Shoulder Joint

The shoulder joint, also known as the glenohumeral joint, is a ball-and-socket joint that involves the humerus (upper arm bone) and the scapula (shoulder blade). It is one of the most mobile joints in the human body, allowing for a wide range of movements such as flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, rotation, and circumduction.

Introduction

The glenohumeral joint, which is situated in the shoulder, can move in a wide variety of ways.

The shoulder is a significant anatomical structure and functional function due to its articulation at the glenohumeral joint, which makes it one of the most movable elements of the human body.

The shoulder girdle and the sternoclavicular joint, which connects the upper limb to the axial skeleton, are examples of this.

The shoulder joint’s large range of motion reduces joint stability and enhances the possibility of injury and dislocation.

The pectoral girdle and shoulder joint work together to provide flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, external/medial rotation, circumduction, and external/lateral rotation, among other upper limb movements. This is the joint that goes the most in the human body.

The lack of stability associated with the bony surfaces means that this shoulder function is compromised.

The muscles around the shoulder joint, the rotator cuff muscles, and the ligaments and tendons of the joint are all crucial to joint security.

One of the body’s most frequently damaged joints is the shoulder, due to its delicate balance between stability and motion.

Introduction of the shoulder joint in brief

| Type | There are essentially two kinds of synovial joints: multiaxial joints and ball and socket joints. |

| Articulating surface | Scapular glenoid fossa, glenoid labrum, and humeral head |

| Ligaments | Head of the Humerus, Glioid Fossa of the Scapula, and Glioid Labrum |

| Innervation | The nerves that make up the subscapular capsule, axillary nerve, and lateral pectoral nerve |

| Blood supply | The humeral arteries, both anterior and posterior, and the scapular and suprascapular arteries circumflexed |

| Movements | flexibility, flexion, lateral and internal rotation, circumduction, adduction, and abduction |

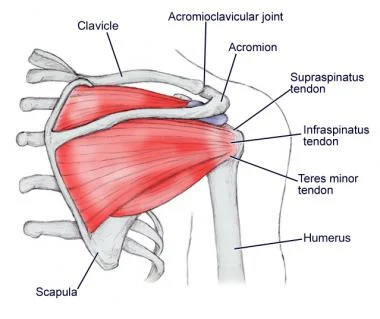

| Rotator cuff muscles | The rotator cuff muscles Shoulder Rotator Cuff: Subscapularis, Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, and Teres Minor Mnemonic SITS |

Shoulder Joint Anatomy

The shoulder joint performs as a multiaxial joint with diarthrosis, presently its structural definition is a synovial ball and socket joint.

Glene, which means “eyeball” in Greek, and the Latin term oid, which means “form of,” are the respective origins of the term “glenohumeral joint.”

The head of the humerus, or upper arm bone, and the glenoid cavity of the scapula, or shoulder blade, also undergo movement.

Given an extremely flexible joint capsule that forms a small interface between the two bones, the scapula is the most flexible joint in the human body.

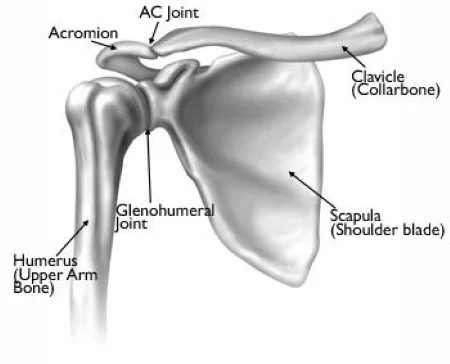

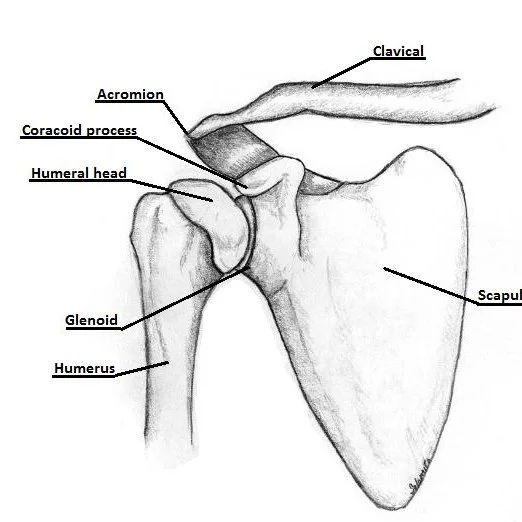

“Shoulder joints” refers to four different joints:

- A joint termed the glenohumeral conveys the scapular glenoid cavity and the humeral head.

