Cervical Spondylosis

What is a Cervical Spondylosis?

Cervical spondylosis refers to age-related wear and tear affecting the spinal disks (vertebrae cushions) in the neck. It leads to disk degeneration and compression of the nerves exiting the spinal canal.

Some key points about cervical spondylosis:

- It typically develops in people over age 40 due to normal aging and repetitive stresses to the neck over time. But injuries can also cause it to happen to younger people.

- As the cervical disks degenerate and lose height, bone spurs or osteophytes often form around the vertebrae to compensate, which can narrow the space for nerves.

- Common symptoms include neck pain and stiffness that radiates to the shoulders or arms. Numbness, tingling, or weakness in the limbs may also occur if nerves become compressed.

- Major risk factors are aging genetics and cumulative impacts from occupational or sports-related neck strain over many years. Poor posture also plays a role.

- Treatments focus on relieving pain and improving function. They can include medications, physiotherapy, exercise, neck braces, traction devices, and sometimes surgery for severe cases with nerve compression. Maintaining good neck flexibility and posture may help prevent progression.

In summary, cervical spondylosis involves progressive degenerative changes and compression in the cervical spine and nerves due to everyday wear and tear as we age. Managing symptoms, movement, and posture are key to living with this common disorder.

Related Anatomy

Types of Vertebrae

The cervical spine consists of 7 vertebrae, labeled C1 to C7 from top to bottom. These include:

- C1: The atlas helps support the skull and allows side-to-side motion.

- C2: The axis allows rotation of the head and has the dens protrusion for pivoting.

- C3-C6: The typical cervical vertebrae allow flexibility while supporting the neck.

- C7: The vertebra prominens connects the cervical and thoracic spine.

Structure of Typical Vertebrae

The vertebrae have several important structural components:

- Vertebral Body: The weight-bearing anterior portion that stacks to form columns.

- Vertebral Arch: The ring that surrounds the spinal cord, formed by pedicles and laminae.

- Spinous Process: The posterior bony protrusions projecting from the laminae.

- Transverse Processes: Lateral protrusions that serve as muscle and ligament attachment points.

- Facet Joints: Connect and allow articulation between the vertebral arches.

- Intervertebral Discs: The flexible cushions between vertebral bodies that allow movement.

Ligaments

Ligaments provide stability and limit excess motion:

- Longitudinal Ligaments – Run along the anterior and posterior sides of the vertebral bodies.

- The ligamentum vivum joins the lamina of neighboring vertebrae

- The ligamentous processes join the spinous processes

- The capsular ligaments encircle the facet joints

Nerves

The cervical nerves exit from the spinal cord through the vertebral foramen formed by the vertebrae:

- Nerve roots exit above correspondingly numbered vertebrae.

- Nerves control muscles, sensations, and reflexes of the neck, shoulders, arms, and diaphragm.

- Compression can cause pain, numbness, tingling, and muscle weakness.

So in summary, the cervical spine has a highly specialized anatomy to support flexibility and mobility while protecting the spinal cord and nerves. Degeneration of these structures underlies common disorders like cervical spondylosis.

Muscles Attached to the cervical spine

Posterior Muscles:

- Semispinalis capitis and services: Extend the head and neck

- Splenius capitis and services: Extend the head and neck sideways

- Erector spinae: Runs full length of spine for extension

- Multifidus: Stabilizes vertebrae for rotation and flexion

- Levator scapulae: Elevates the scapula

Lateral Muscles:

- Scalenes: Flex neck to the side, elevate ribs

- Sternocleidomastoid: Turn and flex the neck

Anterior Muscles:

- Longus colli: Flexes the neck anteriorly

- Longus capitis: Flexes and stabilizes the head

- Rectus capitis anterior: Flexes head forward

In addition:

- Platysma: Draws lower lip and neck skin downward

The deep intrinsic muscles between vertebrae also facilitate movement and stability:

- Intertransversarii laterales/anteriores/posteriores

- Inter spindles

Many shoulder girdle muscles like the trapezius and pectoralis directly articulate with the cervical vertebrae as they move the shoulders and attach the upper extremity to the axial skeleton.

