Hip Joint

Introduction

The hip joint is a ball-and-socket synovial joint that serves as the primary connection between the lower limb and the pelvis. It is one of the largest and most stable joints in the body, designed to bear weight and allow a wide range of motion for activities such as walking, running, and jumping.

This structure allows numerous motions, including flexion, extension, rotation, and abduction.

The joint’s natural stability is mostly due to its articulations and skeletal components, which makes it diarthrodial.

It has been expected that around thirty percent of adults experience hip pain, and 10% of individuals may need hip replacement surgery.

The hip is a true diarthroidal ball-and-socket joint formed by the femur head joining the pelvic acetabulum. This joint, which is the main joint connecting the lower body to the trunk, often operates in a closed kinematic chain.

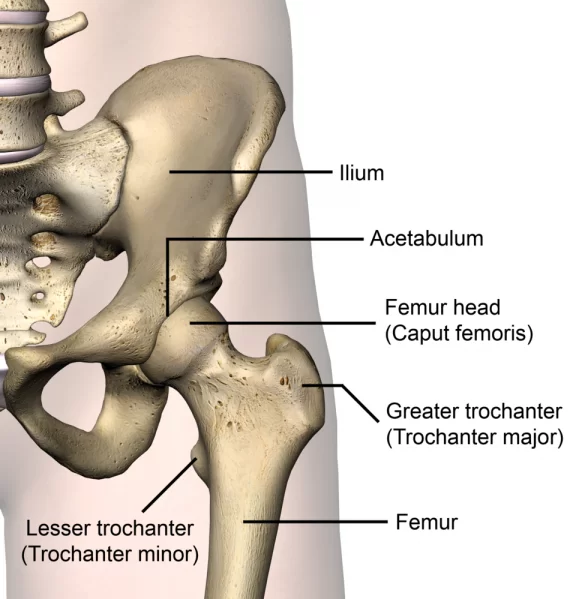

Anatomy of the Hip Joint

Each thigh bone encircles the hip joint. The thigh bones are located beneath the waist, where the thighs of the pants rest, and above the knees.

The region of your body closest to your waist is called the pelvis, where the thigh bone enters the hip bone.

- The hip joint remains in line with the axial skeleton of the leg muscles, femur, and pelvic articulations.

- When the lower leg was joined to the pelvic girdle, it was built for stability and weight support rather than for a broad range of motion.

- Ligaments—also called bands of tissue—keep the hip stable while the joint capsule forms by acting as an anchor for the ball in the socket.

- Bursae, sacs filled with fluid, act as shields in areas where muscles, tendons, and bones rub across one another.

Structures of the Hip Joint

The parts of your hip joint are as follows:

- These structures are formed by the smooth tissue that supports the top of your thigh bone and the acetabulum socket.

- This fabric acts as a cushion, lessening stress while you walk and move.

- The thin layer that separates the bones beneath your joint is called the synovium. It lets go of a lubricating fluid that makes it possible for your bones to move freely.

- Ligaments: The acetabulum and femur head are made up of fibrous tissue bands called ligaments.

- Muscle: The strong muscles in your hips allow for your movement. You have muscles in your hips that belong in your quadriceps, hamstrings, adductors, and gluteals.

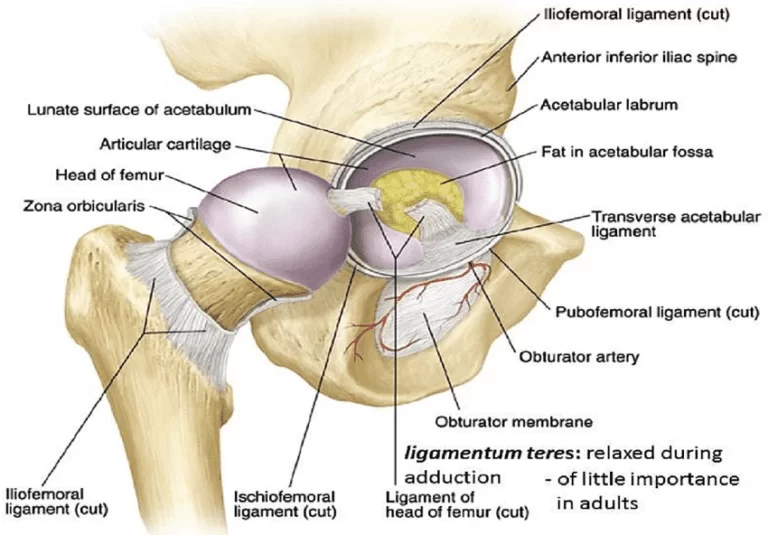

Articulating Surfaces

- The femur head and pelvic acetabulum move into an articulation related to the hip joint.