- A structure made up of the clavicle and the scapular acromion together is dubbed the acromioclavicular (AC) joint.

- The areas in which the clavicle, sternum, or chest bone meet are termed sternoclavicular (SC) reunions.

- At the scapulothoracic joint, which is located close to the back of the chest, the scapula and ribs meet.

Bones & Joints of the Shoulder

- The clavicle is the collarbone.

- The only bone that joins the upper limb to the trunk is the clavicle.

- It has a soft S-shaped curvature and is felt all the way along.

- It consists of the shoulder girdle’s anterior portion.

- The scapular acromion articulates with the sternum, or chest bone, at the front of the clavicle.

- The connection that exists between the acromion of the scapula and the acromial end of the clavicle is represented by the shoulder roof.

- The scapula forms a broad, flat triangle bone that contains three processes: the coracoid, spine, and acromion. It makes up the shoulder girdle’s rear section.

- The scapula’s flat blade slides along the back of the chest to enable the arm to move in an extended manner.

- Ligaments and muscles follow the coracoid process, a thick, evolving part of tissue that extends from the scapula.

- An additional characteristic of the scapula is a small glenoid cavity that articulates with the head of the humerus and acts as a comma.

- The head, neck, ever greater tubercles, and shaft compose up the humerus’ upper end.

- The glenoid cavity receives the semispherical head projection.

- The humerus and the rotator cuff muscles are joined by prominent bones termed both the larger and smaller tubercles.

