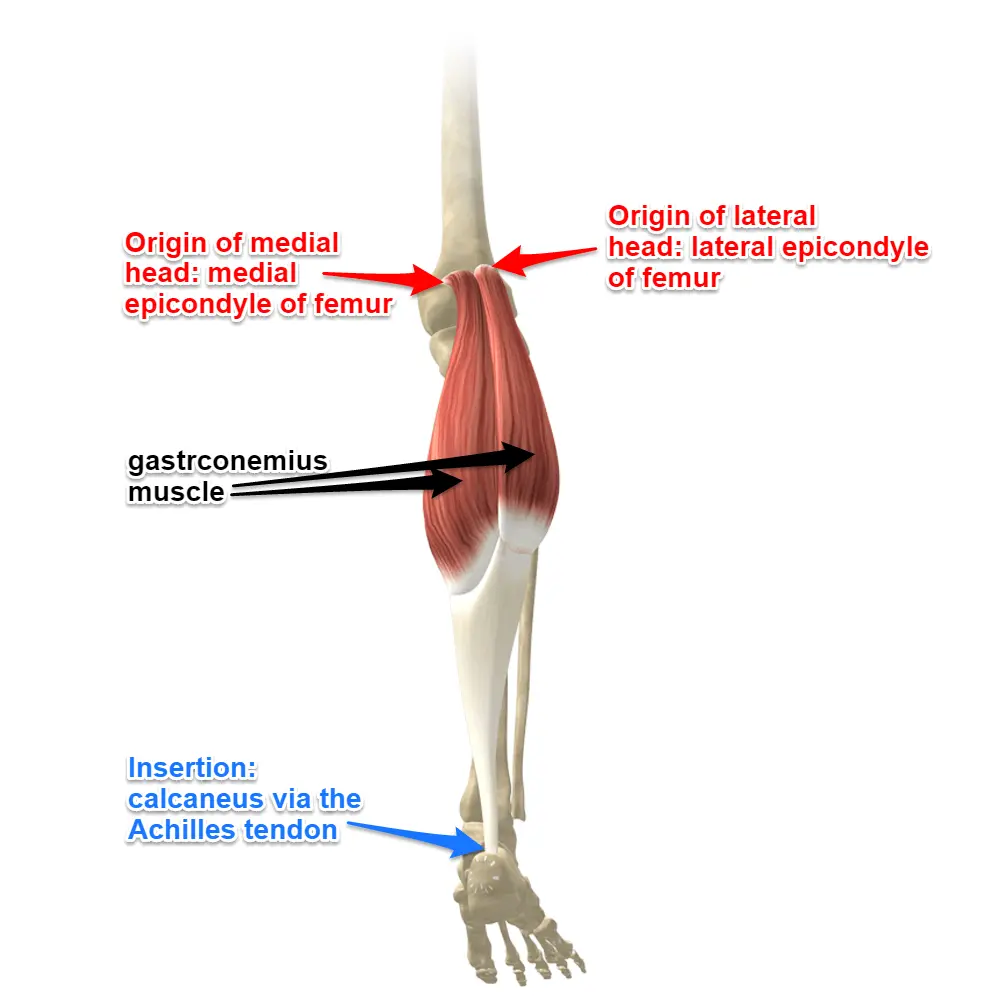

Anatomy of Gastrocnemius Muscle

The gastrocnemius is a large, two-headed muscle in the calf that forms the bulk of its shape. It originates from the femur and inserts into the Achilles tendon, working with the soleus muscle to enable plantar flexion of the foot and assist in knee flexion. It plays a crucial role in day-to-day activities such as walking, running, and jumping.

Origin

The gastrocnemius muscle, which forms a major portion of the gastrocnemius, has two heads of origin:

- Medial Head:

- The posterior aspect of the femur’s medial condyle is where the medial head originates.

- It also originates from the epicondyle of the femur.

- Lateral Head:

- This muscle has its origin on the lateral femoral condyle.

