The femoral neck fracture is a common injury primarily affecting elderly individuals, often resulting from low-energy trauma such as a fall from standing height. This fracture occurs in the proximal portion of the femur, where the femoral head connects to the shaft of the bone.

The incidence of femoral neck fractures is increasing globally, attributable to an aging population and rising life expectancy.

Introduction

One of the most common fractures that orthopedic trauma teams and emergency departments see is hip fractures. There is no difference between a “neck of femur fracture” and a “hip fracture.” A proximal femur fracture that occurs between the femoral head and five centimeters distal to the lesser trochanter is described by both names.

A broken hip, or Femoral Neck Fracture, is a dangerous injury, particularly in elderly adults. It might potentially change someone’s life and perhaps pose a threat to others. It happens when there is a break in the upper portion of the femur, or leg bone, directly below the ball and socket joint.

Elderly patients are more likely to suffer from neck of femur fractures (NOF), which are caused by a reduction in bone mineral density and an unsteady gait. The elderly female osteoporotic patient is the most vulnerable.

More than 90% of proximal femur fractures are femoral neck and peri-trochanteric fractures, which are equally common.

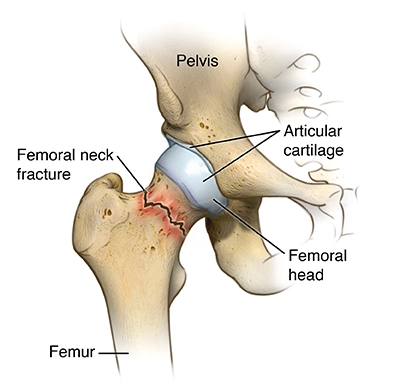

The femoral neck is the most common site of hip fractures. Where your upper leg and pelvis meet is called the hip, which is a ball and socket joint. The femoral head is located at the top of your thigh bone, or femur. The “ball” that is seated in the socket is this one. The femoral head is directly below the femoral neck.

Intracapsular fractures are those of the femoral neck. The fluid that nourishes and lubricates the hip joint is found inside the capsule. Based on where the fracture occurs along the femoral neck, fractures in this region are classified as follows:

Blood vessels may be torn by a femoral neck fracture, which would stop the femoral head’s blood flow. A process known as avascular necrosis will cause the bone tissue to deteriorate and eventually collapse if the blood supply to the femoral head is cut off. Broken bones that happen in areas where blood flow is unhindered are more likely to mend.

Because of these factors, the course of treatment for an aged patient with a displaced femur fracture will vary depending on the break’s position and the blood supply’s quality.

The accepted treatment protocol for a displaced fracture with disruption of the blood supply is femoral head replacement (hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty). In the event that there is no displacement, the fracture may be surgically stabilized with screws or other hardware. Still, there’s a chance that something will happen to the blood supply.