Structures of the Shoulder Joint

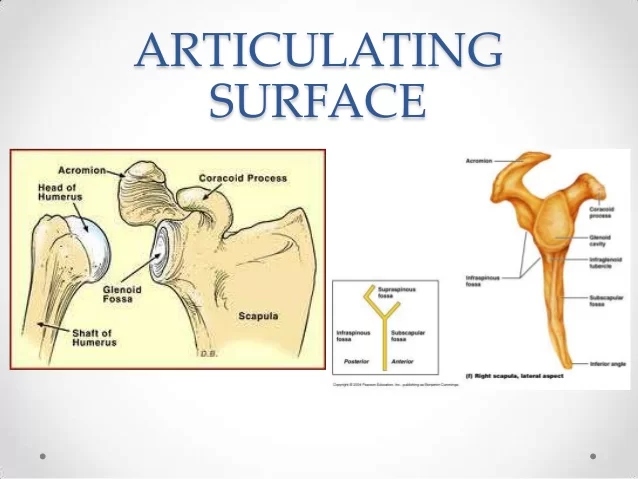

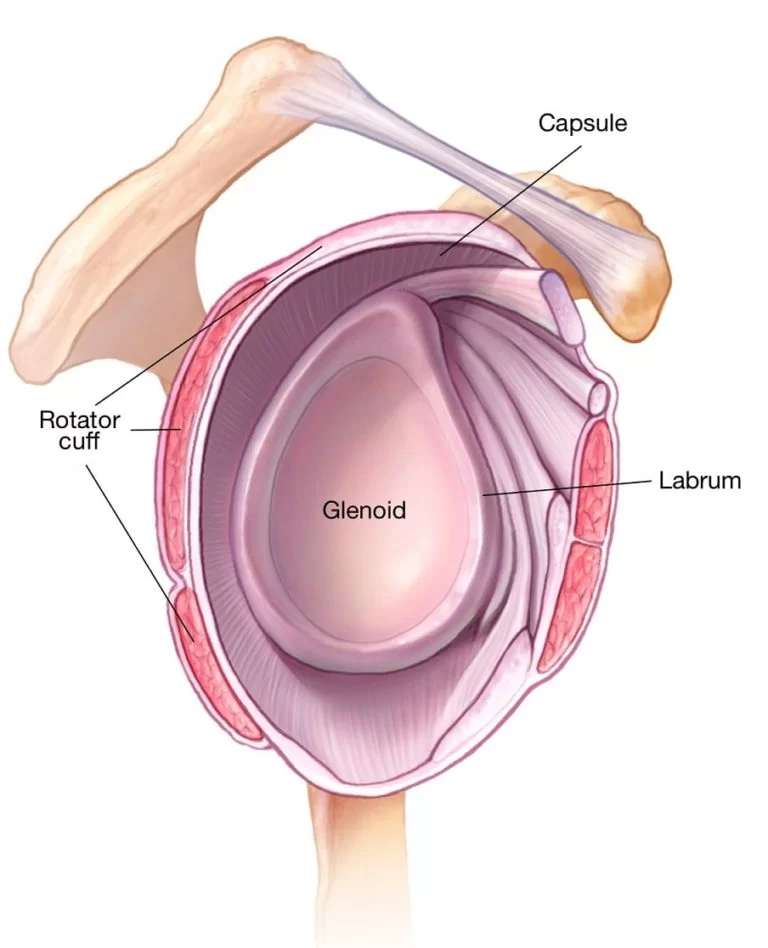

Articulating Surfaces

The articulation that happens between the humerus head and the glenoid depression, or fossa, on the scapula, is what makes the shoulder joint possible.

Even though the joint can move in a wide variety of directions, the humerus’s greater head than the glenoid fossa makes it inherently unstable.

The fibrocartilage rim called the glenoid labrum, which defines the glenoid fossa, assists in reducing surface disproportion.

The articular surfaces are not congruent because of the fossa’s less acute concavity relative to the humeral head’s convexity.

Due to the humeral head’s surface being three to four times greater than the glenoid fossa’s, the two structures never contact more than one-third of the humeral head.

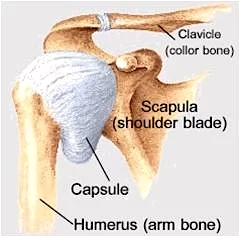

Joint capsule

- The shoulder joint has stability by fibrous tissue surrounded by a fluid capsule.

- A connective tissue reaching from the scapula to the humerus protects the joint.

- The capsule fuses to the humerus’s anatomical neck.

- only reaching its medial edge, the fibers sticking out by about a centimeter.

- It has two lines of attachment for the capsule on the scapula.

- The two examples of this are on the superior and posterior parts of the articulation, where the glenoid labrum and capsular fibers directly fuse.

- These intraarticular structures emerge as the capsule arches over the supraglenoid tubercle and its long head of biceps brachii muscle attachment.

- The capsule keeps its laxity to permit upper limb movement.

- The three glenohumeral ligaments thicken the anterior capsule, while the tendons of the rotator cuff muscles stretch over it and merge with its outside surface.

- The term rotator capsule refers to this continuous covering of tendons.

- The anterior subscapularis, posterior infraspinatus, teres minor, superior supraspinatus, and the long head of the triceps brachii make up this structure.

- This reinforced capsule has two weak areas.

- Its second, or inferior, capsular aspect shows a capsule’s weakest region.

- The arm that is abducted causes it to become strained and provides the least amount of support.

The capsule features two apertures:

- The tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii crosses between the humerus’s greater and lesser tubercles.

- via the glenohumeral joint cavity, the middle and superior glenohumeral ligaments, and the subscapular bursa.

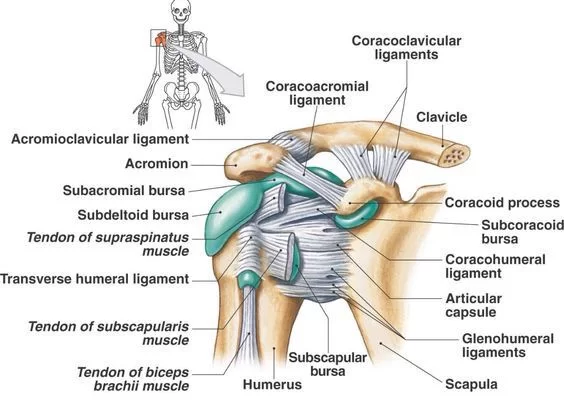

Bursa at the shoulder joint

A bursa provides a support mechanism for tendons and other joint parts.

The following bursae are crucial from a clinical standpoint:

Synovial fluid-filled bursae aid in facilitating joint mobility.

- The SASD bursa originates approximately at the supraspinatus tendon, which is found between the deltoid muscle and the acromion. When the subdeltoid subacromial bursa, also known as the subdeltoid bursa, is completely treated, the subacromial bone usually gets eliminated.

- The subacromial bursa eliminates friction beneath the deltoid, which enhances the rotator cuff tendon’s smooth flexibility. Shoulder pain may be brought on by subacromial bursitis, or bursa inflammation.

- Subcoracoid bursae are situated in an area between the coracoid process and the scapular capsule.

