Hamstring Muscles

Introduction

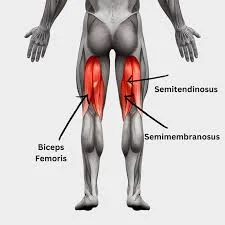

The hamstring is a group of 3 muscles located at the back of the thigh. These muscles include the biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus. Together, they play a crucial role in various movements of the hip and knee, such as walking, running, and jumping.

The hamstrings are a group of three muscles that primarily help to flex the knee. The hamstrings consist of three muscles:

- Semitendinosus

- Semimembranosus

- Biceps Femoris

The muscles connect two joints and have long proximal and distal tendons, resulting in long muscle-tendon junctions (MTJ). MTJs extend into muscle bellies, overlap, and allow forces to be transmitted and dissipated as muscles contract and relax.

The hamstrings are a group of muscles located in the thigh’s posterior compartment. They work together to extend at the hips and flex at the knee.

The sciatic nerve (L4-S3) innervates these muscles, and the inferior gluteal artery and perforating branches of the deep femoral artery supply them with blood vessels.

The hamstring muscles are prone to injury, particularly in athletes who run and sprint. These muscles are put under a lot of strain when you suddenly stop, slow down, or change direction. Extending your leg while running can also overstretch these muscles. It’s common to refer to a hamstring injury as a “pulled hamstring.”

Anatomy of hamstring muscles

The muscles in the thigh’s posterior compartment are the biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus.

The hamstring portion of the adductor magnus functions similarly to these muscles but is located in the medial thigh.

Biceps Femoris.

The biceps femoris has two heads (long and short) and is the most lateral muscle in the posterior thigh. The common tendon of the two heads can be palpated laterally in the popliteal fossa (posterior knee region).

- Origin:

The long head develops from the superior medial quadrant of the posterior surface of the ischial tuberosity.

The femur’s middle third linea aspect, lateral supracondylar ridge, is where the short head originates. - Insertion:

It inserts into the fibular head and extends to the lateral collateral ligament and lateral tibial condyle. - The main action is flexion of the knee. It also extends the thigh at the hip and rotates laterally at the hip and knee joints.

- Innervation: The tibial part of the sciatic nerve innervates the long head, while the common fibular part innervates the short head.

Semitendinosus

The semitendinosus muscle is primarily made up of tendons. It is located on the medial aspect of the posterior thigh, superficial to the semimembranosus.

- Origin: It is derived from the superior medial quadrant and posterior surface of the ischial tuberosity.

- Insertion: It inserts into the superior and medial tibial shafts.

- Leg flexion at the knee joint is the action. Thigh extension at the hip joint. At the hip joint, the thigh rotates medially, as does the leg at the knee joint.

- The sciatic nerve innervates the tibia.

Semimembranosus

The semimembranosus muscle is flat and broad. It is situated deep to the semitendinosus on the medial aspect of the posterior thigh.

- Origins: It originates from the superior lateral quadrant of the posterior surface ischial tuberosity.

- Insertion: It attaches to the posterior surface of the medial tibial condyle.

- Leg flexion at the knee joint is one of the actions. Thigh extension at the hip joint. At the hip joint, the thigh rotates medially, as does the leg at the knee joint.

- The sciatic nerve innervates the tibia.

Embryology

A significant portion of lower extremity development takes place between weeks 4 and 8 of embryogenesis. The embryonic mesoderm gives rise to all skeletal muscle tissue, including the hamstrings. The initial limb bud develops from the lateral plate mesoderm.

Mesodermal cells migrate from the somites in the early embryonic phase and differentiate into myoblasts, which replicate and coalesce to form functional muscle tissue. This is due to a complex array of physiological signals that govern the subsequent organisation and symmetry of the structures formed, including fibroblast growth factors, sonic hedgehog, and Wnt7a.

Anatomical variations

Surgeons must be aware of anatomical variations in the hamstring muscle, even if they are rare. Except for the small head of the biceps femoris, the hamstring muscle group is typically formed by a joint muscular tendon that originates from the ischial tuberosity.

