Musculocutaneous Nerve Injury can result from various traumatic events, including direct trauma, compression, stretching, or iatrogenic causes such as surgical procedures. Depending on the severity and location of the injury, individuals may experience a range of symptoms, including weakness, sensory disturbances, and loss of motor function in the affected muscles.

The musculocutaneous nerve is the nerve that supplies the upper limb and controls motor and sensory functions. Damage to this nerve can cause a variety of problems that affect feeling and arm movement. The musculocutaneous nerve is one nerve that serves the upper limb and is susceptible to several types of injury.

The musculocutaneous nerve innervates the muscles of the upper arm and forearm, providing sensation and control over movement. Among these muscles are the brachialis, which facilitates elbow bending, and the biceps brachii, which are involved in elbow bending. This nerve can cause impairments to movement and sensation in the affected arm. This article describes the cause, its symptoms, and treatment for the musculocutaneous nerve injury.

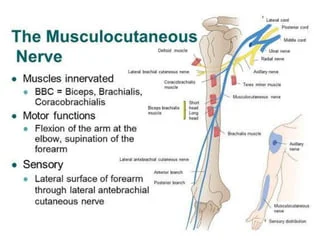

Anatomy of the Musculocutaneous Nerve

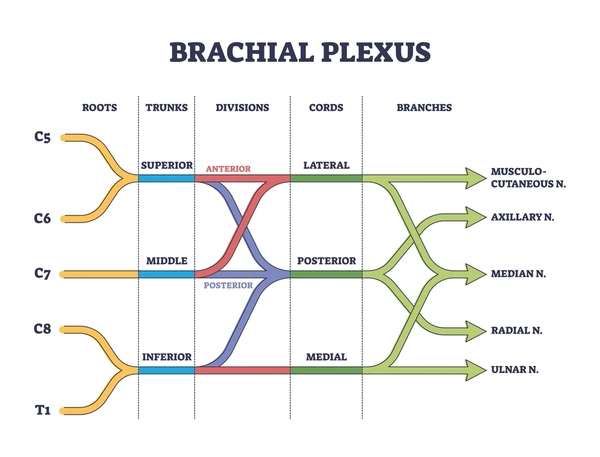

- The musculocutaneous nerve originates from the C5–C6 nerve roots and the terminal branch of the lateral cord of the brachial plexus. The pectoralis minor, a muscle in the upper chest that is located close to the armpit and shoulder, is where the musculocutaneous nerve begins. You call that part of your body the axilla. The coracobrachialis muscle, which connects the humerus bone to the upper arm, is where the nerve enters the arm.

- Then between the biceps brachii and brachialis muscles, it descends to the upper arm. The nerve in the elbow emerges close to the brachioradialis muscle and biceps muscular tendon after piercing the deep fascia, a type of connective tissue.

- The lateral cutaneous nerve then branches off and finishes at the wrist after running down the lateral side of the forearm. The musculocutaneous nerve can travel with the median nerve’s lateral head before returning it to the musculocutaneous nerve for communication.

- Its fibers are both motor and sensory. The lateral aspect of the forearm’s skin and the muscles in the front of the arm are supplied by it. The nerve travels between the brachialis muscle and the biceps, passing through the coracobrachialis muscle. After that, it pierces deep fascia to enter the elbow and gives rise to the forearm’s Lateral Cutaneous nerve. It provides sensory branches of the nerve below the elbow, but just motor branches above.

- The flexor muscles on the front side of the arm, the elbow joint, and the lateral side of the forearm are all supplied by the musculocutaneous nerve. The clinical relevance varies as well because of anatomical variances.

Root: C5, C6, and C7’s ventral rami.

Musculocutaneous nerve branches:

- Motor branches: The coracobrachialis, Brachialis muscle, Biceps Brachii Muscle

- Sensory branch: lateral cutaneous nerve reaching the back and front of the lateral forearm.

- Articular Branch: Elbow and Humerus Joints.

Functions of the Musculocutaneous Nerve:

The muscles in the upper arm receive motor function from the musculocutaneous nerve. It is referred to as the lateral cutaneous nerve when it enters the forearm and provides the sensory branch there.

Motor Function:

- Your arms can move because of the musculocutaneous nerve, which supplies the biceps, brachialis, and brachioradialis muscles. To produce the flexion movement of the arm at the elbow and shoulder, palm facing upward, similarly to a bodybuilder’s position, the musculocutaneous nerve collaborates with the biceps.