Insertion

- The two heads of the gastrocnemius muscle come together and form a tendon. This tendon then joins with the tendon of the soleus muscle (another gastrocnemius muscle) to form the Achilles tendon (also known as the calcaneal tendon). The Achilles tendon then inserts onto the posterior (back) surface of the calcaneus (heel bone).

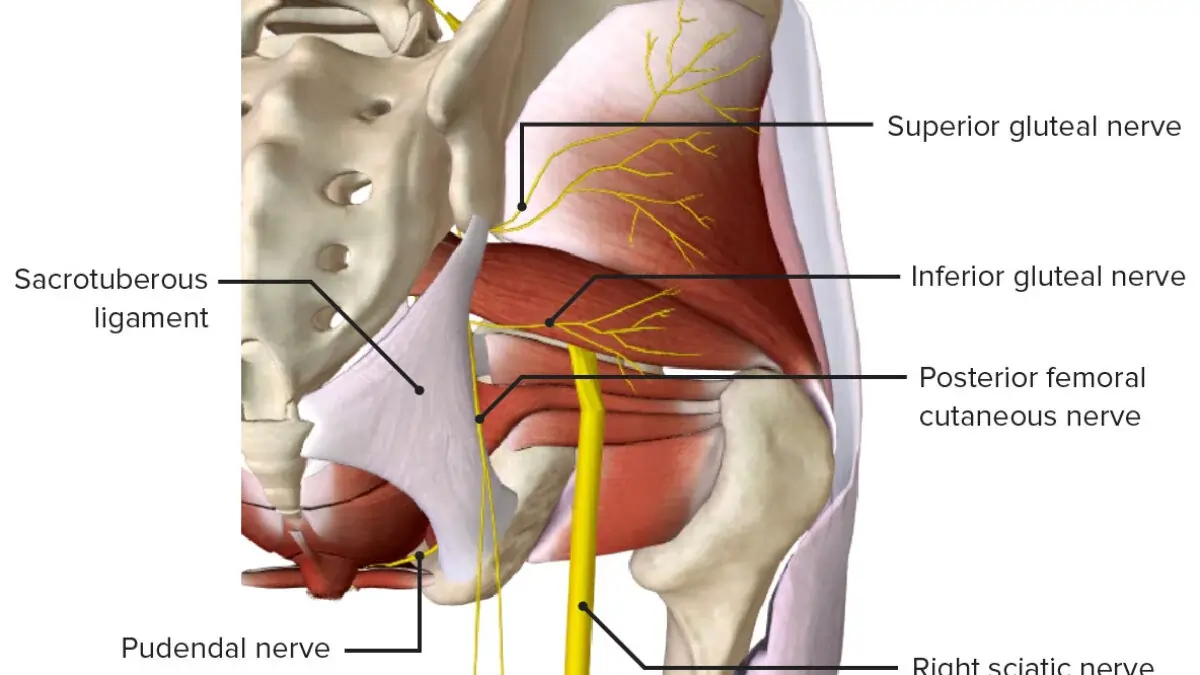

Innervation

The tibial nerve supplies the gastrocnemius’s two heads (S1 and 2).

L4, 5, and S2 are mostly responsible for cutaneous supply.

Blood supply

The lateral and medial sural arteries, which are direct branches of the popliteal artery, supply the medial and lateral heads of the gastrocnemius.

The popliteal fossa is where the arteries originate, however their level varies; typically, the lateral artery arises more distally and the medial sural artery more proximally. The superior genicular and popliteal arteries may also give rise to minor auxiliary sural arteries. The popliteal vein receives venous drainage via the lateral and medial sural veins.

Lymphatic drainage

Lymphatic drainage in the lower limb occurs via two distinct pathways: superficial and deep. The superficial vessels, located just beneath the skin, collect lymph from the skin and are categorized into medial, lateral, and superficial gluteal groups, all of which ultimately drain into the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

The deep lymphatic vessels, on the other hand, collect lymph from deeper structures such as bones, muscles, and joints. These vessels follow the path of the deep blood vessels and eventually terminate in the deep inguinal lymph nodes.