- The coracobrachialis and subscapularis muscles can be separated from one another by the coracobrachial bursa.

- The bursae facilitate smoother transitions between the components of the shoulder joint.

- The subscapular tendon and the scapula are separated by the subscapular area.

Shoulder labrum

The glenoid cavity and shoulder socket are protected by the labrum, a firm, smooth band of cartilage that gives the joint support.

- Hold the humerus’s head in position.

- Examine whether the ball-and-socket joint moves smoothly.

- The shoulder labrum can suffer from strains or injuries due to aging, severe use, or acute injuries.

Ligaments of Shoulder Joint

- There are similarities to these ligaments in phrases such as “glenohumeral,” “transverse humeral,” and “coracohumeral.”

- Several ligaments that prevent humeral dislocation limit the GH joint’s range of motion.

- The coracohumeral bone gets involved in auxiliary ligaments, while the glenohumeral and transverse humeral bones have roles in capsular ligaments.

The transverse humeral ligament

- The humerus and the rotator cuff muscles are united by the prominent structures called the large and smaller tubercles.

- The intertubercular sulcus, which moves challenging, gives support for the biceps brachii muscle’s long-head tendon.

The coracohumeral ligament

- The superior side of the joint is given stability by the ligament termed the coracohumeral ligament (ligamentum coracohumerale). The humeral tubercles and the transverse humeral ligament are found where they arise from the coracoid process of the scapula.

- It prevents the humerus from rotating too outward and translating poorly.

glenohumeral ligaments

- The superior, middle, and inferior glenohumeral ligaments distribute stability to the joint’s anteroinferior side.

- They each work to restrict the maximum amplitude of specific arm movements, providing a meager stabilizing effect;

- When the humerus rotates in an exterior (lateral) direction, all three ligaments stiffen, and when it rotates internally (medially), they relax.

- Another point of contention is the humeral head’s anterior translation.

- A diminution in length happens as the inferior and intermediate ligaments compress and the superior ligament relaxes.

The superior glenohumeral ligament

- From the scapula’s supraglenoid tubercle to the proximal part of the humerus’s lesser tubercle, the superior glenohumeral ligament stretches.

- Particularly with the proper humeral ligament, it protects the rotator interval and keeps the humeral head from translating inferiorly, particularly during shoulder adduction.

The middle glenohumeral ligament

- The middle glenohumeral ligament attaches to the scapula approximately below the superior GH ligament at the anterior glenoid border.

- It reaches the humerus’s smaller tubercle.

- This substantial ligament attaches and resides far below the subscapularis muscle tendon.

- Usually, when the arm is abducted (between 45 and 60 degrees), it stabilizes the anterior capsule, trimming external rotation.

The inferior glenohumeral ligament

- The anteromedial area of the humeral neck and the glenoid labrum house the inferior glenohumeral ligament, so known because of its sling-like form1.

- Given its greater thickness and length than the other two, this GH ligament is the strongest.

- Both bands help the humeral head when the arm is abducted past 90 degrees.

- Arm internal rotation is prevented by the posterior band while outward rotation is lessened by the anterior band.

Coraco–clavicular ligament

- The coracoclavicular ligament relates the scapula’s coracoid process to the clavicle for stability.

- They cooperate with the acromioclavicular ligament to preserve the clavicle’s position concerning the scapula.

- Although these ligaments are quite strong, they can rupture as part of an acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) injury when subjected to strong forces, such as those that occur after a high-energy fall.

- If an ACJ injury is severe enough, surgery may be necessary to restore the coracoclavicular ligaments.

coracoacromial ligament

- The other major ligament is called the coracoacromial ligament.

- It forms the coracoacromial arch and moves between the scapula’s acromion and coracoid process.

- This structure prevents the humeral head from moving superiorly because it lies over the shoulder joint.

Spaces in shoulder joint:

Important areas for joints are:

- The glenohumeral gap is typically 4-5 mm.

- An X-ray of the supraspinatus flow view shows the subacromial space measurement.

- In men, this area is noticeably larger and becomes somewhat smaller as one age.

- Less than 6 mm in the middle age range is considered abnormal and might be a sign of a ruptured supraspinatus muscle tendon.

- From an anatomical standpoint, the axillary gap is the distance between the shoulder-corresponding muscles.

- The axillary nerve and subscapular artery are transmitted through this area.

