Introduction:

Aphasia is an acquired language problem caused by injury to the brain’s language centers, marked by difficulties in verbal or written expression, comprehension, or both. Most cases of aphasia contain a combination of these deficits, impacting several language functions. Broca and Wernicke aphasia, conduction aphasia, transcortical motor or sensory aphasia, and alexia, with or without agraphia, are common clinical forms.

While stroke, especially ischemic stroke, is the most common cause of aphasia, others include traumatic brain injury (TBI), brain tumors, and neurodegenerative diseases. Aphasia symptoms can range from mild impairment to a complete loss of basic language components, such as semantics, grammar, phonology, morphology, and syntax, and they can affect written language, verbal communication, or, more frequently, both. Patients may present with difficulties articulating words, forming sentences, comprehension deficits, or a combination of these.

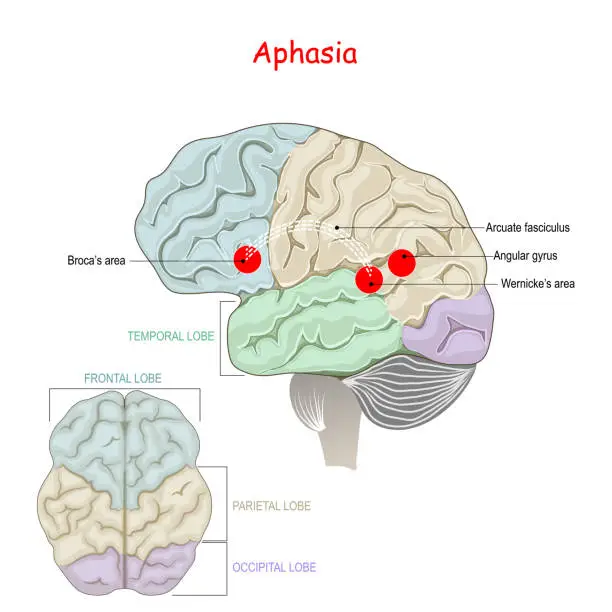

Wernicke and Lichtheim created the standard model of aphasia in the 19th century, and Geschwind improved it neuroanatomically in the 1960s. The basis for comprehending the clinical characteristics of aphasia and the associated neuroanatomical abnormalities is provided by this model. The language centers of the brain are usually found in the peri-Sylvian region of the dominant hemisphere, which is usually the left. The Wernicke region in the posterior superior temporal gyrus processes spoken language after it has been received by the primary auditory cortices in the Heschl gyrus (transverse temporal gyrus). The Wernicke region receives written language after passing through the angular gyrus and the main visual cortex in the occipital brain.

The inferior frontal region’s Broca area is in charge of speech motor execution and sentence construction. The neuronal route that links the Wernicke and Broca areas is called the arcuate fasciculus. The classical aphasia model states that the location of the brain lesion correlates with particular aphasia disorders. Fluent aphasia, which is characterized by severe paraphasia and reduced understanding, is caused by a posterior lesion involving the Wernicke region. Nonfluent aphasia, on the other hand, is caused by an anterior lesion that affects the Broca area. Patients with this condition have adequate comprehension but generate speech that is telegraphic, effortful, and dysprosodic, free of paraphasic errors. Conduction aphasia, which is typified by poor repetition and phonemic paraphasia, is caused by a lesion in the arcuate fasciculus or the white matter tract that connects the Wernicke and Broca regions.

The most prevalent kind of aphasia, known as global aphasia, affects language expression and comprehension to differing degrees. Like Broca aphasia, transcortical motor aphasia is nonfluent but preserves repetition. Similar to Wernicke aphasia but with intact repetition, transcortical sensory aphasia is a fluent aphasia with decreased comprehension. Echolalia and perseverance are examples of excessive repetition that are frequently seen in patients with transcortical motor or sensory aphasia. A minor injury to the dominant peri-Sylvian region causes anomia, a milder type of aphasia.

Hickok and Poeppel created the dual-stream concept, also known as the contemporary language model, which is backed by recent neuroimaging research like as diffusion tensor imaging, MRI tractography, and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Two primary language processing streams including cortical and subcortical areas are described below by this dual-stream concept.

The dorsal stream, which connects the frontal speech areas with the temporoparietal junction, handles auditory-to-articulation information. It is situated in the dominant hemisphere region. For the development of fluent speech, this stream is essential. The gray matter of the frontoparietal areas is the primary target of the dorsal stream, according to lesional studies.

Both temporal lobes contain the ventral stream, which is responsible for processing auditory-to-meaning information a crucial component of auditory understanding. A large portion of the gray matter in the lateral temporal lobe is included in this stream. Rather than involving the white matter tract of the arcuate fasciculus, conduction aphasia is caused by lesions in gray matter, specifically in the area Spt (Sylvian fissure, parietal-temporal junction), a posterior region that is a part of the dorsal stream.

By breaking the links within the cortical-subcortical language networks, subcortical structural lesions can also cause aphasia in addition to cortical language areas. These causes are uncommon, though. Sometimes aphasia is caused by lesions in the cerebellum, thalamus, and basal ganglia. When basal ganglia injuries cause aphasia, it is usually mild and manifests as a loss of linguistic expressiveness, including word fluency, although understanding and repetition are unaffected.

Affected left-sided ventral anterior or paramedian nuclei can result in either fluent or nonfluent thalamic aphasia. With relative preservation of repetition, lexical-semantic impairments are the main outcome of this kind of aphasia. Rarely, aphasia which is usually characterized by deficiencies in word retrieval, semantics, and syntax can result from cerebellar injuries on either side. Generally speaking, subcortical aphasia is milder and linked to a better prognosis.

A person’s language skills must be markedly compromised in one or more of the four communication domains in order to be diagnosed with aphasia. A discernible drop in language skills over a brief period of time is necessary in the case of progressive aphasia. Spoken language production, spoken language understanding, written language creation, and written language comprehension are the four components of communication. Functional communication may be impacted by deficiencies in any of these areas.

For a person to be diagnosed with aphasia, their language abilities must be significantly impaired in one or more of the four communication domains. Progressive aphasia requires a noticeable decline in linguistic abilities over a short time span. The four components of communication are written language creation, written language comprehension, spoken language production, and spoken language understanding. Deficits in any of these areas can affect functional communication.

The brain’s communication systems are malfunctioning due to injury to one or more of them in aphasia. Aphasia is not caused by brain damage that results in motor or sensory deficiencies, which results in improper speech; rather, aphasia is a condition that affects a person’s language cognition rather than speech mechanics. Nonetheless, a person may experience both issues, for example, if a hemorrhage damages a significant portion of the brain. The socially accepted set of standards and the mental processes involved in communication (as it influences both verbal and nonverbal language) are both incorporated into a person’s language skills. Other peripheral motor or sensory difficulties, such as paralysis of the speech muscles or a general hearing impairment, do not cause aphasia.

Although aphasia is by definition caused by acquired brain injury, neurodevelopmental variants of auditory processing disorder (APD) can be distinguished from aphasia. However, acquired epileptic aphasia has been considered a type of APD.

Epidemiology

One in every 272 Americans suffers with aphasia, with 180,000 new instances reported annually in the US, according to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). Cerebrovascular accidents are the cause of about one-third of these instances. The most prevalent kind is called global aphasia.

Men and women get stroke-induced aphasia at the same rate, while the prevalence varies with age. If you are 65 or younger, your chances of getting the illness are 15%, whereas if you are 85 or older, your chances are 43%. Damage to the language-processing areas of the brain causes aphasia in between 25% and 40% of stroke survivors.

