Hip Flexor Muscles

Overview

- A hip flexor muscle flexes the hip or brings the knee closer to the chest. Hip flexion function is maximized with a high, forward kick that elevates the leg above the waist. Every step you take activates your hip flexor muscles.

- They are necessary to keep the posterior pelvic muscles balanced.

- A strong core muscle is one way to strengthen hip flexors and improve posture.

- Stretching these muscles will increase their length and help prevent injury.

- The hip flexors consist of five key muscles that contribute to hip flexion: the iliacus, psoas, pectineus, rectus femoris, and sartorius.

Anatomical variation

Prime movers

The primary movers for hip flexion are:

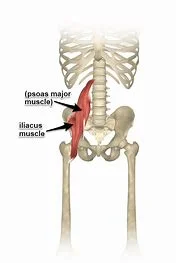

- Psoas major is a long, fusiform muscle that originates on either side of the spine and inserts at the lesser trochanter of the femur. When the hip moves into flexion, the psoas muscle contracts. The psoas minor muscle is a normal anatomical variant found in roughly 60% of people.

- Iliacus muscle. The iliacus muscle is a triangular sheet that connects the ilium bone and the lesser trochanter.

- The iliacus and psoas muscles are also referred to as the iliopsoas musculotendinous unit due to their overlapping action and anatomical proximity. The iliopsoas are connected to the hip capsule or pubis by an associated bursa, which is the largest bursa in the body.

- These two muscles help to maintain postural stability while standing upright and elevating the torso from a supine position.

- The iliopsoas muscle is the body’s primary hip flexor. People who spend the majority of their day sitting have shorter hip flexor muscles, which tilt the pelvis and affect how they walk. See Sitting Ergonomics and Their Impact on Low Back Pain

Synergist

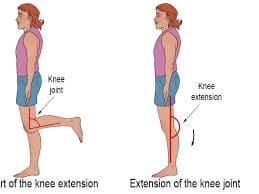

The rectus femoris is a quadriceps and hip flexor muscle with two functions: hip flexion and knee extension. When both actions are happening at the same time, such as kicking a soccer ball and swinging a straight leg forward, the Rectus Femoris is extremely active.

The sartorius muscle, the longest in the body, connects the hip and knee joints. It originates at the anterior superior iliac spine and attaches to the pes anserinus as a broad fascial insertion. It flexes the hip, adducts the thigh, and externally rotates the leg. Sartorius’s muscle, like the Rectus Femoris, requires a lot of effort during a soccer kick, especially when kicking across the body.

The pectineus muscle is a hip flexor and secondary adductor, with its origin on the superior pubic ramus and insertion on the pectineal line of the femur.

Iliopsoas muscle

The iliopsoas is a compound muscle composed of the iliac and psoas muscles.

The iliopsoas muscle complex consists of three muscles: the iliacus, psoas major, and psoas minor. This complex muscle system can function as a unit or as individual muscles.

The iliopsoas muscle is the strongest hip flexor, assisting in the external rotation of the femur and playing a critical role in maintaining hip joint strength and integrity. It is necessary for proper lumbar posture while standing or sitting, as well as when walking or running.

The fascia covering the iliopsoas muscle forms more fascial connections, connecting the muscle to various viscera and muscle portions.

The iliopsoas can be the source of a variety of problems. These conditions can cause pain, weakness, and difficulty performing basic tasks like walking, running, and getting up from a supine position.

Iliacus muscle

The iliacus muscle has a triangle shape, is flat, and fits perfectly into the iliac fossa, which is the curved surface of the largest pelvic bone. It is also known as the iliopsoas muscle, which is associated with the psoas major muscle. This muscle is attached to the iliac fossa about two-thirds of the way from the top. Another section is attached to the inside of the iliac crest, which is the top, outer portion of the pelvis bone.

Other fibers of the iliaccus muscle are attached to the iliolumbar and anterior sacroiliac ligaments (located at the base of the sacrum), as well as the anterior iliac spine. The iliacus muscle fibers then converge and insert the tendon on the outer side of the psoas major muscle, which extends from the lumbar spine in the lower back to the lower pelvis. Many of these fibers connect to the femur or thigh bone.

Origin:

Upper two-thirds of the iliac fossa of ilium, internal lip of iliac crest, lateral aspect of sacrum, ventral sacroiliac ligament, and lower part of the iliolumbar ligament.

Insertion:

Femur’s lesser trochanter. Its fibers are also inserted in front of the psoas major, extending distally over the lesser trochanter.

Structure:

The iliacus arises from the iliac fossa on the interior part of the hip bone, as well as from the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS). It joins the psoas major to create the iliopsoas. It starts at the iliopubic eminence and travels through the muscular lacuna to its insertion on the lesser trochanter of the femur. The iliacus fibers are also inserted in front of the psoas major and extend distally over the lesser trochanter.

Function:

- The iliacus rotates and flexes the femur externally.

- It is also one of the most important muscles for maintaining proper posture.

- When combined with the psoas muscle, these two muscles are considered the strongest hip flexors in the body.

- It is also one of the most important muscles for maintaining proper posture.

- The Iliacus muscle can attach to an anterior tilt of the pelvis down and forward.

- The iliopsoas, like the iliacus, are controlled for hip flexion. This muscle is also involved in trunk flexion, which is the forward bending of the trunk, as seen when performing a sit-up and bending down to tie your shoes.

- The iliacus is also constantly active while walking, whereas the psoas major is only active during the gait’s preceding and early swing phases.

The iliacus muscle eccentrically controls the trunk’s lateral bending.

Relation:

The iliac fascia covers the anterior part of the pelvic portion of the iliacus muscle, separating it from the peritoneum. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, the cecum on the right, and the iliac part of the descending colon on the left all cross the surface of the iliacus. The iliacus muscle’s medial margin corresponds to the femoral nerve and the psoas major muscle’s lateral margin.

The iliacus muscle’s anterior thigh portion is posterior to the fascia lata, rectus femoris, and sartorius muscles. It crosses the deep femoral artery. The posterior part of the iliacus is adjacent to the hip joint and separated by a large subtendinous iliac bursa.

Nerve Supply:

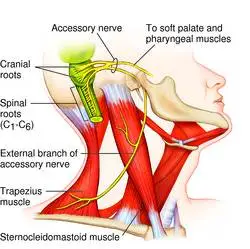

The iliacus muscle is innervated by nerves from the second and third nerves of the lumbar area via the femoral nerve. (L2, L3)

Blood Supply:

The iliolumbar artery innervates the iliacus, just as it does the psoas major muscle. It collects blood from the deep circumflex iliac, obturator, and femoral arteries.

Assessment:

- Palpation: The patient is supine, with a pillow under his knees. Flex the knee and slightly laterally rotate. Place the palpating hand on the anterior iliac crest and use the fingertips to palpate the iliac fossa. The majority of the iliacus is not palpable. Ask the patient to flex their thigh at the hip joint and feel for iliac muscle contraction.

- Tightness: The patient stands against a wall, heels apart, shoulders and head touching the wall. Normal is the ability to posteriorly tilt and touch the small of the back rather than the wall. If the patient is unable to posterior tilt by flattening their back against the wall with their feet apart and their hips and knees straight but can do so with their knees bent and their hip flexed, the restriction could be shortened iliacus.

Psoas major muscle

The psoas muscle is a paraspinal muscle located deep within the body, close to the spine and the brim of the lesser pelvis. At the distal end, it joins the iliacus muscle to form the iliopsoas muscle. This depth, combined with the fact that the psoas originate from the sides of the five lumbar vertebrae, makes it an important factor in back health.

It also works to laterally flex the lumbar spine while stabilizing and flexing the thigh.

It is essential for correct standing and sitting lumbar posture, hip joint stability, and while walking and running.

Origin & Insertion:

The psoas major has a large muscle located immediately lateral to the vertebral column. It originated from:

- Transverse processes of all lumbar vertebrae.

- Vertebral bodies from T12 to L5.

- intervening intervertebral discs

- The fibers of the psoas major extend inferolaterally from the lesser pelvis to the thighs. They travel along the pelvic brim and below the inguinal ligament before merging into the anterior thigh. The iliopsoas muscle is formed when the psoas major muscle’s lateral fibers fuse with the iliacus muscle’s fibers. The iliopsoas inserts in the lesser trochanter of the femur after passing deep into the inguinal ligament & anterior to the hip joint capsule.

Structure:

The psoas major is divided into two parts: superficial and deep. The deep part is formed by the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae L1–L5. The superficial part is formed by the lateral surfaces of the last thoracic vertebra, lumbar vertebrae L1–L4, and the adjacent intervertebral discs. The lumbar plexus is located between two layers.

The iliac fascia surrounds the iliopsoas, which are made up of the iliacus muscle and the psoas major. The iliopsoas muscle extends from the iliopubic eminence through the muscular lacuna to its insertion on the lesser trochanter of the femur. The iliopectineal bursa, located at the iliopubic eminence, separates the iliopsoas muscle tendon from the external part of the hip capsule. The iliac subtendinous bursa is located between the iliopsoas attachment and the lesser trochanter.