The complex cervical musculature coordinates movement and stability to support critical functions like breathing and upright head posture. Cervical muscle strains are common causes of neck pain and stiffness.

Causes and Risk factors of cervical spondylosis:

Aging/Degenerative Changes

- As we age, the intervertebral discs in the cervical spine lose hydration and volume, leading to disc degeneration and shrinkage beginning around age 40.

- The discs flatten and osteophyte bone spurs can form as the body tries to stabilize the cervical segments. This causes compression of nerves and the spinal canal.

- Degeneration of the facet joints from cartilage loss also progresses with age and contributes to symptoms.

Genetics

- Studies suggest some people may have genetic predispositions to accelerated disc degeneration. Gene mutations affecting collagen fibers and proteoglycan content may make discs more fragile.

Mechanical Stress/Accumulated Injury

- Chronic repetitive loading from work strains and poor neck postures accelerates wear and tear on the discs and vertebrae over time.

- Past injuries, whiplash from accidents, and sports impacts can also contribute to early cervical changes.

Other Factors

- Smoking: Associated with more rapid disc degeneration by impairing nutrient transport into discs.

- Obesity: Increased weight places more compressive loads on the cervical spine during movement.

- Metabolic conditions like diabetes are linked to elevated inflammation that can accelerate cervical spondylosis progression.

In summary, while cervical spondylosis largely results from age-related degenerative processes, genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors also determine the rate of disc and joint deterioration each experience. Understanding these causes is key to prevention efforts.

Epidemiology of cervical spondylosis

Prevalence

- Cervical spondylosis is an extremely common age-related condition. More than 85% of people over age 60 show radiographic evidence of cervical degenerative changes.

- Symptomatic cervical spondylosis resulting in neck pain or radiculopathy is estimated to occur in about 5% of the overall population.

- Prevalence increases markedly with age – while only around 3% of those under age 45 are affected, almost 60% of people over age 60 have symptomatic cervical spondylosis.

Sex Differences

- Males tend to develop cervical spondylosis and related disorders like disc herniations at younger ages than females on average.

- However, by age 65, females catch up with or surpass males in the prevalence of cervical spondylosis. Hormonal effects might be the cause of this.

- Studies show males have higher rates of spondylotic myelopathy (spinal cord compression) while females experience more cervical radiculopathy symptoms.

Racial Variations

- Whites have a somewhat higher prevalence of symptomatic cervical spondylosis compared to African Americans and Hispanics in many studies.

- Asians including Chinese and Japanese populations also show variation in gene frequencies related to lumbar disc degeneration risk, suggesting potential genetic differences by ethnicity – however more evidence is needed specifically for the cervical spine.

Global Differences

- Developed countries with an older average population age and advanced imaging utilization show higher diagnosis rates of cervical spondylosis. However, true disease prevalence is likely similar globally.

- Increased digital device usage and sedentary lifestyles in younger generations are also expected to drive greater future spondylosis incidence worldwide.

So in summary, while nearly universal radiographically, symptomatic cervical spondylosis in over age 60 populations exceeds 50% in many global regions and ethnicities – variation exists – and rates continue to rise.

Clinical presentation and Examination of cervical spondylosis

Symptoms

Non-Specific Neck Pain

- The most common initial symptom

- Aching or stiffness in the posterior neck

- Often radiates to the shoulders or base of the head

- Worsens with movement or sustained postures

- Sharp radiating pain following a dermatome into the shoulder/arm

- Arm weakness, tingling, or numbness

- Affects specific nerve root distribution

- C5 and C6 are most commonly affected

Cervical Myelopathy

- Leg stiffness or imbalance

- Fine motor coordination deficits

- Bladder dysfunction or increased urinary urgency

- Abnormal sensations in hands or feet

- Hyperreflexia, spasticity, positive Babinski sign

Physical Examination

Inspection

- Observe posture abnormalities, range of motion

- Atrophy or fasciculation of arm/leg muscles

Palpation

- Tenderness of cervical facet joints or paraspinal muscles

- Tightness or spasm of cervical muscles

Range of Motion

- Use of goniometer to assess flexion, extension, and rotation

Neurological

- Muscle strength testing

- Reflex evaluation

- Sensation to light touch, vibration

Advanced Testing

- Spurling’s test for radicular arm pain

- Lhermitte’s sign for neck flexion myelopathy

- MRI to characterize structural spondylosis changes

Physical Exam Findings

Key aspects of clinical examination that support a cervical spondylosis diagnosis include:

