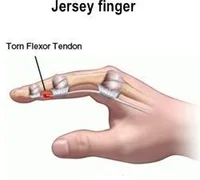

Definition

The Jersey finger, often known as the “rugby finger,” is an avulsion of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon (FDP) from the distal phalanx (zone I), where it is inserted. The most often impacted is the ring finger. In the gripping posture, the ring finger protrudes the farthest, making it more susceptible to FDP avulsion, which results in an inability to flex at the DIPJ.

A rupture of the flexor tendon, which is responsible for bending the fingertip downward, is referred to as a “jersey finger.” Football players who have grasped the jersey of an free to play who is Its name comes from its attempts to escape. The finger unexpectedly straightens as the player tries to release themselves while still attempting to flex and hold. As a result, the tendon is pulled in two different directions, creating a tug of war. As a result, the tendon may detach from the bone where it inserts at the fingertip. Occasionally, a fragment of the bone is also ripped off. Although this is a classic illustration, jersey finger can also result from other sports and hobbies (like rock climbing).

The forearm is where the majority of the tendons that move your fingers begin. The muscle that bends the fingertip downward is called the flexor digitorum profundus. Consequently, FDP avulsion is the medical word for a “jersey finger.” Type I, Type II, and Type III are the three varieties. The most severe is kind I, in which the tendon completely retracts into the palm. The most advantageous type is Type III.

The tendon retracts very little or not at all. Every joint has a blood supply to the flexor tendon. Therefore, more of the blood supply is interrupted when the tendon is retracted toward the base of the finger, away from the tip. The speed of your recovery and the effectiveness of your treatment may be impacted by a loss of blood flow.

Epidemiology

Of all acute injuries to the upper extremities, 38% are to the fingers. According to a recent study, the frequency of hand tendon injuries is 33.2 per 100,000 person-years. The flexor tendon zone accounts for just 4% of these injuries.

The most frequent closed flexor tendon injury is a Jersey finger, which can occur in any digit. In 75% of instances, the ring finger is the digit most frequently affected. For the great majority of people, the ring fingertip is the most noticeable digit while gripping.

Additionally, the ring finger is particularly susceptible to hyperextension injuries because it is lumbrical muscle-bound on both sides. According to some reports, the ring finger’s FDP tendon requires a far lower force to failure than other digits.

Pathophysiology

Failure is caused by excessive extension of the DIP joint during maximal FDP tendon belly contract (clenched fist). The distal tendon insertion at the base of the phalanx is injured since it is its weakest place.

Types

Partial Rupture

The injury may be less serious if only a portion of the tendon is ripped. Although it will be uncomfortable and restricted, you may still be able to move your finger to some degree. Your doctor may determine that a finger splint, rest, ice, and elevation are appropriate treatments if the damage only involves a partial rupture of the tendon.

Complete Tendon Rupture or Bone Chip Rupture

The damage is more severe and the finger won’t heal on its own if the tendon is torn or if there is a chipped bone attached. To fix soft-tissue damage and regain your finger’s range of motion, surgery will be necessary.

Mechanism of Injury

- The Tackle Attempt: During a tackle or block, a player may reach out and grasp their jersey in an attempt to bring the pace down or gain control of the opponent. This motion is frequently executed swiftly and forcefully.

- Finger Entanglement: The player’s finger may become twisted in the fabric as their hand closes around the jersey. The force created by abruptly pulling the jersey might cause the finger to extend uncomfortably.

- Tendon Overstretch: The finger’s flexor tendon, which runs along it and gives its bending ability, can be tugged or overstretched beyond its typical range of motion. This overstretching might cause the tendon to tear or rupture.

- Impact Force: The severity of the damage may be influenced by the impact force. For example, the force may exacerbate the rip if the player’s A finger gets jammed in the jersey and is struck by the opponent’s body or another object.

Stages and classification of injury

The degree of tendon retraction and the existence or absence of a fracture serve as the basis for the classification system of jersey finger injuries.

- Type I: The FDP tendon retracts to the palm at the origin of the lumbrical.

- Type II: Involves the FDP tendon retracting to the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint, which is the A3 pulley.

- Type III: Large bone fragment avulsion. Both the fracture fragment and the FDP tendon withdraw to the A4 pulley because the bone fragment prevents further retraction.