Variation:

Less than half of all human subjects have both the psoas major and psoas minor muscles.

Function:

The psoas’ major muscle functions are as follows:

- To connect the upper body to the lower body, the outside to the inside, the appendicular to the axial skeleton, and the front to the back via the fascial relationship.

- The psoas, when combined with the iliopsoas muscle, contribute significantly to hip joint flexion in a supine or standing position.

- Stabilizes the lumbar spine while sitting.

- Work as a femoral head stabilizer in the hip acetabulum for the first 15 degrees of motion.

- Unilateral contraction of the psoas aids in lateral motions, while bilateral contraction can help elevate the trunk from the supine position.

- The psoas muscle also works with the hip flexors to elevate the upper leg towards the body when the body is stationary and pull the body towards when the leg is fixed.

Relation:

The superior psoas major muscle lies behind the diaphragm. The abdominal aorta is located on the left side, medial to the psoas major. Other muscle-related retroperitoneal structures include the kidneys as well as ureters, gonadal vessels, and the genitofemoral nerve.

Because it is located immediately lateral to the vertebral column, the roots of the lumbar plexus become embedded in the belly of the psoas major as they exit the spinal canal. The plexus develops in the muscle, and its branches emerge from its lateral border.

The psoas major muscle in the thigh helps to form the base of the femoral triangle. The iliopsoas tendon is located deep in the fascia lata, sartorius, rectus femoris, and deep femoral artery. The iliac bursa originates from the hip joint capsule.

Blood supply:

- The psoas major muscle is primarily innervated from the iliolumbar branch of the internal iliac artery. The lumbar branches of the aorta, or as the obturator branch of the internal iliac artery, as well as branches of the external iliac and femoral arteries, contribute to the blood supply.

- The venous drainage of the psoas major mirrors the arterial supply. It returns to the femoral, internal, and external iliac veins, as well as the inferior vena cava.

Nerve supply:

Branches of the ventral rami of the lumbar spinal nerves (L1, L2, & L3) join to form the lumbar plexus. The lumbar plexus is implanted within the Psoas major muscle and its branches emerge from there.

Psoas minor muscle

- The psoas minor muscle is a thin, paired muscle located in the posterior abdominal and pelvic region. It is located on the anterior part of the psoas major muscle, but it does not extend past the inguinal ligament. Despite its close relationship with the psoas major muscle, the psoas minor is not considered part of the iliopsoas muscle complex.

- The psoas minor muscle is inconsistent and only found in a subset of the population. When present, it acts on the lumbar spine to cause a weak flexion of the trunk.

Origin & Insertion:

- The psoas minor muscle originates from the lateral aspect of the bodies of the T12 and L1 vertebrae, as well as the intervertebral disc that connects them.

- The muscle then stretches inferiorly and tapers into a long, flat tendon that is frequently longer than the muscle belly.

- The tendon attaches to the pecten pubis, pectineal line of pubis, and iliopubic eminence via a thickened fascia band known as the iliopectineal arch.

Structure:

- The psoas minor muscle originates from vertical fascicles inserted on the last thoracic and first lumbar vertebrae. From there, it descends to the medial border of the psoas major and enters the innominate line and iliopectineal eminence. It also attaches to and stretches the deep surface of the iliac fascia, with its lowermost fibers occasionally reaching the inguinal ligament. It is located posterolateral to the iliopsoas muscle. Variations occur, and the insertion of the iliopubic eminence frequently radiates into the iliopectineal arch.

- The psoas minor muscle receives oxygenated blood from the four lumbar arteries beneath the subcostal artery and the lumbar branch of the iliolumbar artery.

Function:

The psoas minor is a very weak muscle, and its absence does not reduce the body’s functionality, so its exact function is unclear. However, it is believed to aid in trunk flexion, allowing a person to bend forward at the lumbar spine.

Relation:

The psoas minor muscle is located entirely on the anterior surface of the psoas major muscle and thus shares many of its anterior relationships. The most distal end of the ileum crosses the right psoas minor, which is posterior to the inferior vena cava, while the colon crosses the left psoas minor.

The sympathetic trunk and aortic lymph nodes are connected to the muscle along its anteromedial border.

Nerve Supply:

The psoas minor muscle gets its supply directly from the lumbar spinal nerves.

Variation:

The psoas minor muscle is considered inconstant and absent, appearing in only 40% of the human specimens studied. It has an average length of 24 cm, with 7.1 cm of muscle tissue and 17 cm of tendon.

Blood Supply:

The lumbar arteries provide the majority of the vascular supply for the psoas minor muscle. The psoas major muscle’s blood supply network, on the other hand, makes numerous minor contributions. This may include branches from the iliolumbar, obturator, external iliac, and femoral arteries.

Pectineus muscle

The pectineus is a flat muscle located in the superomedial region of the anterior thigh. The fascial portion of the thigh muscles is distinct in that each is innervated by a femoral nerve (L2, L3). Because of its dual nerve supply, the pectineus is one of only a few muscles that can be classified into two compartments at once: anterior and medial. The others are adductor longus and adductor magnus.

For didactic purposes, the pectineus is typically described alongside the five muscles of the medial compartment of the thigh. These muscles are: gracilis, adductor longus, adductor brevis, and adductor Magnus. This muscle belongs to the functional group of the Hip adductors muscle.

In addition to adducting the thigh, the pectineus muscle performs thigh flexion, external (lateral) rotation, and internal (medial) rotation. Aside from being a prime mover, the pectineus is also a postural muscle, stabilizing the pelvis and balancing the trunk on the lower extremities while walking.

Origin:

pectineal line and adjacent bone of the pelvis

Insertion:

The oblique line that runs from the base of the lesser trochanter to the linea aspera on the femur’s posterior surface.

Nerve Supply:

- The pectineus is primarily supplied by the femoral nerve (L2, L3). However, in some people, the pectineus may be innervated by two separate lumbar plexus nerves.

- This composite innervation reflects the pectineus’s compartmentalization into the anterior and medial compartments of the thigh. In these cases, the femoral nerve (L2, L3) supplies the anterior part of the muscle, as is typical of anterior thigh muscles. A branch of the obturator nerve (L3, L4) innervates the smaller, posterior part of the muscle.

Blood Supply:

The medial circumflex femoral artery, a branch of the femoral artery, supplies the muscle’s superficial portion. The deep part of the muscle is vascularized by the anterior branch of the obturator artery, which is a branch of the internal iliac artery.

Function:

When the pectineus contracts, its fibers flex and adduct the thigh at the hip joint. When the lower limb is in its anatomical position, muscle contraction causes flexion of the hip joint. This flexion can extend as far as the thigh, at a 45-degree angle to the hip joint.

At that point, the fibers are angled so that the contracted muscle fibers pull the thigh toward the midline, resulting in thigh adduction. Crossing your legs at the knee or ankle is a sequential movement that involves both pectineus muscle actions. Hip flexion is a single action that, when combined with the psoas major, iliacus, rectus femoris, and sartorius, allows for the gait cycle to continue.

According to some sources, the pectineus muscle contributes to both external and internal thigh rotation. This is still hotly debated, but the fact that the pectineus insertion is lateral to the midline, beyond the femur’s mechanical axis of rotation, suggests that the argument may have some merit.

This muscle is not only the primary mover, but it also helps to stabilize the pelvis. It is proposed that all of the muscles connecting the pelvis and the proximal femur function as adaptable ligaments of the hip joint, preserving its integrity during body movements.

Structure:

The pectineus muscle arises from the pectineal line of the pubis and, to a lesser extent, from the surface of the bone in front of it, between the iliopectineal eminence and pubic tubercle, as well as from the fascia covering the anterior surface of the muscle; the fibers pass downward, backward, and lateral to be inserted into the pectineal the lateral is inserted in the pectineal line on the femur, which runs via the lesser trochanter into the linea Aspera.

Relation:

- The muscle is in the same plane and medially to the adductor longus. Laterally, it is linked to the psoas major muscle and the medial circumflex femoral artery and vein.

- The anterior surface of the pectineus, along with the adductor longus, forms the medial part of the femoral triangle’s floor, while the iliacus and psoas major make up the lateral side. This surface of the pectineus is covered in a deep layer of fascia lata that separates it from the femoral artery, femoral vein, and great saphenous vein that runs through the femoral triangle.

- The adductor magnus, adductor brevis, and obturator externus muscles are located posterior to the pectineus, as is the anterior branch of the obturator nerve. The fascia lata surrounds the anterior and posterior thigh compartments. These two are internally divided by medial and lateral intermuscular septa that connect to the femur. Although the adductor (medial) compartment, which includes the pectineus, lacks its fascial border to distinguish it from the anterior and posterior compartments, it is still described separately due to the common function and muscular innervation of its constituents.

