Definition of Amputation:

Amputation is the surgical removal of a limb or part of a limb, often performed to treat severe injury, infection, disease (such as diabetes or peripheral artery disease), or certain cancers. It can also be a result of traumatic events.

Rehabilitation, including physical therapy and the use of prosthetics, plays a crucial role in helping individuals regain mobility and adapt to daily life post-amputation.

What is a Amputation?

The surgical removal of all or part of an arm, leg, foot, hand, toe, or finger is known as amputation. Trauma, extended constriction, or surgery are the methods used. As a surgical measure, it is used to reduce pain or a disease process in the affected limb, such as cancer or gangrene. It is sometimes performed on patients as a prophylactic procedure for these issues.

Congenital amputation, a congenital condition in which constrictive bands have severed embryonic limbs, is a unique instance. People who have committed crimes in some countries have been punished by having their hands, feet, or other bodily parts amputated. The most common type of amputation surgery is a leg amputation, which can occur above or below the knee.

Prevalence of Amputations

Every year, one million limb amputations are reported worldwide. Additionally, 57.7 million people worldwide were living with traumatic amputation as of 2017. According to the Amputee Coalition, there are about 185,000 amputations in the US annually. Additionally, more than 2 million Americans had amputations as of April 2021, and another 28 million were at risk of having their limbs amputated surgically because of underlying reasons.

According to data from Stanford Healthcare, the overall number of amputations during the COVID-19 pandemic increased by 49% between March 2020 and February 2021.

Congenital Amputation: What is It?

This term refers to a nonexistent or incompletely formed hand, foot, arm, or leg that is present from birth rather than the result of surgery. Children with congenital amputations may have surgery or artificial limbs in the future if the child, parents, and care team believe it will improve their function and quality of life.

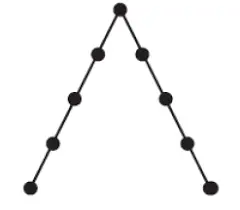

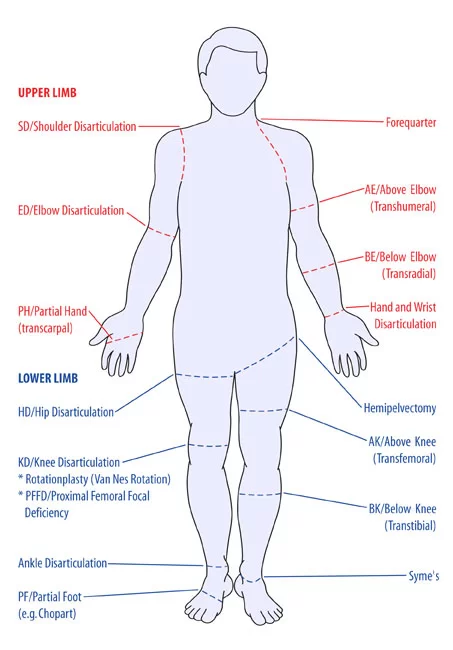

Level of Amputation:

Amputation in the Upper Limb:

- Forequarter

- Shoulder Disarticulation (SD)

- Transhumberal (Above Elbow AE)

- Elbows Disarticulation ED

- Transradial (Below Elbow BE)

- Hand/ Wrist Disarticulation

- Transcarpal (Partial Hand PH)

Amputation Lower Limb:

- Hemicorporectomy

- Hemipelvectomy/ Hindquarter amputation

- Hip Disarticulation

- Short transfemoral(above knee)

- Transfemoral (above Knee)

- Long transfemoral (above knee)

- Knee Disarticulation

- Short transtibial (below knee)

- Transtibial (below knee)

- Long transtibial (below knee)

- Ankle Disarticulation (Symes)

- Tansmetatarsal

- Partial Foot/ray resection

- Toe disarticulation

- Partial Toe

Surgery for Amputation:

The first stage in each surgery is anesthesia. The type of amputation, as previously mentioned in the section on stages of amputation, determines the anesthesia to be used during the procedure.