- Type IV: A big bone fragment is avulsed, and the FDP tendon separates from the bone fragment as a result. The FDP retracts into the palm because the avulsed FDP is not joined to the bone fragment.

- Type V: A substantial bone fragment is avulsed, and the distal phalanx sustains another large fracture.

Causes

Pull-away devices expose the distal phalanx to significant stresses. Young athletes frequently develop flexor digitorium distal avulsion, particularly in contact sports. Usually, a flexed digit’s forceful extension causes the damage mechanism.

In American football or rugby, a typical example is grasping an opponent’s jersey to make a tackle, which causes the flexor digitorium profundus tendon to be forced to extend during maximal contraction of the muscle belly.

Signs and Symptoms

Although the wounded finger may be able to bend at the other joints, a jersey finger prevents the injured finger from bending at the fingertip. Depending on how the damage happened and how much time has gone by after it happened, the fingertip may be painful and swollen. When an injury occurs, people frequently describe hearing or experiencing a “popping” sound. Any finger may be impacted, although the ring finger is most frequently. A Type 1 rupture may be indicated if there is significant pain in the palm immediately before the base of the finger.

- Numbness in your fingertip

- At the site of injury, there was a pop sound.

- Pain: It’s normal to experience a sharp or throbbing pain at the fingertip or near the joint. Usually, this sensation gets worse as you try to move the finger.

- Swelling: In comparison to the other fingers, the affected one may swell up and appear puffy.

- Inability to Bend: The inability to bend the fingertip is one of the most obvious signs. The tip of your finger is still stiff, but the rest of it may bend.

- Tenderness: The finger may probably feel sensitive to the touch, particularly in the vicinity of the damaged tendon joint. Tenderness on the hand’s palm side of the hand.

- Bruising: Although it’s not always there, some bruising may develop around the location of the injury.

- Deformity: In extreme situations, you may observe an obvious deformity or an unusual finger posture.

Risk Factors

The following variables may make getting a jersey finger more likely:

- High Contact Sports: Players who regularly grasp and tug on each other’s clothing in sports like rugby and football are more likely to sustain this injury.

- Aggressive Play: Players who are extremely aggressive or employ strong techniques are more prone to such injuries.

- Inappropriate Technique: Inappropriate attacking or gripping techniques can occasionally cause extra finger strain, which might result in a jersey finger.

Diagnosis

The history and physical examination are frequently the only factors used to make the diagnosis. Many times, patients and even physicians who don’t specialize in hand surgery may miss a jersey finger. They won’t notice that the fingertip is not moving since they will only notice that the first two finger joints are bending. In other instances, the fingertip may be seen to be immobile, but people often assume that this is because of pain or swelling. Your hand surgeon may attempt to isolate your movement during the diagnostic by keeping your knuckle joint straight to avoid bending and testing your fingertip’s range of motion. You most certainly ruptured the tendon if it does not move.

When a patient is unable to flex their DIP joint, a clinical diagnosis is made. Ultrasound can be used to confirm the diagnosis and identify the proximal stump of the avulsed tendon.

Athletes who experience finger pain should have a physical examination, X-rays, and ultrasound to rule out fractures and link these injuries to damage sustained during sports. Although it is infrequently used, MRI can assist in a thorough assessment of the injury and may be useful in determining the degree of tendon retraction. To check for FDP avulsion, do the following test.

Radiographic features

Plain radiograph

Radiographs can often be normal. When a bone avulsion occurs, there may be a triangular avulsion fragment at the volar aspect of the distal phalanx base, along with visible soft tissue swelling.

MRI

Avulsion fragment at the volar base of the distal phalanx disrupting the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP). The placement of tendon ends can also be seen using MRI, which influences the patient’s surgical classification and care.

A physical examination will also reveal that, in comparison to the other digits, the wounded finger remains extended. Additionally, the retracted tendon is palpable proximally to the avulsion; the DIP joint does not flex, and gripping and flexing against resistance hurts a lot.

Bony pieces may be visible in the X-ray’s lateral and anterior views. To assess tendon retraction and direct additional treatment, ultrasound is typically essential. Although it is rarely done, MRI can be utilized to more precisely measure the increased tendon-bone distance.