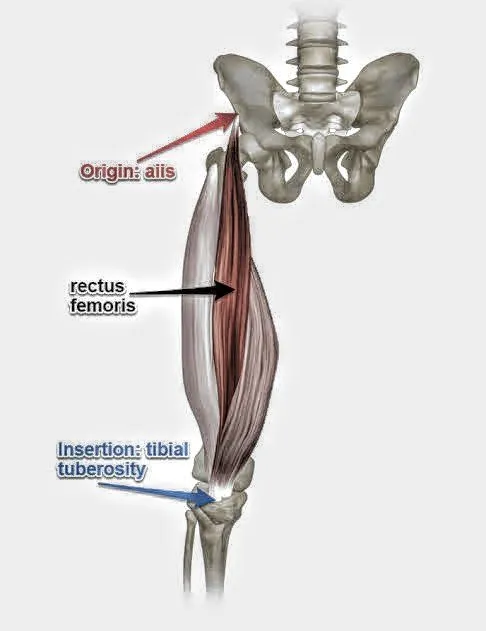

Rectus femoris muscle

The Rectus femoris muscle has a fusiform shape and is part of the quadriceps muscle. It is a large muscle located in the superior, anterior middle

compartment of the thigh and is the only quadriceps muscle to cross the hip.

Along with the superior-medial section of the vastus lateralis and vastus medialis, it is superior to and rests above the vastus intermedius muscle.

The word rectus is a Latin word that means straight. Thus, the rectus femoris gets its name from the fact that it runs straight down the thighs.

It is a two-way acting muscle that crosses over the hip and knee joints, allowing it to extend the knee while also assisting the iliopsoas in hip flexion. It’s also a hip flexor muscle.

A short rectus femoris may result in a higher-positioned patella compared to the contralateral side. Knee flexion less than 80° or a prominent superior patellar groove indicates a significantly shortened rectus femoris muscle.

Origin:

Rectus femoris muscle originates from the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) and a portion of the ilium superior to the acetabulum.

It has a proximal tendinous complex that consists of a direct tendon, an indirect tendon, and a variable third head. Finally, the direct and indirect tendons come together to form a common tendon.

There is a membrane that connects the CT to the anterior superior iliac spine.

Insertion:

Rectus Femoris muscle, along with vastus medialis, vastus lateralis, and vastus intermedius, joins the quadriceps tendon and inserts at the patella and tibial tuberosity via the patellar ligament.

Structure:

It is derived from two tendons: the anterior, or straight, from the anterior inferior iliac spine, and the posterior, or reflected, from a groove above the rim of the acetabulum.

The two connect at an acute angle and form an aponeurosis that extends downward on the muscle’s anterior surface, from which muscular fibers emerge.

The muscle ends in a broad and thick aponeurosis that occupies the lower two-thirds of its posterior surface before gradually narrowing into a flattened tendon and inserting into the base of the patella.

Function:

The thigh’s hip flexors are the rectus femoris, sartorius, and iliopsoas muscles. When the knee is extended, the rectus femoris muscle is a weaker hip flexor because it is already shortened, resulting in active insufficiency; the action will recruit more iliacus muscle, psoas major muscle, tensor fasciae latae, and the remaining hip flexors than the rectus femoris.

Similarly, the rectus femoris muscle is not dominant in knee extension when the hip is flexed because it is already shortened, resulting in active insufficiency. In essence, the vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius are primarily responsible for knee extension from a seated position, with the rectus femoris playing a minor role.

In contrast, passive insufficiency can impair the muscle’s ability to flex the hip and extend the knee in a position of full hip extension and knee flexion.

The rectus femoris muscle is a direct antagonist of the hamstring muscle at the hip and knee.

Relation:

The rectus femoris muscle’s proximal portion is located deep within the tensor fasciae latae, sartorius, and iliacus muscles. All of the contents of the thigh’s anterior compartment are deep within the rectus femoris. These include the hip joint capsule, vastus intermedius, the anterior margins of vastus lateralis and vastus intermedius, the lateral circumflex femoral artery, and some femoral nerve branches.

Nerve Supply:

The neurons for voluntary thigh contraction emerge near the summit of the medial side of the precentral gyrus (the brain’s primary motor area).

These neurons transmit a nerve signal via the corticospinal tract to the brainstem as well as the spinal cord. Upper motor neurons initiate the signal and travel through the precentral gyrus to the internal capsule, cerebral peduncle, and medulla. The corticospinal tract divides into the lateral corticospinal tract within the medullary pyramid. The nerve signal will travel down the lateral corticospinal tract up to reaching spinal nerve L4. The nerve signal will travel from the upper motor neurons to the lower motor neurons. The signal will travel through the anterior root of L4 and the anterior rami of the L4 nerve before exiting the spinal cord via the lumbar plexus. posterior branch of the L4 root acts as the femoral nerve. The quadriceps femoris supplies the femoral nerve, with the rectus femoris acting as its fourth branch. When the signal from the medial side of the precentral gyrus reaches the rectus femoris, it contracts & extends the knee while flexing the thigh at the hip.

Blood Supply:

The quadriceps artery supplies the rectus femoris muscle and can originate from three sources: the femoral, deep femoral, and lateral circumflex femoral arteries. The lateral circumflex femoral and superficial circumflex iliac arteries also contribute to the blood supply of the rectus femoris, though to a lesser extent.

Assessment:

- Palpation: The most superior quadriceps muscle, the rectus femoris, can be palpated. The rectus femoris muscle can be palpated at the anterior inferior iliac spine until it reaches the quadriceps tendon’s insertion. To identify the muscle belly, ask the person to contract the quadriceps muscle isometrically.

- Strength: To assess muscle strength for the Rectus Femoris, including the rest of the quadriceps group muscle position, the patient sits with the hip and knee flexed to 90° for grades 5, 4, and 3, while grade 2 is assessed in side-lying position with the test limb uppermost and the knee flexed to 90°.

Other Tests:

In rectus femoris injury:

- Ely’s test: illicit pain on the tightness

- FABER (Patrick’s test): illicit no pain.

- Pain occurs during resisted hip flexion.

- Shortness of the Rectus femoris reduces knee ROM below 80°, and the patella grove becomes

Sartorius muscle

The sartorius muscle is found on both sides of the body, beginning at the anterior superior iliac spine of the pelvis. The sartorius muscle begins at the front of the thigh and angles inward before ending on the medial side of the tibia.

Because the sartorius muscle runs through two joints, the hip, and the knee, it affects motion at both. The actions of the sartorius include:

- Hip flexion: Flexing at the hip, as a person marches in place with high knees.

- Hip abduction: Dragging your leg away from your midline, as when you take a step to the side.

- External hip rotation: Turning the leg outside so the thigh, knee, and toes face the side of the room.

- Knee flexion: Flexing the knee to move the heel closer to the glutes.

- The tree poses in yoga are an example of an exercise that requires all sartorius actions. To move the foot upward in the tree pose, flex the hips and knees.

- To place the bottom of the raised foot on the inside of the stationary leg, abduct and rotate the hip outward in the room. Cross-legged sitting is also an excellent demonstration of sartorius muscle action.

Origin & Insertion:

The sartorius muscle arises from a round tendon from the anterior superior iliac spine and the upper half of the notch that connects the anterior superior iliac crest and the anterior inferior iliac spine. The fibers form a thin, flat muscle that runs anteromedially across the anterior surface of the thigh.

The muscle descends almost vertically from the medial side of the thigh. It crosses the medial side of the knee joint and attaches to the medial side of the proximal tibia, anterior to the gracilis and semitendinosus muscles.

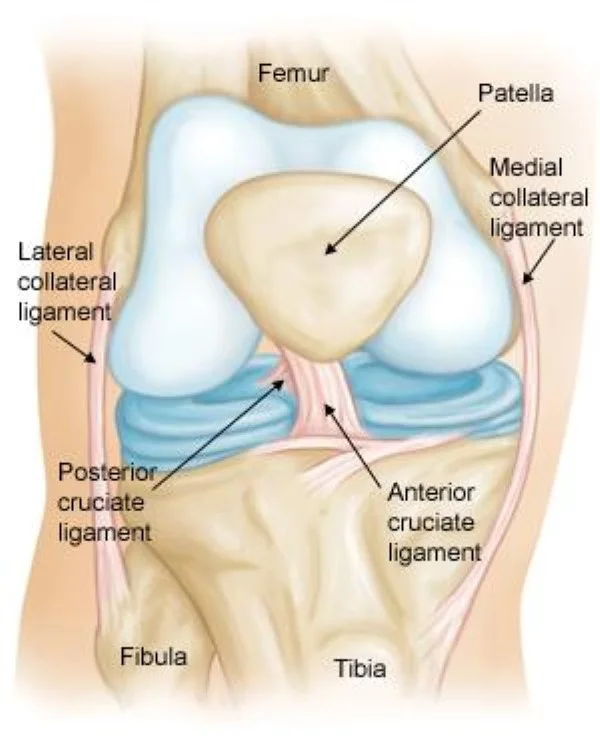

The inserting tendons of these three muscles form a broad aponeurotic sheath known as the pes anserinus. Some fibers from the inferior portion of the tendon merge with the medial collateral ligament of the knee joint and the deep fascia over the medial aspect of the leg, whereas some superior fibers merge with the knee joint capsule. These connections help to maintain the medial stability at the knee joint.

