Sternocostal Joints

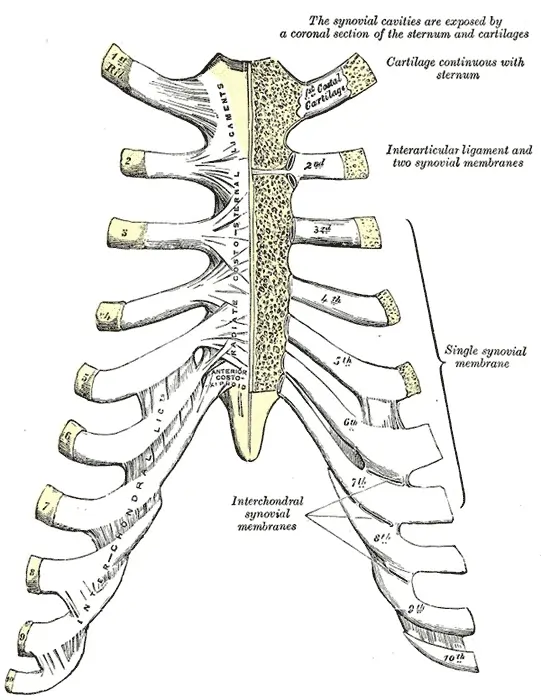

The sternocostal joints are the articulations between the sternum (breastbone) and the costal cartilages of the ribs. These joints are classified as synovial plane joints, except for the first sternocostal joint, which is a cartilaginous joint (synchondrosis).

They play a key role in the mechanics of breathing, allowing slight movements of the ribs during inspiration and expiration. Their flexibility and stability are essential for maintaining the rib cage’s structure and function.

Introduction

The thoracic costal cartilages (-chondral) and sternum (-sterno-) are joined by synovial plane joints known as chondrosternal or sternocostal joints. As a major cartilaginous joint, the first sternochondral joint is an exception.

The first sternochondral joint connects to the manubrium of the sternum, the next five attach mostly to its body, and the seventh sternochondral joint attaches to the xiphoid process. This total number of sternochondral joint pairs corresponds to the seven pairs of genuine ribs. Three ligaments—the intraarticular sternochondral, radiate sternochondral, and xiphichondral ligaments—reinforce these joints.

By allowing the costal cartilage to move with the ribs during inspiration and expiration, the sternochondral joint primarily facilitates mechanical breathing.

Articular surfaces

The term “sternochondral joint” refers to the intersection of the corresponding sternal ends of the first seven costal cartilages with the costal notches along the lateral border of the sternum.

From an anterior view, the sternal costal notches are visible as shallow, concave depressions on the sternum.The superior and inferior costal notches have different surface areas in the sagittal plane. The inferior costal notches eventually become more irregular and rectagular quadrilaterals, whereas the superior ones are spheroid or spherical. With its articular surfaces forming a sharp angle, the seventh costal notch is the deepest of all. The costal grooves’ edges are generally smooth, with a few tiny, uneven areas scattered throughout.

The costal cartilages’ sternal ends are big, convex, and nearly semiround in the coronal plane. Their size, surface area, and shape in the sagittal plane are comparable to those of the equivalent sternal costal notches. The first and seventh costal cartilages are the only two outliers; the former is somewhat less spherical and only slightly convex than the others, while the latter is pointed. The costal notches and costal cartilages may accommodate one another more easily because to these associated features, which provide a lock-and-key fit.

There is a difference between the second sternochondral joint and the others. Instead of being one continuous articular surface, the sternal articulation is a demifacet. This results from the existence of the sternum’s manubriosternal joint. The sternum’s manubrium has a superior articular surface that points inferolaterally and is beveled in the frontal plane.

The inferior articular surface of the sternum is a crescent-shaped circular depression on its body. It points in the frontal plane superolaterally. An intraarticular ligament separates the two compartments of the joint formed by the sternal end of the second costal cartilage, which resembles the demifacet in shape.

A comparable circumstance occurs at the seventh sternochondral joint. The xiphisternal joint, which has nearly the same articular surface features as the second sternochondral joint, makes it a demifacet as well. However, due to the absence of an intraarticular ligament, the seventh sternochondral joint only has one joint cavity.

Joint capsule

Synovial joints make up the second to seventh sternochondral joints. The sternochondral ligaments that surround them support the thin fibrous capsule that envelops them. A synovial membrane that serves as the lining of the fibrous capsule secretes a viscous lubricating fluid.

From the second to the seventh sternochondral joints, joint cavities are also present. But as people age, the thin cavities—particularly in the inferior sternochondral joints—usually go away. In these situations, intraarticular fibrocartilage takes the place of the destroyed joint cavities. The second sternochondral joint is an exception, with joint cavities that stay open even as people age. In every sternochondral joint, fibrocartilage lines the articular surfaces.