Differential Diagnosis

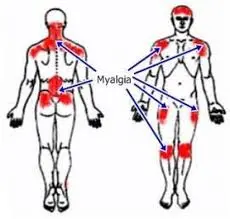

- Muscle sprain

- Phalanx fracture

Treatment

Your injury will determine the course of treatment. Your course of treatment can change if you also have a fractured bone in addition to the jersey finger. Surgery is usually beneficial for most of these injuries because it allows the fingertip to bend again, repairs the bone fracture if needed, and reattaches the damaged tendon. This is especially true for athletes and young, energetic patients.

Due to underlying medical issues or an inability or unwillingness to adhere to post-surgical instructions, such as taking it easy and/or getting hand rehabilitation, some patients may choose not to have surgery. Without surgery, the inability to flex the fingertip will probably be irreversible. Discuss the best course of action with your hand surgeon.

Medical Management

- Surgery might not be required if the flexor tendon was only partially ripped, which is uncommon.

- To assist in stabilizing the finger and give the injured tendon time to heal, the patient can be advised to wear a splint.

- After one to three weeks of immobilization and rest, physical therapy will be used in conjunction with the use of a splint to assist restore strength and movement to the injured finger.

- Most often, injuries to the jersey finger are treated with surgery. Restoring blood flow and function requires early intervention. Blood veins inside the mastoidal (long and short vincula) provide nutrition for flexor tendons. There are few reports of conservative care for surgical patients at high risk.

Surgical Management

- The mainstay of treatment for Jersey’s finger is surgery; conservative measures are only taken when complications prevent surgery. Restoring the damaged digit’s pain-free active range of motion requires surgery.

- The best course of treatment is surgery, which should be done as soon as possible—typically within three weeks after the accident. Staged tendon reconstructions, tenodesis, and DIP joint arthrodesis are surgical salvage techniques for late presentation.

Avulsion injuries of the FDP are treated with a variety of surgical methods, such as the following:

- The Bunnell pull-out suture technique

- Suture anchor repair

- Integration of the volar plate to repair the tendon.

Clinical outcome studies are still being developed for the latter approach, which is the most current to be described.

- The most often utilized method has historically been the pull-out suture procedure.

- Effective postoperative rehabilitation should allow patients to resume routine activities and sports after 8–12 weeks.

Acute: 3 weeks following the injury.

- Direct tendon repair or tendon reinsertion (mini-suture anchor) are options if there is no fracture.

- Fracture fragment: needs open reduction and internal fixation (wires, mini-screws). These days, bone avulsions are also treated with suture anchors.

- For acute injuries, there are numerous documented, effective treatment methods. It appears that none of these are noticeably better than the rest.

Chronic: lasting longer than three months after an injury.

- Tendon grafting in two stages (assuming the entire range of motion is available).

- DIP joint arthrodesis (in the event of persistent stiffness). Every patient must have a thorough conversation about joint arthrodesis. For some patients, tendon reconstruction may be a viable alternative to distal interphalangeal joint motion, which is necessary for their careers and hobbies.

- Unfortunately, to obtain a successful long-term rehabilitation outcome, tendon repair necessitates a large time commitment from the patient.

Surgical Tips Include

- Final circumferential suture improves final repair strength.

- Incisions should be made in low-risk areas to retrieve the tendon.

- Accurate tendon orientation is crucial.

- Tendon handling should be minimal.

- Sheath closure is only done if it enhances tendon gliding; it is not required.

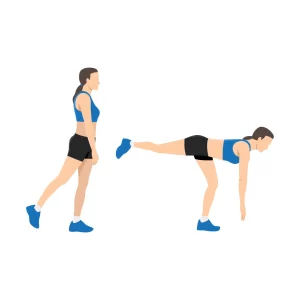

Physical therapy treatment

After surgery, athletes should anticipate missing 8–12 weeks of play. After surgery, athletes are evaluated according to their position during play and level of competition using a sport-specific hand rehabilitation plan that includes

Initial care for Partial Ruptures

Treatment for a partial flexor tendon rupture often consists of non-surgical techniques:

Finger Splint:

To facilitate healing, this keeps the finger in a steady position. Eight finger splints and various finger splints can be used to cure oval jersey fingers. A Jersey finger is a common injury in contact sports, such as ball sports. It stabilizes the finger, relieves pain and suffering, and lets the injured tendon heal itself.