Particular caution must be used when performing amputation to ensure that the operation does not impair the residual limb’s ability to function. To ensure a healthy stump that can support the weight of a prosthetic limb in the future and lower the risk of complications, it is imperative to condition, shorten, and smooth the residual bone.

In order to preserve the maximum strength of the remaining limb, the muscle is sutured to the bone at the distal residual bone. Myodesis is the term for this process.

It is usually advised to distal stabilize the muscles in order to facilitate efficient muscle contraction and less atrophy. This preserves the soft tissue covering of the remaining bone and permits a more practical use of the stump.

After the amputation surgery is finished, the wound is closed with myoplasty, which involves suturing the opposing muscles of the remaining limb to one another, the periosteum, or the distal end of the severed bone for weight bearing, and then covering it with a bandage. To remove any extra fluid, a drainage tube could be inserted. Therefore, every effort is made to lower the danger of infection.

Procedure of Amputation?

To stop bleeding, the supplying artery and vein must be tied off as the initial step. After transsecting the muscles, an oscillating saw is used to cut through the bone. After filing down the bone’s sharp and uneven edges, skin and muscle flaps are placed over the stump, sometimes with prosthesis attachment components inserted.

Muscle distal stabilization is advised. This enables efficient muscle contraction, which lessens atrophy, permits the stump to be used functionally, and preserves the soft tissue covering of the remaining bone. Myodesis, in which the muscle is connected to the bone or its periostium, is the recommended stabilizing method. Tenodesis may be utilized in joint disarticulation amputations in cases when the muscle tendon is connected to the bone. The tension at which muscles are linked should be comparable to that of normal physiological conditions.

Ideal stump

- Skin flaps: the skin should be pliable, have no scars, and be able to move.

- To lessen the risk of neuroma complications, muscles are separated 3 to 5 cm distal to the level of bone resection, and nerves are carefully pulled and sliced such that they retract well proximally to the bone level.

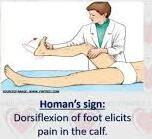

Location of pulses

- Femoral Triangle

- Foot pulse

- Popliteal (behind the knee)

- Femoral (within the femoral triangle)

- The remaining limb is checked for a pulse if a leg has been amputated due to gangrene.

The surgeon may decide to do a closed amputation, which involves sewing skin flaps to seal the wound immediately. Alternatively, if more tissue needs to be removed, the surgeon might keep the incision open for a few days.

After applying a sterile dressing to the incision, the surgical team may cover the stump with a stocking to accommodate bandages or drainage tubes. The physician may apply a splint or put the limb in traction, which uses a device to hold it in place.

Causes of Amputation?

Amputation may be required for a variety of reasons. The most prevalent is peripheral arterial disease, which is impaired circulation caused by artery damage or constriction. The body’s cells cannot receive the oxygen and nutrients they require from the bloodstream if there is insufficient blood flow. As a result, infection may develop and the affected tissue starts to die.

Circulatory disorders

- The most common cause of infection-related amputations is diabetic foot infection or gangrene.

- Peripheral necrosis in sepsis

Neoplasm

- Amputation of the transfemur because of liposarcoma

- Osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, and synovial sarcoma are examples of cancerous bone or soft tissue tumors.

- Melanoma

Trauma

- During World War I, a soldier’s right hand suffered severe amputation of three fingers.

- severe limb injuries, where attempts to rescue the limb are unsuccessful or the limb cannot be saved.

- An unexpected amputation that takes place at the scene of an event and results in the partial or complete amputation of a limb as a direct consequence of the accident is known as traumatic amputation.

- An example of this would be a finger that is severed from the table saw blade.

- Amniotic band amputation during pregnancy.

Deformities

- digit and/or limb abnormalities (such as fibrular hemielia and proximal femoral focused deficit)

- Additional limbs and/or fingers (polydactyly, for example)

Infection

- Bone infection (osteomyelitis)

- Diabetes

- Frostbite

Athletic performance

- Professional athletes occasionally decide to have a non-essential digit removed in order to alleviate persistent pain and performance impairment. Daniel Chick, an Australian Rules football player, decided to have his left ring finger removed since his performance was being hindered by persistent pain and injury. Jone Tawake, a rugby union player, too had a finger amputated. Ronnie Lott, a safety in the National Football League, had the tip of his little finger amputated after it was injured during the 1985 NFL season.