It’s worth noting that some accounts describe variations in which the long head of the biceps femoris and the semitendinosus appear to have distinct tendinous origins. A third head of the biceps femoris and an abnormal muscle inserted into the semimembranosus were discovered, according to a 2013 report.

A patient with a bilateral lack of semimembranosus muscles has also been documented. This discovery was made by chance during an MRI after the patient complained about knee pain after a fall. Given that hamstring autografts are a popular option for ACL restoration, this finding may be relevant in the context of ACL repair, even though the study did not specify whether or not the patient had experienced symptoms as a result of this unusual finding before his presentation.

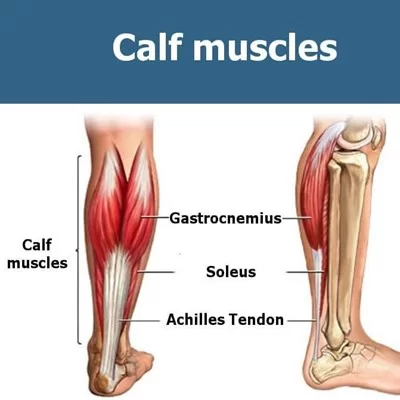

Common peroneal nerve entrapment neuropathy most commonly affects the fibular head and neck. A 2018 study discovered that variations in the short head of the biceps femoris are associated with common peroneal neuropathy. The gastrocnemius and the short head of the biceps femoris were separated by a 4.4 cm tunnel containing the common peroneal nerve.

Function of the Hamstring Muscle Complex

The hamstrings are muscles that extend the hips and flex the knees. The hamstrings play an important role in the complex gait cycle of walking, which includes kinetic energy absorption and knee and hip joint protection. During the swing phase of walking, the hamstrings slow the forward motion of the tibia. The contraction of the hamstring and the contraction of the quadriceps, the hamstring’s antagonist muscle, interact in a complex way.

Blood Supply

The vascular supply to the hamstring muscle complex comes from the perforating branches of the deep femoral artery, also known as the profunda femoris. A branch of the femoral artery is the profunda femoris artery. The inguinal ligament separates the external iliac and femoral arteries.

In general, the thigh’s deep veins are named after the major arteries they follow. The femoral vein is responsible for the majority of the thigh’s venous drainage. It travels alongside the femoral artery and receives additional venous drainage from the profunda femoris vein. The femoral vein, like the femoral artery, joins the external iliac vein near the inguinal ligament.

Common injuries of hamstring muscles

Hamstring muscle injuries are common among athletes who run at high speeds. This includes sprinters, as well as soccer, basketball, and football players. They can also occur in skiers, skaters, dancers, and other athletes who frequently bend their knees in deep squat positions.

You can also get hamstring muscle injuries if you:

- Are a young athlete who is still developing.

- Are over the age of 40.

- Have previously suffered a hamstring injury.

- I have hamstring muscle fatigue.

- Have weak or tight hamstrings or quadriceps (the muscles in the front of your thighs).

- Do not warm up and stretch properly before starting an activity.

Hamstring strains

A hamstring strain is a pull or tear in the muscle fibres. Muscle overload is the most common cause of strain. A strain can affect the tissue in the muscle’s belly or where it connects to the tendons.

A hamstring muscle strain is caused by overstretched muscle fibres. Hamstring strains can vary from mild to severe.

- Grade 1: The muscles overstretch but do not tear. You may experience mild hamstring muscle pain or swelling, but you can usually continue to use your leg.

- Grade 2: One or more hamstring muscles are partially torn. You may be unable to use your leg due to pain or swelling.

- Grade 3: Muscle tissue tears completely away from the tendon or bone. The tendon can even pull a piece of bone away (avulsion). The swelling and pain are severe, and you may have difficulty moving your leg.

Risk Factors

Several factors can increase the likelihood of having a muscle strain, including:

- Muscle tightness. Tight muscles are susceptible to strain. Athletes should maintain a year-round stretching routine.