Pathophysiology

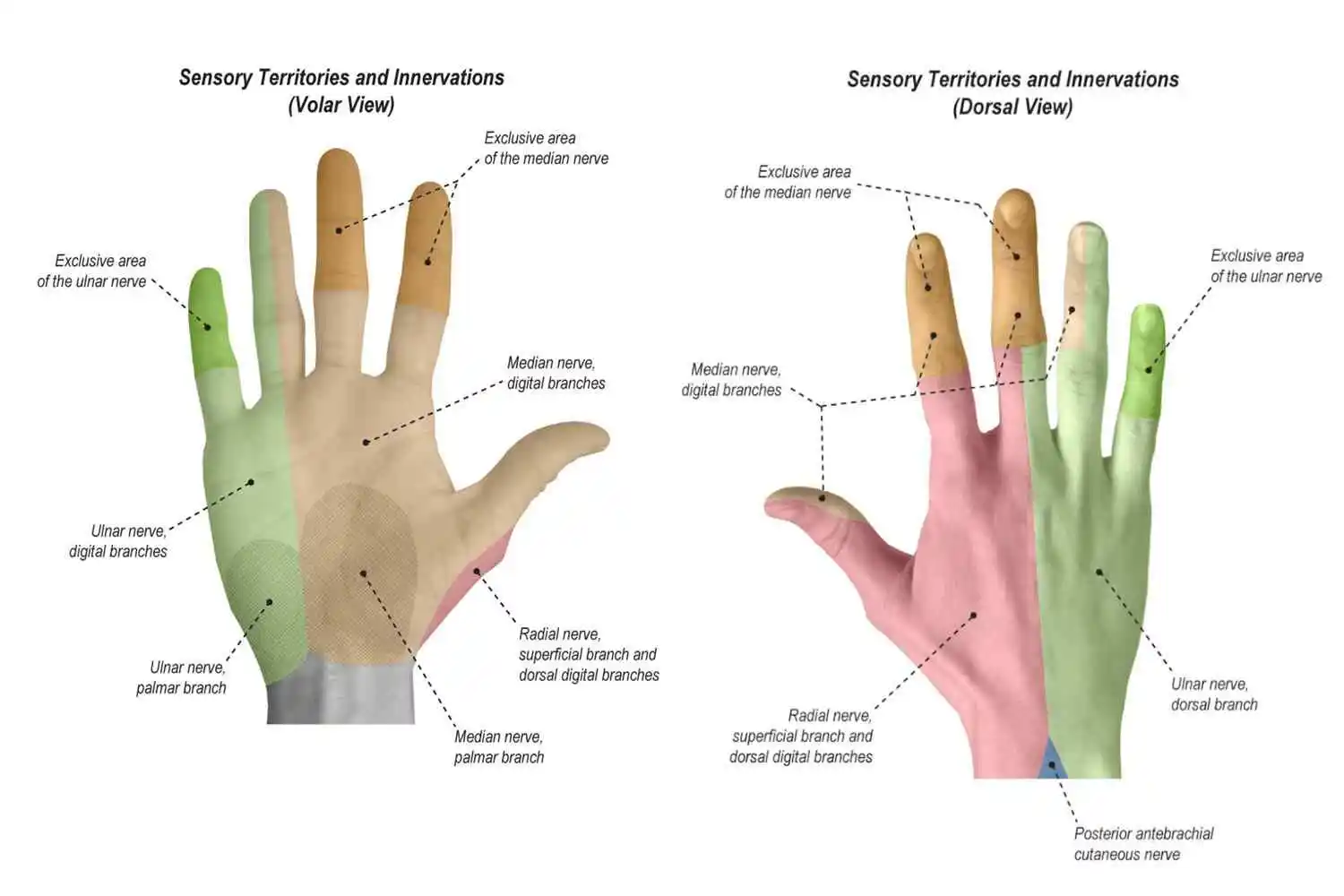

Lesions in the language regions of the brain, which are usually found in the dominant hemisphere (usually the left hemisphere for most people), are the cause of aphasia. The arcuate fasciculus and the Wernicke and Broca areas are important regions. The current dual-stream neuroanatomic model of aphasia states that nonfluent, effortful aphasia is caused by injury to the dorsal stream, mainly in the frontoparietal areas. On the other hand, fluent aphasia with comprehension impairments is caused by injuries that impact the ventral stream in the temporal lobes.

Gray matter involvement in the Spt area, which is a component of the dorsal stream, is most frequently linked to conduction aphasia. Disruptions in the connections between the peri-Sylvian language region and the association areas of the brain cause transcortical aphasia. A lesion in the parietal lobe’s dominant angular gyrus, posterior inferior temporal region, and adjacent supramarginal gyrus causes alexia with agraphia, which is characterized by an inability to read and write. A tiny lesion affecting the dominant occipital lobe and the nearby splenium of the corpus callosum is the cause of alexia without agraphia.

The dominant left MCA is the vascular region most commonly affected by acute ischemic stroke, which is the most prevalent cause of aphasia. Global aphasia usually occurs when the entire dominant MCA area is affected. Nonfluent Broca aphasia, also called dorsal stream aphasia, is usually caused by occlusion of the anterosuperior branch of the MCA and is characterized by a preponderance of difficulties in language production while understanding is unaffected. On the other hand, fluent Wernicke aphasia, also known as ventral stream aphasia, is caused by obstruction of the posteroinferior branch and is linked to significant comprehension impairments. Individuals who suffer from this illness frequently struggle with writing, reading, and repetition.

Watershed infarctions caused by abrupt cerebral hypoxemia, such as severe hypotension or cardiac arrest, frequently result in transcortical aphasia. A watershed infarction between the anterior cerebral artery and MCAs causes transcortical motor aphasia, which can occasionally be accompanied by blockage of the dominant internal carotid artery. A watershed infarction between the dominant middle and posterior cerebral infarcts causes transcortical sensory aphasia. Damage to subcortical regions located deep within the left hemisphere, such as the thalamus, caudate nucleus, and internal and external capsules, can also occasionally cause aphasia.

TBI and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and frontotemporal dementia can also cause aphasia. The main symptom of primary progressive aphasia, a type of frontotemporal dementia, is a progressive loss of language because of degeneration and death of neurons in the language regions of the brain. Brain tumor mass impacts and infections are two more factors that can harm language areas.

Classification of Aphasia:

The best way to conceptualize aphasia is as a group of diseases rather than as a single issue. The specific mix of linguistic strengths and impairments will vary from person to person with aphasia. Therefore, simply documenting the different challenges that can arise in different people, much alone determining the best way to manage them, is a significant challenge.

The majority of aphasia classifications tend to categorize the different symptoms into broad groups. One popular method is to differentiate between nonfluent aphasias, which are characterized by extremely halting and effortful speech that may only contain one or two words at a time, and fluent aphasias, where speech is still fluent but content may be lacking and the person may have trouble understanding others.

But no such wide-ranging classification has shown out to be entirely sufficient. Even within the same broad category, there is a great deal of diversity among individuals, and aphasias can be very selective. For example, individuals with anomic aphasia, a naming impairment, may only be able to name colors, structures, or persons. Sadly, tests that define aphasia in these categories have continued to exist. This gives false descriptions of a unique pattern of challenges and is not helpful to those who have aphasia.

As people age normally, they also experience common speech and language impairments. Language processing might slow down as we become older, which can lead to problems with reading comprehension, vocal comprehension, and word recognition. However, unlike some aphasias, each of these does not impair one’s ability to operate in day-to-day activities.