- In the upper arm, directly beneath the biceps muscle, is the coracobrachialis muscle. It is attached from the elbow to the shoulder. Muscle plays a small part in drawing the arm in towards the body and aids in shoulder flexion.

- The main muscle that assists in flexing the elbow is the brachialis muscle. It begins in the middle of the upper arm, beneath the biceps brachii muscle, travels past the elbow, and ends below the elbow joint, where it joins the ulna bone. The musculocutaneous nerve supplies the following muscles and their actions:

- The coracobrachialis stabilizes the humeral head in the glenoid fossa during free-side movement by flexion and adduction of the glenohumeral (GH) joint.

- The brachialis is an elbow joint flexion movement.

- Biceps Brachii: When the elbow flexes and retracts in response to weight, it stabilizes the glenohumeral joint.

Sensory Function:

- The lateral cutaneous nerve has several branches that reach the skin as it travels down the forearm and towards the wrist. The nerve supplies feeling to the forward part of your lateral part, extending from the elbow to the wrist, and the front half of your inner upper arm, extending from the elbow to the thumb’s base.

Anatomical Nerve Variation:

- There are various anatomical variants in the musculocutaneous nerve. It can attach itself to, cling to, and trade fibers with the median nerve in certain individuals.

- rather than passing through the coracobrachialis muscle, it runs under it.

What is the Musculocutaneous Nerve Injury

- The musculocutaneous nerve is a nerve located in the upper arm that provides sensory function to the lateral forearm and motor function to the biceps brachii and brachialis, two muscles involved in elbow flexion. Damage to this nerve can result in biceps muscle atrophy, numbness or tingling in the lateral forearm, and impairment in the elbow’s ability to bend.

- Severe brachial plexus trauma is frequently correlated with musculocutaneous nerve damage. Isolated musculocutaneous neuropathy can be brought on by trauma. Any vigorous exercise might cause this injury. Nerve damage is the cause of weak elbow flexion and supination movement. Sensation decreased on the forearm’s lateral side.

- The brachialis muscle is supplied by the radial nerve and the musculocutaneous nerve. One study found that the musculocutaneous nerve provides 42% of the muscle strength needed to flex the elbow.

Causes of the Musculocutaneous Nerve Injury

Multiple conditions can lead to damage to the musculocutaneous nerve. Here’s a more thorough explanation of the reasons:

Trauma:

- Penetrating injuries: These include shooting, stabbing, and other severe impacts that cause direct injury to the nerves in the armpit or upper arm.

Compression:

- Prolonged uncomfortable positions: This might happen when you’re sleeping and holding a heavy object for a long time. Tight bandaging can also compress a nerve.

- Repetitive stress: People who work in occupations involving repetitive arm motions or athletes who participate in sports like weightlifting or rowing that frequently need forceful elbow flexion are susceptible.

Accidental factors:

- Shoulder surgery: Because the nerve is vulnerable to compression or stretching during operations around the shoulder, especially when the deltopectoral technique is used, damage to the nerve may result.

Additional, less frequent causes:

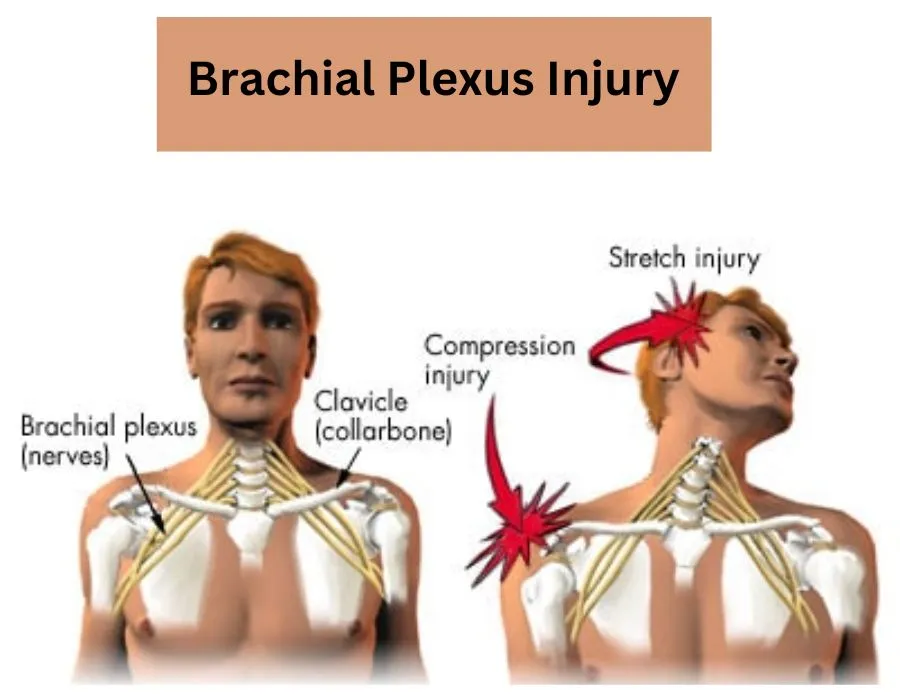

- Injury to the brachial plexus: Since the brachial plexus is the source of the musculocutaneous nerve, serious damage to this nerve network may also impact the musculocutaneous nerve.

- Anatomical anomalies: Occasionally, changes in the nerve’s path through the arm may render it more susceptible to damage or compression.

Symptoms of the Musculocutaneous Nerve Injury

Depending on how severe the injury is, musculocutaneous nerve injuries can present with a range of symptoms. Typical signs and symptoms include:

- Weakness in elbow flexion: This might make it challenging to raise objects, bend the elbow against opposition, or put your hand to your lips.

- The biceps muscle may atrophy, shrink, and weaken over time.

- Numbness or tingling on the lateral forearm: This could impair feeling from the elbow to the wrist in the region surrounding the outside of the forearm.

- Pain: The forearm, upper arm, or armpit may all experience pain.

Risk Factors of the Musculocutaneous Nerve Injury

- Trauma: Damage to the nerve can result from fractures, deep cuts, or penetrating wounds such as stabs to the armpit that affect the humerus and the upper arm bone.

- Compression: Damage to a nerve can result from sustained pressure on it. This can result from prolonged elbow bending when leaning on a hard surface.

- Repetitive stress: Players of sports involving repetitive forearm supination and elbow flexion are more vulnerable. This covers rowing, baseball, and weightlifting.

- Accidental injury: This can happen after procedures like intravenous line implantation or shoulder surgery.

- Specific medical disorders

- Osteoporosis, osteomalacia, and Paget’s disease are examples of metabolic illnesses that can weaken bones and raise the risk of fractures.

- Rheumatoid and osteoarthritis are two types of arthritis that can lead to inflammation and constriction of the area surrounding the nerve.

Diagnosis of the Musculocutaneous Nerve Injury

Physical examinations, medical histories, and occasionally further testing are used to diagnose musculocutaneous nerve injuries. Here is an explanation of the procedure:

Physical Assessment:

Initially, a physician will evaluate your symptoms and do a physical examination to look for:

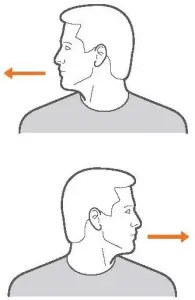

- Muscle weakness: Test your elbow bending capacity against resistance, paying special attention to your biceps muscle, to determine your muscle weakness.

- Atrophy: To determine whether there is any wasting or shrinking, the physician will examine and feel the biceps muscle.

- Sensory loss: Your lateral forearm, the region extending from the elbow to the wrist on the outside of your forearm will be tested by the physician.

Medical History:

The physician will look into the following aspects of your medical history:

- Recent injuries: Any deep cuts, fractures, or puncture wounds in the shoulder or upper arm that occurred recently.

- Repetitive activities: Engaging in sports or work that requires repetitive, hard elbow flexion and forearm supination are examples of repetitive activity.

- Previous surgeries: Shoulder and upper arm surgery.

- Medical illnesses that may be underlying: Diabetes, metabolic bone diseases, or other disorders that could raise the risk of nerve injury.

Additional Tests:

Although a physical examination and medical history are frequently adequate for a diagnosis, other tests could occasionally be required to verify the injury and determine the degree of nerve damage.

- The test known as electromyography (EMG) detects the electrical activity of the muscles and nerves. EMG can identify abnormal electrical activity in the biceps muscle, indicating nerve damage in the event of a musculocutaneous nerve injury.

- Studies on nerve conduction: This examination measures the speed at which nerve impulses pass through the damaged nerve. In this instance, it can evaluate the musculocutaneous nerve’s integrity and conduction speed.

- Imaging studies: To find fractures or other abnormalities in the bone that might be compressing the nerve, X-rays or MRI scans may be useful in certain situations.