Instead of being a synovial joint like its neighbors, the first sternochondral joint is categorized as a primary cartilaginous joint (symphysis). As a result, there is no joint cavity between the cartilage and the corresponding costal notch on the sternum, and there is hardly any movement. The inferior sternochondral joints’ propensity to be more cartilaginous can also cause the seventh sternochondral joint to be symphysitic in some people.

Ligaments

There are multiple ligaments that support the thin fibrous capsules of the sternochondral joints, including the intraarticular, xiphichondral, and radiating sternochondral ligaments.

The anterior and posterior radiating sternochondral ligaments are two sets of broad, short, and thin ligaments. The anterior margins of the relevant costal notches of the sternal body and the anterior surface of the sternal ends of the costal cartilage are separated by the anterior ligaments. Their posterior equivalents are identical and are connected by the posterior ligaments.

Thus, both anteriorly and posteriorly, the radiating sternochondral ligaments directly reinforce the sternochondral joints. Connecting with the ligaments from the other side, the fibers of those ligaments extend over the sternal surfaces. In the process, they weave together with pectoralis major tendinous fibers to form the sternal membrane. All of the sternum’s joints are supported by this thick, fibrous, crisscrossed membrane, which is strongest inferiorly.

The second sternochondral joint has very different radiating sternochondral ligaments. Both the anterior and posterior ligaments adhere to more than just the sternum’s body; they also attach superiorly to the manubrium, horizontally to the manubriosternal joint’s fibrocartilage, and inferiorly to the sternum’s body.

Together, these horizontal fibers make up the intraarticular sternochondral ligament, which reaches the second costal cartilage’s sternal end. This intraarticular ligament limits the second sternochondral joint’s range of motion while also giving it additional support. The intraarticular sternochondral ligaments may also be able to attach the third sternochondral joints to the first or second sternochondral joints in some people.

That seventh sternochondral joint is the sole one reinforced by the xiphichondral ligaments. These ligaments come in two varieties: anterior and posterior. The anterior one is more prominent and connects the anterior margin of the seventh sternal costal notch on the xiphoid process to the anterior surface of the sternal end of the seventh costal cartilage. On the other side, the posterior xiphichondral ligament performs the same function.

Innervation

The anterior rami of spinal nerves T1 through T11 are represented by the intercostal nerves, which innervate the sternochondral joints.

Blood supply

Branches of the internal thoracic artery, which originates from the subclavian artery, provide blood to the sternochondral joints.

Movements

The initial sternochondral joint is categorized as a primary cartilaginous joint, or synchondrosis, both physically and functionally, because it lacks a joint cavity and has intraarticular fibrocartilage.

The joint is therefore nonaxial and allows for very little movement. During mechanical ventilation, this factor is crucial. This immobile sternochondral joint aids in the automatic upward and outward, or “pump handle,” movement of the sternum when the ribs rise and fall and their anterior ends elevate. Thus, during inspiration, the first sternocostal joint contributes to the thorax’s increased anteroposterior diameter. The opposite occurs when it expires.

For the remaining six sternochondral joints, the presence of a joint cavity and the articular surfaces make them structurally flat synovial joints. They only allow nonaxial, translational movements in terms of functionality.

During this uniplanar motion, the articular surfaces of the sternal costal notches and the corresponding sternal ends of the costal cartilages slide or glide linearly. The intraarticular sternochondral ligament restricts the second sternochondral joint’s range of motion even further. During mechanical breathing, the second to seventh sternochondral joints’ articular configuration makes thoracic movements easier.

The sternal ends of the costal cartilages slide superoinferiorly into the sternal costal grooves when the ribs rise and fall and the sternum revolves upward and outward (a movement known as the “pump handle”). The sixth and seventh ribs’ sternochondral joints allow the movement axis to pass through them, allowing for thoracic expansion as they likewise move laterally and outward (also known as “bucket handle” movement). During expiration, the anteroposterior and transverse thoracic diameters decrease, and the opposite occurs.

Muscles acting on the sternochondral joints

There is no direct muscle activation on the sternochondral joints. Their movements instead occur indirectly because of the sternum, costal cartilages, and true ribs.

Many muscles join to the ribs, but the breathing-related anterolateral trunk muscles are the most crucial. The transverse abdominis, rectus abdominis, quadratus lumborum, transversus thoracis, abdominal oblique (internal, external), and intercostal (internal, innermost) muscles are among them. During inspiration and expiration, these muscles work together to raise or lower the ribs as necessary. The costal cartilage’s sternal end is then moved in relation to the sternal costal notch as a result.