Boston classification:

Wernicke Aphasia (Receptive)

The Wernicke region (Brodmann area 22) or, more posteriorly, the superior temporal gyrus, which is the hub for language processing and understanding, is usually where the lesion linked to Wernicke aphasia is found. For additional information, please refer to “Neuroanatomy, Wernicke Area,” a companion site to StatPearls. Individuals with fluent aphasia have normal prosody. Their naming and understanding skills, however, are significantly compromised, and they frequently exhibit varied degrees of paraphasia, such as phonemic or literal paraphasia, as well as neologisms or jargon. Because of their cognitive issues, these patients can be difficult to communicate with. Writing and reading skills are also impacted. Neologisms are made-up terms, whereas jargon is a mix of real words and neologisms that don’t make sense in context. Usually, these patients are not conscious of their mistakes or the meaninglessness of their speech.

Receptive aphasia, also known as Wernicke’s aphasia or fluent aphasia, is characterized by the use of extended, meaningless sentences, superfluous words, and even the creation of new “words” (neologisms). For instance, “delicious taco” might be said by someone with receptive aphasia, which translates to “The dog needs to go out so I will take him for a walk.” They have fluent, but incomprehensible, written and spoken language, and poor reading and aural comprehension. People with receptive aphasia typically struggle to understand their own and other people’s speech, and as a result, they frequently don’t realize when they’re making mistakes.

Lesions in the posterior region of the left hemisphere at or close to Wernicke’s area are typically the cause of receptive language impairments. It frequently arises from injury to Wernicke’s area, which is located in the temporal region of the brain. Although there are many different issues that might cause trauma, stroke is the most common cause.

Broca Aphasia (Expressive)

The Broca area, more especially the anterior portion of the peri-Sylvian region of the inferior frontal gyrus, is where the lesion linked to Broca aphasia is found. This area is in charge of the motor components of speech as well as the development and expression of sentences. For additional information, please refer to “Neuroanatomy, Wernicke Area,” a companion site to StatPearls. Patients’ speech is effortful, nonfluent, and dysprosodic; it is frequently telegraphic and lacks conjunctions, prepositions, articles, adjectives, and adverbs. Name recognition and repetition skills are impacted to varied degrees, but comprehension stays normal. Their ability to communicate verbally is reflected in their reading and writing skills. Patients can usually express what they want to say by employing essential content words such nouns, verbs, and certain adjectives, even when their speech is nonfluent and lacks grammatically significant vocabulary.

People who have expressive aphasia, also known as Broca’s aphasia, usually communicate in brief, meaningful sentences that require a lot of work. Therefore, it is classified as a nonfluent aphasia. Those who are affected frequently leave out terms like “is,” “and,” and “the.” For instance, “walk dog” may mean “I will take the dog for a walk,” To varied degrees, people with expressive aphasia can comprehend other people’s speech. As a result, individuals are frequently conscious of their challenges and are prone to get irritated by their speech issues. Evidence indicates that Broca’s aphasia may have its roots in an incapacity to interpret syntactical information, despite the fact that it may seem to be only a language production problem. People who have expressive aphasia may exhibit speech automatism, which is another name for repeated or recurring utterance.

Both modalizations (‘I can’t…, I can’t…’), expletives/swearwords, numbers (‘one two, one two’), and non-lexical utterances composed of repeated, legal, but meaningless, consonant-vowel syllables (e.g., /tan tan/, /bi bi/) are examples of repeated lexical speech automatisms. In extreme situations, the person could only be able to produce the same speech automatism whenever they try to speak.

Conduction Aphasia

The arcuate fasciculus, the neuronal route that connects the Wernicke area to the Broca area, is where the lesion linked to conduction aphasia is situated. More precisely, as previously mentioned, the lesion is located in the gray matter in the area Spt. Phonemic paraphasia and poor repetition are common symptoms of conduction aphasia. For additional information, please refer to “Conduction Aphasia,” a complementary resource on StatPearls.

The connections between the speech-production and speech-comprehension regions are impaired in people with conduction aphasia. The structure that relays information between Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas, the arcuate fasciculus, may be damaged. However, following damage to the auditory cortex or insula, similar symptoms may manifest. Oral expression is fluid with sporadic paraphasic errors, and auditory comprehension is almost normal. Paraphasic errors include phonemic/literal or semantic/verbal. Repetition ability is low. White matter tract injury results in transcortical and conduction aphasias. These aphasias cause a disconnection between the language centers rather than harming the language centers’ brain.

Arcuate fasciculus injury results in conduction aphasia. Wernicke’s and Broca’s regions are connected by a white matter tract called the arcuate fasciculus. Conduction aphasia sufferers usually have modest difficulties with word retrieval and speech output, poor speech repetition, and high language comprehension. Most people with conduction aphasia are conscious of their mistakes. There are two types of conduction aphasia that have been identified: repetition conduction aphasia, which involves repeating short, common syllables that are not connected, and reproduction conduction aphasia, which involves repeating a single, relatively unusual multisyllabic word.

Transcortical Sensory Aphasia

The Wernicke region is spared and isolated in transcortical sensory aphasia, and the lesion is situated surrounding it. Patients can repeat speech effectively despite having poor understanding, which can result in persistence and echolalia. Furthermore, semantic paraphasia is frequently seen in these patients.

Though their capacity for repetition may not be affected, those with transcortical sensory aphasia, which is theoretically the most widespread and possibly one of the most complex types of aphasia, may exhibit similar deficiencies to those with receptive aphasia.

Transcortical Motor Aphasia

The Broca area is spared and isolated in transcortical motor aphasia, while the lesion is situated around it. Despite their inability to speak fluently, patients are able to repeat lengthy, intricate sentences and frequently exhibit persistence and echolalia. They usually don’t say anything, but sometimes they will say one or two words.

Transcortical motor aphasia, transcortical sensory aphasia, and mixed transcortical aphasia are examples of transcortical aphasias. Although they have trouble choosing words and producing speech, people with transcortical motor aphasia usually maintain intact comprehension and an awareness of their mistakes. Individuals who suffer from transcortical sensory and mixed transcortical aphasia struggle with understanding and are not aware of their mistakes. All forms of transcortical aphasia can fully recover, according to modest studies, even though some of them have more severe deficits and poor understanding.

Global Aphasia

Lesions of various sizes and locations cause global aphasia, which mostly affects the parts of the brain fed by the dominant left MCA in the peri-Sylvian region. This type of aphasia is the most prevalent and severe. Patients usually show little to no comprehension of spoken or written language and only create a few familiar words. They also lack the ability to read and write.

Anomia (Nominal Aphasia)

The mild type of aphasia known as anomia, or nominal aphasia, is believed to be caused by lesions that impair the dominant angular gyrus. It is now known, therefore, that this illness can result from even minor or minor lesions in the language areas. Finding words is the main challenge for patients.

Those who suffer from anomic aphasia have trouble naming. Individuals who suffer from this aphasia may have trouble naming certain words, either because of their semantic category (e.g., difficulty naming words related to photography, but nothing else), grammatical type (e.g., problem naming verbs and not nouns), or a more general naming difficulty. People frequently speak in grammatically correct but meaningless ways. There is a tendency to preserve auditory comprehension. Alzheimer’s disease manifests as anomic aphasia, which is the aphasial manifestation of tumors in the language zone. The mildest type of aphasia, anomic aphasia, suggests a higher chance of recovery.