- Muscle imbalance. A strain may arise from an imbalance where one muscle group is noticeably stronger than the other. This is frequently seen with the hamstring muscles. The quadriceps muscles in the front of the thigh are usually stronger. The hamstrings may tyre out during high-speed exercises more quickly than the quadriceps. This fatigue can result in a strain.

- Poor conditioning. If your muscles are weak, they are less able to withstand the stress of exercise and are more prone to injury.

- Muscle fatigue. Fatigue reduces muscle’s energy-absorbing capabilities, making them more vulnerable to injury.

Choice of activity. A hamstring strain can affect anyone, but those who are particularly vulnerable include:

- Athletes who play sports such as football, soccer and basketball

- Runners or Sprinters

- Dancers

- Older athletes whose exercise programme primarily involves walking

- Adolescent athletes are still growing.

Hamstring strains are more common in adolescents because bones and muscles do not develop at the same rate. A child’s bones may grow more quickly than their muscles during a growth spurt. The growing bone causes the muscle to tighten. A sudden jump, stretch, or impact can tear the muscle’s connection to the bone.

Symptoms of a hamstring muscle injury

Hamstring muscle injuries may result in:

- Hamstring muscle pain is a common issue, often resulting from strains or tears in the muscles located at the back of the thigh.

- An unusual lump or indentation behind the thigh.

- Discoloration or bruises on the rear leg.

- Burning or stinging behind the thigh, also known as gluteal sciatica.

- Difficulty supporting weight on your leg.

- The hamstring muscles are weak.

- The inability to bend your knee may result in walking with a stiff, straight leg.

- A popping sensation on the back of the thigh.

- a sharp, unexpected pain in your thigh’s back.

- Swelling immediately after the injury.

Examination

Patient History and Physical Exam

- People with hamstring strains frequently seek medical attention after experiencing a sudden pain in the back of their thighs while exercising.

- During the physical exam, your doctor will inquire about the injury and examine your thigh for tenderness or bruising. He or she will palpate, or press, the back of your thigh to determine whether there is pain, weakness, swelling, or a more serious muscle injury.

Imaging tests

The following imaging tests can help your doctor confirm your diagnosis:

- X-rays. An X-ray can help your doctor determine whether you have a hamstring tendon avulsion. This occurs when an injured tendon pulls away a small piece of bone.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This research can produce more accurate images of soft tissues such as the hamstring muscles. It can help your doctor assess the severity of your injury.

Treatment

The kind of injury, its severity, as well as your requirements and expectations, will all influence the course of treatment for hamstring strains.

The goal of any treatment, whether nonsurgical or surgical, is to allow you to return to all of your favourite activities. Following your doctor’s treatment plan will help you recover faster and prevent future problems.

Nonsurgical Treatment.

The majority of hamstring strains heal quickly and without surgery.

RICE. The RICE protocol is effective for the majority of sports-related injuries.

- Rest. Take a break from the activity that has caused the strain. Your doctor may advise you to use crutches to avoid putting weight on your leg.

- Ice. Use cold packs for 20-minute intervals several times per day.

- Compression. Wear an elastic compression bandage to help prevent swelling and blood loss.

- Elevation. Recline and elevate your leg above your heart while resting to reduce swelling.

Immobilisation. Your doctor may advise you to wear a knee splint for a short time. This will keep your leg in a neutral position while it heals.

Physical therapy. Physical therapy can start after the initial period of pain and swelling has passed. Specific exercises can help restore range of motion and strength.

A therapy programme prioritises flexibility. Gentle stretches will help you improve your range of motion. As your recovery progresses, you will gradually incorporate strengthening exercises into your routine. Your doctor will advise you on when it is safe to return to sports activity.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is most commonly used for tendon avulsion injuries, in which the tendon has completely separated from the bone. Tears from the pelvis (proximal tendon avulsions) occur more frequently than tears from the shinbone.

Tears in the muscle belly are rarely repaired surgically.