Anatomy of Femoral Neck Fracture

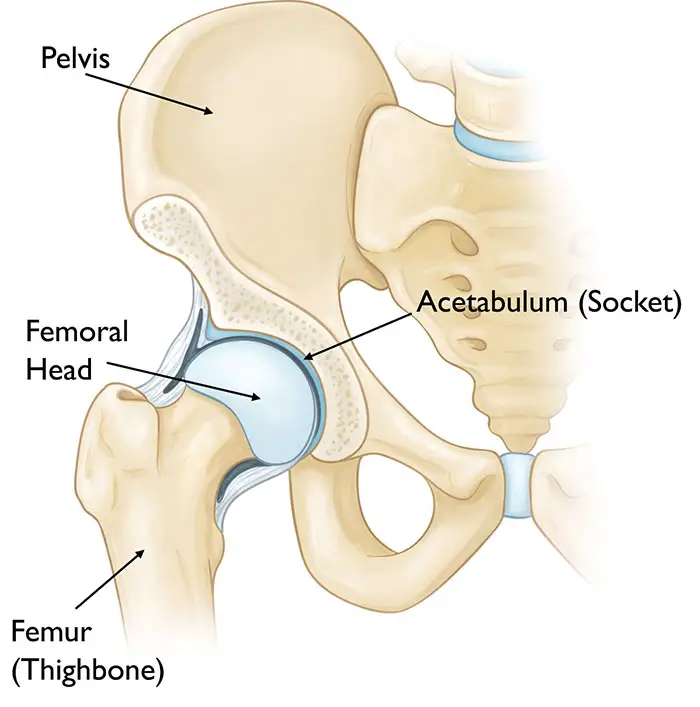

The hip joint consists of a ball and socket joint. The top portion of the thighbone, or the head of the femur, is the ball. The acetabulum is the name of the socket. The acetabulum is one part of the pelvic bone. The rounded shape of the femoral head accommodates it.

Hip Capsule

The transverse acetabular ligament and the acetabulum’s edge are where the hip capsule is proximally joined. Distally, to the femoral neck (1/2 inch from the trochanteric crest), to the bases of the greater and lesser trochanters, and to the intertrochanteric line. There are the retinal vessels, which are important for the blood supply to the femoral head.

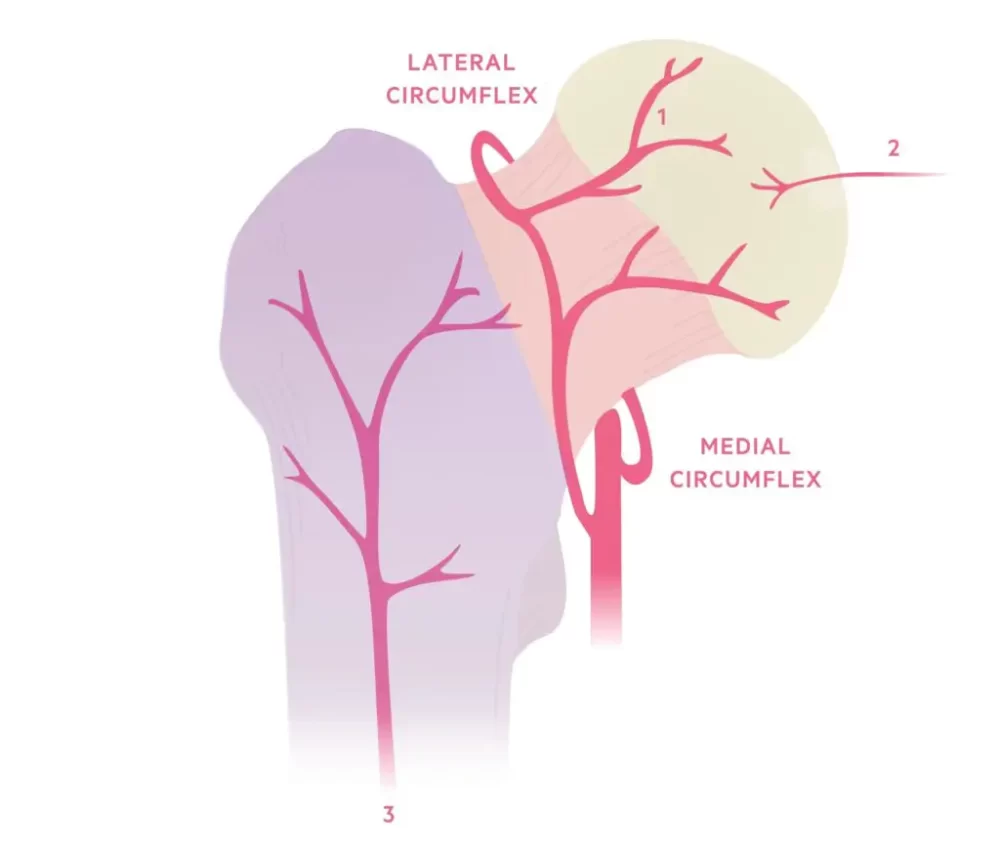

Blood Supply

The femoral head is supplied with blood from three sources:

- Primary blood flow is through the retinal vessels. stems from an extra-capsular artery ring that is reinforced by the superior and inferior gluteal arteries of the internal iliac arteries and supplied by the medial and lateral circumflex vessels (Profundas femoris A.).