Differential Diagnosis of the Musculocutaneous Nerve Injury

A musculocutaneous nerve injury might imitate other medical disorders’ symptoms. Through a procedure known as differential diagnosis, medical professionals examine multiple options to guarantee an accurate diagnosis and appropriate therapy. A physician may distinguish the following important disorders from a musculocutaneous nerve injury:

- Tendon injury or rupture in the biceps: This mostly affects the biceps muscle, which results in pain and weakness when bending the elbow. On the other hand, sensory loss (numbness or tingling) on the lateral forearm would not occur, in contrast to nerve injury. A biceps muscle belly bulge or bunching could be noticeable.

- Biceps or Brachialis Muscle Strain or Tear: Similar to a biceps tendon injury, a brachialis muscle strain or tear manifests as localized discomfort and weakness in the flexion of the elbow. The forearm’s sensory function would not be affected, either.

- C5 or C6 Radiculopathy: This is the term used to describe injury to the C5 and C6 nerve roots that leave the spinal cord in the neck. In the arm and forearm, it may result in weakness, discomfort, and sensory loss. But in addition to the biceps, there would be weakness in the shoulder and neck muscles as well.

- Damage to the Brachial Plexus: This is a more serious injury that affects the Brachial Plexus, the network of nerves supplying the entire arm. Along with other possible consequences, it would result in severe weakness, discomfort, and sensory loss throughout the arm and hand.

Treatment of the Musculocutaneous Nerve Injury

The source and extent of the damage determine the treatment plan for a musculocutaneous nerve injury. Below is a summary of the possible treatment modalities:

Conservative Management:

- Relax: Reducing activities that aggravate the injury promotes nerve healing. This may entail applying an elbow brace or sling for support.

- Physical therapy: A program can be created by a physical therapist to:

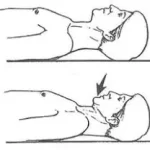

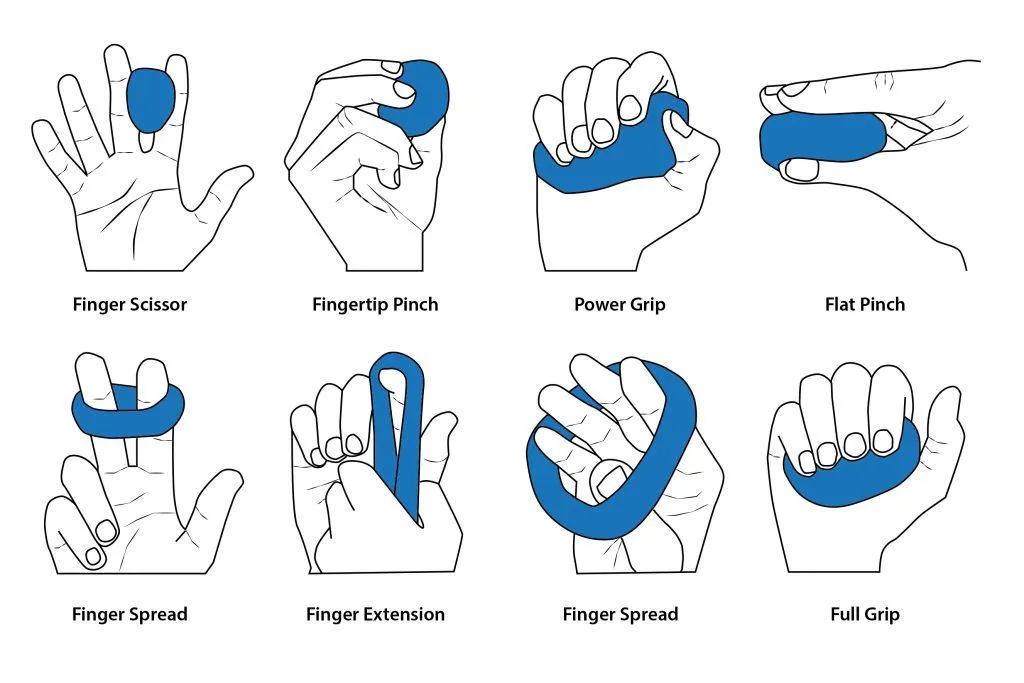

- Keep your range of motion intact: To avoid elbow joint stiffness and contractures, perform mild exercises.

- To make up for biceps weakness, strengthen the surrounding muscles by performing exercises that focus on unaffected muscles.

- Enhance proprioception, or bodily awareness, with exercises that help you remember where your arms and hands are.