Procedure. To repair a tendon avulsion, your surgeon will pull the hamstring tendon back into place and remove any scar tissue. The tendon is then reattached to the bone with small devices known as anchors.

Rehabilitation. To protect the repair, you must keep your leg elevated after surgery. In addition to crutches, you may need a brace to keep your hamstring relaxed. The length of time you will need these aids will be determined by the nature of your injury.

The physical therapy programme will begin with gentle stretches to increase flexibility and range of motion. Strengthening exercises will be gradually introduced into your plan.

Due to the severity of the injury, rehabilitation for proximal hamstring reattachment usually takes at least 6 months. Distal hamstring reattachments require about three months of rehabilitation before returning to athletic activities. You can find out when it’s safe to resume sports from your doctor.

Hamstring Strengthening Exercises

Stair climbing and descending, walking, and running are activities that enhance the function of the hamstring muscles. Hamstring exercises can benefit anyone, but they are especially beneficial for people who run or cycle, both of which use the quadriceps. Quadriceps development must be balanced with cross-training that includes adequate hamstring strength and conditioning.

Various isolation and compound hamstring exercises can also be used in rehabilitation or bodybuilding. Knee flexion and hip extension exercises are commonly used to strengthen the hamstrings.7 Here are some fundamental moves to practice.

- Basic bridges: This simple exercise isolates and strengthens the hamstrings and gluteus muscles. Press your feet into the floor and contract your glutes to activate your hamstrings and lift your hips.

- Single-leg bridges, like basic bridges, target the hamstrings and glutes while also incorporating leg lifts to promote core stability. Maintain hip and pelvic lift by activating your glutes and hamstrings rather than your back muscles.

- Leg curls: Also known as hamstring curls, these exercises are commonly performed with gym equipment to strengthen the hamstrings and calves. They can also be done with an exercise ball: lie on your back, place your heels on the ball, and then roll the ball in towards you while bending your knees and lifting your hips.

- Squats: This classic exercise can be done with or without weights to strengthen the hamstrings, glutes, and quadriceps. As you lower yourself into a squat, keep your back straight and your head upright.

- Walking lunges: This stability exercise works the hamstrings, quadriceps, glutes, calves, and core muscles while challenging your balance. As you take forward and backward steps, keep your torso upright.

Basic stretches for the hamstring

Hamstring flexibility is important for runners because it can help prevent injury and delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) following exercise.8 Tight hamstrings may limit your ability to straighten your knee. You may also feel a cramp at the back of your knee.

Hamstring stretches can be worked into almost any regular stretching and flexibility routine. The hamstring stretches listed below can be done daily to improve flexibility, promote recovery, and prevent injury.

Seated Stretch

- Sit on an exercise mat with both legs extended in front of you, and feel your sitting bones make contact with the floor.

- Bend one knee and slide your foot in towards the opposite knee, flat on the floor.

- Hinge at your hips and bring your hands to the toes of the straightened leg. If the knee is very tight, you can bend it slightly.

- Stretch for a duration of 15 to 30 seconds.

- Switch sides.

Supine Stretch

- Lie on your back on an exercise mat, knees bent, feet about hip-distance apart.

- Lift one leg towards the ceiling while keeping the spine neutral.

- Reach behind the back of the thigh and gently pull the leg closer. Optional: Allowing the knee to bend slightly will increase the range of motion.

- Hold for 15–30 seconds.

- Lower the leg, then switch sides.

Standing Stretch

- Begin standing tall and upright, with your feet about hip distance apart.

- Take a natural step forward with your heel, keeping your toes lifted.

- Place your hands on your hips and sit back slightly, then hinge forward.

- Allow your spine to naturally round forward as you reach for the elevated toes.

- Allow your knees to soften as you move your seat back a little more and lower your chin to your chest.

- Hold for 15–30 seconds.

- Return your hands to your hips to stand up, and step your feet back together. Switch sides.