- Rest: To avoid more harm, do not use the damaged finger.

- Elevation and ice are two techniques that assist in lessening pain and swelling.

- Dorsal Blocking Splint (DBS). To immobilize the finger and encourage healing in the proper posture, a dorsal-blocking splint is frequently utilized initially.

- Passive Range of motion (ROM) exercises in the early postoperative phase. The therapist uses light finger movements to preserve joint mobility, particularly in the initial post-operative period.

- Active or assisted ROM exercises. After being given permission, the patient will progressively advance to increasingly difficult activities by actively moving the finger through its range of motion.

Exercises that facilitate the tendon’s smooth movement within its sheath are known as tendon gliding exercises.

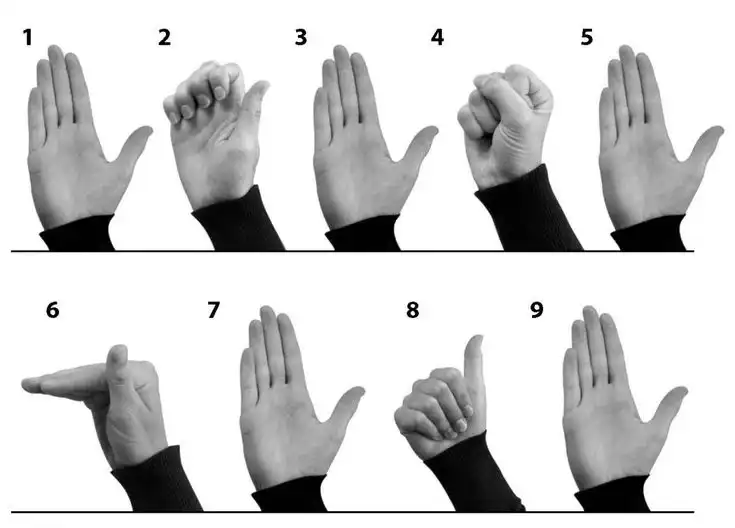

Tendon gliding exercises

Procedure:

- Hook the tips of your fingers toward your palm after starting with your fingers straight. Keep your wrist and knuckles straight. Return to your starting point.

- Beginning with your fingers straight, bend them at the knuckles to create a perfect angle while maintaining their straightness. Return to your starting point.

- To create a “flat fist” on your palm, begin with your fingers straight and gradually curl their tips inward. Return to your starting point.

- Start with your fingers straight, then roll them into a full fist by curling the tips down. Return to your starting point.

After hand surgery or an injury, tendon gliding exercises are crucial for preventing and minimizing tendon adhesions. When the body begins to mend, adhesions are created; scar tissue holds two surfaces together that aren’t supposed to be together.

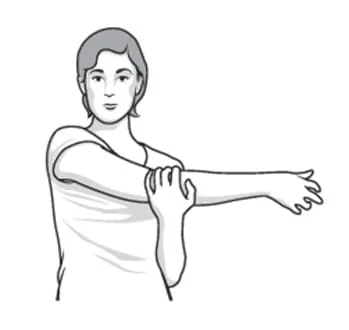

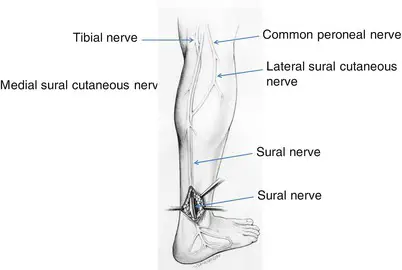

Nerve glide is a nerve-stretching exercise, sometimes referred to as nerve flossing or nerve stretching. It makes it easier for the body’s peripheral nerves to move smoothly and regularly. It releases the nerve from compression and permits the nerve to move freely with the joint.

The primary advantage of glides is that they are more effective at protecting surfaces than wheels or permanent bases because they take more force to move than wheels, making them ideal for furniture that won’t be moving about a lot. Additionally, they are simple to install, making it simple to swap out worn glides.