- Pain management: Over-the-counter (NSAID) pain medications are one type of medication that can help control pain and discomfort.

Surgical Intervention:

When conservative treatment is unable to alleviate symptoms, surgery may be required in some situations. Surgery may be recommended if a reasonable trial of conservative therapy fails to provide noticeable improvement.

- Severe nerve damage: Surgery is required to heal a nerve that has been extensively injured or transected (cut).

- Nerve compression: Surgery is a viable treatment option if the nerve is being squeezed by scar tissue or other structures.

Surgical options could consist of:

- End-to-end Repair: When nerve ends are in good condition and closely separated, they can be sutured (sewn) back together.

- Nerve grafting: A healthy nerve segment from another area of the body can be used to bridge a substantial gap between the nerve ends.

- Nerve transfer: A healthy nerve from another area may occasionally be transferred to supply the muscles that the injured musculocutaneous nerve was initially responsible for innervating.

Rehabilitation:

- To ensure the best possible recovery after surgery, intensive therapy is required. To rebuild muscular strength, enhance coordination, and restore arm function, physical therapy is usually required.

Physical Therapy of the Musculocutaneous Nerve Injury

One of the most important aspects of musculocutaneous nerve damage rehabilitation is physical therapy. Here’s how physical therapists can be of assistance in more detail:

Evaluation & Assessment:

- Testing for muscular strength: The therapist will measure the brachialis, biceps, and other muscles used in elbow flexion.

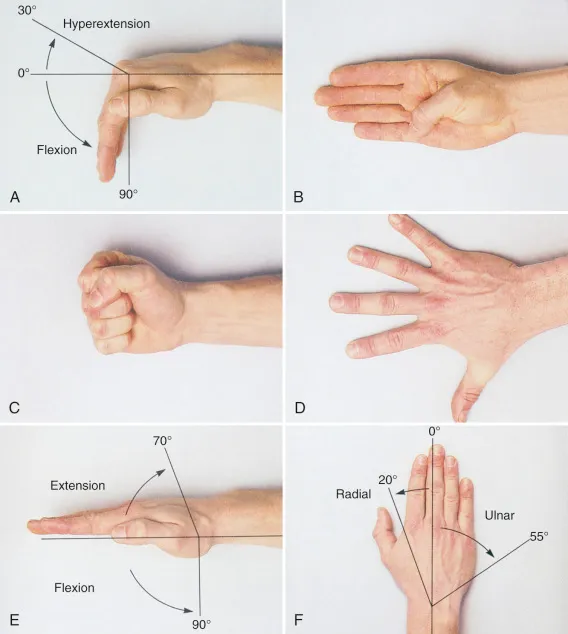

- Evaluation of range of motion: To determine any restrictions, the therapist will measure the elbow joint’s range of motion.

- Sensory testing: To ascertain the degree of nerve injury, the therapist will assess sensation in the lateral forearm.

- Gait analysis (if applicable): This may be required in extreme situations that impair coordination or balance.

Methods of Treatment:

- Rest and protection: To minimize physically demanding tasks that can exacerbate the nerve injury, the therapist might advise wearing an elbow brace or sling.

- Pain management: You can reduce pain and inflammation by using methods including electrical stimulation, ultrasound therapy, and applying heat or cold.

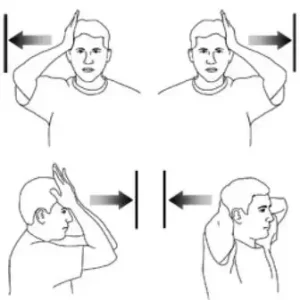

- Neuromuscular re-education: The therapist will lead you through activities to enhance muscle recruitment patterns and bring affected muscles back to normal operation. This could include:

- Passive exercises: Gentle motions carried out by the therapist to preserve joint mobility and avoid stiffness are known as passive exercises.

- Active-assisted exercises: These involve the patient trying a movement with the therapist’s help to progressively regain strength.

- Proprioceptive exercises: Exercises that promote body awareness and the perception of where an arm is in space are called proprioceptive exercises.

Techniques to Promote Nerve Healing:

- Electrical stimulation: Low-level electrical stimulation may be used to encourage neuron repair and enhance blood flow to the wounded location.

- Therapeutic ultrasound: This kind of ultrasound treatment can aid in tissue repair and inflammation reduction.