The deep (intrinsic) and superficial (extrinsic) muscles of the back are the second set of muscles that link to the ribs and move the sternochondral joints. Notable mentions include the iliocostalis, longissimus, levatores costarum, and serratus anterior and posterior muscles. They move the ribs during different trunk motions (extension, flexion, lateral flexion, and rotation), although their significance is secondary to that of the breathing muscles. Thus, at the sternochondral joints, the sternal ends of the costal cartilages are likewise shifted.

Clinical significance

Ankylosis spondylitis causes stiffness in the Sternocostal Joints caused by ossification. This leads to Sternocostal Joints pain during deep breathing and shallow breathing.

FAQs

The sternocostal joints: what are they?

The synovial plane joints connecting the sternum and the costal cartilages of the true ribs are called sternocostal joints, sternochondral joints, or costosternal articulations.The lone exception is the first rib, which has a synchondrosis joint because the sternum and cartilage are joined directly.

The second seventh sternocostal joints are which?

The synovial joint is the type seen in the second to seventh sternocostal joints. Each contains a fibrous capsule that is reinforced by a radiating sternocostal ligament on both the anterior and posterior sides. The ligament travels to the sternum from the costal cartilage.

What is the physiopedia for the sternocostal joint?

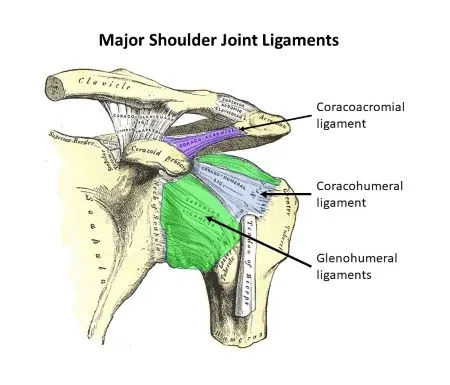

The articulation between the manubrium of the sternum with the medial side of the clavicle forms the Sternoclavicular Joint (SC joint). As the least restricted joint in the human body, the SC joint is the only real articulation that joins the upper limb to the axial skeleton.

What is the surface of the sternocostal region?

The heart’s sternocostal surface is oriented slightly to the left, superiorly, and anteriorly.The left, right, superior, and inferior boundaries of the heart make up this structure. In the anterior surface, the right ventricle occupies two thirds.

For what kind of joint might the first sternocostal joint be categorized?

A joint cavity lateral to the first sternocostal joint was observed radiographically in 10 specimens and represented a typical variation, but the first sternocostal joint could always be categorized as either a synchondrosis or a synostosis.

What is the sternocostal muscle used for?

The muscle’s sternocostal region has the ability to stretch the humerus back to its natural position and produce antagonistic action. The pectoralis major muscle, when its humeral connection is fixed, pulls the trunk upward or forward in conjunction with the latissimus dorsi muscle.

What is the triangle of sternocostal muscles?

Small defects in the posterior side of the anterior thoracic wall between the diaphragm’s sternal and costal attachments are called the foramina of Morgagni, or sternocostal triangles.Through these foramina, the internal thoracic vessels descend to form the superior epigastric vessels.

What is the sternocostal region of the chest?

Among the pectoralis major muscles, the sternocostal head is the greatest portion.In addition to working alone to extend the arm at the shoulder, it adducts the arm in conjunction with the clavicular head.The term “sternocostal” describes how this head originates on the ribs and sternum, or costal area.

What function does the sternocostal joint serve?

The rib and the sternum cannot move much because of the first sternocostal joint, a major cartilaginous joint.The articular surfaces of the costal cartilages and the sternum can glide together, which is necessary for breathing, thanks to the other six synovial joints.

What kind of joint is the initial sternocostal joint?

The first rib is joined to the sternum’s manubrium by hyaline cartilage at the first sternocostal joint, a synchondrosis-type cartilaginous joint. This results in a joint that is immovable (synarthrosis).

What does the term “sternocostal” mean?

belonging to, involving, or existing between the ribs and the sternum.

Does the sternocostal joint glide?

The thoracic region contains two sets of gliding joints: the sternocostal joints, which are between the ribs and the sternum (breast bone), and the vertebrocostal joints, which are between the vertebrae and the ribs. These joints allow the ribs to move slightly up and down, changing the volume of the thoracic cavity.

What is injury to the sternocostal joint?

The most common injury to the SC joint is a moderate sprain—a condition in which the surrounding ligaments are stretched—but it can also result in a fracture of the clavicle, or collarbone.A severe impact to the shoulder may occasionally result in an injury when the joint totally dislocates from its natural position.

References

- Sternocostal joints. (2023, October 30). Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/sternocostal-joints

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024, October 2). Sternocostal joints. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sternocostal_joints