Structure:

The sartorius muscle originates from the anterior superior iliac spine and a portion of the notch that connects the anterior superior iliac crest and anterior inferior iliac spine. It runs obliquely across the upper and anterior thigh in an anteromedial direction.

It goes behind the femur’s medial condyle and ends in a tendon. This tendon curves anteriorly to connect the gracilis and semitendinosus muscles in the pes anserine, where it inserts into the tibia’s superomedial surface.

Its upper part forms the lateral border of the femoral triangle, and the point at which it crosses the adductor longus defines its apex.

The adductor canal runs deep into the sartorius and its fascia, carrying the saphenous nerve, femoral artery and vein, and nerve to the vastus medialis.

Function:

The hip flexes slightly, abducts, as well as rotates the thigh laterally. It can flex the leg at the knee, as well as turn the leg medially.

This muscle is essential for pelvic stability, particularly in women. This is due to the constricting effect that the muscles on both sides of the body have on the pubic symphysis.

Relation:

The sartorius muscle is located superficially in the thigh, with only fascia and skin covering its surface. The quadriceps femoris muscle is located deep in the sartorius muscle.

The sartorius muscle passes through the iliopsoas, pectineus, and adductor longus muscles as it moves from the lateral to the medial side of the thigh. The tensor fasciae latae muscle is located just lateral to the sartorius muscle’s proximal attachment.

The medial edge of the sartorius muscle serves as the lateral border of the femoral triangle, a large anatomical space. The inguinal ligament and the medial margin of the adductor longus muscle complete the triangle superiorly and medially, respectively. The femoral artery, vein, and nerve are located medial to the sartorius. The femoral artery continues inferiorly, deep into the sartorius.

Nerve Supply:

The femoral nerve supplies the sartorius, as it does all of the muscles in the anterior compartment of the thigh.

Variation:

- It can develop from the outer end of the inguinal ligament, the notch of the ilium, the ilio-pectineal line, or the pubis.

- The muscle can be divided into two parts, with one being inserted into the fascia lata, femur, patellar ligament, or semitendinosus tendon.

- The insertion tendon may end in the fascia lata, the knee capsule, or the leg fascia.

Some people may not have the muscle.

Blood supply:

- As the sartorius muscle is so long, it comes as no surprise that it requires extensive vascular supply from several sources:

- The proximal third may receive vascular supply from branches of the femoral, deep femoral, lateral circumflex femoral, and/or quadriceps arteries.

- The femoral artery’s branches supply the middle third.

- The distal third receives blood supply from the femoral and descending genicular arteries.

Embryology

The embryology of the hip flexor muscles is the study of how these muscles develop from the beginning of life. The hip flexor muscles are the iliopsoas, pectineus, rectus femoris, and sartorius. These muscles are responsible for flexing the hip joint as well as bringing the thigh near to the chest.

The hip flexor muscles grow from the paraxial mesoderm, a layer of cells that forms through the sides of the embryo. The paraxial mesoderm differentiates into somites, which form the body’s skeletal, muscular, and dermal tissues. The somites are also divided into sclerotomes, which produce the bones as well as cartilage, & dermomyotomes, which form the skin and muscles.

The hip flexor muscles are derived from the myotomes, which are muscular portions of the dermomyotomes. Myotomes form pairs along the vertebral column as well as extend in the limb buds, which are the precursors of the arms and legs. The myotomes of the lower limb bud are classified into three regions: dorsal, ventral, and intermediate. The dorsal region forms the extensor muscles of the leg; the ventral region forms the flexor muscles of the leg; and the intermediate region develops the adductor muscles of the leg.

The iliopsoas muscle is formed by the combined muscles of the iliacus and psoas major. The iliacus muscle develops from ventral myotomes in the lumbar and sacral regions. The psoas major muscle develops from ventral myotomes in the thoracic and lumbar regions. The two muscles connect and insert on the lesser trochanter of the femur.

The pectineus muscle grows from the middle myotomes of the lumbar region. It comes from the superior ramus of the pubis and also inserts on the pectineal line of the femur.

The rectus femoris muscle arises in the ventral myotomes in the lumbar region. It originates from the anterior inferior iliac spine and ilium and attaches to the patella and tibial tuberosity. This is the only quadriceps muscle that crosses the hip joint.

The sartorius muscle develops from ventral myotomes in the lumbar and sacral regions. It emerges from the anterior superior iliac spine & attaches to the medial surface of the tibia. It is the longest muscle in the body, running obliquely across the thigh.

Lymphatic Drainage of Hip flexor muscles

Lymphatic drainage is the process by which the lymphatic system removes excess fluid and waste from tissues. The hip flexor muscles are a group of muscles that help to flex the hip joint and bring the thigh closer to the chest. They consist of the iliacus, psoas, pectineus, rectus femoris, and sartorius muscles.

The lymphatic drainage to the hip flexor muscles is described below:

- The iliacus muscle drains into the external iliac lymph nodes, which are situated along the external iliac artery and vein in the pelvis.

- The psoas major and minor muscles drain into the lumbar lymph nodes, which are found in the lower back near the abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava.

- The psoas major & minor muscles drain into the lumbar lymph nodes, which are found in the lower back near the abdominal aorta and inferior vena cava.

The pectineus muscle drains into the superficial inguinal lymph nodes, which are found in the groin near the inguinal ligament. - The rectus femoris muscle drains into the deep inguinal lymph nodes, which are located near the inguinal ligament and femoral vessels.

The sartorius muscle drains into both superficial and deep inguinal lymph nodes, depending on where it originates and inserts.

The lymphatic system drains tissue fluid, plasma proteins, and other cellular debris back into the bloodstream while also playing a role in immune defence. Lymph is formed when a collection of substances enters lymphatic vessels; lymph nodes filter the lymph and direct it into the venous system.

Lymphatic vessels

The lymphatic vessels of the lower limb are divided into two categories: superficial vessels and deep vessels. They are distributed similarly to the veins of the lower limb.

Superficial lymphatic vessels

The superficial vessels are divided into two major categories: (i) medial vessels, that closely follow the course of the great saphenous vein, and (ii) lateral vessels, that are more closely connected with the small saphenous vein.

Medial Vessels

The medial group begins at the dorsal surface of the foot. They travel up the anterior & posterior aspects of the medial lower leg alongside the great saphenous vein, passing behind the femur’s medial condyle. This group of vessels terminates in the groin and drains into the subinguinal group of the inguinal lymph nodes.

Lateral Vessels

The lateral vessels emerge from the lateral surface of the foot and either follow the small saphenous vein into the popliteal nodes or ascend in front of the leg, crossing close to the knee joint to join the medial group.

Deep Lymphatic Vessels

These are far fewer in number than their superficial counterparts and travel alongside the lower leg’s deep arteries. They are divided into three groups: anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and peroneal, which follow the corresponding artery and enter the popliteal lymph nodes.

Lymph nodes

The inguinal nodes

The inguinal nodes are located in the upper aspect of the femoral triangle and range in number from 1 to 20.

They are divided into two groups based on their position to a horizontal line drawn at the level of the great saphenous vein’s termination. The sub-inguinal nodes (which include both deep and superficial sets) are below this line, while the superficial inguinal nodes are above it.

Superficial inguinal nodes.

These form a line immediately beneath the inguinal ligament that receives lymph from the penis, scrotum, perineum, buttock, and abdominal wall.

Superficial Sub-Inguinal Nodes.

These are found on both sides of the proximal part of the great saphenous vein. They obtain afferent input mainly from the lower leg’s superficial lymphatic vessels.

Deep Sub-Inguinal Nodes.

These are usually found in groups of one to three and are located on the medial aspect of the femoral vein. The afferent supply to these nodes comes from the deep lymphatic trunks of the thigh that accompany the femoral vessels.

Popliteal nodes

Popliteal lymphatic nodes are small, ranging from five to seven in number, and are frequently found embedded in stored fat in the popliteal fossa. They get lymph from the lateral superficial vessels.

The efferent blood vessels of the popliteal nodes travel nearly beside the femoral vessels before emptying into the deep inguinal nodes. However, some will follow the great saphenous vein as well as drain into the subinguinal nodes.

Clinical Significance

Iliopsoas tendonitis:

This occurs when the tendons connecting the iliopsoas to the femur become irritated and inflamed. Symptoms of iliopsoas tendonitis include pain in the front of the hip when flexing it, pain when stretching the hip into extension, and difficulty running. Iliopsoas tendonitis is caused by overuse, and muscular imbalance, tightness, and weakness in neighboring muscles may all contribute to the condition.