The lumbar lymph nodes, located in the lower back, serve as a major drainage point for lymph from various regions, including the lower limb, pelvic wall, perineal wall, and the sub-umbilical region of the abdominal wall. They also receive lymph from the vascular network supplied by the splanchnic branches of the aorta.

Functions

Half of the gastrocnemius muscle is made up of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. Its purpose is to flex the leg at the knee joint and plantar flex the foot at the ankle joint.

Running, leaping, and other “fast” leg motions are the main activities of the gastrocnemius, with walking and standing playing a smaller role. In contrast to the soleus, which has more red muscular fibers (type I slow twitch) and is the main active muscle when standing still, the gastrocnemius has more white muscle fibers (type II rapid twitch), which is linked to this specialization.

Exercises

Stretching Exercises of Gastrocnemius Muscle

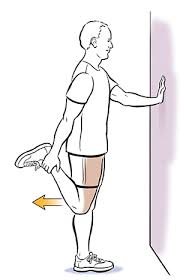

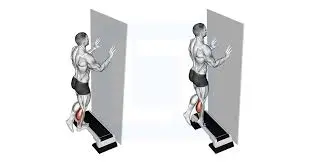

- Standing gastrocnemius Stretch:

- Place your feet shoulder-width apart and face a wall.

- Use the wall as a support by placing your hands on it.

- With one leg, take a step back while maintaining a straight knee and a grounded heel.

- Until your gastrocnemius starts to stretch, lean forward.

- Hold the stretch for 30 seconds, then release and repeat the stretch on the opposite side.

- Downward-Facing Dog:

- To start, go down on your hands and knees.

- Make an inverted V shape with your body by tucking your toes and raising your hips up and back.

- Maintain a tiny bend in your knees and an elevated heel.

- Alternately bend one leg at a time while gently pedaling your feet.

- For 30 seconds, hold the stretch.

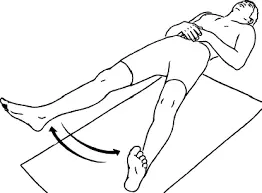

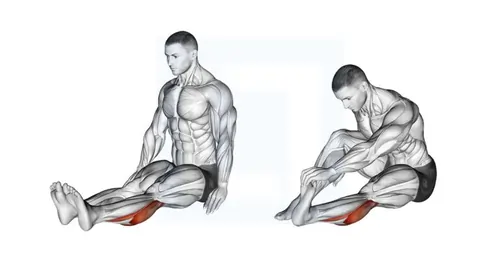

- Seated gastrocnemius Stretch:

- Sit down on the floor and extend your legs forward.

- Wrap a resistance band or cloth around your foot’s ball.

- While maintaining a straight knee, gently draw your toes towards you.

- Hold the stretch for 30 seconds, then release and repeat the stretch on the opposite side.

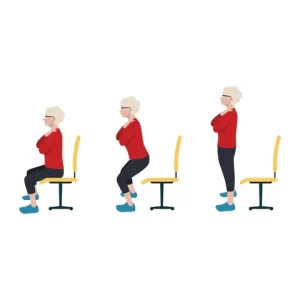

Strengthening Exercises

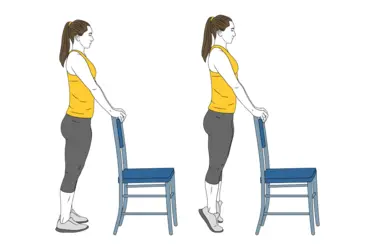

- Gastrocnemius Raises: The most basic and effective calf exercise. Stand with feet flat on the floor. Rise onto the balls of your feet, lifting your heels, and hold briefly at the top. Slowly lower your heels. For a greater range of motion, perform these on a slightly elevated surface (like a step). Increase difficulty by holding dumbbells or a weight plate.