- It is not a major source, the foveal artery. nourishes the epiphysis with a small amount of blood as the skeleton is growing. thought to entirely vanish in maturity (ligamentum teres).

- Metaphyseal vessels are not a primary source. Once the skeleton reaches adulthood, the femoral head receives blood supply from metaphysical arteries.

Pathology of Femoral Neck Fracture

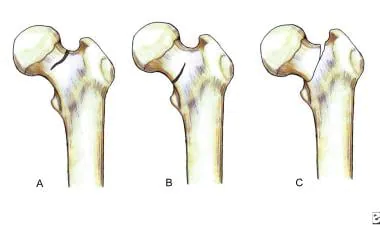

Classification

- Intracapsular fractures: can be either sub-capital (at the neck-head junction) or base-cervical (by the femoral neck’s base).

- Extracapsular: either sub-trochanteric (less than 5 cm distal to the lesser trochanter) or intertrochanteric (between the two trochanters)

The fracture line in relation to the joint capsule can be used to categorize neck of femur fractures:

Proximal femoral fractures are a subtype of femoral neck fractures. A femur’s femoral neck is its weakest point.

The diagnosis and categorization of these fractures is crucial because, depending on the kind of fracture, disruption of the blood supply to the femoral head can result in considerable morbidity. Three categories exist:

- Femoral head/neck juncture is the sub-capital.

- Trans-cervical: the middle section of the femur neck

- Base-cervical: the femoral neck’s base

Most notably, basic cervical fractures are regarded as extracapsular, whereas sub-capital and trans-cervical fractures are classified as intracapsular.

Causes of Femoral Neck Fracture

Those 65 years of age and older are most likely to suffer hip fractures, which are typically the result of falls. Your bones naturally weaken and degrade with age, even from small falls. Hip fractures in children and young adults are primarily caused by sports-related injuries, automobile collisions, and bicycle accidents.

Additional things that can break your hip include:

- Being born with a female-assigned gender.

- For strong bones, you are not getting enough calcium and vitamin D.

- Staying inactive. Strong bones are maintained by weight-bearing activities like walking.

- Smoking’s past.

- Conditions like arthritis can make it difficult to move safely and steadily, as can conditions that cause dizziness or trouble with balance.

- Taking particular drugs, such as long-term COPD or asthma steroid medicines.

Mechanism of Femoral Neck Fracture

Serious trauma in younger patients, such as crashes in motor vehicles.

The mechanism of damage in older patients varies, ranging from falls that land squarely on the hip to twisting injuries when the patient’s torso rotates while their foot is grounded. The shattered bone often has inadequate elastic resistance.

In young patients, the mechanism is primarily axial loading during high-force trauma. An adducted hip during injury results in a hip fracture-dislocation, while an abducted hip during damage causes a fracture in the neck of the femur.

Risk Factors of Femoral Neck Fracture

- Age and Gender: As people age, their muscle mass and bone density tend to decline. Older persons may have vision and balance problems in addition to a higher risk of falling. Hip fractures in women occur around three times more commonly than in males. Women lose bone density faster than males do because menopause lowers estrogen levels, which speeds up bone loss. But dangerously low bone density can also occur in men.

- Medical Conditions: The following illnesses could put you at risk for hip fractures: osteoporosis. This syndrome weakens bones, making them more likely to break.

thyroid issues. Fragile bones may be the result of an overactive thyroid.

Intestinal disorders. Weakened bones can also result from conditions that limit the absorption of calcium and vitamin D.

imbalance issues. Fall risk can be increased by peripheral neuropathy, Parkinson’s disease, and stroke. Too low blood sugar and related low blood pressure. - Certain Medications: Prednisone and other cortisone-containing drugs can erode bone structure over time. Certain drugs, either by themselves or in combination, can cause dizziness, which increases the risk of falling. Drugs classified as sedatives, antipsychotics, and sleep aids are the ones most commonly associated with falls.