Iliopsoas bursitis:

Bursitis can develop when the small, fluid-filled sac in the front of the iliopsoas is irritated. This bursa irritation can cause hip pain and make it difficult to flex and extend the hip. When the hip is forcefully contracted, iliopsoas bursitis usually causes no pain. Rather, the pain occurs when the hip is stretched and the iliopsoas muscle presses against the bursa.

Snapping hip syndrome:

Snapping hip syndrome, also known as “dancer’s hip,” is characterized by a popping or snapping sensation in the front of the hip while moving it. It’s usually painless, but having a constant snapping sensation while moving can be annoying. Tightness of the iliopsoas muscle causes the hip to snap and rub against other bony or ligamentous structures in the hip.

Weakness of iliopsoas due to lumbar injury:

If you have lower back problems like herniated discs or lumbar facet arthritis, the femoral nerve may be compressed. This can cause pain in the front of your thigh, and your iliopsoas muscle may weaken and even shrink in size as a result. The muscle weakness caused by lumbar radiculopathy may make it difficult to walk and rise from a supine position normally. If the weakness is severe, immediate attention may be required to relieve pressure on the nerve and restore normal nerve function to the muscle.

Spasm of the iliopsoas:

Iliopsoas spasms are occasionally experienced by people suffering from low back and hip pain. This results in a tight feeling in the front of the hip and makes it difficult to extend the hip backward. Iliopsoas spasms can be caused by repetitive strain and overuse. Spasms of the iliopsoas can also occur as a result of nerve injury caused by a neurological condition such as multiple sclerosis or following a stroke. While many diseases affecting the iliopsoas muscle can cause pain and limited mobility, there may also be other causes of hip pain.

Hip labrum tears:

A hip labrum tear can cause pain in the front of the hip, and femoroacetabular impingement can make flexion and extension painful. Hip arthritis can cause limited mobility in the hip joint. Hip labrum tears can have an impact on the iliopsoas, but not always.

Pectineus muscle strain:

The most common symptoms of a pectineus muscle injury include pain, bruising, swelling, tenderness, and stiffness. Pain in the front hip area could indicate that you have strained the primary hip flexor muscles, the hip adductor muscles, or a combination of the two.

Overstretching can result in a pectineus strain. Pectineous pain can be caused in a variety of ways.

- Changing directions suddenly or quickly.

- Having legs crossed for long periods.

- Fast movements, such as kicking or sprinting.

- Overstretching one or both legs to the side of the body

- Taking too long strides while running or power walking

- Exercising with exertion after the pectineus muscle is already fatigued legs splint/cast, foot/ankle problems, sudden overload due to gymnastics, football/ice skating injury, horse riding, skiing, cross-legged sitting, leg length difference. Persistent “internal” groin pain, groin strain, hip pain, post-hip replacement rehabilitation, post-hip fracture, pregnancy, postpartum, pain during sexual intercourse/hip adduction exercises (gym), and hip osteoarthritis.

The pubis and femur are attached to the medial (or middle) part of the thigh, so straining the groin muscles can cause soreness and pain throughout the inside of the thigh. Soreness from the tendon or muscle at the top or superior end of the muscle will occur at the very top of the inner thigh, near the pubic region. Soreness from the tendon or muscle at the bottom or inferior end of the muscle will extend down the side of the thigh and deeper into it.

Once injured, the pain will be caused by lifting the thigh straight out in front of the body. Pain will be felt as the groin muscles are stretched as the thighs widen outward.

Overstretching, specifically stretching one or more legs out to the side or front of the body, can injure the pectineus muscle. Pectineus injuries can also be caused by rapid movements such as kicking or sprinting, changing directions too quickly while running, or sitting with one leg crossed for an extended period.

Pes anserine bursitis:

Pes anserine bursitis, an inflammatory condition affecting the medial portion of the knee, is one of many conditions that can impair sartorius muscle function. Pain, swelling, and tenderness are common symptoms of this condition, which occurs in athletes due to overuse.

The pes anserinus involves the gracilis, semitendinosus, and sartorius muscles’ tendons, which attach to the anteromedial portion of the proximal tibia. When the bursae underlying the tendons become inflamed, they separate from the tibial head. Bursitis frequently becomes chronic if the inflammation is not addressed and treated properly (rest, cooling, pain medication, and a local corticoid injection if needed).

Anterior Superior Iliac Spine (ASIS) Avulsion:

Young athletes are allowed to have ASIS avulsion injuries through the physis. These injuries are typically caused by indirect trauma, specifically a sudden, forceful contraction of the sartorius muscle and the tensor fascia lata. Ossification of the apophysis usually occurs between the ages of 21 and 25. Before this ossification, there is a weak point at the muscle-tendon-bone interface that allows for an avulsion. This usually occurs when the hip is in an extended position, such as sprinting and swinging a bat.

Avulsions of ASIS are most commonly treated conservatively. This includes rest, stretching, protected weight bearing with crutches, and the early start of a range of motion exercises. There are indications for surgical treatment of this injury. If the piece is displaced, there is a risk of irritation, strength loss, and healing of the part in its displaced position if the injury is treated conservatively.

When the ASIS avulsion displaces more than 2-3 centimeters, open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) is used. Painful non-unions can also indicate the need for surgical fixation. There are several options, including lag screw and tension band fixation.

Avulsion fracture:

The Rectus femoris muscle-tendon can cause a fragment of the hip’s anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) to avulse, resulting in an Avulsion fracture. An avulsion fracture occurs when a muscle contract forcefully, generating a force greater than that required to hold the bone together. It is a popular but uncommon sports injury that can occur in young athletes.

Rectus Femoris Strain:

Rectus femoris muscle strain, also known as hip flexor strain, is an injury at the tendon that connects to the patella or the muscle itself. The injury is usually a partial tear, but it could be a complete tear. The injury is caused by a forceful motion associated with sprinting, jumping, or kicking, and it is common in sports such as football and soccer. The rectus femoris muscle is susceptible to injury because it crosses both the knee and the hip. Symptoms include a sudden sharp pain at the front of the hip or in the groin, swelling and bruising, and an inability to contract the rectus femoris muscle due to a complete tear.

Sartorius muscle strain:

Musculus sartorius is a type of upper leg muscle that originates at the spine iliaca anterior superior on the pelvic bone, travels diagonally down the entire length of the femur, and connects to the proximal medial part of the tibia. It is the longest muscle in the human body, and its primary function is knee flexion. However, it also plays a synergistic role with hip internal rotation. It is commonly called the tailor muscle, because it is active in a position that is very general for this profession, ie. the muscle that results from crossing one leg over the other. the sartorius muscle is active during the movement of crossing the legs & it can also very often lead to problems if this position & movement are perpetuated continuously.

Injury or damage to the sartorius muscle can cause pain and problems in the groin and hip region because it originates in those areas. Sartorius muscle strain can cause difficulties with daily activities like walking, dressing, and sports. A strained sartorius occurs when the anterior upper leg musculature is overly extended during a movement and excessive loads are applied to it, causing the muscles, including the sartorius muscle, to become overstretched. Smaller and larger muscle fiber ruptures can occur when the muscle is strained or overstretched.

Sartorius Muscle Tendonitis:

Tendonitis causes pain in the Sartorius muscle and limits its mobility. You may experience pain in the front of your hip when flexing and rotating it while walking. Therapy may help reduce inflammation and improve the muscle’s ability to contract properly, allowing you to regain mobility.

Sartorius muscle tears:

A sartorius muscle tear may necessitate prolonged immobility and rest to allow the muscle to heal. Once healing has occurred, the physical therapist may work with you to improve scar tissue mobility, sartorius muscle flexibility, and muscle strength.

Risk of tight hip flexors:

Tight hip flexors can cause problems in several areas of the body. Tight hip flexors can accomplish the following:

- Limiting mobility can cause lower back pain

- Abnormal walking

- Decreased speed

- Hip pain

- Increased risk of injury during exercise

- Long-term hip issues.

Stretching exercise for hip flexor muscles:

- Hip Flexor Bed Stretch

- Hips Elevated stretch

- Hip Opener and Groin Stretch

- Table Psoas Stretch

- Kneeling Hip Flexor Stretch

- Standing Hip Flexor Stretch

- Standing Sartorius Stretch

- Butterfly stretch

- Standing Pectineus Stretch

- Kneeling Pectineus stretch

- Half-kneeling Pectineus dips

- Lateral squat

- Crossover stretch

- Seated Pectineus stretch

- Supine Wall Stretch

- Supported Side-Plank Reach

- Knee to chest stretch

- Pigeon Pose

- Standing Stance Pelvioc Tilt

- Wall psoas Stretch

- Sumo Squat Stretch.

- Lunge Stretch

- Standing Lateral Lunge Stretch

- Runner’s Lunge

- Standing Adductor Stretch

- Hip Flexor Bed Stretch:

- How to Perform this Stretch: Lie supine on the bed, with your left leg closest to the edge.