Function of the shoulder joint:

- The shoulder’s rotator cuff muscles provide a strong tensile force that aids in drawing the humerus’ head into the glenoid cavity.

- The goal of the glenoid labrum is to deepen and stabilize the shallow glenoid cavity.

- The shoulder joint is the most flexible in the body, with an independent flexion range of 120 degrees.

- The scapula goes from the rib cage to the humerus in a rhythm recognized as the scapulohumeral rhythm. It is a common technique that improves range of motion.

- Anything that alters the scapula’s position has the potential to impair this range.

- The big trapezius muscles, which stabilize the scapula, may not be balanced in some areas.

- This mismatch could affect the shoulder’s range of motion, which could lead to forward head carriage.

Muscles of the shoulder joint:

The intrinsic shoulder muscles are the humerus, which hooks to the clavicle and/or scapula. These include the following:

Deltoid

- Function:

- The medial bending and rotation of the arm are influenced by the anterior aspect.

- As the middle aspect accomplishes it allows the arm to be extended up to ninety degrees.

- The posterior portion is responsible for lateral rotation and leg extension.

- Origin: Scapular spine, acromion, and lateral clavicle

- Insertion: Tuberosity of the Deltoid

- Axillary nerve (C5, C6) innervation

Teres major

- Function: The arm’s adduction and medial rotation.

- Origin: The angle of posterior to inferior shoulder blade.

- Placement: Located on the medial part of the proximal humerus is the intertubercular groove.

- Innervation: C5, C6 lower scapular nerve.

Supraspinatus (Rotator Cuff)

- Function: Start the first 15 degrees of arm abduction, allowing the glenohumeral joint to stabilize.

- Origin: the sources are above the scapular spine, the supraspinous fossa, and the back scapula.

- Insertion: The more tubercle at the humerus’s highest point

- Suprascapular nerve innervation (C5, C6)

Infraspinatus (Rotator Cuff)

- Function: Stabilise the glenohumeral joint and rotate the arm laterally.

- Origin: under the scapular spine, in the inferior scapular fossa (posterior scapula).

- Insertion: A little insertion can be found in the humerus’s bigger tubercle and supraspinatus.

- Suprascapular nerve innervation (C5, C6)

Teres minor (Rotator Cuff)

- Function: Arm lateral motion, glenohumeral joint stabilization.

- Origin: The scapula’s inferior angle

- Insertion: Lower portion of the larger tubercle

- Axillary nerve (C5, C6) innervation

Subscapularis (Rotator Cuff)

- Function: The arm’s adduction and rotation to the medial side improve the glenohumeral joint.

- Origin: The scapula’s anterior aspect

- Insertion: Humeral tubercle, less severe

- Subscapular nerves (C5, C6, C7) are innervated.

The following muscles are additionally involved in shoulder joint movement:

Trapezius

- Function:

- During arm abduction, upper fibers elevate and rotate the scapula (90–180 degrees).

- The intermediate fibers retract the scapula.

- Lower fibers pull the shoulder blade inferiorly.

- Spinous processes C7–T12, the nuchal ligament, and the skull were the genesis of this statement.

- Insertion: scapular spine, acromion, and clavicle

- Innervation: C5, C6 accessory nerve

Latissmus dorsi

- Function: The upper limb turns medially, adducts, and extends.

- Origin: The iliac crest, the thoracolumbar fascia, the inferior three ribs, and the spinous processes of T6–T12.

- Insertion: The humerus’s intertubercular sulcus

- Thoracodorsal nerve innervation (C6, C7, C8)

- Function: Raises the shoulder blades

- Origin: C1–C4 vertebral transverse processes

- Insertion: Scapula’s medial border

- Dorsal scapular nerve (C5) innervation

Rhomboid major

- Function: The scapula retracts and rotates.

- Origin: Spinous processes of vertebrae T2–T5.

- Insertion: Scapula’s inferior medial edge

- Dorsal scapular nerve (C5) innervation

Rhomboid minor

- Function: The scapula retracts and rotates.

- Origin: C7 to T1 vertebrae’s spinous processes

- Insertion: Scapula’s medial border

- Dorsal scapular nerve (C5) innervation

Serratus anterior

- Function: anchors the scapula into the thoracic wall and enables the arm to rotate and abduct (90–180 degrees).

- Origin: The top eight ribs are located on the side of the chest.

- insertion: Down the scapula’s anterior medial edge

- Long thoracic nerve innervation (C5, C6, C7)

Pectoralis major

Function:

- Ankle flexion and adduction are provided potential by the clavicular head.