- Nutritional Problems: Lack of calcium and vitamin D in the diet lowers a young person’s peak bone mass and increases their risk of fracture later in life. Getting enough calcium and vitamin D is also essential if you want to try to keep your bone density as you age. Underweight people also experience an accelerated loss of bone mass.

- Lifestyle Choices: The risk of fractures and falls is increased by weakening bones and muscles from not getting regular weight-bearing activity, such as walking. Tobacco and alcohol use can interfere with the natural mechanisms that create and preserve bone, which can result in bone loss.

Symptoms of Femoral Neck Fracture

Symptoms of hip fractures typically manifest abruptly. Still, they may start out mildly and get worse with time. Symptoms of a hip fracture include:

- Hip pain: It is typically intense and stabbing. It may also be light or achy, though. Most people report having pain in their thighs, outer hip, pelvic, and groin. Your legs may experience discomfort radiating from your buttocks due to sciatica. Additionally, you can get knee pain.

- Restricted mobility: Most people who suffer hip fractures are unable to stand or walk. Walking might be possible occasionally, but it hurts so much to put weight on one leg.

- Physical changes: Your hip can be bruised. You may notice that one of your legs is shorter than the other. The hip may appear twisted, out of alignment, or rotated.

Diagnosis of Femoral Neck Fracture

Physical Assessment

A doctor examines your hip and pelvis to assess the level of pain, bruising, and swelling. He or she asks where and to what extent you are hurting. When a bone protrudes through the skin, it is called an open fracture. Your doctor will identify this type of fracture fast, often requiring immediate surgery.

Radiography

Radiography images from X-rays Use electromagnetic radiation to find a hip or pelvic shattered bone. They can let your doctor determine whether a bone has been moved after a break or whether a bone has multiple fractures.

- Shenton’s line disruption is the loss of contour between the inferior border of the superior pubic ramus and the medial edge of the femoral neck, which is normally a continuous line.

- The femur’s external rotation makes the lesser trochanter more noticeable.

- The femur is frequently positioned in flexion and external rotation because of the unopposed iliopsoas.

- Asymmetry of lateral femoral neck/head

- Sclerosis in the fracture plane

- Angulated trabeculae of bone

- On an x-ray, nondisplaced fractures could appear minor.

- Because pelvic fractures can resemble the clinical symptoms of hip fractures, it is important to examine the AP pelvis and the lateral hip.

- Trace Shenton’s line

- Check for symmetry, paying special attention to the lesser trochanter, which could mean external rotation.

- Bone trabeculae

- sclerosis

CT Scans

Your doctor may recommend a CT scan to look into a probable fracture pattern or assess the extent of hip joint injury. With a CT scan, doctors can see a fracture from multiple angles because it creates two- and three-dimensional images of the hip and pelvic bones using X-rays and a computer. This examination may also reveal small bone fragments that require surgical removal if they become trapped in the hip joint.

CT scans are used by medical professionals to ensure the proper fit of reassembled bones.

MRI Scans

If your symptoms suggest more damage to your blood vessels, ligaments, tendons, or nerves, or if your doctor thinks you have a stress fracture in your hip or pelvis that is not apparent on an X-ray, they may recommend an MRI. In this test, radio waves and a magnetic field are used to create digitized, three-dimensional images of the soft tissues around the joint.

An MRI could reveal a bone fragment pressing against a nerve or strained or damaged ligaments or tendons. Doctors may also conduct an MRI if your symptoms suggest a fracture but an X-ray reveals no signs of trauma.

If your symptoms suggest more damage to your blood vessels, ligaments, tendons, or nerves, or if your doctor thinks you have a stress fracture in your hip or pelvis that is not apparent on an X-ray, they may recommend an MRI. In this test, radio waves and a magnetic field are used to create digitized, three-dimensional images of the soft tissues around the joint.