Legal punishment

- Many nations, including Saudi Arabia, Yemen, the United Arab Emirates, Iran, Sudan, and the Islamic parts of Nigeria, use amputation as a legal punishment.

Other causes:

- severe tissue damage due to an infection

- Gangrene

- Trauma from an accident or injury, like a blast wound or crush wound

- Amputation of a congenital or pediatric limb deficit through conversion

- Congenital abnormalities of the limbs or fingers

- Congenital additional limbs or fingers

- Necrotizing or Necrosis Fasciitis

- Cellulitis

- Disease of the Peripheral Arteries

- Frostbite

- malignant or cancerous tumor in the limb’s muscle or bone, for example. Osteosarcoma

- For instance, conditions that impact blood flow Diabetes

Special Investigation:

- X-rays

- CT scan

- Angiogram (outlines blood vessels)

- Doppler ultrasound (occlusion of vessels)

- Venogram and arteriogram

- Radioactive dye injected into the blood

The Amputation Surgery Team

Orthopaedic and orthopaedic oncologic surgeons work with a plastic and reconstructive surgeon, multiple nurses, and surgical technicians to accomplish surgical amputation. After working together to remove the diseased or damaged body part, they create the stump using the remaining bone and soft tissue.

In order to better fit a prosthetic, the surgical team may choose to sculpt the soft tissue at the end of the limb or leave the bone in place for subsequent osseointegration (OI).

Treatment of Amputation?

Pre-Operative Management:

The doctor will recommend medicine and/or counseling if the patient is experiencing grief over the lost limb or phantom pain, which is a feeling of pain in the amputated limb.

Physical therapy frequently starts shortly after surgery and starts with mild stretching and strengthening exercises. It is possible to start using the mechanical limb as soon as 10 to 14 days following surgery.

After Amputation, Healing and Wound Management:

Whether or not you wish to wear a prosthetic, the individualized rehabilitation program and the healing process can give you the best chance to carry on with your everyday activities.

In order to remove the sutures, the post-amputation stump must be kept clean, dry, and wrapped. You will examine the surgical site with your surgeon to check for any areas that are open or not healing well.

After the initial bandaging is taken off, the doctor could recommend a shrinker sock to prevent the stump from getting bigger while the blood vessels heal. This process helps prepare the stump for a prosthesis if you plan to use one. To ensure that it doesn’t pinch the skin, you often start wearing it for a brief period of time before gradually increasing to 23 hours a day.

Phantom Limb and Other Post-Amputation Sensory Issues:

Patients who have had an amputation nearly invariably experience pain and phantom limb symptoms. Although the precise cause is yet unknown, it is likely that remnant nerve connections in the brain and spinal cord “remember” the amputated body part following amputation. It is unknown exactly what causes this illness. These symptoms and indicators can be rather distressing.

During the amputation operation, the surgeon can target the nerves that provide impulses to the brain that impact pain and phantom sensations. These steps can decrease the probability and intensity of problems, even though they might not fully resolve them. Nerve therapies may also be performed later on in patients who have previously undergone amputation but are still experiencing excruciating pain.

Risk of Falling Following Amputation:

Patients who have had a foot or leg amputated are more vulnerable to falls in the initial phases of their recuperation. This is more likely to occur if they forget they have been amputated and try to get out of bed in the middle of the night. Because they can exacerbate the surgical site and necessitate more care or possibly surgery, these falls have the potential to be quite deadly. It could be a useful reminder to never try standing and walking alone to have a wheelchair or walker beside the bed.

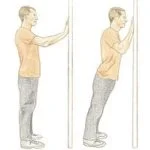

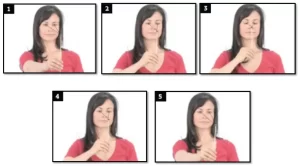

With the help of rehabilitation therapy and exercises performed in front of a mirror, the patient can learn to cope with the loss of the limb and avoid falls.