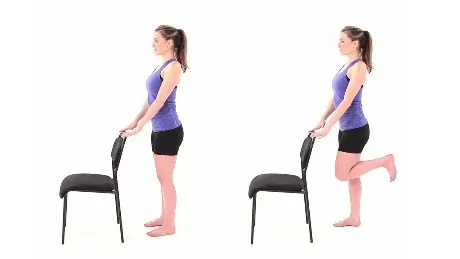

- Single-Leg gastrocnemius Raises: Perform gastrocnemius raises while standing on one leg. This increases difficulty and engages stabilizing muscles. Use a support for balance if needed.

- Jumping Rope: A dynamic exercise that works the calves and other leg muscles.

- Stair Climbs/Hill Sprints: Excellent for gastrocnemius development. Focus on pushing off with your toes.

Weighted Gym Exercises:

- Seated gastrocnemius Raises: This machine exercise effectively isolates the gastrocnemius (calf muscle). The seated position reduces the involvement of the soleus (another calf muscle), emphasizing the gastrocnemius.

- Standing gastrocnemius Raises (Machine or Smith Machine): Similar to bodyweight gastrocnemius raises, but with added weight for increased resistance.

- Leg Press gastrocnemius Raises: Perform gastrocnemius raises on the leg press machine by extending your ankles.

Muscles

The Myofascial Continuum

One should consider a myofascial continuum rather than a single area when discussing skeletal muscle. Through its fascial connections—the anatomical interconnections with other tendons (insertion and origin) and the fascia covering muscles—the gastrocnemius muscle stress is sent not only to the foot but also to the knee, hip, and lumbar region.

Hip anteversion may decrease due to malfunction in the hip’s physiological motions caused by a shortened gastrocnemius muscle.The force generated by the contraction of the muscle’s contractile component is fundamentally transmitted by the fascial system.

The connective tissue of the muscle stroma is the first tissue to experience the stress created by a muscle contraction. If the muscle has a fusiform architecture, the tension moves longitudinally down the fiber axis via the epimysium and up to the tendon.

The vector first travels in a transverse direction before subsequently following the epimysium’s longitudinal structures. If the muscle is pennate, such as the gastrocnemius, the force generated follows the interfilament inside the Z line of the sarcomeres, up to the sarcolemma, the extracellular matrix, and the epimysium (and thus the tendon).

Whereas the pennate muscles in the second scenario have a slower rate of force arrival to the tendons but a wider range of tension values, the fusiform muscles in the first scenario have a faster but less effective rate of force arrival. For instance, the gastrocnemius muscle is stronger than the soleus muscle, which is quicker but weaker, while the biceps brachii is faster but weaker than the deltoid muscle.

The longest and broadest tendon in the human body is the calcaneal tendon.The tendon’s attachment to the foot’s plantar fascia, which runs from the calcaneus to the metatarsal heads, is thought to be essential to the stability of the various tarsal joints. The plantar fascia’s tension is adversely affected by gastrocnemius muscle dysfunction, which modifies the foot’s physiological support.

Muscular Phenotypes

The soleus muscle is rich in aerobic or red fibers, whereas the gastrocnemius muscle is mostly composed of anaerobic or white fibers. This is another significant distinction between the two muscles. The gastrocnemius will be called upon to step in during an action that calls for the rapid expression of high strength. The soleus muscle will be the primary player if walking is the primary physical exertion.

Anatomical Variations

The human lower leg, like many parts of the body, exhibits fascinating anatomical variations. The gastrocnemius muscle, a key component of the gastrocnemius, is no exception. Beyond its typical structure, individuals may possess a “gastrocnemius tertius,” an additional muscle slip integrated within the gastrocnemius itself. Furthermore, an extra soleus muscle can also occur.

In rare instances, both these accessory muscles can be present simultaneously and on both legs (bilaterally), typically without impacting joint function or altering the tibial nerve’s innervation. However, the presence of a gastrocnemius tertius carries potential clinical implications. Specifically, it could potentially compress the popliteal artery within the popliteal fossa, leading to arterial entrapment.

Anatomical variations of the gastrocnemius muscle are well-documented. One such variant, the “quadriceps gastrocnemius,” has been described, though its functional and pathological significance remains unclear. Importantly, this variation is innervated by the tibial nerve.