- Decreased cervical range of motion

- Presence of muscular guarding or cervical paraspinal tenderness

- Upper extremity radicular pain or myotomal weakness

- Positive Spurling’s test reproducing arm symptoms

- Decreased reflexes or sensation in affected nerve distributions

Diagnostic evaluations for cervical spondylosis:

X-ray

- Initial imaging study to assess bone spur formation, disc space narrowing, misalignments

- AP, lateral, and oblique views provide a view of foraminal stenosis, spinal canal diameter

- Flexion/extension views check stability

MRI

- A gold standard imaging test

- Allows visualization of spinal cord, nerve roots, intervertebral discs

- Quantifies degree of cord/nerve impingement

- Evaluate soft tissue causes of compression

CT Scan

- Better define bony pathology like facet arthropathy contributing to symptoms

- Typically ordered after MRI for further characterization

CT Myelogram

- Intrathecal contrast enhances the visualization of neural compression

- Alternative if MRI contraindicated due to hardware

EMG

- Assesses nerve conduction studies and muscle electrical activity

- Helps confirm cervical radiculopathy versus other neurological disorders

Discogram

- Invasive provocative testing of disc pathology

- Rarely necessary for neck pain evaluation

- Concern for accelerating disc degeneration with testing

Key aspects are correlating a patient’s symptoms and clinical exam findings with appropriate imaging like MRI to confirm the location and components driving cervical spondylosis pathology – while weighing the risks and benefits of more advanced evaluations like discography or myelography in select cases.

Differential Diagnoses

It’s important to rule out pain attributable to:

- Cervical strains or sprains

- Herniated disc with radiculopathy

- Spinal infections

- Underlying inflammatory arthritis

- Spinal tumor or fracture

Herniated Cervical Disc

- Cervical disc herniations that compress nerve roots may present very similarly with radicular pain and neurological symptoms.

- Disc herniations tend to occur in younger individuals after trauma. Spondylosis develops progressively over time.

- Imaging helps differentiate the anatomical causes of nerve impingement.

Cervical Strains/Sprains

- Muscular strains after awkward neck postures present with pain and stiffness but not radicular patterns.

- Typically develops after an incident and improves faster than spondylosis changes.

- Physical exam localizes pain to cervical musculature without neurological deficits.

Spinal Tumors

- Neoplasms of the cervical spine, whether metastatic or primary tumors, can also compress nerve roots and cause severe radicular or myelopathic symptoms mimicking spondylosis.

- Red flags like a history of cancer, unintentional weight loss, and persistent night pain prompt imaging to assess.

Cervical Arthritis

- Inflammatory arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis) can affect cervical facet joints and spinal structure, also prompting disc degeneration over time.

- Blood tests help diagnose underlying systemic inflammatory disease.

Vertebral Fractures

- Cervical compression fractures after major trauma, especially in the elderly, can produce both neck pain and neuropathic features which may overlap with spondylosis symptoms.

- Imaging confirms the acute vertebral body changes.

Taking a thorough history, conducting a full neurological exam, and utilizing imaging facilitates distinguishing cervical spondylosis from disc, bone, and joint disorders impacting the cervical segments – and guides appropriate management.