Since global aphasia affects reading, writing, and expressive and receptive language, it is regarded as a significant impairment in many language elements. Despite these numerous deficiencies, there is proof that speech-language therapy helps people. Despite the fact that people with global aphasia will never be proficient communicators, listeners, writers, or readers, objectives can be made to enhance their quality of life. Including personally relevant material in therapy is particularly crucial because people with global aphasia typically respond strongly to it.

Subcortical Aphasia

Lesions in the basal ganglia can cause moderate aphasia, which is characterized by a loss of linguistic expressiveness, including word fluency, but comprehension and repetition are unaffected. When the paramedian or left-sided ventral-anterior nuclei are affected, thalamic aphasia results. With a relative preservation of repetition, this kind of aphasia mainly results in lexical-semantic deficiencies and can be either fluent or nonfluent. Rarely, cerebellar lesions on either side can result in aphasia, which usually presents as problems with syntax, semantics, and word retrieval. In general, subcortical aphasia has a better prognosis and is typically milder.

Cognitive neuropsychological approaches:

The majority of people do not cleanly fit into one category, despite the fact that localizationist techniques offer a helpful means of grouping the many patterns of language difficulty into broad categories. Another issue is that the classifications, especially the more prominent ones like Wernicke’s and Broca’s aphasia, are still quite general and do not really represent an individual’s challenges. As a result, there may be a great deal of variation in the kinds of challenges that people encounter, even among those who fit the requirements for being categorized into a subtype.

Cognitive neuropsychological methods seek to pinpoint the essential linguistic abilities or “modules” that are malfunctioning in each person rather than assigning each person to a particular category. A single module or several modules may present challenges for an individual. A framework or theory outlining the abilities and modules required to complete various linguistic activities is necessary for this kind of approach. The Max Coltheart model, for instance, specifies a module that can identify phonemes as they are uttered, which is crucial for any task involving word identification.

Similar to this, a module is essential for any task requiring the production of lengthy words or speech strings since it maintains the phonemes that the user intends to use in speech. Following the establishment of a theoretical framework, a particular test or series of tests can be used to evaluate how well each module functions. Using this paradigm in a clinical environment typically entails doing a series of tests that evaluate one or more of these modules. Therapy can start to address the skills that have the most impairment once it has been determined which skills or modules are affected.

Classical-localizationist approaches:

The goal of localizationist techniques is to categorize aphasias based on their primary presenting features and the brain regions that most likely caused them. These methods, which draw inspiration from the early research of nineteenth-century neurologists Paul Broca and Carl Wernicke, distinguish between two main kinds of aphasia and numerous smaller subgroups:

“Broca’s aphasia” or “motor aphasia” are other names for expressive aphasia, which is characterized by effortful, stopped, and fragmented speech but well-preserved cognition in comparison to expression. The anterior region of the left hemisphere, particularly Broca’s area, is usually damaged. Because the left frontal lobe is also crucial for movement of the body, especially on the right side, people with Broca’s aphasia frequently have right-sided weakness or paralysis of the arm and leg.

Fluent speech is a hallmark of receptive aphasia, commonly referred to as “sensory aphasia” or “Wernicke’s aphasia,” which is characterized by significant challenges comprehending words and sentences. Despite being fluid, the speech could be deficient in important substantive terms (nouns, verbs, and adjectives) and contain erroneous or even nonsensical words. Wernicke’s region and other lesions to the posterior left temporal cortex have been linked to this subtype. Because their brain lesion is not close to the areas of the brain that regulate movement, these people typically do not have any physical weakness.

With conduction aphasia, a person may have disproportionate difficulty repeating words or sentences, but their speech and comprehension are still fluid. The arcuate fasciculus and the left parietal area are usually affected.

The capacity to repeat words and sentences is disproportionately intact in transcortical motor aphasia and transcortical sensory aphasia, which are comparable to Wernicke’s and Broca’s aphasia, respectively.

These classical aphasia subtypes are also grouped into two larger classes by recent classification schemes that use this approach, such as the Boston-Neoclassical Model: the nonfluent aphasias, which include Wernicke’s aphasia, conduction aphasia, and transcortical sensory aphasia, and the nonfluent aphasias, which include Broca’s aphasia and transcortical motor aphasia. These schemes also identify a number of additional subtypes of aphasia, such as global aphasia, which is defined by a significant impairment in both speech comprehension and expression, and anomic aphasia, which is characterized by a selective problem in finding the names for things.

The presence of other, more “pure” forms of language disorders that might only impact one language competence is also acknowledged by many localizationist methods. For instance, someone with pure alexia might be able to write but not read, and someone with pure word deafness would be able to read and speak but not comprehend what is being said to them.

Progressive aphasias:

The neurodegenerative focal dementia known as primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is linked to progressive diseases or dementias like Alzheimer’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, and frontotemporal dementia/pick complex motor neuron disease, which is the progressive loss of cognitive function. Up to the latter phases, language function gradually declines although memory, visual processing, and personality are mostly intact. Word-finding (naming) issues are typically the first symptoms to appear, followed by comprehension (sentence processing and semantics) and grammar (syntax) impairments. PPA is distinct from other types of dementias in that language loss occurs prior to memory loss.

Individuals with PPA may find it difficult to understand what other people are saying. Additionally, they may struggle to come up with the appropriate words to form a statement. Progressive nonfluent aphasia (PNFA), semantic dementia (SD), and logopenic progressive aphasia (LPA) are the three categories of primary progressive aphasia.

A fluent or receptive aphasia known as progressive jargon aphasia[citation needed] causes a person to speak incoherently even though it seems to make sense to them. Although the speaker’s syntax and grammar are correct and their speech is fluid and effortless, they struggle with noun choice. The chosen word will either be replaced with sounds or with another that sounds, looks, or has some other link to the original.

As a result, jargon aphasics frequently employ neologisms, and they may persist if they attempt to substitute sounds for words they are unable to locate. Choosing a different (real) word that begins with the same sound (clocktower – colander), one that is thematically connected to the first (letter – scroll), or one that is phonetically similar to the intended one (lane – late) are popular substitutions.

Deaf aphasia:

Numerous cases have demonstrated that deaf people experience some sort of aphasia. After all, it has been demonstrated that sign languages employ the same parts of the brain as spoken language. When an animal exhibits a certain behavior or observes another person performing in a similar way, mirror neurons are triggered.

These mirror neurons play a key role in enabling someone to imitate hand movements. Several of these mirror neurons have been found to be present in the Broca’s area of speech production, which explains the striking similarities in brain activity between vocal speech communication and sign language. People generate what other people see as emotional faces by moving their faces.

A more complete language is produced by fusing these facial expressions with voice, allowing the species to engage in far more intricate and nuanced communication. In addition to the basic hand movement method of communication, sign language also makes use of these face expressions and emotions. The same parts of the brain are responsible for these facial movement kinds of communication. Vocal modes of communication are at risk of severe kinds of aphasia when dealing with brain injury to certain locations.

These same, or at least very similar, types of aphasia can manifest in the Deaf community since sign language uses the same parts of the brain. Wernicke’s aphasia can manifest in people who use sign language, and they exhibit deficiencies in their capacity to generate any kind of expression. Some persons also exhibit Broca’s aphasia. It is extremely difficult for these people to sign the language concepts they are attempting to convey.

Severity of Aphasia:

The size of the stroke affects the type of aphasia and its severity. However, the frequency of a particular form of aphasia exhibiting a particular severity varies greatly. For example, aphasia of any kind can be mild or severe. People can improve regardless of the severity of their aphasia because of both treatment during the acute stages of recovery and spontaneous recovery. Furthermore, although the majority of research suggests that the best results for individuals with severe aphasia are achieved when treatment is given during the acute phases of recovery, Robey (1998) also discovered that individuals with severe aphasia can achieve significant language improvements during the chronic phases of recovery.