- Slowly lower your left leg to the side of the bed.

- The right leg may remain bent, with the foot on the bed.

- The patient can feel the stretch in his hip flexor.

- Ideally, the foot will hover above the ground rather than touching it. But it’s fine if it touches the ground.

- Deepen the stretch by slowly bending the knees. The individual should feel across the thigh and front of the hip.

- Hold the hanging position for 20 to 30 seconds.

- Return to the left leg of the bed and rotate so that the right side is closest to the edge of the bed.

- Repeat the hip flexor bed stretch 2-3 times on each side.

2. Hip Elevated Stretch:

- To perform the stretching exercise, lie supine with your legs extended in front of you and arms at your sides.

- After that, place the foam roller or block under the hips and lower back.

- So the hips are raised while the head and shoulders rest on the ground.

- Bend the right knee and wrap the arms around the shin, bringing it closer to the chest.

- Stay there for 60 to 120 seconds.

- Then repeat the movement to the opposite side.

3. Hip Opener and Groin Stretch:

- How to stretch: Begin in a forward lunge and lower your right knee to the floor.

- Place your left elbow on the inside of your left knee, as shown.

- Gently press the left side of your elbow into your left knee, then twist your entire body to the right.

- Reach your right arm behind you until you feel a gentle stretch in the lower back and left groin.

- Hold the stretch for 20-30 seconds, then release and repeat with the right leg.

4. Table Psoas Stretch:

- How to stretch: Choose a table that is slightly lower than your hip level.

- Stand with your left side next to the table, lift your left leg behind you, and place it on a table with the knee facing down.

- The leg will be aligned. To relieve pressure from a table, the patient may place a folded towel under their knee.

- Position the palm of your hand on the surface of the table in front of you. Your right leg should be slightly flexed.

- Gently move into the stretch by raising the chest and opening up the hip flexors.

- Pause when you feel a stretch in your left hip.

- Hold the standing position for 20 to 30 sec.

- Let go of the stretch &as well as repeat on the other side.

- Repeat the table psoas stretch three times on each side.

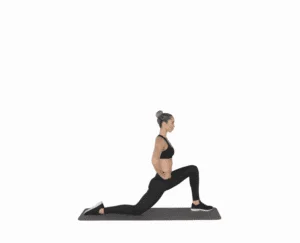

5. Kneeling Hip Flexor stretch:

- Stretching: Begin in a half-kneeling position with the left leg about two feet in front of the right.

- The left knee should form a 90-degree angle. The patient must use the mat for cushioning.

- Maintain an upright posture by resting your hands on your left knee.

- Next, incline slightly forward until you feel a stretch in the front of your right hip, groin, and thigh.

- Keep your knees bent for a duration of 20 to 30 seconds. The individual should not experience any lower back pain. If the patient does, relax the stretch.

- Slowly return to your starting position and change sides.

- Perform the kneeling hip flexor stretch 2-3 times per side.

6. Standing Hip Flexor Stretch:

- This stretch is beneficial for those who are unable to kneel.

- How to Stretch: Stand tall, with your feet about hip distance apart.Step with the left foot forward, forming a split stance.

- Engage the core muscle and tuck the pelvis. The patient may place their hands on the left leg.

- Keep your back leg erect and lunge forward using the left leg.

- The patient may feel a stretch in the front of the hip, groin, and right thigh.

- Hold the lunge position for 20-30 seconds. The individual should not experience any lower back pain. If you do, relax the stretch.

- Perform the standing hip flexor stretch 2-3 times per side.

7. Standing Sartorius Stretch:

- How to do this stretch: Stand on the left leg. To maintain your balance, support yourself against a sturdy piece of equipment.

- Position the right heel close to the buttocks.

- Grasp the right foot with both hands if possible, or in the right hand to keep it close to the body.

- suppose pushing the hips toward without lifting the back. The stretch can be felt in the front of the hips and possibly down the inner side of the thigh.

- Breathe normally. Pause the stretch for 15-30 seconds before gently releasing and repeating on the opposite side.

8. Kneeling Sartorius Stretch:

- How to do this stretch: Kneel with your left knee on the ground and your right knee bent at a 90-degree angle in front of you, your foot flat on the floor. If necessary, support yourself against a wall to maintain balance.

- Maintain an upright spine and imagine the pelvis as a bucket filled with water. Maintaining the pelvis in a neutral position, that is, not tilting forward or backward, will prevent the imaginary water from spilling out.

- Lean forward with your spine completely straight. Think about pushing the pelvis forward while keeping it level.

- Clenching your buttock muscles while performing can help you get a feel for the proper motion.

- Pause the stretch for 10-30 seconds, breathing normally while doing so, then gently release and repeat on the opposite side. Repeat the kneeling stretch 2 to 5 times for each leg.

9. Butterfly Stretch:

- To perform this stretch, sit on the mat with your legs in front of you.

- Reach forward and grab the left foot. It is acceptable to flex the knee to facilitate the hand-foot joint.

- Slowly bend your left foot up towards the groin until it is in a comfortable position with the sole facing the right thigh.

- Flex your right knee and bring your right foot toward your groin, ensuring that its sole touches the sole of your left foot.

- Grab the feet with your hands and rest your elbows on the knees.

- Allow your knees to fall toward the ground while maintaining an upright posture. You can apply pressure to the inner thigh by slowly pressing on the knees with your elbows.

- Hold for 60 seconds once you feel stretched.

- Repeat 3–4 times.

10. Standing Pectineus Stretch:

- How to stretch: Straighten the legs to the side and form a “V” shape.

- To avoid joint strain, don’t overdo this pose.

- Many people find that simply sitting in this position provides an inner thigh stretch.

- If you want to feel more stretched, keep your back straight and lean toward the floor with your hip joints.

- Stay there for about 10 to 15 seconds. Breathe normally.

11. Half-Kneeling Pectineus Stretch:

- How to stretch: Begin in a half-kneeling position, with the right knee on the floor and the left leg bent, foot on the floor.

- Extend your left leg out to the side as much as possible.

- Your foot could be at a right angle to your knee.

- Dip your body toward the left leg, keeping your hands on your hips.

- You can feel the stretch in the inner thigh, particularly on the right side.

- Repeat 8 to 10 times.

12. Frogger Stretch:

- How to stretch: Begin by placing your knees and forearms on the ground, making your knees and feet wider.

- Try to keep the insides of your feet on the ground.

- Sit the buttocks back against the heels, feeling the stretch in the inner thighs.

- Pause for 10-15 seconds before releasing the stretch and returning to the position.

- Repeat 8 to 10 times.

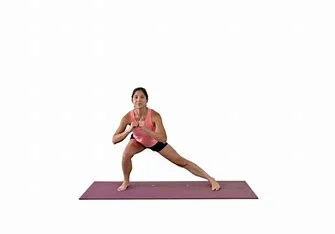

13. Lateral Squat:

- How to stretch: Stand tall and place your feet double shoulder width apart.

- Transfer the weight to your left side leg, bend the knee on that side, and push your hips back like you’re sitting.

- Drop as low as you can while keeping your right leg straight.

- Keep your chest up and your weight on the left leg.

- Breathe and hold for 15-20 seconds before returning to the starting position.

- Repeat 2-3 times, and then get to the opposite side.

14. Crossover Stretch:

If you enjoy dancing, this move may come naturally because it is similar to the “grapevine” dance move.

- How to stretch: Begin with both feet together, then take a step to the right with your right foot.

- Cross your two feet.

- Step to the right again with your right foot, then bring your left foot to join it.

- Repeat on the opposite side after both feet are together.

- You can begin slowly and increase your stride as you become accustomed to the movement.

- Repeat it 5-10 times.

15. Seated Pectineus Stretch:

- How to stretch: Straight the legs out to the side, and make a “V” shape.

- To avoid joint strain, don’t overdo this pose.

- Many people find that simply sitting in this position provides an inner thigh stretch.

- If you want to feel more stretched, keep your back straight and lean toward the floor with your hip joints.

- Stay there for about 10 to 15 seconds. Breathe normally.

16. Supine Wall Stretch:

- How to stretch: In a supine position in front of a wall, one leg elevated.

- Move as close to the wall as possible while maintaining a comfortable hamstring stretch.

- Maintain a straight leg while slowly splitting open until you feel a stretch on the inner side of your legs.

- Hold a stretch for 15–30 seconds.

- Relax and repeat three times.

17. Supported Side-Plank Reach:

Side Planks

- How to stretch: Lie on your back, legs extended on the floor. Slowly bend a single knee toward your chest.

- Keeping your back flat, bring your knee as close to your chest as possible without discomfort.

- Stretch your straight leg as far as possible and squeeze your glutes.

- go back to the position where you started and recite with the opposite leg.

- If you don’t feel any stretch, try doing this stretch on a bench with your lower leg hanging off.

18. Pigeon Pose:

- How to perform this stretch: Start in the plank position.