The management of Pain After Amputation:

Since any treatment might result in unbearable pain, the amputation team does everything they can to make the suffering manageable. Plans for pain management should begin prior to surgery, if at all possible. It can be necessary to do a peripheral nerve block in order to treat pain and phantom limb symptoms.

Physical Therapy Treatment of Amputation:

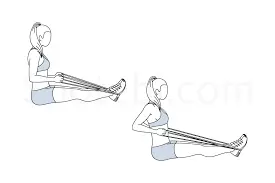

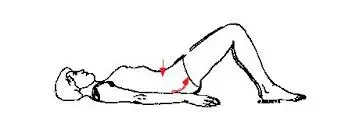

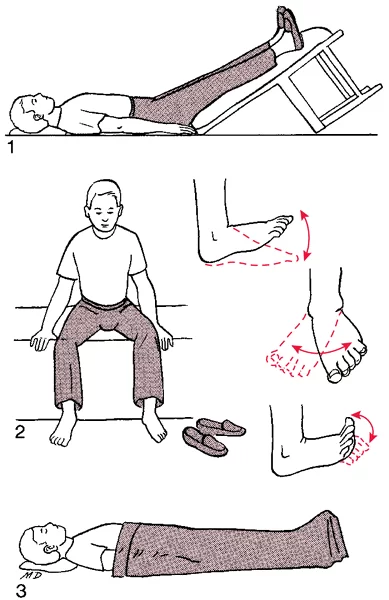

Burger’s Exercise

- increases the patient’s leg’s collateral blood flow

- It lasts for twenty minutes.

- After raising the leg until the toes turn white, it is lowered and then leveled.

- Do this two or three times to increase collateral circulation.

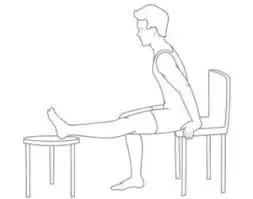

Post-Operative Management:

Post-operative Care:

- To preserve peripheral circulation, keep the remaining leg and stump functioning.

- Maintaining respiratory function is crucial for patients undergoing general anesthesia and smokers.

- Get ready for the rehabilitation of your mobility.

Connective tissue massage

- Effleurage massage

- Rolling

- It relaxes tense muscles and makes them more flexible.

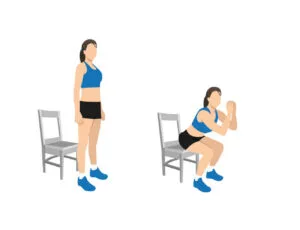

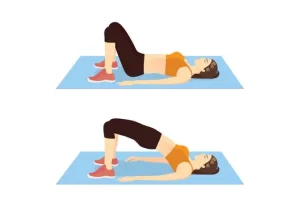

Dynamic stump exercises

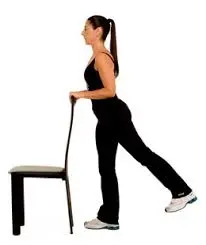

Balance exercise and gait retraining

- Improve the balance between static and dynamic

- Employ crutches, a walking frame, and parallel bars in that order.

- The therapist stands on the amp side and supports the patient with a belt around the waist.

- If the patient is fatigued, take a break.

- Keep the remaining leg and stump functioning to preserve peripheral circulation.

- Preserve respiratory function (particularly for smokers and individuals undergoing general anesthesia).

Stump Care:

- For skin care and hygiene View the amputations handout.

- A flexion of the hip Elevation to lessen edema may promote contracture.

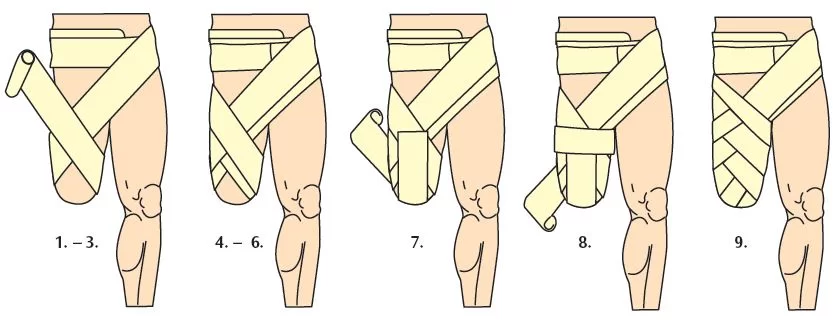

- In order to prevent oedema, which happens when there is no muscular pump and the stump hangs, stump bandaging is used to “cone” the stump.