An MRI could reveal a bone fragment pressing against a nerve or strained or damaged ligaments or tendons. Doctors may also conduct an MRI if your symptoms suggest a fracture but an X-ray reveals no signs of trauma.

Bone Scans

If you have pain and swelling consistent with a fracture but are unable to get an MRI because of an implanted pacemaker or other medical equipment, your doctor may recommend a bone scan.

To perform this test, a technician will inject a small amount of dye into a vein in your arm. This dye, which is sometimes referred to as a tracer, travels through the bloodstream and collects in the locations where your body is healing tissues and cells.

After the tracer has been in your bloodstream for one or two hours, a radiologist uses a specialized camera to capture photos of your body while scanning it. If it accumulates more in some hip or pelvic regions than others, you may have a fracture.

Treatment of Femoral Neck Fracture

Conservative measures aim to lessen hip pain’s symptoms. The functional outcome is frequently not appreciably different from surgical treatment.

For most other cases, the fractured hip will need to be treated surgically. In order to speed up healing and rehabilitation, doctors would typically recommend surgery for an elderly patient who is functionally healthy. Usually, hip fractures are treated with surgery, medicine, and post-operative therapy.

Medical Treatment

Within two years after suffering a hip fracture, up to 10% of persons 65 years of age or older will suffer another hip fracture. Osteoporosis drugs such as bisphosphonates may lessen the chance of a recurrent hip fracture. Your doctor could advise intravenous (IV) tube delivery of bisphosphonates in order to prevent adverse effects that could make them difficult to tolerate when taken orally.

In general, patients with renal issues should not use bisphosphonates. Rarely, long-term bisphosphonate therapy may result in abnormal hip fractures, eyesight issues, or jaw pain and swelling.

Non-Surgical Treatment

Sometimes surgery is not necessary for your fractured hip. If you had a fracture some time ago and just saw your doctor after the bone started to heal, you won’t require surgery. Still, ignoring a hip fracture is not a smart decision. It might cause a severe handicap that lasts a lifetime.

Furthermore, some patients may choose not to undergo surgery. That’s what conservative therapy are for. These include specific procedures and equipment that help to lessen discomfort and prevent further injury.

Assistive Devices

After breaking your hip, take it easy for at least six weeks. You have to refrain from strenuous exercises and bearing weight on the injured hip until it recovers.

It’s not necessary to stay in bed all day because of that. Getting up and moving around might help avoid deep vein thrombosis and blood clots that result from paralysis. You can get around temporarily with the aid of assistive technology like a walker, crutches, or cane. With these devices, moving about is easier and less stressful on your hips.

Electronic And Ultrasonic Bone Stimulation

Treatment for recently fractured, nonunion, or improperly fusing bones involves bone stimulation. A device can apply low-electric current, low-intensity ultrasound, or extracorporeal shock waves to your bone. It is said to hasten the recovery from hip fractures.

A review of the experiment showed no significant improvements in bone repair, even though there was a chance for decreased pain and improved function. To verify the effectiveness of this treatment, more investigation is required.

The adverse effects of bone stimulators are unknown. However, because further clinical trials are required to prove bone stimulation’s safety and effectiveness in these populations, doctors advise against treating minors or pregnant women with the therapy.

Physical Therapy (PT)

Your physician may suggest that you consult a physical therapist both before and after surgery. By providing your broken bone with nutrients and oxygenated blood, exercise speeds up the healing process.

Sometimes weight-bearing exercises mixed with bed rest are approved by your PT and doctor. Your physical therapist can teach you the fundamentals of stretching and range-of-motion exercises.

There are three ways that PT can benefit you. It prevents the initial weakening of your muscles. It also increases your flexibility. Lastly, it increases your range of motion. Your physical therapy sessions’ duration and frequency will depend on your condition. Visiting a physical therapist can help your hip fracture heal and keep your muscles strong.