- Slide your right foot forward, bringing your knee next to your right hand and your foot near your left.

- Your flexibility determines where your knees and toes will drop.

- Slide your left leg as far back as possible while keeping your hips square.

- Lower yourself to the ground and onto your elbows, bringing your torso as low as possible.

- Hold the stretch without allowing your chest to drop.

- When you feel you’ve had a good stretch, switch sides.

19. Standing Stance Pelvic Tilt:

- How to stretch: Stand tall with good posture, chest pointed up, and shoulders back.

- Push the pelvis back and under.

- Hold the standing pose for 10 to 20 seconds.

- Release.

20. Wall Psoas Stretch:

- How to Perform this Stretch: Take a lunge position in front of a wall.

- Rest your right foot against a wall.

- Drive the knee closer to the wall.

- Rotate the hips backward again.

- To reduce the stretch’s intensity, drive the knee forward.

- Hold the psoas stretch for 15-20 seconds and repeat 3-4 times.

21. Sumo Squat Stretch:

- How to Perform this Stretch: Stand tall, feet wider apart.

- Laterally rotate your feet. The knees and toes are pointing out.

- Maintain a straight back and an upward-facing chest.

- Squat down while keeping the thighs facing out.

- Pause the squatting position for 10-15 seconds and repeat it 2-3 times.

22. Lunge Stretch:

- How to stretch: Begin by kneeling on the ground in a lunge position.

- Bend your torso forward, bringing the outside shoulder to the interior of the lead knee.

- Then lunge forward so that your hips slide forward.

- You can feel a stretch on the inside of the forward leg.

- Hold this adductor stretch for 5-10 seconds before releasing.

- Perform 10 to 12 repetitions.

23. Runner’s Lunge:

- How to stretch: Begin by kneeling with both knees on the ground.

- Then, move the left foot forward until the left knee is directly above the left ankle.

- Extend the right leg behind you, keeping the knee behind the hip and the top of the foot on the floor.

- Rest your hands on the left thigh.

- Drive the top of your back foot into the ground to achieve a deeper stretch.

- Pause for 60-120 seconds, then repeat the movement on the other side.

- It is a single repetition. Do it three to four times.

24. Squatting Groin Stretch:

- How to stretch: Stand with your feet wide apart and your toes pointing outward.

- Begin squatting slowly until your knees are directly over your ankles and bent at 90 degrees.

- Place your hands on the tops of the inner thighs as well as gently pull them outward to open your hips.

- You will feel the stretch on the inner side of each leg.

25. Frog Squat With Arm Raise:

- How to stretch: Place the right hand on the ground immediately following the first stretch.

- Continue to gradually push your inner thigh outward as you raise your left hand directly to the roof, fingers pointing upward.

- Twist your upper body slightly with each breath, reaching as high as possible.

- Your right heel may lift slightly.

- Then switch to the other side.

27. Standing Adductor Stretch:

- How to stretch: Start standing with your feet about 3 feet apart.

- Transfer your weight to one side and bend your knees.

- Keep your other knee straight to experience a stretch on the inner side of your thigh.

- Take the stretch for 15–30 seconds.

- Relax and repeat on the opposite side.

Health advantages of stretching the hip flexor muscle:

If a patient stretches properly, they can gain many benefits, including:

- A good quad stretch stimulates the muscles and increases blood flow to the area.

- This also reduces rectus femoris muscle tension and pain.

- A good stretch will prepare the muscle for a variety of physical activities, including running, brisk walking, squats, yoga, and other sports activities.

- Rectus femoris stretching exercises improve short-term range of motion, including hip flexion and knee extension.

- This stretch helps you avoid injuries while doing leg workouts.

- This increases long-term flexibility and mobility.

- This alleviates muscle soreness.

Some common mistakes that patients should avoid when stretching their hip flexor muscles

The patient cannot make the following mistakes while stretching:

- Bouncing: Do not bounce while stretching. If the patient finds himself doing so, you should stabilize yourself by holding onto solid objects.

- Locking the Knee: Never lock your standing knee while stretching. Keep it soft.

- Knee Moving Outward: Do not let the bent knee drift outward. Maintain both knees next to one another.

- Stretching before Warm-up: To avoid muscle strain, the patient should only stretch after you have completed the warm-up.

- Stretching to Pain: Stretch until you experience mild discomfort, but do not stretch to the point of pain. Take precautions not to strain your knee. The goal is not to touch the heel to the buttock but to feel the gradual stretch in the thigh.

- Arching the Back: Do not arch the lower back as you bend the knee; instead, keep the abdominals engaged to keep the back neutral as you drag into this stretch.

Stretching Safety Guidelines For Hip Flexor Muscle:

There are certain guidelines the patient must follow while stretching:

- Stretching is not an exception. Stretching can be dangerous and cause injury if performed incorrectly.

- Breathe: Never hold your breath. Holding your breath causes tension and stress in your muscles, which may raise your blood pressure. The deeper you breathe, the more relaxed your muscles will be, allowing you to stretch deeper and for longer.

- Stretching tight muscles is uncomfortable for you, but the patient should never experience stabbing or sharp pain.

Be consistent: Stretch for a few minutes or seconds a couple of times per day to gradually increase flexibility and range of motion over time. It is a better way to stretch than doing it longer and only once a week.

Wear loose, comfortable clothing; it is difficult to stretch if your clothes are tight and restrict movement.

Strengthening Exercise for Hip flexor muscle

- Lunge

- Floor-sliding mountain climbers

- Straight leg raise

- Psoas hold

- Standing Knee Raise

- Barbell Rollout

- Dumbbell Stepup

- Psoas March

- Dumbbell Bulgarian Split Squat

- Alternating Straight Leg Raise

- Back-Supported Leg Raise

- Half Kneeling Lift-off

- Glute bridge

- Standing Leg Circles

- Hips Elevated

- Hip raises

- Leg raises

- Clam Exercise

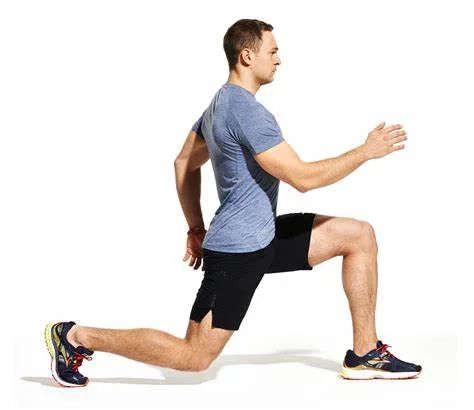

Lunge:

Lunges target the lead glute and quad muscles, including the rectus femoris (a hip flexor). They also stretch the hip flexors in the back leg, which must lengthen based on how far you step forward.

Take a large step toward your right foot from where you are standing. Maintain your trunk upright throughout the movement.

Bend your extended knee and move your weight to your right leg. Continue to slowly lower yourself into the lunge until your left knee is just above, or gently touches, the floor. Your right knee should sit directly above your right ankle.

Step back to a standing position.

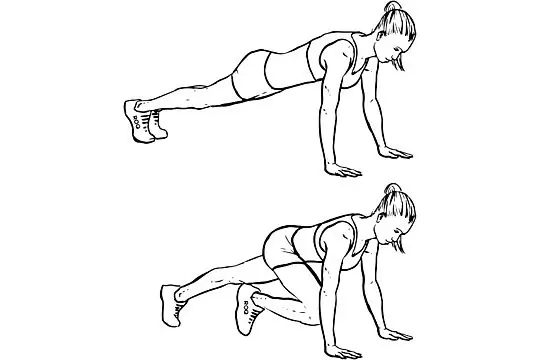

Floor-sliding mountain climbers:

Grab a few sliding discs, paper plates, or hand towels—anything that slides. Get ready to climb!

- Place yourself on a hardwood floor or another smooth surface.

- While doing pushups, place the sliders under the balls of your feet.

- Pull your right leg toward your chest, then alternate with your left leg, just like a standard mountain climber.

- Start slowly and gradually increase your speed.

Straight leg Raise

This exercise targets the iliopsoas and rectus femoris. The abdominal muscles contract to stabilize the trunk as the leg lifts.

- Lie on your back, one knee bent. Extend the opposite leg while keeping the knee straight.

- Tighten your abdominals as you lift the leg, bringing the thigh in line with the opposite bent knee.

- Hold for two counts before slowly lowering to the starting position. Repeat.

Psoas hold:

This move strengthens the psoas, a deep hip flexor muscle that can lengthen strides and reduce injury. A win-win scenario!

- From a standing position, bend your right knee and raise your upper leg to the sky.

- For about 30 seconds, balance on your left foot with your right knee and thigh at hip level.

- Lower your right leg gradually, then repeat with your left.

- Remember to keep your trunk tall throughout the movement. If your head bobs forward or your trunk rounds, don’t raise your leg as high.

Standing Knee Raise:

Last but not least, the standing knee raise. Although the standing knee raise is difficult to load, it is one of the most effective exercises for targeting the hip flexors directly. Consider it a slow-motion, standing-in-place march.