- When the sternal head adducts, arm rotation takes place medially.

- Accessory for motivation

Origin:

- clavicular head: clavicle’s medial half

- The sternocostal head is a structure made up of the lateral manubrium, sternum, six upper costal cartilages, and external oblique aponeurosis.

- Insertion: The proximal humerus’s intertubercular groove on the lateral side

- both the left and right pectoral nerves (C6, C7, C8)

Pectoralis minor

- Purpose: Shoulder depression and scapular protraction

- Origin: Along the appropriate costal cartilages of the third, fourth, and fifth ribs

- Insertion: The coracoid mechanism

- Medial pectoral nerve innervation (C8, T1)

Subclavius

- Function: The clavicle’s depression and stabilization

- Initial rib: medially

- Placement: below, midway along the collarbone

- Innervation: Subclavius nerve innervation (C5, C6)

Coracobrachialis

- Function: Arm flexion and adduction

- Origin: Process of coracoid

- Placement: In the center of the humerus, on the medial side

- Musculocutaneous nerve (C5, C6, C7) innervation

Biceps brachii

Function: Prevents the shoulder from flexion, supination, and dislocation.

Origin:

- Brief head: coracoid mechanism

- Long head: The scapula’s superior labrum and supraglenoid tubercle provide the long head.

- Radial tuberosity of the forearm fascia and radius, or bicipital aponeurosis, is a problem that develops.

- Musculocutaneous nerve (C5, C6) innervation

Triceps brachii

- Function: Prevents shoulder dislocation and overuse on the forearm extensor muscles.

Origin:

- Lateral head: above the humerus’s radial groove,

- Medial head: underneath the humerus’s radial groove

- Long head: scapula’s infra glenoid tubercle

- Insertion: Ulna and forearm fascia’s olecranon process

- Radial nerve (C6, C7, C8) innervation

Movements of the shoulder joint

- It has three degrees of freedom of motion due to ball-and-socket joints (the average maximum glenohumeral active range of motion is mentioned in parentheses).

- Flexion (180°) – extension (60°)

- Abduction (180°) – adduction (40°)

- Internal rotation (90°) – external rotation (90°)

The circumduction movement is produced by combining these motions.

- The glenohumeral and scapulothoracic joints —the acromioclavicular, sternoclavicular, and scapulothoracic articulations—are essential to arm movements.

- The glenoid fossa’s location in the chest wall can be altered by these joints working together.

- Hence, movement arises at the glenohumeral joint and upper limb region.

- Flexion (180°) – extension (90°)

- Abduction (180°) – adduction (30°)

- Internal rotation (90°) – External rotation (90°)

Abduction and external rotation characterize the closed glenohumeral joint; abduction and horizontal adduction (40–50°) define the open or resting joint.

External rotation, internal rotation, flexion, and abduction are the joints’ capsular structures, in that pattern. The glenohumeral joint necessitates further accessory movements that include spin, roll, and glide.

- The muscles involved in extension are the latissimus dorsi, teres major, and posterior deltoid using the sagittal plane.

- The sagittal plane determines how the pectoralis major, coracobrachialis, and anterior deltoid flexion contribute to the upper limb’s forward movement.

- Abduction is the method of raising an upper limb out of the coronal plane.

- The following 15 to 90 degrees are determined by the deltoid’s main fibers.

- The thumb points medially, and the subscapularis, pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, teres major, and anterior deltoid muscles rotate internally toward the midline being stretched.

- Primarily in the infraspinatus and teres minor, an external rotation is a movement away from the midline and toward the thumb.

Mobility and Stability

Though it loses stability, the shoulder joint is the most movable in the body. We’ll talk about the elements that support joint structure and those that allow mobility in this section.

The following elements support mobility:

- Joint type: ball and socket joint.

- The glenoid cavity is shallow and the humeral head is large, culminating in a 1:4 disparity of the bone surfaces. The golf ball and tee is an analogy that is frequently used.

- joint capsule’s inherent flexibility.

The following elements support stability:

- The rotator cuff muscles connect to the tuberosities of the humerus and connect with the joint capsule to encircle the shoulder joint.

- Due to these muscles’ resting tone, the humerus head presses towards the glenoid cavity.

- Glenoid labrum: the fibrocartilaginous ridge that surrounds the glenoid hollow. Closing the opening and deepening the hollow with the humeral head, decreases the possibility of dislocation.