- In addition to being a fibrocartilaginous collar, the acetabular labrum is also used as a riser chamber.

- The acetabulum and femur head are composed of articular cartilage, which is denser than weight-bearing cartilage.

- The hip capsule protects the acetabulum.

- The femoral neck is connected posteriorly, and the intertrochanteric line is connected anteriorly using a distal approach.

The joint capsule of the Hip Joint

The transverse acetabular ligament’s outer fibrous layer and the proximal line of the acetabular rim function as guides during the acetabulum’s formation. The fibrous layer travels laterally to its distal attachment on the proximal femur from its acetabular attachment. It is important to remember that the femoral neck has both extracapsular and intracapsular regions.

A fragile capsule holds together its inferior and posterior loose joints. The longitudinal fibers on the fibrous capsule’s outside often spiral from the hip bone to the proximal femur. A collar developed by the deeper circular fibers that do not connect to any bones related to the femoral neck is called the zona orbicularis, also referred to as the annular ligament or the orbicular zone. The hip joint capsule’s growing inferior and posterior orientation is facilitated by the pubofemoral and iliofemoral ligaments.

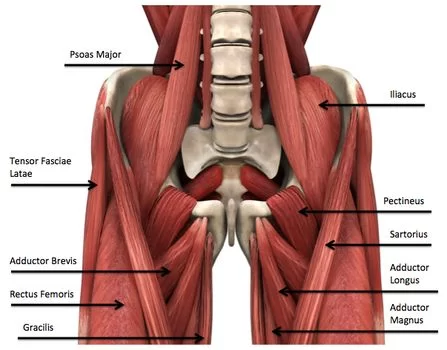

Muscles Around Hip Joint

The hip joint is the most movable in the human body. Stability, strength, and flexibility are provided by the hip muscles, which are found in the thigh, hip bones, and hip joint. Based on their location and use, these muscles can be defined together. There are three groups: the adductor, posterior, and abductor.

The anterior muscular group in the thigh contains the muscles responsible for hip flexion.

Gluteal muscles Group

The ilium’s attachment to the gluteal muscles gives it a function.

- Gluteus maximus

- Gluteus medius

- Gluteus minimus

- Tensor fasciae latae

Adductor group

This group involve

- Adductor brevis

- Adductor longus

- Adductor Magnus

- Pectineus

- Gracilis

Iliopsoas group:

The iliopsoas is created from the iliac and psoas major muscles.

Lateral rotator group

This group was formed up of

- Obturator externes

- Obturator internus

- Piriformis muscle

- Superior and inferior Gemelli

- Quadratus femoris. (These six start at the ilium’s acetabulum or lower and insert on or near the femur’s greater trochanter.)

Other Hip muscles:

The sartorius and rectus femoris aren’t typically considered hip muscles because they mainly move the knee but can also move the hip joint.

Additionally, the hamstring muscles facilitate hip extension. The tibia and fibula are utilized to assess the ischial tuberosity.

Embryology

Mesoderm opens to form the hip joint during weeks 4-6 of pregnancy. At seven weeks of gestation, when the femoral head and acetabulum are developed, cartilage cells gradually start to disappear. When a pregnancy reaches week eleven, the hip joint is mostly formed. The acetabular cartilage provides femoral head defense.

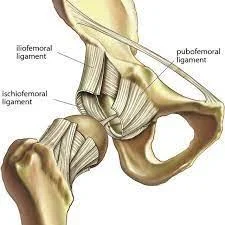

Ligaments of Hip Joint

Fibrous fibers called ligaments sustain the equilibrium of two bones.

The following ligaments protect the hip joint:

- The iliaofemoral ligament, which forms a Y shape, connects the femoral head to the pelvis at the front of the joint. It aids in decreasing hip hyperextension. The pubofemoral and iliofemoral ligaments divide the pubis into two separate sections.

- The ischium behind the acetabulum develops into the robust fibers that make up the ischofemoral ligament, which then connects the fibers of the joint capsule.