How to Perform the Standing Knee Raise:

- Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart.

- Raise one knee until your thigh is perpendicular to the ground.

- Pause, and then come back to the position from which you started.

- Repeat with the opposite leg.

- Wear ankle weights or insert your foot into the top part of a kettlebell to load the exercise.

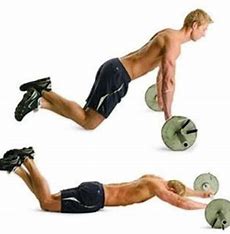

Barbell Rollout:

The barbell rollout as well as the ab wheel are underutilized and overlooked, but there is no denying their brutal effectiveness.

If your gym is without an ab wheel, you can purchase one online for a low cost. It’s of value the investment to keep one in your workout bag. You can also use a barbell with 10-kilogram plates on each side to roll out.

How to do the Barbell Rollout:

- Kneel with your knees about hip-width apart, and grasp the ab roller with both hands. The ab roller should be located on the floor in front of you.

- Gradually roll the ab roller or barbell onward, stretching your body to a straight position. Similar to participating in the plank, check that the movement does not originate from your spine or hips. Keep a neutral spine all through the set.

- Go as low as possible, with only the bottoms of your feet and knees touching the floor.

- After a pause at the end of the range of motion, begin pulling again with your abdominal muscles to the position from which you started. Maintain your abs tightly at all times.

Dumbbell Stepup:

The dumbbell step-up is an excellent lower-body exercise to incorporate into your leg workouts because it builds muscle, strength, and balance. Use a box or bench that is 12 to 18 inches (30-46 cm) tall or high enough to create a 90-degree angle at the knee joint when the foot is on the box.

How to Perform the Dumbbell Step-Up:

- Hold the dumbbells at your sides, approximately 12 inches away from a box or bench. Step up one leg, placing your entire foot on the box.

- As you step up onto the box, keep your torso erect and avoid leaning forward. Push off with your lead leg already on the box, then bring your back foot onto it.

- Once both feet are on the box and your legs are straight, return both feet to the ground one at a time.

- Repeat with the other leg.

Psoas March:

Once both feet are on the box and your legs are straight, return both feet to the ground one at a time.

Repeat with the other

Dumbbells Bulgarian Split Squat:

The dumbbell Bulgarian Split Squat (BSS) constitutes a single-leg exercise that targets the lower body. One of the most significant advantages of this movement is its safety. If someone has a lower back injury or another limitation, they can use the BSS instead of the back squat.

How To Perform Dumbbell Bulgarian Split Squats:

Dumbbells-Bulgarian-Split-Squat

- Hold a dumbbell at the sides while standing directly in front of a bench.

- Reach one leg behind you and place the top of your foot flat on the bench.

- Brace your core and descend with control until your back knee is a few inches off the ground or your front thigh is parallel to the floor.

- To return to the top position, fully extend your knees and hips. Ensure that your torso remains upright throughout the rep.

Alternating Straight Leg Raise:

The straight leg raise increases hip mobility, stability, and strength. It is one of the most commonly used exercises in physical therapy for hip and knee injuries. However, it is also an excellent exercise for maintaining healthy hips and increasing hip mobility.

How to Perform the Alternating Leg Raise:

Start by lying on the floor with your legs standing in front of you, and arms at the sides.

Squeeze the quad in your left leg and lift it to 45 degrees while keeping your left knee as well as your leg straight. Hold for as long as five seconds before returning to the surface in a controlled motion. Keep your right leg straight and parallel to the ground the entire time.

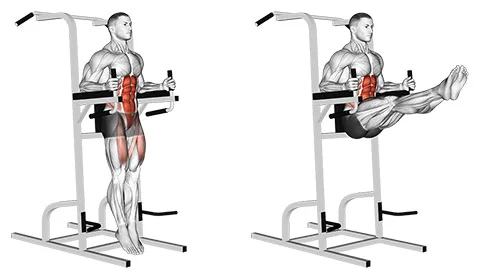

Back-Supported Leg Raise:

The back-supported leg raise, also known as the Roman Chair or Power Tower, is one of the best overall ab exercises. The movement focuses on the lower section of the abdominals but also includes the hip flexors.

How to Perform Back-Supported Leg Raises

- Support your body by placing your elbows on the pads. Align your back with the back support.

- Begin the movement by raising your legs to 90 degrees in front of you and rounding your lower back to contract the abdominal core. The key is to lift your legs high enough.

- Once your legs are horizontal, controlably lower them down. Make sure your feet are extended down between reps.

Half Kneeling Lift-off:

Half-kneeling exercises, like this lift-off move, focus on the end range of hip flexion, which is where most people struggle, according to Cook.

- Begin in a half-kneeling position on the floor facing a wall, with the right knee bent at a 90-degree angle and resting on the ground directly beneath the right hip. The left knee is bent at 90 degrees in line with the left hip, and the left foot is flat on the ground. Set both hands on the surface at shoulder height.

- Draw the shoulders down and back, and engage the core. Keeping the left foot flexed, drive the left knee up toward the chest, lifting it as far as mobility allows.

- Hold for 5-10 seconds. Then, with control, slowly lower the left foot to the floor.

Glute bridge:

- You’re lying on your back, arms at your sides, knees bent, and feet flat on the floor.

- Then, engage your glute muscles and lift your hip joint to form a bridge between your shoulders and knees.

- Raise your hips so you can feel a stretch to your iliopsoas muscles in both legs.

- When you have lower back pain, lower your hip joint slightly but keep your glute muscles tight.

- Hold this stretching position for 20-30 seconds.

- Then, slowly return to the starting position.

- Perform this exercise ten times in a single session and three times per day.

Standing Leg Circles:

- This is a dynamic warm-up exercise that increases blood circulation to the hip muscle and upper leg.

- For the standing leg circle exercise, stand with your feet hip-width apart.

- Raise the left leg off the ground. While balancing on your right leg, draw a small circle with your left.

- Repeat 10 to 20 times on the left side, then switch to the right leg.

- Note: If you have a balance problem, stand close to a prop that will help you maintain your body by holding onto something.

Hips elevated:

- You’re lying on your back, legs straight in front of you and arms at your sides.

- Then, place a foam roller and a block under your hip joint and lower back to elevate it.

- Keep your shoulder joint and head resting on the ground.

- Then bend your left knee and wrap your arms around your shin, bringing it close to your chest.

- Hold this exercise for 10 seconds.

- Then slowly return to where you started as well as repeat on the reverse side.

- Perform this exercise ten times in a single session and three times per day.

Hip Raises:

- You’re lying on the ground, both feet planted on the floor near your buttocks.

- Then try to raise your leg straight up while keeping your thighs parallel.

- Raise the hip joint from the ground.

- Hold this exercise position for ten seconds.

- Perform this exercise ten times in a single session and three times per day.

Leg raises:

- Place your both hands and both knees on the floor.

- Hold this exercise position for ten seconds.

- Perform this exercise ten times in a single session and three times per day.

Clam Exercise:

- The patient is lying on the affected side, with the bottom arm extended upward to support the head and neck.

- Flex the hip and knee joints so that the thighs are at a 90-degree angle to the torso, and the knees are also bent at approximately 90 degrees.

- Make sure the shoulder, hip, and knee joints are stacked, and the body is perpendicular to the floor.

- Maintain contact between the big toes, tighten the core muscle, and externally rotate the hip and knee joints open, as if the clam were opening up.

- Rotate as far as you can comfortably with good form, then reverse the exercise movement by internally rotating the hip joint back to the starting position.

- Perform this exercise 10 times before repeating it on the opposite side.

FAQs

What is the strongest hip flexor muscle?

The Iliopsoas muscle

The iliopsoas muscle is the hip joint’s strongest flexor. The psoas major and iliacus muscles contract simultaneously, resulting in a powerful flexion of the thigh at the hip joint.

What is the Sartorius muscle?

The longest muscle in the body, spanning the hip and knee joints, is the sartorius. The term sartorius is derived from the Latin word sartor, which means patcher or tailor and refers to how the individual positions their leg while working.

What are the three hip flexor muscles?

The hip flexors help to balance the posterior pelvic muscles. Daily activities frequently cause three key muscles to tighten and shorten. These include the iliacus, psoas major, and rectus femoris.

Are squats good for hip flexors?

Squats work the leg muscles while also engaging the core. Squats have the added benefit of being extremely flexible, allowing a person to adjust the intensity to meet their changing fitness needs.

How do you strengthen your hip flexors?

Hip Flexor Exercises for Strength and Stretch

How to strengthen your hip flexors (and the surrounding muscles)

Lunge. Lunges target the lead glute and quad muscles (including the rectus femoris, a hip flexor).

Mountain climbers sliding on the floor.

Straight-leg raises and Psoas hold.

etc…

REFERENCES

- Hip Flexors. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Hip_Flexors