Physical Examination Test for Elbow Joint

Overview

Elbow problems can severely affect a person’s physical health and financial stability. These conditions can limit mobility, making everyday tasks challenging, and lead to substantial medical expenses. Addressing elbow disorders is crucial for maintaining overall wellness and avoiding potential long-term consequences.

Elbow pain can originate in many different places, including bones, tendons, ligaments, bursae, and nerves. As a result, rehabilitation specialists need to be well-versed in both subjective and objective elbow assessment techniques and elbow anatomy.

What is an Elbow Joint?

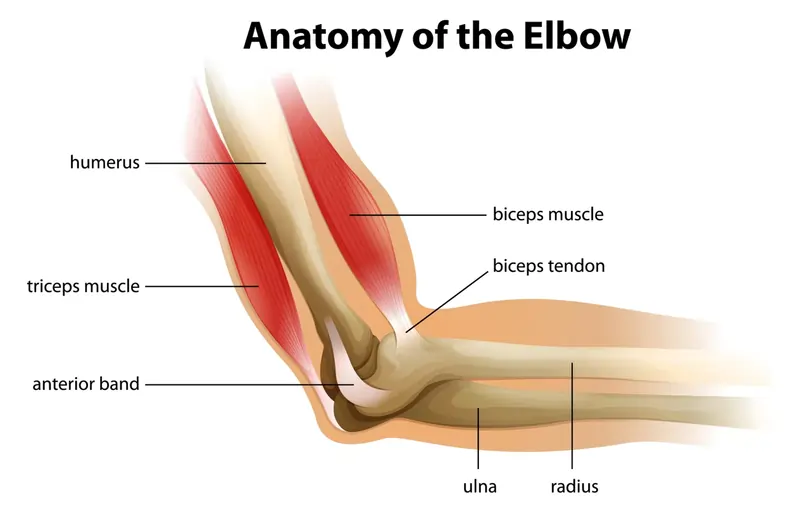

The elbow joint, which is composed of the radius and ulna bones, is the hinge joint that joins your upper arm (humerus) to your lower arm (forearm). It helps rotate your forearm and permits your arm to bend and straighten.

- Bones: The arm has two bones in the forearm – the ulna and the radius. Three bones make up the elbow joint: the humerus, or upper arm bone, and two other bones that cooperate to form this vital anatomical link.

- Cartilage: The flexible, lubricated cartilage that coats the bone ends within the elbow joint helps to minimize friction and safeguard these structures.

- Ligaments: The strong tissue bands that connect the elbow joint’s bones are called ligaments. The lateral collateral ligament is situated outside. The three main ligaments that surround the elbow joint are the elbow, the annular ligament, and the medial collateral ligament, which encloses the radius head and is housed inside the elbow ligament.

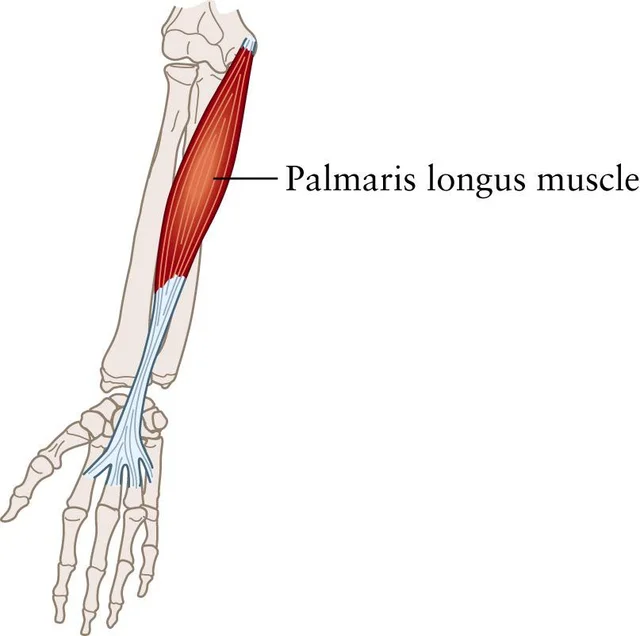

- Muscles: A number of muscles support and facilitate arm movement around the elbow joint. Your elbow can be bent by using your biceps muscle, and it can be straightened by using your triceps muscle.