Regardless of how severe their aphasia may be, this research suggests that people with aphasia can nonetheless achieve functional objectives. Global aphasia usually results in functional language gains, albeit these gains may be delayed because it impacts several language domains. However, there is no clear pattern of aphasia outcomes depending solely on severity.

Causes of Aphasia?

The most frequent cause of aphasia is stroke, especially ischemic stroke that affects the dominant hemisphere inside the left middle cerebral artery’s (MCA) vascular region. According to a recent study, 30% of those who have had an acute ischemic stroke develop aphasia. Additional causes of aphasia include brain lesions, such as primary or secondary brain tumors, TBI, and neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s disease or frontotemporal dementia.

Unlike dysarthria, which is defined as articulation impairment, aphasia is always the consequence of an acquired brain damage. Diseases affecting the muscles, neuromuscular junction, or peripheral nervous system cannot induce aphasia.

Aphasia is caused by damage to the language center of the brain, which includes the parts of the brain involved in language.

- Stroke.

- Traumatic brain injury (TBI).

- Brain tumor.

- A brain infection.

- Brain inflammation.

- Alzheimer’s disease.

Other potential reasons are as follows:

- Aneurysms.

- Brain surgery.

- Cerebral hypoxia.

- Concussion.

- Congenital (present at birth) conditions.

- Epilepsy.

- Genetic conditions like Wilson’s disease.

- Migraines.

- Radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

- Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs).

The most common cause of aphasia is stroke; around 25% of people who have an acute stroke go on to develop aphasia. However, aphasia can result from any illness or injury to the brain regions responsible for language regulation. Brain tumors, severe brain damage, epilepsy, and degenerative neurological illnesses are a few examples of these. Rarely, herpesviral encephalitis can also cause aphasia. Aphasia may result from the herpes simplex virus’s effects on the hippocampus, subcortical regions, and frontal and temporal lobes. In acute conditions like stroke or brain trauma, aphasia typically appears rapidly. It progresses more slowly when caused by dementia, infections, or brain tumors.

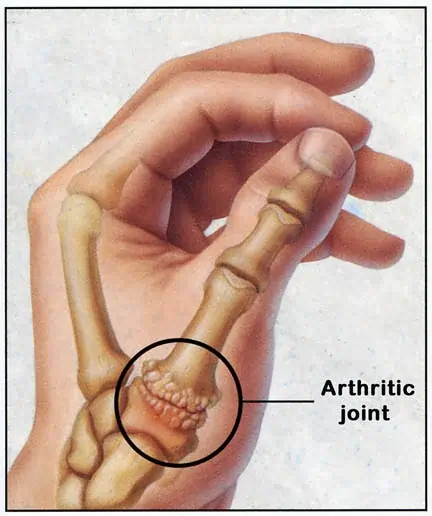

It is possible for aphasia to arise from significant tissue injury anywhere in the blue area. Damage to subcortical structures located deep inside the left hemisphere, such as the thalamus, the internal and external capsules, and the caudate nucleus of the basal ganglia, can also occasionally result in aphasia. The type of aphasia and its symptoms will depend on the location and degree of brain injury or atrophy. Damage to the right hemisphere alone can cause aphasia in a very tiny percentage of persons. According to some theories, these people may have had a unique brain structure before their disease or damage, possibly relying more on the right hemisphere generally for linguistic abilities than the general population.

Although its name may be deceptive, primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a kind of dementia that has some symptoms with a number of aphasias. It is typified by a progressive decline in language abilities while memory and personality, among other cognitive domains, remain mostly intact. PPA typically begins with an individual experiencing abrupt difficulties obtaining words, and then proceeds to a diminished capacity for creating grammatically accurate phrases (syntax) and decreased comprehension. It is currently unknown what causes PPA to start in those who are affected with it, however it is not caused by an infectious condition, stroke, or traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Temporary aphasia is another prodromal or episodic symptom of epilepsy. However, chronic and progressive aphasia may also result from recurrent seizure activity within language regions. Another uncommon adverse effect of the fentanyl patch, an opioid used to treat chronic pain, is aphasia.

Symptoms of Aphasia?

The type of aphasia you have determines the symptoms. However, the majority make it difficult to locate, comprehend, and identify various linguistic forms:

Finding the proper words, saying the wrong word, changing letter sounds, creating new words, repeating popular words or phrases, and uttering single words rather than complete sentences are all examples of difficulties with expressive language.

Language comprehension issues include difficulty following instructions, identifying the name of an object or the meaning of a term, understanding the specifics of a discussion, listening to multiple speakers at once, and failing to understand jokes or puns.

Reading and writing difficulties: not being able to spell words and construct sentences, use numbers (mathematics, counting money, or telling time), or comprehend written language (on signs, computers, books, etc.).

Any of the following behaviors can be experienced by people with aphasia as a result of an acquired brain injury; however, some of these symptoms may be caused by related or concurrent issues, such as apraxia or dysarthria, and not solely by aphasia. The location of brain injury can affect the symptoms of aphasia. People with aphasia may or may not exhibit signs and symptoms, which can vary in intensity and degree of communication disruption. People with aphasia frequently struggle to name things, so they may point at them or use phrases like “thing.” They might respond that a pencil is a “thing used to write” when asked to name one.

- Lack of linguistic comprehension

- Pronunciation difficulties that are not caused by weakening or paralysis of the muscles

- Unable to form words

- Anomia, or the inability to remember words

- Poor pronunciation

- Overuse and production of protologisms

- Not being able to repeat a phrase

- Perseverance is another name for the persistent use of the same syllable, word, or phrase (stereotypies, recurrent/recurring utterances, or speech automatism).

- Changing letters, syllables, or words is known as paraphasia.

- The inability to use proper grammar when speaking is known as agrammatism.

- Using fragments of sentences when speaking

- Not being able to read and write

- limited ability to speak

- Naming can be challenging.

- Speaking incoherently due to a speech impairment

- Unable to comprehend or follow basic instructions.

Related behaviors:

In light of the indications and symptoms mentioned above, people with aphasia frequently exhibit the following behaviors as an attempt to make up for speech and language impairments they have experienced:

- Self-repairs: Additional hiccups in fluent speech caused by ill-advised attempts to correct incorrect speech production.

- The challenge of non-fluent aphasias: After a life in which speaking and communicating flowed so naturally, a significant increase in expelled effort to speak might create obvious irritation.

- A behavior known as preserved and automated language occurs when some language or language sequences that were often utilized before onset are still produced more easily than other language after onset.

Subcortical:

The magnitude and location of the subcortical lesion determine the features and symptoms of subcortical aphasia. The thalamus, internal capsule, and basal ganglia are among the potential locations of lesions.

Cognitive deficits:

Although aphasia has historically been defined in terms of language impairments, there is mounting evidence that many aphasics also have non-linguistic cognitive impairments that co-occur in domains like learning, executive processes, memory, and attention. According to some theories, aphasia sufferers’ language impairment stems from cognitive deficiencies such working memory and attention. Others contend that while cognitive impairments frequently co-occur, they are similar to those shown in stroke victims who do not have aphasia and represent general brain dysfunction after trauma. Although cognitive brain networks have been demonstrated to facilitate language reorganization following a stroke, it is still unknown how much language impairment in aphasia is caused by attentional and other cognitive domain deficiencies.