Symptoms of Cervical Spondylosis

Neck Pain

- Most common symptom

- Typically described as an aching or stiffness in the posterior neck

- Can be a dull persistent pain or sharp and episodic

- Often radiates to the base of the skull or shoulder blades

- Aggravated by neck movement or certain positions

Radicular Pain

- Sharp pain following dermatomal distribution into shoulder and arm

- Affects areas innervated by specific spinal nerves

- Radiates along typical patterns based on nerve root impingement

- Worsens with neck movements compressing nerve

Paresthesias

- Abnormal sensations like burning, tingling, or numbness

- Follows dermatomal patterns into the shoulder, arm, forearm, or hands

- Reflects nerve irritation due to inflammation or compression

Motor Weakness

- Muscle wasting over time from chronic nerve compression

- Upper limb weakness may precede sensory changes

- Most pronounced in hand intrinsic muscles

Reflex Changes

- Diminished muscle stretch reflexes in the affected limb

- Loss of biceps, brachioradialis, triceps reflexes

- Sign of advancing nerve damage

Myelopathic Symptoms

- Imbalance, difficulty with hand coordination, hyperreflexia

- Reflects spinal cord involvement producing long tract signs

- Bowel/bladder dysfunction is also possible

The symptoms of cervical spondylosis encompass localized neck discomfort along with pain, and sensory and motor disturbances following typical nerve root patterns – which may progress to myelopathic findings in severe cases. Careful history and examination are key to detecting the level and structures impacted.

Treatment of Cervical Spondylosis

Non-surgical medical management

Medications

- NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen) or acetaminophen: For pain and inflammation

- Muscle relaxants (e.g. cyclobenzaprine, tizanidine): For acute muscle spasms

- Nerve pain medications (gabapentin, pregabalin): For radicular pain

- Steroids (oral prednisone, local epidural injections): Reduce inflammation

Physical Therapy

- Manual therapy techniques: Massage, traction, manipulation

- Posture correction and neck stabilization exercises

- Range-of-motion and flexibility exercises

- Heat/ice therapy for pain relief

- Ultrasound or electrical stimulation

Bracing

- Soft or rigid cervical collars: Provide support and limit painful motion

- Prescribed for acute strains or after surgical treatment

Alternative Therapy

- Acupuncture: May help provide an analgesic effect

- Supplements: Omega-3 fatty acids, turmeric, glucosamine

- Stress reduction: Yoga, massage

Lifestyle Modifications

- Workplace ergonomic adjustments

- Regular exercise for weight control, cervical stability

- Proper sitting and standing posture habits

- Cold or warm compresses for symptomatic relief

Goals are restoring range of motion and strength, reducing pain levels, and reliance on medications over time through targeted physical therapy programs and self-management strategies.

Surgical management

Goals of Surgery

- Release spinal cord or nerve root compression

- Prevent the progression of neurological deficits

- Reduce intractable radicular or neck pain

- Improve functionality and quality of life

Approaches

- Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion (ACDF)

- Posterior Laminectomy and Fusion

- Combined Anterior-Posterior Surgery

ACDF Surgery

- Remove the anterior cervical disc and osteophytes

- Fuse vertebral bodies with bone graft

- May incorporate a cervical plate for stability

Posterior Surgery

- Laminoforaminotomy – relieves foraminal nerve compression

- Laminoplasty – expands space for cord without fusion

Minimally Invasive Options

- Microdiscectomy via tubular retractor system

- Endoscopic discectomy through small neck incision

Recovery

- Hospitalization 1-3 days

- Cervical brace for 6-12 weeks post-op

- Physical therapy for 3-6 months to strengthen neck muscles

Outcomes

- 90% experience significant pain relief after surgery

- Neurological recovery variable based on severity

- Fusion reduces but does not eliminate the risk of adjacent segment disease

Key considerations for surgery include approach, extent of decompression, need for fusion versus laminoplasty, and incorporating the least invasive methods possible. A thorough discussion of both non-surgical and surgical options is warranted.

Physical therapy management

Physical therapy is a core aspect of conservative management for cervical spondylosis. It focuses on relieving pain, improving range of motion, correcting posture deficits, and enhancing functional mobility of the cervical spine and upper extremities.