- Tendons: Muscles and bones are connected by sturdy, cord-like structures known as tendons. These tough, fibrous tissues play a crucial role in transmitting the force generated by muscles to the bones, enabling movement and stability in the body.

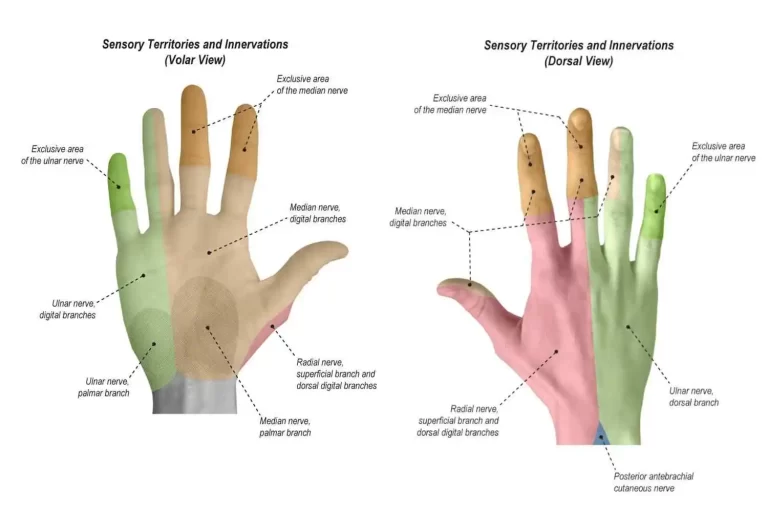

- Nerves: The elbow joint’s neural tissue gives the hand and arm feeling. Two significant nerves that cross the elbow joint are the median and ulnar nerves.

The elbow joint (synovial joint) is surrounded by a sac that have synovial fluid and allows for smooth movement.

Subjective History

- precise location of the discomfort

- Timeline: When are the symptoms that patients have reported being the worst?

- Mechanism of the injury: The mechanism of the injury serves as a guide for the diagnosis in cases of traumatic incidents. Certain symptoms can be very helpful in making a diagnosis of traumatic injuries. For instance, ulnar neuropathy may be indicated if the patient reported tingling or numbness in the fifth finger.

- Is there tingling or numbness present

- Drugs

- Past Medical History

- Imaging or diagnostic testing

Region-Specific Historical Question

The examination will be guided in part by these questions. As an illustration:

- Are your symptoms worsened or improved by any movements of your neck or shoulder?

- Has your elbow ever felt unstable?

- Does engaging in gripping activities alter the pain?

- Have you ever had tingling or numbness in your hands?

- When the injury occurred, did the elbow exhibit hyperextension?

- Do you associate the symptoms with throwing?

Environmental and Personal Factors

Environmental and individual factors ought to be taken into consideration during the first assessment.

Following an elbow injury, these problems may have an impact on recovery and function return.

Patients with other conditions may impact elbow injury recovery and function such as:

- Diabetes

- Suppression of immunity

- Contamination

- Multiple injuries at different sites

- Use of tobacco

- Abnormal alcohol consumption

Observation

Do not forget to look at the neck, elbow, wrist, and hand. Take note of both sides so that you can compare them. Crucial details at the elbow

- Notice how the extension’s carrying angle is calculated. Although carrying angle averages vary amongst studies, they typically fall within the range of 5 to 16 degrees for women and 5 to 14 degrees for men.

- Check for any scars, swelling, soft tissue alterations, or asymmetries.

Palpation

The elbow’s primary palpation points are listed:

Medial elbow

- Medial supracondylar line

- Medial epicondyle

- Ulnar nerve groove

- Ulnar nerve

- Common flexor tendon and pronator teres

Lateral elbow

- Common extensor tendon

- Lateral supracondylar ridge

- Lateral epicondyle

- Radial head

Muscles

- Biceps

- Brachialis

- Brachioradialis

- Common flexor tendon

- Common extensor tendon

- Triceps

Range of Motion

Evaluating the range of motion, both active and passive, including under excessive pressure, is crucial.