Furthermore, the gastrocnemius can exhibit a range of anomalies beyond the presence of extra muscle slips. These include the absence of a head, particularly the lateral head, or variations in the origin of the muscle heads. A notable case report details a compression of both the popliteal artery and vein due to an atypical origin of the lateral gastrocnemius head. This anatomical anomaly resulted in the formation of arterial and venous thrombi, ultimately leading to secondary pulmonary hypertension.

Embryology

Skeletal muscle formation occurs during the eighth week of pregnancy. The paraxial mesoderm, which originates from the somites in the post-otic area, is the source of the gastrocnemius muscle. The myotomes, sclerotomies, and dermomyotomes of the somites vary.

The lateral dermatomyotome’s lips are the source of the muscles’ predecessors. Transverse striations, a common indicator of muscle maturity, are present in the last stage of muscle growth. Myotubes, the progenitor cells of muscle fibers, are present at this point.

Surgical Importance

Gastrocnemius muscle surgery carries inherent risks, notably the potential for sural nerve injury and suboptimal cosmetic outcomes. To minimize these risks and provide a structured surgical approach, the gastrocnemius region can be divided into five distinct anatomical levels:

- 1st Level (Distal): This level encompasses the calcaneal tendon’s insertion into the heel, including the portion within the heel itself.

- 2nd Level : This area involves the combined aponeurosis of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, extending proximally from the calcaneal tendon to the point where the muscle fibers transition into the aponeurosis.

- 3rd Level : This level begins at the musculotendinous junction, where the gastrocnemius muscle fibers merge with its aponeurosis, and extends distally to the point where the gastrocnemius and soleus fascial areas fuse.

- 4th Level : This level represents the muscular portion of the two gastrocnemius heads, located before the transition into the aponeurosis.

- 5th Level (Proximal): This level includes the origin of the two gastrocnemius muscle heads within the popliteal fossa.

This level-based approach provides a clear anatomical framework for surgical procedures, aiding in precise dissection and minimizing complications.

Gastrocnemius Muscle Flaps in Reconstruction:

The medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle offers a versatile, innervated flap for reconstructive surgery. This flap can address various clinical conditions, including:

- Foot drop

- Muscle defects in the upper limbs

- Volkmann’s contractures

- Tongue movement restoration

- Post-surgical infection management, particularly in knee prosthesis replacements, by promoting improved wound healing.

- Enhancing cicatrization in transtibial amputation procedures.

The use of a partial gastrocnemius muscle flap is favored due to its minimal associated complications and efficient surgical application.

Baker’s Cyst:

Named after surgeon William Morrant Baker, who first described it in 1877, a Baker’s cyst is a popliteal cyst arising from the knee joint. These cysts typically develop in the context of pre-existing knee pathologies, such as osteoarthritis or meniscal tears. These conditions lead to joint effusions that accumulate in the posterior knee region, specifically within the bursa of the medial head of the gastrocnemius.

Often, the cyst contains joint material that has migrated from the knee capsule, with fluid flow occurring unidirectionally. In most cases, Baker’s cysts are asymptomatic and are incidentally discovered during magnetic resonance imaging of a knee with known functional issues. Surgical excision, utilizing a posterior approach, is reserved for select cases.

Gastrocnemius Muscle Tears (Strains):

Muscle tears, or strains, are common injuries, particularly among athletes. The severity of a gastrocnemius muscle tear can be classified into three grades:

- First-Degree Strain:

- This is the mildest form, involving minimal muscle fiber damage (less than 5% of muscle mass).

- Muscle function is largely unaffected.

- Individuals may experience a persistent cramping sensation.

- Conservative treatment is indicated.

- Second-Degree Strain:

- This involves a more significant tear, resulting in noticeable pain, especially during movement.

- Conservative treatment is indicated.

- Third-Degree Strain:

- This is the most severe tear, involving at least 75% of the muscle mass.

- It is characterized by:

- Intense pain.

- Hematomas, edema, and significant swelling.

- Severe functional impairment, rendering the individual unable to move the leg.