Specifically, short-term and working memory deficiencies are frequently seen in aphasics. Both the verbal and visuospatial domains may be affected by these deficiencies. Additionally, these deficiencies are frequently linked to performance on language-specific tasks such discourse creation, lexical processing, sentence comprehension, and naming. According to other research, the majority of aphasics, though not all of them, exhibit performance deficiencies on attentional tasks, and their results are correlated with their language proficiency and cognitive abilities in other areas. Even individuals with mild aphasia who perform close to the ceiling on language tests frequently have delayed reaction times and interference effects in their ability to pay attention nonverbally.

Individuals with aphasia may have executive function deficiencies in addition to short-term memory, working memory, and attention problems. For example, initiating, planning, self-monitoring, and cognitive flexibility may all be impaired in aphasics. According to other research, individuals with aphasia complete executive function tests more slowly and inefficiently.

Cognitive deficiencies have a crucial role in the investigation and treatment of aphasia, regardless of their function in the underlying causes of the condition. For example, even more so than the severity of language abnormalities, the degree of cognitive impairments in aphasics has been linked to a lower quality of life. Additionally, the results of language treatment for aphasia and the rehabilitative learning process may be impacted by cognitive deficiencies. Although the results are inconclusive, therapies aimed at enhancing language proficiency have also targeted non-linguistic cognitive deficiencies. While some research has shown that cognitively-focused treatment can enhance language, other studies have shown little evidence that treating cognitive deficiencies in aphasics affects language results.

The extent to which cognitive tests depend on language skills for proper completion is a significant limitation in the assessment and management of cognitive impairments in aphasics. The majority of research has tried to get around this problem by assessing cognitive abilities in aphasics using nonverbal cognitive tests. It’s unclear, though, to what extent these tasks are actually “non-verbal” and not mediated by language. Using “real life” cognitive tests to measure non-linguistic performance, for example, Wall et al. discovered no relationship between language and non-linguistic performance.

Risk Factors

Any age can be affected by aphasia. It is more prevalent after age 65, particularly following a stroke or other brain-damaging event or condition. Following these incidents, aphasia may occur suddenly.

Diagnosis:

Following a physical examination and tests, a medical professional will make the diagnosis of aphasia. Your doctor will interview you about your symptoms and medical history throughout the examination. You may find it challenging to comprehend what your provider is asking you or to respond to these inquiries. Having a loved one or caretaker by your side during your exams might help you fill in the blanks if necessary.

Your healthcare practitioner can recommend that you see a speech-language pathologist (SLP) if they suspect aphasia. To find out more about your language comprehension (listening), speaking and conversational skills, idea expression, reading, and writing abilities, a speech-language pathologist will conduct a thorough examination. This aids in identifying the kind of aphasia you have.

In order to provide a comprehensive diagnosis, your healthcare professional will additionally assess the following factors:

- fluidity. Do you speak with ease and fluidity? Is the tempo, pitch, pronunciation, and grammar of your speech correct? Are you able to write effortlessly?

- Recognizing. Are you able to comprehend what others are saying? Do you use coherent sentences and phrases? Are you able to read and comprehend written language?

- Repetition. Do you find it difficult to repeat words, phrases, or entire sentences?

In order to diagnose aphasia or rule out illnesses that share similar symptoms, your provider will advise doing a number of tests. The results of the testing can possibly reveal the most effective medications.

Testing could involve:

- Blood tests.

- CT (computed tomography) scan.

- Electroencephalogram (EEG).

- Electromyogram.

- Evoked potentials test.

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scan.

The most widely utilized neuroimaging techniques for diagnosing aphasia and determining the degree of impairment in language loss are magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Finding the extent of lesions or damage inside brain tissue, especially in the left frontal and temporal regions where many language-related areas are located is accomplished by performing MRI scans. A language-related activity is frequently finished before the BOLD image is examined in fMRI research. Lower-than-normal BOLD responses can quantitatively demonstrate that the cognitive task is not being completed and show a reduction in blood flow to the affected area.

The use of fMRI, especially in aphasic individuals, has limits. Since a large number of aphasic people develop it as a result of a stroke, infarct a complete lack of blood flow may be present. Blood channel weakening or total blockage may be the cause of this. Because fMRI depends on the BOLD response (blood vessel oxygen levels), this is significant because it may result in a misleading hyporesponse during an fMRI investigation. Owing to fMRI’s drawbacks, such its reduced spatial resolution, it may appear that certain brain regions are not engaged during a task when, in fact, they are. Furthermore, as stroke is a common cause of aphasia, it can be challenging to determine the precise amount of brain tissue damage, which means that the impact of stroke-related brain damage on a patient’s functioning can vary.

According to a study on the characteristics linked to various disease trajectories in primary progressive aphasia (PPA) associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), metabolic patterns using PET SPM analysis can aid in forecasting the course of complete speech loss and functional autonomy in patients with AD and PPA. This was accomplished by contrasting the presence of a radioactive biomarker in brain MRI or CT scans with normal levels in individuals who do not have Alzheimer’s disease. Another condition that is frequently linked to aphasia is apraxia.

This is due to a subset of apraxia which affects speech. Specifically, this subset affects the movement of muscles associated with speech production, apraxia and aphasia are often correlated due to the proximity of neural substrates associated with each of the disorders. Researchers concluded that there were 2 areas of lesion overlap between patients with apraxia and aphasia, the anterior temporal lobe and the left inferior parietal lobe.

History and Physical Examination:

Determining whether a patient has aphasia, dysarthria, or dysphonia is the first step in examining them for speech issues. Dysarthria usually manifests as slurred speech and affects articulation but not comprehension, fluency, or expression. Hoarseness of voice is referred to as dysphonia. A comprehensive history and physical examination, with an emphasis on evaluating fluency, understanding, repetition, naming, reading, and writing, should be part of the clinical evaluation when a patient exhibits aphasia. Assessing the patient’s speech’s prosody, or musical quality, is also very important.

Asking the patient to follow instructions in one step, two steps, and finally three steps is how comprehension is evaluated. Clinicians are frequently able to correctly diagnose a variety of aphasic disorders by adhering to this methodical examination routine. Conventionally, these clinical aphasia disorders are categorized according to commonly recognized standards.

Lesions in the prominent peri-Sylvian region of the brain, which is located between the superior temporal gyrus posteriorly and the inferior frontal gyrus anteriorly, are linked to aphasia. As a result, patients frequently experience right hemiparesis, which mostly impacts the faciolingual regions. Right hemiparesis, which mostly affects the proximal muscles, is a common sign of transcortical global or transcortical motor aphasia, just like the symptoms of man-in-a-barrel syndrome.

Evaluation:

To determine the exact location and kind of the lesion, patients suspected of experiencing an acute stroke are usually assessed with a non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan and then an MRI. The patient is then evaluated by speech-language pathologists to pinpoint the precise regions and categories of language impairments. The Western Aphasia Battery and the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination are two official tests that can be used to diagnose aphasia.

While the Western Aphasia Battery assesses if a patient has aphasia and, if so, defines the type and severity of aphasia, the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination provides a severity assessment that ranges from mild to severe. It also establishes a baseline for subsequent evaluations, highlighting the patient’s strengths and shortcomings and assisting in the tracking of trends and advancements.

Four essential language assessment components are used in the evaluation of aphasia in order to distinguish between different aphasia syndromes: repetition, confrontational naming, understanding, and fluency of speech. Normal speech rate, intact syntactic ability, and effortless speech output are all considered aspects of fluency of speech. The comprehension test evaluates the patient’s capacity to comprehend spoken and written language. Finally, repetition assesses the patient’s capacity to mimic spoken or written language.