- In order for the prosthesis to adhere properly and to avoid pressure sores, swelling must be avoided.

- The prosthesis is put on after the stump sock.

- Children who are still growing out of their prostheses require regular cleaning and upkeep.

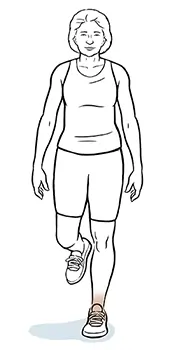

Mobility Aids

The individual’s degree of strength, balance, and fitness determines which mobility aids are best for them:

- Walking frame

- Axillary crutches

- Elbow crutches

- Walking stick

A wheelchair is recommended for amputees who have lost both lower limbs because walking with prosthesis requires a lot of energy.

Psychological Implications of Amputation:

A person’s mental health is greatly impacted by losing a limb, as if they had lost a loved one. Coping with the loss of function and sensation from the amputated leg is challenging. Additionally, it alters how you (the patient) and others perceive your body image, which can result in anxiety and melancholy because negative thoughts are prevalent.

The patient’s psychological health is essential to a successful rehabilitation procedure. Therefore, it is the responsibility of a physical therapist or physiotherapist to understand the natural grieving process and to accept the patient’s worries.

Complications of Amputation:

There aren’t many issues after amputation. Additional issues that are directly linked to the amputated limb are also a possibility.

Your age, the kind of amputation you’ve had, and your general level of fitness and health are just a few of the numerous variables that increase your risk of amputation-related complications.

Compared to emergency amputations, planned surgeries carry a decreased risk of major complications.

The following are some complications that come with having an amputation:

- stump pain (phantom limb” pain)

- slow wound healing

- wound infection

- heart problems such as heart attack

- DVT (deep vein thrombosis)

- pneumonia

In certain instances, additional surgery can be necessary to address developing symptoms or aid in pain relief. For instance, the damaged nerve cluster may need to be removed if neuromas (thickened nerve tissue) are believed to be the source of radiating discomfort.

Prevention:

Techniques for limb-sparing and amputation prevention are based on the issues that could need amputations. Gangrene, which requires amputation as it spreads, is frequently caused by chronic infections, which are frequently caused by diabetes or decubitus ulcers in bedridden people.

First, many patients have poor circulation in their extremities, and second, they have trouble healing infections in limbs with poor circulation. These are the two main problems.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) is also beneficial for crush injuries with poor circulation and significant tissue damage. High levels of revascularization and oxygenation hasten healing and guard against infection.

According to a study, the patented Circulator Boot technique significantly reduced the risk of amputation in individuals with arteriosclerosis and diabetes. According to a different study, it also works well to treat limb ulcers caused by peripheral vascular disease. In order to heal wounds in the walls of veins and arteries and to force blood back to the heart, the boot checks the heart rhythm and compresses the leg in between heartbeats.

Replantations of severed body parts are now feasible for trauma victims thanks to developments in microsurgery throughout the 1970s.

People are shielded from traumatic amputations by the implementation of laws, regulations, and guidelines as well as the use of contemporary equipment.

Prognosis:

Emotional distress and psychological trauma may be experienced by the person. There will continue to be less mechanical stability in the stump. Practical limits resulting from limb loss can be severe or even catastrophic.

Between 50 and 80 percent of amputees report experiencing phantom limbs, which is the sensation of body parts that are no longer there. These limbs may feel stiff, dry or damp, locked in or confined, itchy, aching, burning, or as though they are moving. According to some scientists, the reason for this is that the brain contains a neural map of the body that communicates information about limbs to the rest of the brain, regardless of whether they are present or not. Phantom pain and phantom sensations can also happen after body parts other than the limbs are removed, such as after the breast is amputated, a tooth is extracted (phantom tooth pain), or an eye is removed (phantom eye syndrome).