Manual Therapy

Hands-on techniques to mobilize tight joints and muscles, and increase movement in restricted spinal segments

Common approaches:

- Massage – Relaxes tense muscles contributing to pain

- Trigger point release – Targets muscle knots limiting mobility

- Traction – Gentle pulleys/weights decompress the spine

- Joint mobilization – Low-velocity spinal manipulations

Thrust Manipulation

- High velocity, low amplitude maneuvers

- Performed at the end of the joint’s passive motion range

- Quick, controlled force applied to “unlock” facet joints

- An audible pop may occur

- Evidence supports short-term relief of neck pain

Non-Thrust Manipulation

- Gentler techniques within the passive range of motion

- Sustained pressure avoids end-range thrust

- Examples: Muscle energy techniques utilizing body contraction against resistance

Postural Education

- Training optimal neck, shoulder, and torso positioning

- Avoiding repetitive strained postures that aggravate symptoms

- Workplace ergonomics evaluation

- Postural braces can provide cueing

The goals of physical therapy are reducing inflammatory triggers of pain, improving cervical mobility, fostering durable muscle strength through exercise, and emphasizing proper spinal mechanics during daily activities.

Electrotherapy modalities

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)

- Low voltage electrical current via surface electrodes over painful areas

- TENS blocks pain signals to the brain and activates pain-relieving endorphins

- Reduces neck and radicular pain from spondylosis

Interferential Current Therapy (IFC)

- Two alternating medium-frequency currents cross to target tissues

- Promotes calcium and sodium ion exchange to accelerate healing

- Reduces muscle spasm and post-activity soreness

Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation (NMES)

- Application of electrical current to enhance muscle strength

- Prevents atrophy from chronic nerve compression

- Improves activation of weak/paretic muscles

Iontophoresis

- Use electrical gradient to deliver anti-inflammatory medication through the skin

- Administers dexamethasone/salicylates without injections

Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Therapy

- Generates electromagnetic fields that reduce inflammation

- Portable devices allow home treatment sessions

- Evidence is limited for chronic neck pain

Electrical stimulation modalities like TENS and IFT can control acute flare-ups of neck and arm pain associated with cervical spondylosis. NMES strengthens muscles in compromised myotomes. Overall, electrotherapy is frequently included in multi-modal physical therapy programs.

Exercises for Cervical Spondylosis

Benefits of Exercise for Cervical Spondylosis:

If you engage in regular exercise, you experience the following benefits:

- Improves neck movement by reducing stiffness.

- Strengthens weak neck muscles and enhances range of motion.

- Increases flexibility of neck muscles that are stressed by cervical spondylosis.

- Relieves neck pain by releasing positive hormones and correcting posture.

- Helps release tension or tightness.

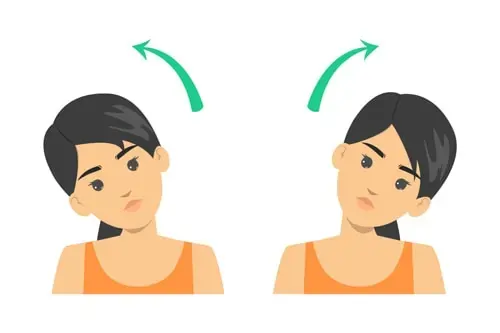

Head tilt (side-to-side)

This exercise helps stretch the neck muscles and can help relieve pain and stiffness from cervical spondylosis.

- Sit upright in a chair or stand with your arms relaxed at your sides. Keep your shoulders back and down.

- Slowly tilt your head toward your right shoulder as far as is comfortable without forcing it. Do not lift or shrug your shoulder on the tilting side.

- Hold this stretch for 5 counts.

- Slowly bring your head back to the center, again avoiding lifting or shrugging the shoulders.

- Now tilt your head toward your left shoulder, following the same guidelines. Hold for 5 counts.

- Repeat this sequence 5-10 times, alternating sides in a controlled, fluid motion. Focus on keeping the movement smooth rather than forcing the stretch.

- Take breaks as needed if you experience increased neck pain or dizziness. Over time, work up to holding the stretch for up to 30 seconds on each side.