- The femur’s apex and the acetabulum are joined by the ligament teres, a small ligament. Though it doesn’t move at the hip, it does have a small artery that provides blood to part of the femoral head.

The hip joint’s ligaments function to provide stability. Two categories have differences extracapsular and intracapsular.

Intracapsular

- An intracapsular ligament is present only in the femur head ligament.

- The femur’s fovea and the acetabular fossa are where this little structure is associated.

- Blood is delivered to the hip joint by an obturator artery branch that travels to the femur’s head.

Extracapsular

- The iliofemoral ligament bifurcates from the anterior inferior iliac spine and attaches to the femur’s intertrochanteric line.

- In the shape of a “Y,” it keeps the hip joint from being overextended.

- Pubofemoral: Given anterior and inferior support for the capsule, this ligament fills the gap due to the femur’s intertrochanteric line and the superior pubic rami.

- A triangle-shaped structure limits excessive abduction and extension when the body rests.

- Hyperextension is avoided by the femoral head’s spiral path, which keeps it in the acetabulum.

Neurovascular Supply

- The acetabulum remains level and hyperextension is deterred by the spiral-shaped femoral head.

- Most of the arterial flow is brought in by the medial circumflex femoral artery, which the lateral circumflex femoral artery must traverse.

- The superior and inferior gluteal arteries, along with the head of the femur, obtain more oxygen from this artery.

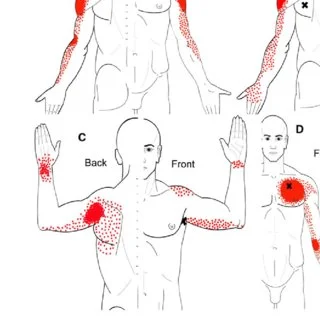

- The knee is innervated by these same nerves, which explains why pain can radiate from the hip to the knee or vice versa.

Blood Supply of Hip Joint

There are several ways in which the hip’s blood flow might change. The profound femoris, or deep artery of the thigh, disintegrates into the medial and lateral circumflex femoral arteries, which deliver blood.

Another anatomical feature that travels through the head of the femur ligament and derives from the posterior division of the obturator artery is called the foveal artery, additionally recognized as the artery resulting in the femur head.

There are two unusual anastomoses. The upper thigh is assisted by the cruciate anastomosis, whereas the trochanteric anastomosis preserves the femur head.

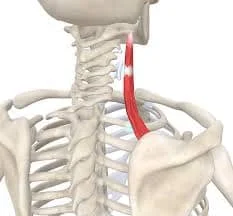

Innervation of Hip Joint

The articular branches of several nerves that arise from the lumbosacral plexus innervate the hip joint (L2-S1).

- The anterior side receives a supply of blood flow from the femoral nerve.

- Part of the inferior appearance is connected to the obturator nerve.

- The position was brought about via the superior side gluteal nerve.

Though primary hip pain may be referred to the knee due to similar innervation, it is vital to recognize that pain sensations originating from the vertebral column can also be felt in the hip joint.

Lymphatics Drainage

The anterior aspect gives lymphatic drainage to the deep inguinal nodes, while the medial and posterior aspects offer lymphatic drainage to the internal iliac nodes.

Nerves Supply

The hip joint is where the nerves that nourish the femur, gluteal, and obturator muscles attach.

Stabilizing Factors

The hip joint is mostly used to support weight. Several elements contribute to the joint’s increased stability.

The acetabulum is the initial structure. In addition to covering almost the whole femur head, it is deep. As a result, there is a decreased chance that the head will slip out of the acetabulum.

This structure, known as the acetabular labrum, is a fibrocartilaginous ring that encircles and grows thicker than the acetabulum. The increased depth allows for a larger articular surface, which improves the joint’s stability even more.

The enlarged joint capsule and the powerful iliofemoral, pubofemoral, and ischiofemoral ligaments offer high stability. Because of their unusual spiral orientation, these ligaments tighten when the joint is extended.

Together, the hip joint’s ligaments and muscles perform the following functions:

- The medial flexors, which are situated anteriorly, are weaker and less numerous whereas the ligaments are stronger.

- They can “pull” the femur head into the acetabulum because the medial rotators are more powerful and numerous posteriorly, where the ligaments are weakest.