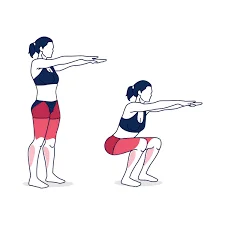

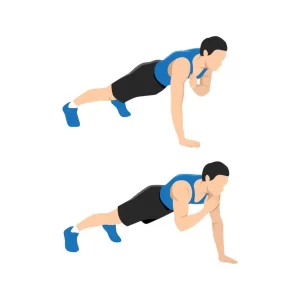

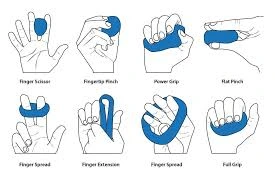

Strengthening/power grasping exercises.

Activities such as grip and pinching exercises progressively increase the strength of the finger muscles. The towel ring is an excellent workout to do at home to strengthen your grip if you have little equipment. To wring out the water, soak a small towel, grasp it at either, and twist it in opposite directions. Repeat multiple times with the directions inverted.

Hand Kinetics will determine the muscles involved, analyze the cause, and develop a training program that will accomplish two primary goals to increase grip strength:

- First: Safeguarding brittle joints

- Second: Promote the contraction of the muscles required to carry out particular tasks.

This usually include a graded schedule that includes daily activity and one or two days off. Initially, these are simple exercises designed to create a neural pathway for movement. Exercises that are later eccentric and concentric can be added.

We test your muscles with resistance bands, grip masters, and dumbbells, and we provide tips on how to employ everyday tasks to work out your hands at home.

For instance:

- To strengthen your wrist muscles, lift a bottle of water several times before drinking it.

- For 30 seconds, try holding two tin cans in the palm of your hand.

- Try wringing out a damp cloth with warm water.

Scar massage

Manual therapy is used to increase flexibility and break down scar tissue.

A “jersey finger” scar massage include using light to medium pressure and circular motions to gently massage the scar tissue left behind after surgery to repair the injured flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendon. Usually, a moisturizing cream is used to reduce adherence and increase flexibility in the affected finger. This should be done as prescribed by a healthcare provider after healing has occurred.

Massage technique:

- Apply a small amount of moisturizer or lotion to the scar area.

- Use your fingertips to gently massage in circular motions along the scar.

- You can also try gentle linear motions, moving in the direction of the scar.

- Gradually increase pressure as tolerated, but avoid excessive force.

- Frequency: Massage the scar several times a day, for a few minutes each session.

Benefits:

- Helps to soften and flatten the scar tissue.

- Enhances the area’s blood flow, which aids in healing.

- Can reduce pain and tightness associated with the scar.

For example,

Early Phase (0-6 weeks):

- Active Range of Motion (ROM): Gently bend and straighten the affected finger, keeping the middle and distal joints straight.

- Passive ROM: The therapist or caregiver performs the movements for the patient.

- Splinting: A dorsal blocking splint immobilizes the finger in a slightly bent position to protect the tendon.

Intermediate Phase (6-12 weeks):

- Active Resistance Exercises: Use rubber bands or light weights to resist the bending motion of the finger.

- Tendon Gliding Exercises: Massage and stretch the tendon to improve its mobility.

- Proprioceptive Exercises: Activities that challenge the patient’s sense of position and movement in the hand.

Advanced Phase (12 weeks and beyond):

- Strengthening Exercises: Progress to heavier weights or resistance bands to build finger strength.

- Functional Exercises: Incorporate activities of daily living, such as grasping objects or making a fist.

- Sports-Specific Drills: For athletes, specific drills are tailored to their sport to regain full function.

Home care

Ice

Three to five times a day, apply an ice pack to the affected finger for five to ten minutes at a time. To prevent ice burns, avoid putting the ice directly on the skin.

Elevation

When you are seated or lying down, place your hand on a pillow. Reducing edema and pressure on the damaged area can be achieved by elevating the hand.

Prognosis

- Excellent functional outcomes and accelerated treatment are the results of early diagnosis. Excellent patient-reported outcomes are associated with surgery performed within 10 days of the accident.

- After around eight to twelve weeks, patients may resume sports with both a full active functional range of motion and no pain.

- Loss of pinch strength and dexterity are two functional effects of decreased DIP joint mobility.

- Accurate reduction, high-quality repairs, and a suitable rehabilitation regimen are necessary for both functional and aesthetic outcomes after surgery. Maintaining finger function requires preventing the growth of scar contractures.