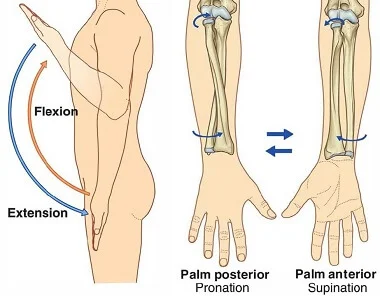

| Movement | Range of motion | Typical End Feel |

| Flexion | 0-145 degrees (active) 0-160 degrees (passive) | Soft |

| Extension | 0-15 degrees (hyperextension) values are given in the literature range between -6 and 11 degrees | Hard |

| Pronation | 80 degrees | Firm |

| Supination | 80 degrees values are given in the literature range from 80-104 degrees | Firm |

Assessment for Common Elbow Pathologies

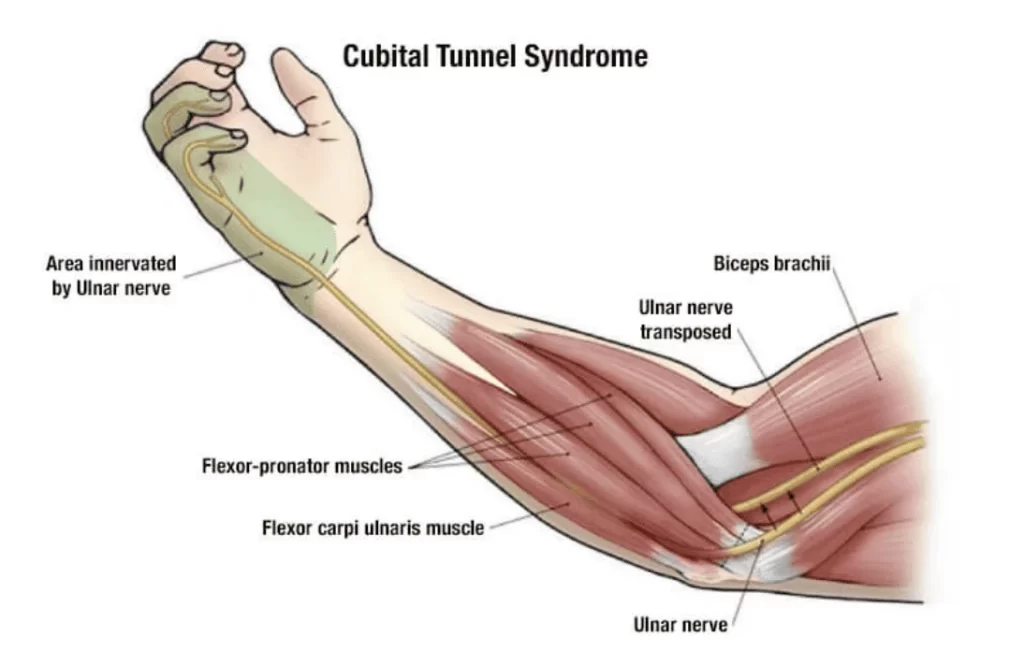

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Compression of the ulnar nerve, which runs along the inner side of your elbow, can result in Cubital tunnel syndrome. This nerve is essential for giving your pinky and ring fingers a feeling. It also sends signals to the hand muscles that enable you to pinch and grip objects. Affected people make up about 5.9% of the total population, making it the second most common mononeuropathy after carpal tunnel syndrome.

- Tingling and numbness in the area of the ulnar nerve distal to the elbow

- Complaints about positions

- Repetitive elbow flexion tasks or injuries to the elbow region

- Valgus stress

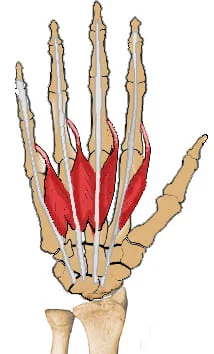

Observation: Search for atrophy in the ulnar nerve-supplied muscles (flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor digitorum profundus, lumbricals four and five, adductor pollicis, hypothenar muscles, dorsal and palmar interossei).

Palpation: Using your fingers, feel for any soreness at the ulnar groove.