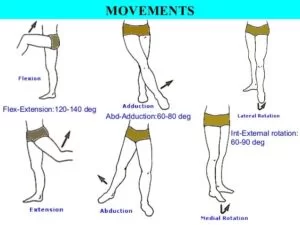

Movement of the Hip Joint

A list of activities that can be performed at the hip joint is shown below, along with the primary muscles necessary for each movement:

- Flexion – iliopsoas,

- Rectus femoris, sartorius, pectineus

- The semitendinosus, gluteus maximus, biceps femoris, and semimembranosus come together to form the hamstrings, often known as extensions.

- The muscles involved in abduction belong to the piriformis, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fascia lata.

- The adductors gracilis, pectineus, magnus, brevis, and longus contract during adduction.

- The biceps femoris, gluteus maximus, and piriformis, along with the quadratus femoris, obturators, and gemilli, are all beneficial in lateral rotation.

- The anterior fascial lata, the gluteus medius and minimus anterior fibers, and the medial rotation

- Increased flexion of the hips results from the hamstrings’ expansion and relaxation when the knee is bent.

- During extension, these parts tense up to avoid further motion.

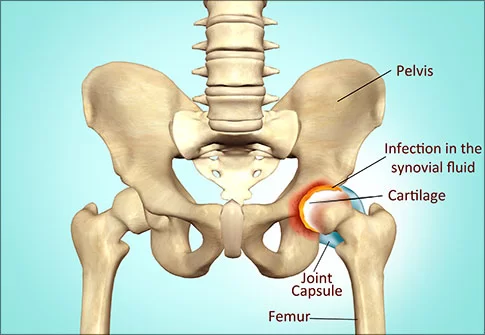

Clinical Significances

- Osteoarthritis: A degenerative illness that results in the hip joint’s cartilage tearing down, causing discomfort, stiffness, and a restricted range of motion. It is one of the primary reasons why older people have hip discomfort.

- Hip fractures: These fractures, which are particularly common in the elderly, typically come on by falls and can result in catastrophic consequences, such as lifelong impairment.

- Hip labral tears: The labrum, the cartilage wrapping around the hip socket, could develop tears that bring about discomfort and instability. Trauma or degenerative changes could be the reason for them.

- Hip impingement (also known as femoroacetabular impingement, or FAI) is a condition that can cause injury and discomfort to the joints when there is an imbalance between the femur and the hip socket.

FAQs

What’s the full term for the joint in the hip?

Supporting the body’s weight during both static (like standing) and dynamic (like walking or sprinting) motions is the main responsibility of the hip joint. It is officially known as the acetabular femoral joint (art. coxae).

What makes the hip joint crucial?

The hip joint retains the stresses that accompany daily tasks while facilitating stability and balance for mobility. When walking or standing, the hip operates as a multiaxial ball-and-socket joint, which applies pressure on the skeletal muscles in the upper limbs.

The two hip bones are which?

Following the femur, or thigh bone, which forms the pelvis, are the pubis, ischium, and ilium bones.

What kind of hip joint is it?

Among its components is the hip’s ball and socket joint. The long bone with an inclined end is called the femur. Your femur is forced forward by the rounded end of the acetabulum, which forms a cup-shaped socket with your pelvis. This type of joint facilitates a broad range of motion and maintains your body’s equilibrium with your legs.

Which joint is the strongest in your body?

In the human anatomy, the hip joint is the most important and often used joint.

It has been used regularly. When a joint is overused, it starts to adapt by pulling on the nearby muscles, ligaments, and tendons.

Degeneration/ Osteoarthritis (OA)

Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI)

References

- Physiotherapist, N. P. (2023a, December 13). Hip Joint: Anatomy, Movement, Function, Importance. Mobile Physiotherapy Clinic. https://mobilephysiotherapyclinic.in/hip-joint/

- Dhameliya, N. (2023, August 10). Hip Joint – Anatomy, Structure, Function. Samarpan Physiotherapy Clinic. https://samarpanphysioclinic.com/hip-joint/

- Professional, C. C. M. (2024, May 1). Hip Joint. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/24675-hip-joint

- Hip joint. (2023, October 30). Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/hip-joint

- 3D videos of normal hip joint anatomy and total hip replacement in Houston, Texas. https://www.stefankreuzermd.com/hip-anatomy.html

14 Comments