- Preventing Additional Damage:

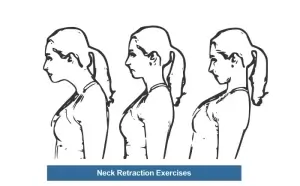

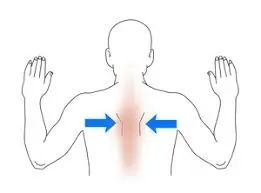

- Posture correction: Any imbalances in posture that may lead to nerve compression can be addressed by the therapist.

- Ergonomic education: To avoid aggravating the nerves more, the therapist might offer advice on how to adjust everyday activities and maintain good body mechanics.

Functional Training:

To enhance the capacity to carry out daily duties efficiently, the therapist will progressively add exercises that replicate daily activities as the patient makes progress. This could entail tasks like carrying groceries, dressing, or lifting goods.

Collaboration and Communication:

To guarantee a coordinated treatment strategy, the physical therapist will work in tandem with other medical specialists providing your care, including physicians and surgeons.

Additional Things to Consider About:

- Treatment duration: The length of physical therapy is contingent upon the severity of the injury and the progress made by the individual.

- Exercise program at home: To sustain and enhance the newly acquired strength and flexibility, the therapist will prescribe a customized program of exercise to be performed at home regularly.

- An effort is important: For the best chance of healing, regular attendance at physical therapy sessions and strict commitment to the prescribed program of exercise are essential.

Prevention of the Musculocutaneous Nerve Injury

The following actions can be taken to lessen the risk of musculocutaneous nerve injury:

- Adhere to proper posture: Prolonged slouching or relying on your elbows might compress the nerve.

- Good body mechanics: Use caution when lifting objects and stay out of uncomfortable positions that strain the shoulder and upper arm.

- Taking care of underlying issues: If you have diabetes or metabolic bone diseases, keeping these problems under control will help you avoid fractures and nerve damage.

- Appropriate training: To reduce nerve stress, athletes who participate in activities like weightlifting, baseball, and rowing that demand repetitive elbow flexion and forearm supination should adhere to correct training schedules and use the right equipment.

- Warming up and cooling down: To increase blood circulation and lower the chance of injury, always warm up before engaging in physically demanding activities and cool down afterward.

- Ergonomics: Consult an ergonomist to adjust your workstation and work practices to minimize stress on the nerve if your employment entails repetitive tasks or extended postures that strain the upper arm.

- Observing safety regulations: When using personal protective equipment (PPE), make sure it fits properly and follow workplace safety procedures to avoid incidents that could injure nerves.

- Exercise regularly: Maintaining muscle strength and flexibility through regular exercise helps lower the chance of injury.

- Keep your weight in check: Being overweight can exacerbate the pressure on your joints and nerves.

- Diet and nutrition: Consuming a well-balanced diet full of vital nutrients will help maintain nerve function and general health.

- Getting quick medical help: See a doctor right once if you sustain any injuries to your upper arm or shoulder, such as fractures, serious cuts, or penetrating wounds, to avoid complications including nerve damage.

FAQs

What signs and symptoms indicate an injury to the coracobrachialis?

This disorder is much less common than musculocutaneous nerve entrapment. A coracobrachialis tear can cause pain, stiffness, decreased strength, edema, and redness in the affected area.

Why does musculocutaneous neuropathy occur?

Why does musculocutaneous neuropathy occur?

Damage to the brachial plexus could do it harm.

Weightlifting and sports requiring a lot of forearm flexion and supination can cause Compression injuries.

Shoulder dislocation.

Surgery on the shoulders.

Entrapment of the elbow nerve.

How can pain from musculocutaneous nerves be treated?

Treatments for musculocutaneous neuropathy include splinting, physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, relative rest, and, in cases when conservative management is ineffective, surgical decompression.

What differentiates a musculocutaneous nerve?

The C5–C7 nerve roots give rise to the musculocutaneous nerve, which is the final branch of the brachial plexus’s lateral cord. It gives branches to the coracobrachialis muscle before entering it, which is the first muscle it penetrates.

References

- Musculocutaneous nerve. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Musculocutaneous_Nerve

- Desai, S. S., Arbor, T. C., & Varacallo, M. (2023, September 4). Anatomy, shoulder and upper limb, musculocutaneous nerve. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534199/

- Dellwo, A. (2022, February 27). The anatomy of the musculocutaneous nerve. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/musculocutaneous-nerve-anatomy-4782934

- Mbbs, L. K. (2019, August 8). Musculocutaneous nerve lesion (C5-C6). https://patient.info/doctor/musculocutaneous-nerve-lesion-c5-c6