Complications

Quadriga is a concern if a tendon advances more than 1 cm. Quadriga is the inability to flex the digits next to the injured digit due to increased tension over the tendon that has been healed.

Adhesions, nail matrix damage, tendon repair rupture, infection, and skin necrosis are other surgical complications.

- Unstable DIP joint

- Development of secondary osteoarthritic changes

- DIP flexion contracture or quadrigia

Conclusion

- A tendon tear that causes the fingertip to bend is known as a jersey finger. Another name for it is rugby finger.

- The most frequent injury to the closed flexor tendon is this one. It is frequently caused by attempting to seize an opponent’s jersey during a fast-paced athletic event.

- Although surgery is the most common form of treatment, occupational therapy and splinting may also be used. Although it may take up to six months to restore a complete range of motion, the repaired tendon will often return to full strength after 12 weeks.

FAQs

What distinguishes jersey finger from mallet finger?

Even if treatment is postponed for up to three or four months, the majority of mallet finger injuries will recover with non-operative care over eight to twelve weeks. Acute jersey finger diagnosis necessitates surgery and typically results in 8–12 weeks of incapacity to participate in most contact sports.

What is the unique jersey finger test?

Most likely diagnosis: A rupture of the FDP tendon from the distal phalanx is known as a jersey finger. Special test: Ask the patient to flex at the DIP while holding their MCP and PIP at full extension. The patient will be able to flex at the DIP if the FDP is unbroken. To isolate the FDP function, the PIP must be held at full extension.

Can an injured jersey finger cure itself?

A full tendon rupture or a rupture with a bone chip attached are the most common types of jersey finger injuries that prevent the finger from healing on its own. To restore your finger’s flexibility and cure soft-tissue damage, surgery will be necessary.

How can a jersey finger be fixed?

Surgery is necessary in almost all cases of severe jersey finger, particularly when the tendon is severely damaged or ripped. The tendon is surgically reattached to the bone, and then the patient is immobilized and undergoes targeted rehabilitation.

What kind of surgery is used to treat jersey fingers?

In addition, injuries to the jersey finger must be identified and treated right away to prevent the affected finger from becoming permanently disabled. Unfortunately, many of these injuries have delayed expression. A pull-through approach with a dorsal flap over the nail is the basic surgical repair technique.

How long does it take to recuperate from surgery on the jersey finger?

You will have a splint to assist brace your hand when you wake up. You will be given physical therapy exercises to start performing at home after wearing the splint for a few weeks. Your finger’s range of motion will be entirely restored with the use of these workouts. A full recovery should occur in eight to twelve weeks.

What kind of jersey finger splint is best?

The orthosis shouldn’t make the skin red or irritated. Because they can be made with a heat gun, Oval-8 Finger Splints—which come in CLASSIC Beige and NEW Oval-8 CLEAR—are an excellent option. A “must have” for creating or custom-fitting thermoplastic splints is a heat gun.

How can my fingertips become better?

Give your finger joints some rest so they can recover. Raise the finger and apply ice. To lessen pain and swelling, take over-the-counter medications such as naproxen (Aleve) or ibuprofen (Motrin). Buddy tapes the wounded finger to the adjacent one if necessary.

What’s the term for a stuck finger?

A disorder known as trigger finger makes it difficult to move your thumb or fingers. They may become “frozen” in a flexed position. Your thumbs and fingers’ tendons are impacted. The term “trigger finger” refers to the position in which your fingers can become caught, giving the impression that you’re attempting to pull an invisible trigger.

Reference

- Jersey Finger: Symptoms and Treatment | The Hand Society. (n.d.). https://www.assh.org/handcare/condition/jersey-finger

- Saber, M., & Ho, A. (2013). Jersey finger. Radiopaedia.org. https://doi.org/10.53347/rid-23394

- Patient, R. M. (n.d.). Jersey Finger | Rehab my patient. https://www.rehabmypatient.com/hand-fingers-thumb/jersey-finger

- Stockton, T., & Stockton, T. (2024, September 6). Jersey finger: What is it? | The Jackson Clinics. The Jackson Clinics Physical Therapy. https://thejacksonclinics.com/jersey-finger-you-got-a-problem-with-that/