Adaptability, whether at rest or in motion: To recognize possible signs of complete bending, Observe for the reappearance of issues during the gentle, unassisted range of motion.

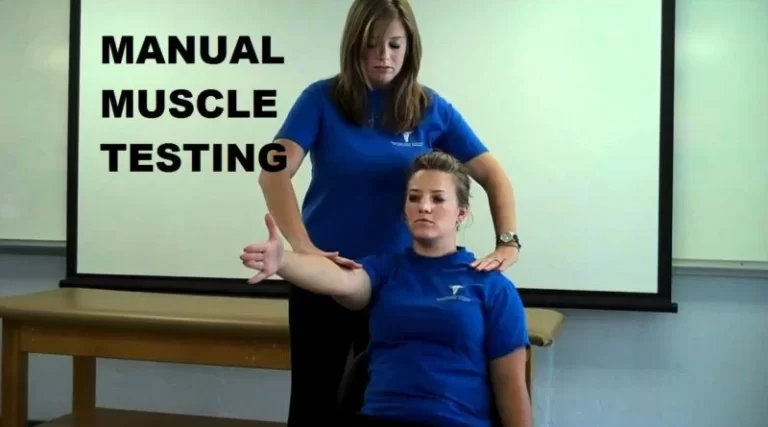

Manual muscle testing: Should you find any weakness in your muscles, it’s likely due to ulnar nerve supply.

Testing for accessory movement: should fall within acceptable bounds.

Special tests

- Pressure provocation test:

- Put pressure on the area close to the cubital tunnel and hold it there for no more than 60 seconds. If the patient starts to have symptoms along the ulnar nerve distribution, stop applying pressure earlier. The person’s arm should be positioned with the elbow bent slightly, forming a 20-degree angle.

- Positive test result: the patient’s symptoms are distributed along the ulnar nerve.

- Negative test: After compression is kept up for 60 seconds, the patient shows no symptoms.

2. Elbow flexion test:

- Flex the patient’s elbow and apply excessive pressure or the maximum amount of passive flexion possible.

- Hold this position for no more than 60 seconds; if the patient experiences any discomfort along the ulnar nerve distribution, stop the treatment sooner.

- Positive test results in symptom replication.

- Negative test: no symptoms were replicated in 60 seconds.

3. Combined pressure and flexion test:

and flexion test

- Combining the two tests mentioned above while the elbow is in a 20-degree flexion, apply pressure to the ulnar nerve directly in front of the cubital tunnel.

- Keep applying pressure while extending your elbows.

- Positive test results in symptom replication.

- Negative test: after 60 seconds, no symptoms were reproduced.

4. Tinel’s sign:

- The examiner lightly taps the ulnar nerve four to six times, proximal to the cubital tunnel, using their fingers or a reflex hammer – A test result that is positive causes the ulnar nerve’s distribution to recur with the same symptoms.

- Negative test: no symptoms were reproduced.

Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) Tear

A sprain of the medial collateral ligament happens when the elbow experiences a valgus force greater than the medial collateral ligament’s tensile characteristics (MCL). Throwing athletes are more likely to sustain this injury.

History:

- Injuries where valgus stress or recurring stress (throwing, for example)

- Patients with ongoing wounds might report hearing a “pop.”

- Patients with chronic injuries might have observed a decline in their throwing accuracy or velocity.

- Discomfort in the medial elbow

- Expanding

- Bruises

- In patients who experience a complete rupture, instability will be reported.

Observation: Look for any indications of swelling or bruises on the medial elbow.

Palpating: Check the inner side of the elbow for any signs of tenderness.

Motion range, both in an active and passive manner: Most likely within standard parameters.

Accessory movements: A lack of use of this test notwithstanding, it is likely to cause excessive medial glide of the ulnar, with or without pain; no discernible changes occur upon distraction.

Special Tests

- Moving valgus stress test:

- Although this test is “currently accepted as the gold-standard clinical test,” patient tolerance must be taken into account.

- The patient should have their elbow fully extended and their shoulder in a 90-degree abduction.

- Position of Patient: Externally rotate the shoulder, extend the elbow, and apply valgus stress to the shoulder.