Unexplained sensation in a body component unrelated to the amputated limb is a comparable condition. A person who has had an arm amputated may experience unexplained pressure or movement on his face or head, according to a theory that the area of the brain that processes stimulation from amputated limbs expands into the surrounding brain after being deprived of input (Phantoms in the Brain: V.S. Ramachandran and Sandra Blakeslee).

Since it allows the user to perceive proprioception of the prosthetic limb, the phantom limb frequently facilitates adaption to a prosthesis. Some kinds of stump socks can be worn in place of or in addition to a prosthesis to promote better resistance, use, comfort, or healing.

Heterotopic ossification is another adverse outcome that may occur, particularly when a brain injury is coupled with a bone injury. Nodules and other growths can interfere with prosthesis and occasionally necessitate additional procedures. The brain instructs the bone to develop rather than scar tissue. During the Iraq War, soldiers injured by improvised explosive devices have been particularly susceptible to this kind of injury.

A lot of amputees lead active lives with little limitations thanks to advancements in prosthetic technology. To provide amputees with the chance to participate in adaptive sports like amputee soccer and athletics, organizations like the Challenged Athletes Foundation were established.

Almost 50% of people who undergo a vascular disease-related amputation will pass away within five years, typically as a result of their numerous co-morbidities rather than the actual effects of the amputation. The five-year mortality rates for prostate, colon, and breast cancer are lower than this. Up to 55% of diabetics who have had their lower extremities amputated may need to have their second leg amputated within two to three years.

Conclusion:

While it presents physical and emotional challenges, improvements in medical technology, prosthetics, and rehabilitation have significantly improved the quality of life for amputees. With the right medical care, psychological support, and rehabilitation, people can adapt and regain their independence.

Amputation is a life-changing procedure that is occasionally required due to severe trauma, infections, tumors, or chronic conditions like diabetes. Further research and innovation in surgical techniques and prosthetic development will further improve outcomes for those undergoing amputation.

FAQs

What is the treatment for amputations?

Your wound will be sutured shut following the amputation. A tube may be inserted beneath your skin to remove any extra fluid, and it will be bandaged. To lower the danger of infection, the bandage must typically be left in place for a few days.

Amputations are performed by whom?

However, even though vascular and general surgeons execute around 90% of the amputations performed in this nation, they hardly ever participate in amputee clinic sessions or act as other team members.

Can I go home with my amputated leg?

Possession of human body parts, even if they are your own, is also prohibited in several places. States differ greatly in these laws, with some being more lenient than others. Hospital regulations: Internal policies at the majority of medical facilities prohibit patients from bringing severed body parts home.

How do you amputate feet?