Traction

Using pulleys and weights, your surgeon can stretch the muscles around your shattered hip. They are fitted and secured to your leg while you are in the hospital. As the fracture heals, the traction holds your muscles in place. There are situations where this type of non-surgical hip fracture treatment is employed, such as intertrochanteric fractures (see below).

Surgical Treatment

Your hip bone contains a socket that houses your thigh bone or femur, which together make up your hip joint. There are three possible fracture locations, the most common being the femur. There are several surgical methods for handling different types of fractures.

An intracapsular fracture occurs near the ball or neck of the femur. A femur neck fracture is another term for this condition. Surgical options consist of:

- Internal fixation: If you have a displaced femoral neck fracture, your surgeon will use pins, screws, and a metal plate that runs down your femur to hold the broken femur together while it heals.

- Hemiarthroplasty: This procedure involves replacing a hip or joint in part. If the damage is restricted to the end of the bone, your surgeon can decide to remove the ball from your fractured femur and replace it with a metal one. Surgeons usually recommend a partial hip replacement for individuals who do not live independently or who have additional medical concerns.

- Hip replacement: An arthroplasty, or total hip replacement, incorporates the hip socket as opposed to a hemiarthroplasty. Your surgeon reconstructs your hip by welding a prosthetic socket into the bone. The injured femoral ball is then replaced with a ceramic or metal ball that fits the prosthetic socket.

The best course of action for treating hip fractures in otherwise healthy, independent adults is total hip replacement.

Rehabilitation

On the first day following surgery, your care team will likely get you out of bed and moving around. Initially, the focus of physical therapy will be on strengthening and range-of-motion activities. It might be necessary for you to transition from the hospital to an extended care facility, depending on the kind of surgery you underwent and whether you have help at home.

You might work with an occupational therapist in extended care or at home to acquire skills for independence in everyday tasks like dressing, cooking, taking a shower, and using the toilet. Your OT will assess whether using a wheelchair or walker can assist you in regaining your mobility and independence.

Physiotherapy Treatment

Two to three days following surgery:

- Teach the patient to cough and breathe deeply. The goal is to prevent atelectasis and surgical pneumonia.

- With the affected extremity, begin ankle pumps and isometric exercises. The patient is to be ready for an active workout regimen.

- After the patient has been cleared by the doctor to begin this activity, start sitting beside the bed. The goal is to get the patient ready to start the progressive gait training and transfer programs.

Three to five days following surgery

- While taking weight-bearing precautions, teach the patient how to walk. Make the switch to crutches or a walker. The goal is to use an assistance device, to establish an autonomous gait while utilizing the best gait pattern for all surfaces and stairs.

- Start preparing for everyday tasks like getting in and out of bed and using the restroom. The goal is to become independent in every transfer.

- Start a program of active strengthening and range of motion. Workout regimens should be customized for each patient’s needs, however they should usually consist of the following. The goals are to strengthen the affected extremity and promote independence by engaging in physical activity. In the supine position, perform the following exercises: straight leg raise, hip and knee flexion, short arc quadriceps, internal and external rotation, and gluteal and quadriceps sets. Sitting: Ankle pumping, hip flexion, and long-arc quadriceps

- Following internal fixation, full weight-bearing is permitted after three months, with partial weight-bearing advised for eight to ten weeks (depending on radiological assessment of fracture healing).

- As directed by the surgeon, the patient can start engaging in strengthening exercises.

- Additionally, patients should receive proprioceptive and balance rehabilitation because inactivity quickly deteriorates these abilities. Fall prevention and balance education should be considered.

Exercises involving weight bearing are crucial for daily activities, mobility, balance, and overall quality of life. Stepping on and off a block, standing and sitting, tapping the foot, and stepping in various directions are a few examples.

Following a prosthesis replacement, patients need to stay away from the following for about a month.

- >70-90° hip flexion

- Leg rotation from the outside to in

- Leg adduction away from the midline

- Should not incline forward more than ninety degrees from the waist.

Treatment After Surgery

After-operation evaluation

Two to three days following surgery

- Assess the other extremities’ gross muscle strength and range of motion.