- The coracoacromial arch forms and the joint capsule is strengthened by ligaments.

- To help provide stability, the biceps tendon functions as a small humeral head depressor.

Innervation

Axillary nerve (Nervus axillaris)

The posterior cord of the brachial plexus grows into the subscapular nerve (C5–C6), which innervates the glenohumeral joint. Several sources provide the joint capsule;

- Blood and oxygen are supplied to the superior and posterior parts of the suprascapular nerve.

- The anteroinferior portion of the capsule is innervated by the axillary nerve.

- The anterosuperior portion of the rotator capsule is transmitted by the lateral pectoral nerve.

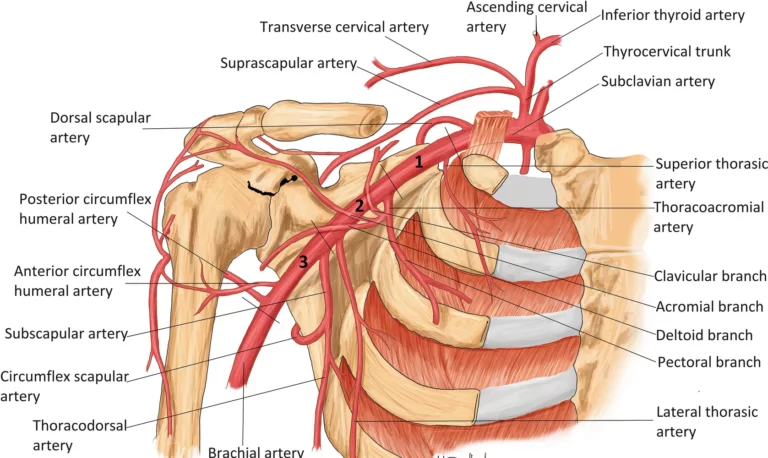

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

- Anterior and posterior circumflex humeral arteries arise in the axillary artery and deliver blood to the glenohumeral joint.

- The majority of the vascular blood supply to the humeral head is through the posterior humeral circumflex artery.

- As the arcuate artery, the ascending branch of the anterior humeral circumflex continues.

- It goes through and provides much of the humeral head through the bicipital groove. The subscapular arteries and their branches, a branch of the thyrocervical trunk, enhance the shoulder’s blood supply as well.

- These may be categorized into five primary types according to where they are located: pectoral, subscapular, humeral, central, and apical.

- This trunk will empty immediately into the thoracic duct on the left and right, respectively, or it will continue to enter the right venous angle.

- The extraction and analysis of axillary lymph nodes is often an essential process in the staging of breast cancer.

- However, lymphoedema, a disease where pooled lymph in the subcutaneous tissue causes severe upper limb swelling, might arise from the blockage of lymphatic drainage from the upper limb.

Nerves:

- The glenohumeral joint acts as a route for the axillary, suprascapular, and lateral pectoral nerves.

- The brachial plexus, a network of nerves made up of the ventral rami of the lower four cervical nerves and the first thoracic nerve [C5, C6, C7, C8, and T1], is where all of the nerves that supply the glenohumeral joint originate.

Clinical significance

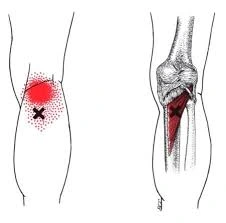

Rotator Cuff Injuries

- Roughly 18 million Americans experience shoulder pain each year, with rotator cuff injuries accounting for the majority of cases.

- Tears may be brought on by trauma, age-related degeneration, or excessive use. They can be asymptomatic or produce agonizing pain with restricted mobility.

- According to studies, smoking, high cholesterol, and a family history of tears are all risk factors for tears.

- Conservative, nonsurgical treatment is the primary line of treatment and may be helpful even with minor full-thickness tears.

- If not, or if the tears are more extensive, surgical repair is a dependable solution.

- The acromion’s pressure on the supraspinatus muscle tendon, which may culminate in inflammation of the tendon and the bursae about it, is the most typical cause of rotator cuff tendonitis/impingement.

Dislocations

- Glenohumeral joints are unstable and prone to dislocation, although they are the most active joints in the body.

- Of all the dislocations, 97% were anterior portion dislocations. They’re the most prevalent.

- Anterior dislocation is associated with fractures, axillary nerve injury, ripped ligaments, diminished cutaneous sensation over the shoulder, and paralysis of the deltoid muscle.