- A palpable depression at the site of the tear, indicating the extent of the muscle disruption.

- This severe injury may require surgical intervention in some cases.

Achilles Tendon Disorders:

Achilles tendon (calcaneal tendon) disorders are prevalent injuries affecting both adolescents and adults, arising from both traumatic and non-traumatic causes. These disorders encompass a range of pathologies, including:

- Insertional tendinitis (inflammation at the tendon’s insertion point)

- Intra-substance tears and/or tendinopathy (degeneration within the tendon itself)

- Partial or complete ruptures

A significant challenge in Achilles tendon injuries is the potential for misdiagnosis. Acute ruptures are misdiagnosed in up to 25% of cases, with ankle sprains being the most common error. Delayed diagnosis can lead to chronic tendon dysfunction, making surgical repair more complex.

Key indicators of an Achilles tendon rupture may include:

- Sudden, acute pain in the calcaneal tendon.

- Functional impairment (inability to use the leg properly).

- A palpable gap or discontinuity in the tendon.

Diagnostic confirmation is typically achieved through ultrasound imaging.

Achilles tendon ruptures often result from chronic tendinitis that may have gone unnoticed or been underestimated. Contributing factors can include:

- Systemic diseases such as diabetes or lupus erythematosus.

- Chronic use of steroid medications.

These factors can alter the collagen fibers within the tendon, leading to an increase in type III collagen. This results in decreased tendon elasticity and reduced ability to withstand mechanical stress, predisposing it to rupture.

Achilles Tendon Rupture: Causes and Treatment

Achilles tendon ruptures are particularly common in athletes involved in jumping and running sports, such as basketball, soccer, and tennis. These injuries typically result from a sudden, forceful muscle contraction.

Treatment for a complete Achilles tendon rupture is generally surgical. Various tendon suture techniques are employed. Modern surgical approaches favor minimally invasive techniques, using small incisions to minimize scarring and reduce recovery time. In some cases, tendon reinforcement is performed using grafts from the gracilis, plantaris, or peroneus longus tendons.

Gastrocnemius Muscle Shortening (Equinus Deformity):

Gastrocnemius muscle shortening can arise from a variety of underlying conditions, including:

- Central or peripheral nervous system lesions.

- Hereditary muscle diseases, such as myopathies and dystrophies.

- Acquired diseases, such as diabetes.

The most prominent functional consequence of gastrocnemius shortening is equinus deformity, characterized by a plantarflexed foot (the foot pointing downwards) and a toe-walking gait.

Effective management requires a thorough evaluation to determine the underlying cause of the equinus deformity, assess its impact on gait, and develop an appropriate treatment plan. Treatment options include:

- Conservative methods:

- Physical therapy and stretching exercises.

- Orthotic devices (tutors).

- Botulinum toxin injections.

- Surgical methods:

- Calcaneal tendon lengthening.

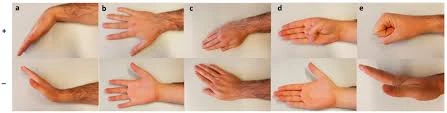

Silfverskiold Test for Equinus Deformity:

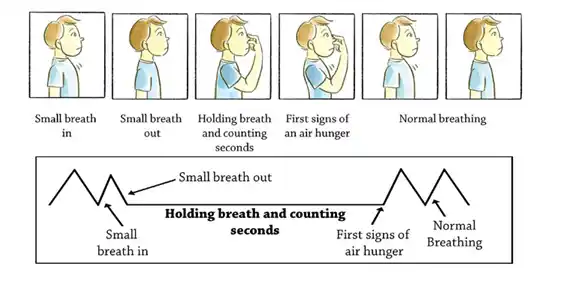

The Silfverskiold test is a valuable clinical tool for differentiating between gastrocnemius and soleus muscle contractures in equinus deformity. By assessing ankle dorsiflexion with the knee in different positions, the test helps pinpoint the primary muscle responsible for the limitation.

- Procedure:

- The test can be performed with the patient either sitting or supine.

- First, the examiner attempts to dorsiflex the ankle with the knee fully extended.