- Using isometric muscle contractions, determine the affected extremity’s gross muscular strength.

- Assess the fear of extremity feeling.

- Assess the painful hip’s range of motion within the limits of discomfort.

Three to five days following surgery

- Examine your gait with an assistive device.

- Evaluate functional capacities in relation to bed mobility and transfers.

- Maintain your evaluation of the affected extremity’s gross strength.

Evaluation of outpatients

- Test specific muscle groups differently.

- tests of the ankle, knee, and hip range of motion.

- Examine the walking pattern.

- Analyze your functional capacity.

- Finish specific tests, like the Get-Up and Go Test and the Functional Ambulation Profile.

Security precautions during an assessment

- The weight-bearing status must be determined by the doctor.

- Prior to starting the evaluation, ascertain the heart status.

Complication

Serious problems can result from a hip fracture. Blood clots can occur in veins, usually in the legs. It’s possible for a clot to break apart and lodge in a lung blood artery. This obstruction is called a pulmonary embolism, and it can be fatal.

Other problems could include:

- Pneumonia

- Atrophy of the muscles (wasting of muscle tissue)

- Postoperative infection

- Your bone may not be united properly or at all.

- Mental decline in elderly individuals following surgery

- Bed sores

Prevention

- Eating nutritiously: Diets high in calcium and vitamin D contribute to stronger bones.

- Getting frequent checkups: Ask your physician about bone density testing to detect the early signs of osteoporosis. Your doctor may recommend bisphosphonates, which are medications that both strengthen and reduce the loss of bone.

- Avoiding accidents: Take away any throw rugs or other potential fall hazards from your home. Use caution when using the stairs or walking on frozen surfaces. If you have Parkinson’s disease, speak with your healthcare practitioner about taking care of your body and avoiding falls.

- Maintaining your health: Cut back on drinking, maintain a healthy weight, and give up smoking.

FAQs

What happens if you don’t treat a femoral neck fracture?

Avascular necrosis, or the stoppage of blood flow to the femoral head, can happen if a femoral neck fracture is not treated. This may potentially necessitate a total hip replacement and result in severe, long-lasting impairment.

What is the mechanism of femur neck fracture?

The two most frequent modes of damage are forceful lateral rotation of the lower extremity or a fall that directly strikes the greater trochanter.

Why is the neck of femur fracture life-threatening?

The medial circumflex femoral artery, which is located immediately on the intra-capsular femoral neck, is the main conduit for this. Displaced intra-capsular fractures impede the femoral head’s blood flow, which causes the head to have avascular necrosis.

Can you walk when having a femur neck fracture?

Most of the time, standing or walking will be impossible. Walking is occasionally possible, if painful when the bone is cracked rather than completely broken.

How do you treat a neck fracture of the femur?

Hip reconstruction methods are usually used to treat displaced intracapsular femoral neck fractures in the elderly. A reconstruction prosthesis replaces the femoral head and neck. Hip hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty (THA) operations are commonly included in these procedures.

How long does it take for a femur neck to heal?

You could eventually require physical therapy to help your muscles regain their strength and flexibility. Your chances of making a full recovery might be increased by performing your workouts as directed. The majority of femur fractures heal fully in 4 to 6 months, but you should be able to resume most activities before then.

REFERENCES

- Santos-Longhurst, A. (2018, December 11). Overview of Femoral Neck Fracture of the Hip. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/femoral-neck-fracture

- Femoral Neck Fractures Biomechanics. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Femoral_Neck_Fractures_Biomechanics

- MacManus, D., & Gaillard, F. (2008, May 2). Femoral neck fracture. Radiopaedia.org. https://doi.org/10.53347/rid-1926

- Kazley, J. (2023, May 8). Femoral Neck Fractures. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537347/

- Blomberg, J. (n.d.). Femoral Neck Fractures – Trauma – Orthobullets. https://www.orthobullets.com/trauma/1037/femoral-neck-fractures