Fluent Aphasia Syndromes

- The hallmarks of Wernicke aphasia include fluent speech and poor comprehension. Patients display a range of paraphasic errors, such as neologisms, phonemic errors, and literal errors. This kind of aphasia is sometimes called word salad or jargon speech. Additionally, patients struggle with repetition and naming.

- Patients with transcortical sensory aphasia exhibit extraordinarily high repetition skills, which frequently lead to echolalia and perseverance, despite having fluent speech and reduced understanding.

- Patients with conduction aphasia are able to repeat words and speak clearly, but they also suffer from the usual phonemic paraphasia.

- Patients with anomic aphasia can correctly repeat words and speak with fluency and comprehension.

Nonfluent Aphasia Syndromes

- Speech that is nonfluent, telegraphic, effortful, and dysprosodic without paraphasic errors is a hallmark of Broca aphasia. Patients are unable to repeat, have varied degrees of anomia, and have intact understanding.

- The syndrome known as transcortical motor aphasia is characterized by nonfluent speech, complete understanding, and unusually good repetition, which frequently leads to perseverance and echolalia.

- Echolalia and perseverance are symptoms of mixed transcortical aphasia, which is characterized by nonfluent speech with poor understanding but extraordinarily good repetition.

- Global aphasia: This syndrome is characterized by nonfluent speech, poor comprehension, and difficulty repeating. Usually the consequence of an infarct in the prominent MCA zone, this is the most prevalent and severe type of aphasia.

Differential Diagnosis:

Aphasia can manifest subtly or acutely and can be caused by a number of illnesses that must be ruled out, such as stroke, brain tumor, brain hemorrhage, TBI, and dementia caused by toxins, infections, or vascular problems. Other differential diagnoses to take into account are:

- Stuttering can occasionally result from a dominant hemisphere stroke and can be linked to actual aphasia. Crucially, it is crucial to ascertain if stuttering started before to or following the acute brain injury.

- Altered mental state, which may be caused by delirium or encephalopathy.

- Dysphonia

- Dysarthria

- Apraxia of speech

- Cognitive-communication disorder

- Deafness.

Treatment of Aphasia:

To control your symptoms, your doctor will address the underlying cause of aphasia. Restoring blood supply to the affected part of the brain as soon as possible, for instance, might sometimes lessen or avoid irreversible damage if you have had a stroke. As your brain heals and you recover, the aphasia normally improves. Certain aphasia causes, like as concussions or migraines, are transient and do not require therapy.

Speech therapy can help you communicate more effectively if you have chronic or long-term brain injury. Your language comprehension is improved or restored through speech therapy, which also teaches you how to adjust to particular symptoms. Caregivers and loved ones can also participate in speech therapy so they can learn the best ways to interact with and support you.

Medications: The etiology of aphasia may be treated with medication. These differ greatly. Your doctor will suggest potential therapies based on your circumstances. Any underlying medical issues or preferences that can affect your care will also be taken into account.

Addressing the underlying cause of aphasia is the first step in treating it. Intravenous thrombolytic therapy with tissue plasminogen activator, tenecteplase (TNK), or intra-arterial mechanical thrombectomy are possible alternatives for patients who have experienced an acute ischemic stroke. Patients with brain tumors, TBI, or hemorrhagic stroke should have surgical decompression. Starting treatment with steroids, antivirals, or antibiotics may be required if the cause is an infection. Helping patients regain their maximum degree of independence is the main objective of aphasia treatment, despite the lack of a standardized approach. In order to do this, the patient’s physical comorbidities, mental health, and deficiencies must be addressed and managed. Additionally, social support and caregiver education have a big impact on how well a patient recovers.

It can be difficult for aphasic patients to express their needs and desires. Many people are aware of their shortcomings and situation, which can cause them to become frustrated, depressed, and less likely to attend therapy. As a result, treating aphasic patients efficiently requires an early diagnosis of depression. It is crucial to have emotional support from friends, family, and spiritual leaders. For assessment and treatment, referrals to a psychologist, neuropsychologist, or psychiatrist can also be required. Usually, pharmaceutical medication is part of depression treatment. Tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are examples of first-line drugs. However, because of their fewer negative impact profiles, SSRIs are typically recommended.

In order to create customized treatment plans, speech-language pathologists will evaluate patients to determine their strengths and shortcomings. Studies show that shorter, more focused treatment sessions result in greater improvement for patients than longer, less focused ones. Additionally, patients will get a variety of compensatory techniques, including alternative and augmentative communication. Whiteboards, pens, and paper for writing, photographs of everyday objects for identification, or more sophisticated gadgets like tablets with popular phrases or images on them are some examples of these tactics.

People who have nonfluent aphasias, like Broca aphasia, have trouble forming sentences fluently, although they can still sing. Melodic Intonation Therapy (MIT) uses rhythm and melody to improve a patient’s fluency. The fundamental idea of MIT is to minimize dependence on the dominant hemisphere while activating the intact nondominant hemisphere, which is in charge of intonation. Only patients with intact auditory comprehension can benefit from MIT.

The visualization of activation in the language regions of the brain is now possible thanks to advancements in neuroimaging technology, which helps advance the study and treatment of aphasia. Results from research on transcranial stimulation, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial electrical stimulation (TES), have been encouraging.

These methods have improved overall activity outcomes, functional capabilities, and word-finding abilities in addition to therapy. Because neuroimaging is costly and time-consuming, it is more appropriate for research settings than for clinical practice when it comes to determining the best stimulation locations for transcranial electrical stimulation (TES). On the other hand, auxiliary system stimulation is simpler to carry out and has demonstrated encouraging outcomes. Research on pharmacological treatment has produced conflicting findings, frequently occurring at the same time as acute stroke treatment. Although further research is needed, drug therapy, such as dopaminergic and catecholaminergic drugs, may promote brain plasticity and recovery.

Among the specific treatment methods are the following:

- Repetition and memory of specific words during copy and recall treatment (CART) may improve single word reading, writing, and naming as well as strengthen orthographic representations .

- Using index cards with symbols to represent different speech components is known as visual communication treatment, or VIC.

- People with global aphasia are usually treated with visual action therapy (VAT), which teaches them how to make hand motions for particular objects .

- The goals of functional communication treatment (FCT) are to enhance self-expression, social connection, and behaviors unique to functional duties.

- Promoting aphasic communicative efficacy (PACE) is a strategy for fostering regular communication between aphasics and medical professionals. This type of therapy places more emphasis on practical communication than on actual treatment.

- Individuals are urged to use drawings, hand gestures, or even pointing to an object to convey a specific message to their therapists.

- Melodic intonation therapy (MIT) seeks to support word retrieval and expressive language by utilizing the right hemisphere’s intact melodic/prosodic processing abilities

- The Centeredness Theory Interview (CTI) improves communication, cognition, and subjective well-being by incorporating client-centered goal development into the nature of present and intended patient encounters.

Prognosis:

Recovery from aphasia varies according to its kind, severity, etiology, patient motivation, and other elements. Recovery rates sharply decrease after the first two to three months following commencement, when the most improvement usually happens and peaks at six months. Global aphasia has a better prognosis for recovery than Wernicke aphasia, but Broca aphasia usually has better recovery rates than global aphasia.

Aphasia can occasionally be temporary and eventually disappear entirely. For others, if there is irreversible damage to the language area of the brain, aphasia could be a permanent condition. The effects of aphasia cannot be completely reversed, however speech therapy may help with its symptoms.