- The examiner attempts to dorsiflex the ankle with the knee flexed to 90 degrees.

- Interpretation:

- If ankle dorsiflexion improves significantly with the knee flexed, but is restricted with the knee extended, it suggests a gastrocnemius muscle contracture.

- If ankle dorsiflexion is limited in both knee flexed and extended positions, it suggests a soleus muscle contracture, or a combined gastrocnemius and soleus contracture.

Endoscopic Gastrocnemius Recession:

Modern surgical techniques for gastrocnemius recession utilize endoscopy to minimize collateral damage. This approach involves a small incision at level 4 of the leg, allowing for targeted release of the gastrocnemius muscle.

- Advantages:

- Reduced scarring compared to traditional open surgery.

- Decreased postoperative pain and faster recovery.

- Caution:

- Precise surgical technique is crucial to avoid excessive muscle elongation, which could lead to an iatrogenic overcorrection.

Clinical Importance

Tennis Leg

A frequent injury among tennis and squash players is tennis leg. When the myotendinous junction of the medial head of the gastrocnemius ruptures, it often manifests as an abrupt, acute pain toward the back of the gastrocnemius. Less frequently, it involves the plantaris muscle rupturing. It results by dorsiflexing the ankle and completely extending the knee, which overstretches the muscle.

Achilles tendon tendonitis

The calcaneal (Achilles) tendon thickening at its insertion causes Achilles tendonitis, a painful condition. The majority of those who experience it are middle-aged or older. It results in bone and cartilaginous metaplasia and is caused by repeated straining of the muscle. A bony growth at the tendon’s insertion onto the calcaneus and soreness in the rear of the heel are typical symptoms.

Achilles tendon rupture

Recreational athletes frequently sustain calcaneal (Achilles) tendon ruptures. The tendon’s calcaneal insertion, which is comparatively avascular, is typically 4-6 cm above the rupture, which can be partial or total. The patient may remember the sensation of the muscle rolling up their leg and the snap sound that occurs when a tendon ruptures. Excessive passive dorsiflexion and lack of plantar flexion against resistance are the results of a complete tendon rupture.

Calcaneal bursitis

Inflammation of the bursa, which divides the calcaneal tendon from the calcaneal tuberosity, a process of the calcaneus, is known as calcaneal bursitis. The back of the heel may experience discomfort as a result. Inflammation is frequently the result of long-distance running, basketball, and tennis, where the action of the tendon creates significant friction.

Gastrocnemius Muscle Muscle Pain

Several factors can cause pain in the gastrocnemius muscle (calf muscle). Muscle strain, the most common cause, happens when the muscle fibers are stretched or torn. Muscle cramps, which are sudden, involuntary muscle contractions, can also cause pain and are often linked to dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, or muscle fatigue.

Tendinitis, an inflammation of the tendons that connect muscles to bones, is another possibility and is frequently caused by overuse or repetitive movements.

Finally, although less common, deep vein thrombosis ( DVT ), a blood clot in a deep vein (usually in the leg), can cause gastrocnemius pain, often accompanied by swelling and redness.

Examination of Gastrocnemius Muscle

Silfverskiold Test:

The Silfverskiold test is a valuable clinical tool for differentiating between gastrocnemius and soleus muscle contractures in equinus deformity. By assessing ankle dorsiflexion with the knee in different positions, the test helps pinpoint the primary muscle responsible for the limitation.

- Procedure:

- The test can be performed with the patient either sitting or supine.

- First, the examiner attempts to dorsiflex the ankle with the knee fully extended.

- The examiner attempts to dorsiflex the ankle with the knee flexed to 90 degrees.

- Interpretation:

- If ankle dorsiflexion improves significantly with the knee flexed, but is restricted with the knee extended, it suggests a gastrocnemius muscle contracture.

- If ankle dorsiflexion is limited in both knee flexed and extended positions, it suggests a soleus muscle contracture, or a combined gastrocnemius and soleus contracture.

