, which transmits sound, and the vestibular, which controls balance.

What is the primary function of the vestibulocochlear nerve?

The vestibulocochlear nerve is the 8th cranial nerve. The vestibular parts are involved in balance, posture, and spatial perception, whereas the cochlear branch is in charge of the special sense of hearing.

Are there two vestibulocochlear nerves?

The vestibular and cochlear nerves, collectively referred to as cranial nerve eight (CN VIII), make up the vestibulocochlear nerve. The brainstem contains distinct nuclei for each nerve. The vestibular nerve controls body balance and eye movements, whereas the cochlear nerve controls hearing.

References:

- Reese, V., Das, J. M., & Khalili, Y. A. (2023, May 6). Cranial Nerve Testing. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585066/

- The Vestibulocochlear Nerve (CN VIII) – Balance – Hearing – TeachMeAnatomy. (2023, August 11). TeachMeAnatomy. https://teachmeanatomy.info/head/cranial-nerves/vestibulocochlear/

- Bordoni, B., Mankowski, N. L., & Daly, D. T. (2023, May 22). Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 8 (Vestibulocochlear). StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537359/

- Vestibulocochlear nerve | Auditory, Hearing & Balance. (1998, July 20). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/vestibulocochlear-nerve

- The Vestibulocochlear Nerve (CN VIII). (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/The_Vestibulocochlear_Nerve_(CN_VIII)

- Valeii, K. (2023, August 21). Anatomy of the Vestibulocochlear Nerve. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/vestibulocochlear-nerve-5095249

2 Comments