- Positive tests revealed that one side was more mobile or in pain than the other.

2. Valgus stress test:

- At 30, 60, 70, and 90 degrees of elbow flexion, apply valgus stress along the lateral elbow towards the midline.

Lateral Elbow Tendinopathy

With a 1-3% population prevalence, lateral elbow tendinopathy—also referred to as lateral epicondylalgia, lateral epicondylitis, and tennis elbow is one of the most common causes of elbow pain and dysfunction. The majority of those who have it are between 40 and 50 years old.

History:

- Unease when gripping objects, such as a doorknob, a coffee cup, or a handshake.

Observation:

- It’s possible that patients won’t shake hands.

- They might have on a brace.

Palpation: Palpation reveals soreness in the common extensor tendon and muscles as well as along the lateral epicondyle.

Range of motion, both passive and active:

- In addition to the discomfort, there is also movement in the elbow and stretching of the wrist, both done actively and passively.

- Discomfort when actively extending the wrist

Resisted range of motion:

- Discomfort upon resisting wrist extension

- Pain when extending the middle finger is resisted

- Accessories: usually kept within reasonable bounds.

Special Tests

- Muscle tests:

- Palpable pain

- Pain when the common extensors are stretched

- Discomfort upon resisting wrist extension

2. Grip power using a dynamometer (if one is available):

- Contrast the sides

- Probably restricted and painful on the injured side

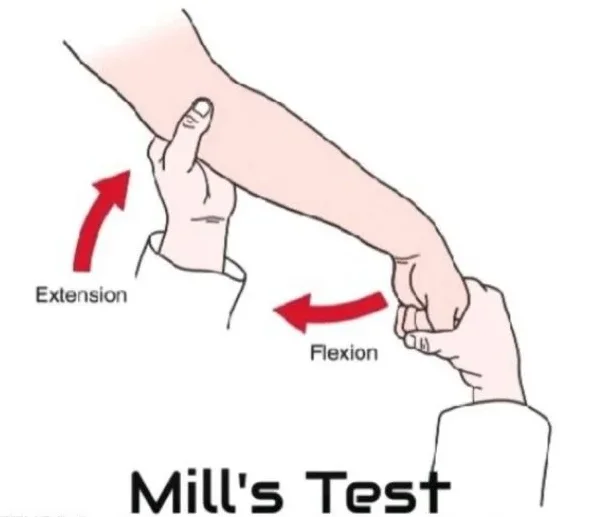

3. Mill’s test:

- The patient’s arm is positioned with its elbow bent.

- After palpating the patient’s lateral epicondyle, the examiner passively extends the elbow, flexes the wrist, and pronates the patient’s forearm (as demonstrated in the optional video below).

- Torment over the sidelong epicondyle of the humerus is shown by a positive test.

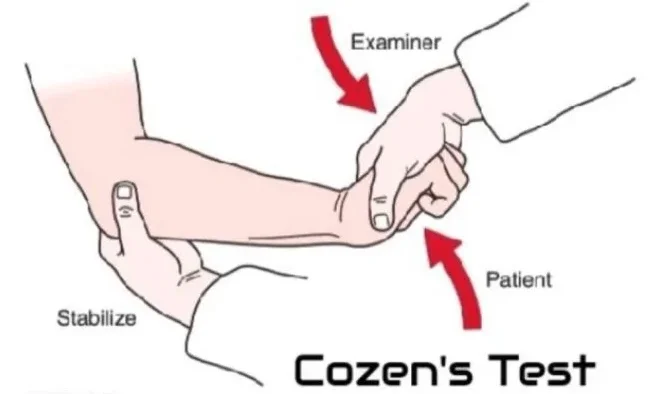

4. Cozen’s test:

- The thumb of the examiner is placed on the patient’s lateral epicondyle.

- The patient is positioned with their elbow bent and turned outward, and their wrist extended and twisted to one side.

- Hesitance to twist the analyst’s wrist or influence in one heading.

- Positive test results include the recurrence of similar symptoms and an abrupt, excruciating pain at the lateral epicondyle of the humerus.