Endoscopic Gastrocnemius Recession:

Modern surgical techniques for gastrocnemius recession utilize endoscopy to minimize collateral damage. This approach involves a small incision at level 4 of the leg, allowing for targeted release of the gastrocnemius muscle.

- Advantages:

- Reduced scarring compared to traditional open surgery.

- Decreased postoperative pain and faster recovery.

- Caution:

- Precise surgical technique is crucial to avoid excessive muscle elongation, which could lead to an iatrogenic overcorrection.

FAQs

What are the other names of gastrocnemius ?

The calf muscle is also known as the sural muscle group.

The gastrocnemius is a major component of the sural muscle group, often referred to as the leg triceps. It’s a large, superficial muscle located on the posterior aspect of the lower leg, forming the bulk of the calf. The name “gastrocnemius” originates from the Greek words “gaster” (stomach or belly) and “kneme” (leg), reflecting its bulging shape.

Are the gastrocnemius muscles an extensor or a flexor?

As a biarticular muscle, the gastrocnemius functions as both a knee flexor and a plantar flexor, making it an antagonist during knee extension.

What signs indicate a weak gastrocnemius?

Reduced propulsion up and forward when walking and running is a sign of weak gastrocnemius muscles. Prolonged heel contact late in the stance phase of walking or running is the main gait abnormality caused by a weak gastrocnemius muscle.

Which exercises are beneficial for your gastrocnemius?

The traditional gastrocnemius-strengthening exercise is the gastrocnemius raise. The gastrocnemius and soleus muscles are toned and strengthened using your body weight. Better still, they don’t need much time and can be done anywhere. To gain equilibrium, stand close to a wall.

My gastrocnemius muscle hurts; why?

Numerous factors, such as injury, overuse, or other disorders, might cause pain in your calf’s gastrocnemius muscle.

Muscle strain injury

A torn gastrocnemius muscle can happen when you abruptly overstretch it, such when you run or leap.

Tears in the muscles

A muscle tear, either partial or whole, may result by abruptly overstretching the muscle.

Tendinopathy

Overuse of the muscle can result in microscopic rips in the tendon.

Overuse

Fatigue of the muscles: discomfort that may follow vigorous physical exertion or exercise

Overload of muscles: Pain that may arise from increasing the intensity of your workout, such as jogging farther or more frequently

Additional circumstances

Tightness: Muscle tightness caused by cramping or excessive usage

Vein varicosity: Prolonged standing or walking might cause thick, protruding veins.

Drugs: Some medicines, including those that decrease cholesterol, might induce discomfort in the calves.

Other conditions: gastrocnemius discomfort can be caused by conditions including peripheral artery disease (PAD), diabetes, liver illness, renal disease, or hypothyroidism.

How can discomfort in the gastrocnemius be stopped?

When a gastrocnemius issue initially appears, you should try to limit your activity but move as much as your symptoms permit over the first 24 to 48 hours.

When at rep?

ose, place your gastrocnemius in an elevated posture.

Every hour while you’re awake, take ten to twenty seconds to gently move your ankle and knee.

Don’t stand for extended periods of time.

Which stretch works best for the gastrocnemius?

Flexibility Stretch for the Gastrocnemius | Saint Luke’s Health System

Maintaining the left heel on the ground and the left leg straight, lean forward. Wait five to ten seconds. Do this two or three times, or as directed. Another method is to contract the gastrocnemius muscle pressing into the wall for five seconds while maintaining the stretch for five seconds.

Which deficit results in leg weakness?

Leg weakness may result from low potassium levels or deficiencies in vitamins B12, D, and magnesium. Intense physical exertion, peripheral vascular disease, and certain drugs are other potential reasons.

References:

- Gastrocnemius Muscle , Physiopedia , https://www.physio-pedia.com/Gastrocnemius

- Gastrocnemius Muscle , NCBI , https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532946/

- Physiotherapist, N. P.-. (2023, December 23). Gastrocnemius muscle Origin, Insertion, Function, Exercise. Mobile Physiotherapy Clinic. https://mobilephysiotherapyclinic.in/gastrocnemius-muscles-details/