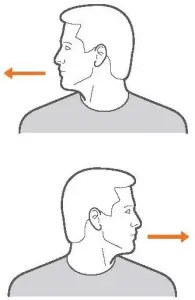

Neck Turn

- Sit upright in a chair with your shoulders relaxed and arms resting at your sides. Look straight ahead.

- Slowly turn your head towards your right shoulder as far as feels comfortable. Do not lift or tilt your shoulder upwards.

- Hold this position for 5 counts. Focus on feeling a gentle stretch on the left side of your neck. Breathe slowly.

- Turn your head back to the center and face forward again.

- Now turn your head to the left, letting it turn as far left as is comfortable without lifting your shoulder.

- Hold for 5 counts, feeling the stretch on the right side of your neck.

- Bring your head back to the center. This is 1 repetition.

- Repeat this sequence for 5-10 reps on each side. Move slowly and smoothly rather than forcing your neck to turn.

- Take breaks as needed if you feel pain. Over time, work up to holding the turn for up to 30 seconds on each side.

Neck Roll

- Sit upright with shoulders down and head facing straight forward.

- Slowly drop your right ear down toward your right shoulder, without lifting your shoulders. Along the left side of your neck, feel a slight stretch.

- In a smooth, circular motion, roll your chin down toward your chest. Let your head gently round forward with your chin slightly tucked as you continue rolling to the left.

- Continue rolling your head to tilt your left ear toward your left shoulder. Avoid crunching your head forward. Hold for 5 counts.

- Complete the circle by rolling your head around and back up to the center with your chin level and head straight forward.

- Reverse directions, beginning by tilting your left ear down to the left shoulder, then rolling your chin down to your chest and rounding your head to the right shoulder.

- Continue back up toward the center completing one full circle to the other side.

- Repeat 5-10 times slowly in each direction keeping the movement smooth. Focus on allowing the weight of your head to gently stretch your neck muscles throughout the range of motion.

Shoulder Rolls

- Sit tall with feet flat on the floor, arms relaxed at your sides.

- Initiate movement from your shoulders as you draw them up towards your ears. Avoid hunching your neck and keep your gaze forward.

- Roll shoulders backward and down in a circular motion.

- Continue rolling them all the way forward, up and around to complete one full revolution.

- Repeat 5-10 times slowly and with control. Focus on using the movement to relax tension in your neck, shoulders, and upper back.

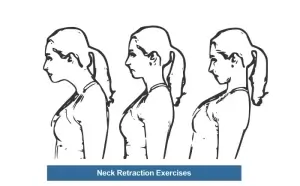

Cervical Retraction

- Sit or stand tall looking straight ahead. Engage your core muscles.

- Tuck your chin slightly toward your throat. Avoid poking your chin forward.

- Gently pull your head directly backward, keeping it level, as if to make a double chin. You should feel a slight stretch in the front of your neck.

- Hold this retracted neck posture for 5-10 seconds before slowly releasing back to neutral.

- Repeat 5-10 times. Work up to holding for 30 seconds. Remember to keep breathing smoothly.

Prone Cobra Exercise

- Lie face down on the floor with your forehead resting on a pillow.

- Lift your head, chest, and arms while keeping your elbows out to the side.

- Squeeze your shoulder blades together.

- Keep your forehead lifted off the ground, eyes looking up, and neck arched.

- Hold for 5 to 10 seconds.

- Return to the starting position and rest.

- Repeat this exercise 5 to 10 times.

Upper Trapezius Stretch:

- Tilt your head sideways toward your right shoulder. Placing your right hand behind your back is correct.

- Grasp your right elbow with your left hand and gently pull on your right elbow to deepen the stretch in the upper right trapezius area.

- Hold for 30 seconds and repeat on the left side.

- Complete the exercise 2-3 times on each side.

- Sit upright with shoulders down. Look straight ahead.

- Place your palm on the front left side of your forehead. Apply gentle pressure as you push your head back into your hand.

- Hold for 5-10 seconds. Focus on feeling the contraction in your neck muscles.

- Release the pressure and relax.