Summary

Hamstrings are voluntary skeletal muscles in the back of the thigh that help to flex the knee and are used in various leg exercises. They consist of three muscles: Semitendinosus, Semitendinosus, and Biceps Femoris. These muscles work together to extend at the hips and flex at the knee and are innervated by the sciatic nerve. Hamstring injuries are common among athletes who run at high speeds, such as sprinters, soccer, basketball, and football players. They can also occur in skiers, skaters, dancers, and other athletes who frequently bend their knees in deep squat positions.

Hamstring strains are caused by muscle overload and can range from mild to severe. Risk factors for hamstring strains include muscle tightness, muscle imbalance, poor conditioning, muscle fatigue, and choice of activity. Hamstring strains are more common in athletes who play sports such as football, soccer, basketball, runners, dancers, older athletes, and adolescents.

Hamstring muscle injuries can cause unusual lumps, bruises, burning, difficulty supporting weight, weak hamstring muscles, and difficulty bending the knee. Treatment options include non-invasive therapies like Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation (RICE), immobilization, and physical therapy.

Hamstring strengthening exercises, such as stair climbing, walking, and running, can enhance the function of the hamstring muscles. These exercises are especially beneficial for runners and cyclists, as they use the quadriceps. Hamstring flexibility is crucial for runners, as tight hamstrings may limit the ability to straighten the knee and cause cramps. Hamstring stretches can be done daily to improve flexibility, promote recovery, and prevent injury.

FAQs

What are the hamstrings used for?

The hamstrings are muscles that extend the hips and flex the knees. The hamstrings play an important role in the complex gait cycle of walking, which includes kinetic energy absorption and knee and hip joint protection.

Why are hamstrings the most important?

The hamstring muscles facilitate knee bending, leg extension, walking, and running. However, these muscles are very prone to injury, particularly if you play football or soccer, or engage in other activities that require frequent stops and starts.

Why are the hamstrings so weak?

There are several reasons why hamstring weakness is so prevalent. First and foremost, the hamstrings are a small muscle group that is easily overlooked when it comes to strength training. Many athletes prioritise larger muscle groups, such as the quadriceps and glutes, over the hamstrings.

What is the most common hamstring strain?

Hamstring injuries are common in people who participate in sports that involve sprinting with sudden stops and starts. Soccer, basketball, football, and tennis are some examples. Hamstring injuries can affect both runners and dancers.

What is the blood supply to the hamstrings?

These muscles are innervated by the sciatic nerve (L4-S3) and receive arterial supply from the inferior gluteal artery and perforating branches of the deep femoral artery.

How many muscles make up a hamstring?

The hamstring muscle complex, which consists of three individual muscles, is located in the thigh’s posterior compartment. Together, they play an important role in human activities ranging from standing to explosive actions like sprinting and jumping.

What are the symptoms of a hamstring strain?

Other symptoms of a hamstring strain include sudden and severe pain during exercise, as well as a snapping or popping sensation.

Walking, straightening one’s leg, or bending over can cause pain in the back of the thigh and lower buttocks.

Tenderness.

Bruising.

References:

- Hamstring Muscle Injuries – OrthoInfo – AAOS. (n.d.). https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases–conditions/hamstring-muscle-injuries/

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Hamstring Muscles. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21904-hamstring-muscles

- Hamstrings. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Hamstrings

- Muscles of the Posterior Thigh – Hamstrings – Damage – TeachMeAnatomy. (2024, February 11). TeachMeAnatomy. https://teachmeanatomy.info/lower-limb/muscles/thigh/hamstrings/

- Cpt, A. A. (2024, January 23). Hamstring Muscles: Anatomy, Function, and Common Injuries. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/hamstring-muscles-296481

- Hecht, M. (2019, August 27). Hamstring Muscles Anatomy, Injuries, and Training. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/hamstring-muscles-anatomy-injury-and-training#the-3-muscles

- Rogers, P. (2021, April 13). Hamstring Muscles: Anatomy, Injuries, and Exercises. Verywell Fit. https://www.verywellfit.com/hamstring-muscle-anatomy-and-stretches-3498372

66 Comments