Medial Elbow Tendinopathy

Elbow pain along the inner side of the joint is a common condition known as elbow tendinopathy. This ailment is marked by discomfort in the area around the middle part of the elbow. Another name for it is “golfer’s elbow”. It arises from overuse or repeated straining of the tendons that bend your fingers and wrists.

History:

- Wrist flexion and supination combined with discomfort in the medial elbow

- Discomfort when doing activities such as hammering, screwdriver use, and any squeezing motion (like gripping a baseball bat or golf club).

Observation: Resistance among patients to shake hands has been noted.

Palpation: The muscles, normal flexor ligament, and average epicondyle are delicate.

Range of motion, both active and passive: Discomfort when extending the elbow and the wrist.

Resisted range of motion: Discomfort when pronating the forearm and flexing the wrist.

Biceps Tendon Rupture

- Biceps tendon rupture proximal: This happens at the shoulder, where the tendon joins the upper portion of the shoulder socket.

- A distal rupture of the biceps tendon occurs at the elbow, where it joins the radius bone, one of the two forearm bones.

History: the patient describes a particular occurrence in which their ability to bend their elbows immediately decreased.

Observation: As the biceps muscle retracts, you can see the defect after a few days.

Palpation:

- Possibly able to feel a flaw

- Possibly experience biceps tenderness

There are two ranges of motion available for elbow flexion: a full passive range and a restricted active range.

Resisted range of motion: Resisted elbow flexion accompanied by weakness.

Special Tests

- Biceps squeeze test:

- The patient is sat with their elbow bent between 60 and 80 degrees, and their forearm lying on their lap with a little pronation.

- With both hands, the examiner applies firm pressure to the patient’s biceps, moving the first along the muscle belly and the second at the distal myotendinous junction.

- Positive test result: when the biceps are squeezed, there is no forearm supination.

2. Test of passive forearm pronation:

- While sitting, the patient keeps their elbows bent at a 90-degree angle.

- Examiner: The patient’s forearm is initially supinated, then gradually becomes pronated.

- The test was positive when there was no longer any palpable or noticeable movement in the bicep muscle’s belly.

3. Biceps crease interval:

- The patient bent their elbows at a 90-degree angle.

- The examiner’s Hand Position applies pressure to the antecubital fossa with a fingertip.

- Examiners measure the distance from the antecubital crease to the distal muscle belly by passively extending the patient’s elbow and supinating their forearm.

- A positive test result is indicated by a distance greater than 6 cm.

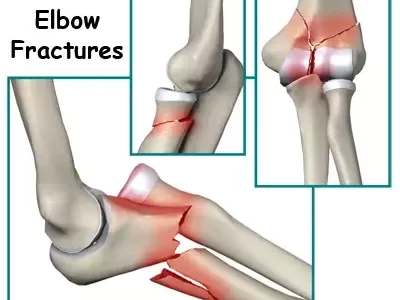

Elbow Fracture

Elbow fractures account for 7% of all fractures. Children are more likely to sustain extra-articular fractures. Adults over 50 have a higher risk of developing articular fractures. In younger adults, elbow fractures are typically the result of high-energy injuries (e.g., motor vehicle crashes, sports, falls from a height).

Special Tests

Radiography needs can be evaluated using the test results.

- Test of four-way range of motion:

- One arm resting by the patient’s sides and their elbow extended are shown in the seated position.

- The following is requested of the patient:

- Extend to the point of full lock

- Elbow flexion to a 90-degree angle

- Pronate to the extent of their range of motion while flexed.

- Reduced range of motion in any of the four maneuvers indicates a positive test.

- The negative likelihood is 0.02 and the positive likelihood is 2.47 according to the probability ratios.

2. Elbow extension test:

- With their arms folded, the patient is sitting.

- It is requested of the patient to consciously flex their shoulders to a ninety-degree angle.

- Next, the patient stretches their elbow.

- If the test results are positive, the affected elbow’s range of motion will be reduced.

- The probability ratio is 1.88 for the positive case and 0.06 for the negative case.