- The function of the axillary nerve typically recovers in patients who have had the humeral head reduced back into the glenoid fossa.

- Though less common, posterior dislocations are linked to seizures.

- With posterior dislocations as opposed to anterior, there is an increased risk of rotator cuff and ligament injuries.

- Particularly uncommon inferior dislocations happen due to hyperabduction.

Adhesive capsulitis

- Adhesive capsulitis, a synonym for frozen shoulder, affects 2 to 5% of people; the majority of sufferers are women and individuals over 55.

- Capsular fibrosis, adhesions, and initial difficulty are thought to be due to inflammation in the shoulder capsule region, which also lowers the decreased range of motion in all planes.

- Adhesive capsulitis is strongly linked to endocrine problems, including hypothyroidism and diabetes.

- Treatment is conservative and most cases resolve on their own.

- Refractory instances are only treated surgically, which releases the fibrotic capsule.

Osteoarthritis

- The shoulder joint is prone to articular cartilage degeneration due to wear and tear, just like other joints that receive a lot of use.

- Anatomical variables, age, gender, obesity, muscle weakness, and joint damage all increase the risk of developing osteoarthritis.

- When there is bone-on-bone contact, patients feel moderate to severe pain.

- To reduce inflammation, intra-articular corticosteroid injections may be necessary for patients with resistant osteoarthritis.

- Arthroplasts are surgical procedures used only in severe circumstances when medication cannot relieve symptoms.

Subacromial bursitis

- The painful inflammatory illness called subacromial bursitis frequently manifests as a constellation of symptoms called subacromial impingement.

FAQs

Which three shoulder joints are the important ones?

The humerus, or upper arm bone, the scapula, or shoulder blade, and the clavicle, or collarbone, are the three bones that compose the shoulder. The glenohumeral joint and the acromioclavicular joint, which grow within the clavicle, allow shoulder movement. It is the highest point of the scapula and the start of the acromion.

Which four muscles make up the shoulder joint?

The quadriceps, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor are the four muscles that include the rotator cuff. Support for the shoulder joint is given primarily by the rotator cuff muscles.

What is the shoulder’s main joint?

The glenohumeral joint, the primary joint, appears like a tree and a golf ball in shape. Adduction (arms across the body), extension (arms reaching back), abduction (arms to the sides), and forward flexion (arms in front) are among the actions for which it serves to give a broad range of motion.

What is the structure of the deltoid muscles?

The front delts that support arm forward motion are called anterior deltoids. Your body’s collarbone is where they connect. Lateral deltoids are the side delts that give support for sideways and upward arm movement. Arm retraction is assisted by the posterior deltoids, a group of back muscles.

What is the name of the shoulder bone?

The three bones that form the shoulder are the humerus, or upper arm bone, the clavicle, or collarbone, and the scapula, or shoulder blade.

What does a ligament do?

A ligament is an example of fibrous connective tissue that occurs between bones and helps stabilize and maintain things together.

References

- Miniato, M. A., Anand, P., & Varacallo, M. (2023, July 24). Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Shoulder. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536933/

- Image-Redirect Notice. (n.d.-n). https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fmobilephysiotherapyclinic.net%2Fshoulder-joint%2F&psig=AOvVaw1PW4N8uglR97L2QepHuXvV&ust=1718687361685000&source=images&cd=vfe&opi=89978449&ved=0CBEQjRxqFwoTCODF77_v4YYDFQAAAAAdAAAAABBx

- Image-Redirect Notice. (n.d.-o). https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fbangaloreshoulderinstitute.com%2Fstructure-shoulder-joint%2F&psig=AOvVaw1Fm1zuPt5zxwijgYnxjQrk&ust=1718687724314000&source=images&cd=vfe&opi=89978449&ved=0CBEQjRxqFwoTCOjs0-_w4YYDFQAAAAAdAAAAABAE

- Dhameliya, N. (2023, November 8). Shoulder Joint: Anatomy, Physiology, Movement, Exercise. Samarpan Physiotherapy Clinic. https://samarpanphysioclinic.com/shoulder-joint-movement/

- Physiotherapist, N. P. (2023, August 27). Shoulder Joint Anatomy (Glenohumeral)- Movement, Function. Mobile Physiotherapy Clinic. https://mobilephysiotherapyclinic.in/shoulder-joint/

- Shoulder joint. (2024, January 20). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shoulder_joint

21 Comments