The brain goes through a number of healing and reorganization processes following a traumatic brain injury (TBI) or cerebrovascular accident (CVA), which may lead to better language function. They call this spontaneous recovery. The brain starts to rearrange and remodel in order to recover spontaneously, which is the natural recovery that occurs without treatment. The size and location of a stroke are two of the many variables that affect a person’s chances of recovering. It has been shown that education, sex, and age are not very predictive. Additionally, studies show that damage to the left hemisphere heals more quickly than to the right.

Your overall health and the reason of your symptoms are two of the many variables that affect your prognosis for aphasia. More details regarding your prognosis will be provided by your healthcare provider.

A full recovery is improbable if aphasia symptoms persist for more than two or three months following a stroke. It’s crucial to remember, though, that some people keep getting better over years or even decades. Improvement is a gradual process that typically entails teaching the person and their family compensatory communication techniques as well as assisting them in understanding the nature of aphasia.

It is challenging to forecast recovery since spontaneous recovery in aphasia is unique to each affected individual and may not appear the same in everyone. Wernicke’s aphasia patients may not develop as high a degree of speech abilities as individuals with milder forms of the disorder, despite the fact that some examples of the condition have seen better improvements than more moderate forms.

Complications:

Formerly educated and literate patients with aphasia may find it difficult to express their basic needs and desires. Many patients continue to be conscious of their shortcomings, which can cause annoyance and even hostility. They may feel alone and frequently feel like they have little control over their lives, which can lead to serious depression. Many people may also experience various impairments linked to cerebrovascular accidents, traumatic brain injuries, or comparable diseases, like diminished mobility, trouble performing everyday tasks, or even bedridden status.

Aphasia patients are more susceptible to infections or pressure sores because they may have bladder or bowel incontinence and be unable to express when they have urinated or defecated. They might also experience pain that is not adequately addressed. In general, the underlying cause of aphasia is frequently linked to its problems. Furthermore, a lot of aphasia patients often have co-occurring nonlinguistic cognitive impairments that impact both the verbal and visuospatial domains. These impairments frequently involve working memory and attention.

Prevention:

Since aphasia is unpredictable, it cannot be prevented. You can attempt to lower your chance of getting the conditions that cause it, though. Among the actions you can do are:

- Eating well-balanced meals and getting regular exercise. Many aphasia-causing disorders are related to heart and circulatory health. An excellent place to start is by taking care of your general health.

- Ear and eye infections require prompt care. These infections have the potential to prove fatal if they spread to the brain. Aphasia may result from brain damage caused by some illnesses.

- wearing protective gear.

- Brain injury can result from head injuries. Wearing safety gear can help you prevent an injury that could cause aphasia, whether you’re at work or on your own time. Helmets and seat belts (or other vehicle safety devices) are examples of safety equipment.

- Controlling underlying medical issues. Controlling long-term illnesses can help avoid complications that can lead to aphasia and brain damage.

Conclusion:

Getting a diagnosis of aphasia can be frightening and upsetting. You must rediscover the language skills you once mastered. Following a stroke or other brain injury, you could find it challenging to present at work or take part in a monthly reading club. Your social skills and mental health may suffer greatly as a result.

Although aphasia may resolve on its own, it can occasionally be a lifelong condition. Your medical professionals can assist you in adjusting, learning new communication techniques, and reestablishing or strengthening relationships with others.

FAQs

Does memory get affected by aphasia?

Later in their illness, a person with PPA may also exhibit additional symptoms, including as behavioral and personality abnormalities. cognitive and memory issues akin to those of Alzheimer’s disease.

Who is susceptible to aphasia?

Risk Factors

“Approximately 50 to 60 percent of my patients have experienced a stroke, but aphasia can also be observed in patients with neurological disorders, brain tumors, and traumatic brain injury.”

Is aphasia a sign of brain injury?

Aphasia is caused by damage to the language center of the brain, which includes the parts of the brain involved in language. Strokes are among the most frequent causes of aphasia. harm to the traumatic brain (TBI).

Does aphasia appear on an MRI?

Primary progressive aphasia can be diagnosed with the aid of a brain MRI. The test can identify brain shrinkage in particular regions. Additionally, MRI scans can identify cancers, strokes, and other disorders that impact brain function.

Is aphasia a result of elevated BP?

“Hemorrhage surrounding the brain, such as from a ruptured aneurysm or head trauma, can result in another kind of stroke.” Other medical disorders, such as uncontrolled diabetes or hypertension, can raise the chance of stroke and, consequently, aphasia in certain cases.

Is eating impacted by aphasia?

It impacts every stage of swallowing, including the pharyngeal (swallowing), esophageal (transit to the stomach), and oral (chewing) phases.

What is mistaken as aphasia?

A milder type of aphasia that affects language understanding only not expression is called dysphasia. However, the name dysphasia has been partially abandoned because it is frequently mistaken with dysphagia, a swallowing disorder.

What is aphasia near the end of life?

A compassionate and patient-centered approach is necessary while providing end-of-life care for a patient with aphasia. Both the patient and the caregiver may find communication difficult and frustrating if they have aphasia, a language condition that affects a person’s capacity to comprehend or express words.

Can someone with aphasia lead a regular life?

However, trouble finding words might continue for the rest of a person’s life even after obstacles have been conquered. Fortunately, they can succeed and achieve their objectives with the support of qualified experts and useful resources. Your relationships and social life may suffer as a result of aphasia.

What are aphasia’s last stages?

The progressive loss of language and speech in late-stage PPA usually causes very noticeable symptoms. Nearly all PPA patients eventually lose their abilities to read, write, and communicate. It becomes impossible to understand spoken language.

How is aphasia tested for?

To establish the existence of aphasia and choose the best language treatment plan, a speech-language pathologist can do a thorough language evaluation. The evaluation determines whether the individual is able to: Give common items names. Take part in a discussion.

Can stress create aphasia?

Stress doesn’t immediately produce anomic aphasic. On the other hand, persistent stress may raise your chance of stroke, which might result in anomic aphasia. Stress, however, may make your symptoms more apparent if you have anomic aphasia. Learn coping mechanisms for stressful situations.

What is aphasia’s primary cause?

Aphasia typically occurs abruptly following a head injury or stroke. However, a slow-growing brain tumor or a disease that causes progressive, irreversible damage (degenerative) might also cause it to develop gradually.

Is it possible to cure aphasia?

Without therapy, some aphasics recover completely. However, a certain degree of aphasia usually persists for most people. Over time, speech therapy can frequently aid in the recovery of certain speech and language abilities. However, a lot of people still struggle with communication.

How long can someone with aphasia expect to live?

According to scant data, people with primary progressive aphasia (PPA) often live for seven to twelve years after the commencement of their symptoms. PPA does not, however, seem to be a direct cause of death. Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is an uncommon neurological condition that entails the slow degradation of language skills.

What makes aphasia different from anomia?

The chronic inability to identify the correct term is known as anomia (literally, ‘without names’). Although anomia is a symptom of all types of aphasia, anomic aphasia is the term used to describe people whose main language impairment is word retrieval.

References

- Aphasia. (2024, December 19). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/5502-aphasia

- Wikipedia contributors. (2025b, February 15). Aphasia. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aphasia

- Aphasia – Diagnosis & treatment – Mayo Clinic. (2022, June 11). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/aphasia/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20369523

- What is Aphasia? – The National Aphasia Association. (2024, July 30). The National Aphasia Association. https://aphasia.org/what-is-aphasia/