Self-Report Outcome Measures

- DASH (Quick Dash)

- Patient-Specific Functional Scale

- ASES and PREE: Using two comparable scales, patients can self-report their pain and disability associated with elbow pathology: the American Shoulder and Elbow Society evaluation (ASES) and the Patient-rated elbow evaluation (PREE). The two scales have very little conceptual variance, and their correlation is typically higher than 0.90.

- P4:P4 is a four-item scale for pain intensity. On the P4, patients are asked to rate their level of pain during the morning, afternoon, evening, and during the previous two days while they are active.

Special Questions

Red Flags

- Inflammation/Infection

- Cancer

- Test for Fracture/Dislocation of the Positive Elbow Extension

- Proliferative Arthritides

- Unusual Vitals

- Unusual Neurological and Vascular Exam

- Heterotopic Ossification: A Matter to Be Considered After Surgery

- Inappropriate recovery from post-operative care

Yellow Flags

- Psychosocial elements

- Inert coping

- Avoidance of Fear Beliefs

Investigations

Even though a physical examination is a good place to start, imaging tests might be required to confirm a diagnosis or provide a better view of the elbow joint’s internal structures. The following imaging tests are frequently used to investigate elbows:

- Radiography: Quick and effective way to view bones. Diagnose arthritis, bone spurs, fractures, and dislocations.

- MRIs, or magnetic resonance imaging, are a type of imaging that creates finely detailed pictures of blood vessels, soft tissues like tendons and ligaments, and bones using magnetic fields and radio waves. Ligament tears, tendonitis, bursitis, and bone marrow edoema can all be diagnosed with MRIs.

It’s crucial to remember that your doctor’s specific test orders will be based on your medical history and specific symptoms.

Neurologic Assessment

- Reflexes: C5-C7

- Myotomes: C5-T1

- Dermatomes: C5-T1

Summary:

A standard step in the diagnosis of elbow pain or injuries is a physical examination of the elbow joint. Usually, there are multiple steps involved:

- Examining the elbow from all angles, the physician will visually inspect it for any signs of bruising, swelling, redness, or deformity.

- Palpation: To feel for soreness, warmth, or instability, the physician will palpate the elbow joint and the tissues around it.

- Range of motion: The physician will evaluate the flexion (bending), supination (turning the palm up), extension (straightening), and pronation (turning the elbow).

- Stress tests: To evaluate the stability of the elbow ligaments, the physician may carry out stress tests. While some discomfort may be felt during these tests.

- Neurologic testing: To rule out nerve damage, the physician may test the hand’s and arm’s sensations and reflexes.

The following extra tests could be carried out based on the suspected condition:

- Tinel sign: This test determines whether or not nerve irritation is present. To determine whether it causes tingling or pain, the doctor will tap the nerve with the finger.

- Examining the elbow’s outer lateral collateral ligament (LCL) for stability is known as the Varus Stress Exam. To check for laxity or pain, the doctor will apply a valgus stress, which involves pushing the elbow inward.

It’s critical to visit a physician if you’re having elbow pain to receive an accurate diagnosis and treatment recommendations. Your long-term prognosis can be improved and additional injuries can be avoided with early diagnosis and treatment.

FAQs

How is an elbow joint examined?

1. Check the elbow’s appearance from the front, back, sides, and middle.

2. Check for nodules, swellings, scars, and changes in the skin.

3. Examine the other elbow to check for any asymmetry.

4. Examine the elbow’s carrying angle.

How is cubital tunnel syndrome recognized?

The most prevalent symptoms are discomfort, tingling, and numbness in the little finger, ring finger, and hand, particularly when the elbow is bent. Rest and anti-inflammatory medications can be used to treat cubital tunnel syndrome. Activity can also be beneficial. There are situations where surgery is necessary.

How can one determine whether they have an elbow fracture?

1. Check for any additional tender spots by feeling the area surrounding the elbow.

2. Look for cuts from broken bones on your skin.

3. Verify that your hand and fingers are receiving enough blood flow by feeling your pulse at the wrist.

4. Verify your range of motion.

For whom is epicondylitis a risk?

People who play badminton, squash, tennis, or any other activity requiring repetitive wrist extension, radial deviation, and/or forearm supination are prone to it. This exercise will go over the most frequent causes of lateral epicondylitis as well as the most effective course of treatment based on available research.