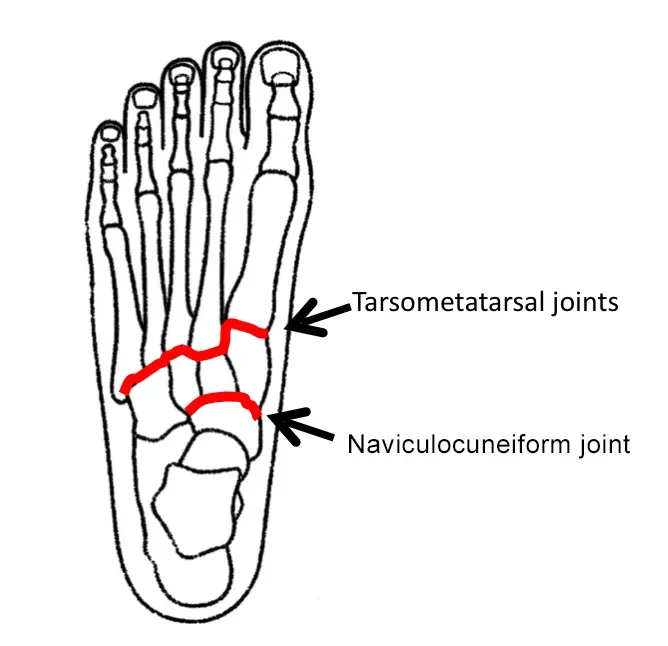

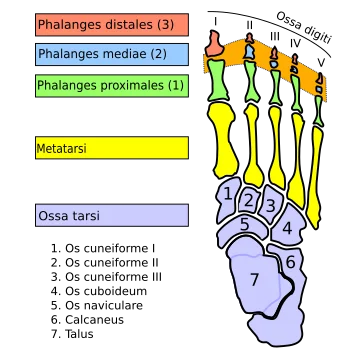

LisFranc’s amputation entails detaching the cuboid and cuneiform bones from the forefoot’s metatarsal bones at the tarsometatarsal joints. The talus and navicular bones, as well as the calcaneus and cuboid bones, are disarticulated at the midtarsal joints in Chopart’s amputation.

Which body part is most frequently amputated?

Above-the-knee and toe amputations were more prevalent than other types of amputations, accounting for 56 instances (25.92%) and 54 cases (25%) of the total. Lower limb amputations were more common, both major and minor. Lower extremity amputations occurred in all patients with diabetes.

Amputate means to chop off, right?

Amputation is the process of cutting something off. An amputation is a procedure in which a physician removes a body part due to a serious injury or infection. It is possible for a finger, foot, or leg to be amputated.

What happens to bodily parts that have been amputated?

The limb is destroyed after being taken to biohazard crematoria. The limb is given to a medical school to be used in anatomy and dissection courses. The limb will be given to the patient in rare circumstances if they want it for personal or religious reasons.

At what age do amputations occur most frequently?

The majority of amputations occur in older persons; over 45% of people who lose limbs are 65 years of age or older, and almost 42% are between the ages of 45 and 64.

How are limbs amputated?

The goal of an amputation is to preserve as much good tissue as possible while removing all damaged tissue. To decide where to make an incision and how much tissue to remove, a doctor may employ a number of techniques. Checking for a pulse around the area the surgeon intends to cut is one of these.

Can someone who has had two legs severed walk?

People who have had their legs amputated may find it easier to move around using prosthetic legs, often known as prostheses. They imitate how a real leg works and occasionally even how it looks. While some people may walk freely with a prosthetic leg, others still use a cane, walker, or crutches.

Which two kinds of amputations are there?

First, doctors usually distinguish between two types of amputations: top and lower. Upper amputations affect the arm, wrist, or fingers. Toes, ankles, or legs are affected by lower amputations.

What is meant by amputate?

The loss or removal of a body part, such as a finger, toe, hand, foot, arm, or leg, is known as amputation. It can be a life-altering event that impacts your mobility, employment, social interactions, and independence.

Why are amputations performed?

While surgical amputations can be caused by a number of illnesses, such as blood vessel disease, cancer, infection, severe tissue damage, malfunction, discomfort, etc., traumatic amputations are the result of accidents or injuries. Missing a body component before birth is known as congenital amputation.

How do amputations take place?

General anesthesia, which puts the patient to sleep, or spinal anesthesia, which numbs the body from the waist down, can be used to execute amputations. During an amputation, the surgeon keeps as much healthy tissue as possible while removing all damaged tissue.

Do amputations pain?

Two things can happen when you lose a limb. The first is the psychological and bodily pain of an amputation. For over 80% of amputees, the resulting chronic pain can be nearly as incapacitating as the initial damage. Some claim that the removed limb is the source of their discomfort.

When a body component is severed, what happens?

The pathology department is frequently given two choices after the inspection: either the removed body part is disposed of as “specific hospital waste” or it is employed for medical research. Following that, this trash is disposed of with other hospital waste.

References

- Dhameliya, N. (2024, July 20). Amputation – causes, types, procedure, exercise. Samarpan Physiotherapy Clinic. https://samarpanphysioclinic.com/amputation/

- Professional, C. C. M. (2024, October 15). Amputation. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/procedures/21599-amputation

- Wikipedia contributors. (2025, February 4). Amputation. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amputation

- Crna, R. N. M. (2022, March 31). Amputation: Causes, Statistics, and Your Most-Asked Questions. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/amputation