- Repeat on the right side, placing your palm on the right side forehead and pushing back.

- Complete 5-10 repetitions on each side.

Downward-Facing Dog

Downward-Facing Doggy is super helpful for opening up the front chest wall and shoulders, which are often rounded and stiffened from overuse tech usage.

Since upper-body strength is crucial, you may be compensating by raising your shoulders to your large ears if you lack shoulder strength. If you notice yourself doing this, actively put your shoulder blades down your back, which will create space in your neck.

How to do it:

- Begin on all your fours. Push your toes and lift your hips, reach your hip bones toward the ceiling!

- Reach your heels way back toward the mat, but do not let them touch the ground.

- Drop your head down so that your neck becomes long! As you stay here, be sure that your wrist should stay parallel to the front side of the mat.

- Apply pressure on the knuckles on your thumbs and not-so-tiny forefingers to ease the strain on your wrists.

- Take at least three deep breaths and then you releasement.

Exaggerated Nod

The odd gesture of the exaggerated nod pulls your shoulders down and back, enhancing neck mobility, and counteracting the downward and head position.

How to do it:

- With your arms at your sides and your legs comfortably stretched, face up, assume a supine position.

- Engage your core. Maintaining stability in your torso, gently nod your chin down towards your chest.

- Hold for 2 counts. Then lift your head back up, exaggerating the extension of your neck to feel a stretch. Avoid pressing the back of your head down.

- Hold for 2 counts. That’s 1 rep.

- Repeat for 10-15 reps slowly with control.

Cat-Cow

This exercise promotes spinal awareness, which is crucial for good posture. Your core, or pelvis, should drive the Cat-Cow flow. As you inhale, you create an anterior tilt to the pelvis so that your tailbone should face the ceiling, and as you exhale, you create a posterior tilt so that your tailbone is facing the ground.

How to do it:

- Start on all fours with your shoulders over your wrists, your hips stored over your knees, and the top part of your feet pressed into the ground lengthen your head to see a few inches in front of your fingers, look down to your tailbone.

- In order to initiate the “cow” phase, open your shoulders wide, keep your shoulders away from your ears, lift your chin and chest to gaze skyward, and swoop and scoop your pelvis so your belly sinks to the floor as you inhale.

- In order to initiate the “cow” phase, open your shoulders wide, keep your shoulders away from your ears, lift your chin and chest to gaze skyward, and swoop and scoop your pelvis so your belly sinks to the floor as you inhale.

- Repeatedly cycle through Cat-Cow will help to relieve strain and stress from the head and neck.

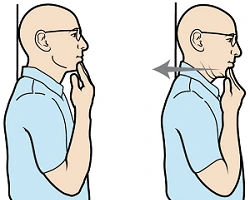

Chin Tuck – Exercise Guide

This easy stretch, which you can perform at work or at home, can help you become more aware of your spine and strengthen the muscles in your neck, which will help you bring your head back into alignment, adds Cappo.

How to do it:

- Stand with the wall support straight and keep your chin parallel to the ground.

- Take care to avoid tilting Gently bring your head and chin back, creating the illusion of a double chin, without swaying your head in any direction. your head back.

- All the way around the back of your neck should feel stretched.

How do you select the proper pillow for cervical spondylosis?

Cervical pillows are specially designed to provide neck support and maintain proper spinal alignment when sleeping. Their shape is contoured to cradle the neck area rather than just the head. The materials and designs aim to give comfortable ergonomic support for the neck. Transitioning from a regular pillow can feel uncomfortable initially, but using a cervical pillow daily, even for short rests, allows your neck to adjust.

Proper pillow choice depends on your regular sleeping position. Back sleepers need a pillow that conforms to the head and neck to keep the neck supported. Memory foam or water pillows are good back sleeper options as they mold to your shape but still provide support.

Side sleepers need a firm pillow to avoid over bending the neck. Place more bulk under the neck than the head to keep the spine aligned. An elasticated pillow can conform more readily to shifts in position. The pillow interior is divided into rectangular segments so the fill adjusts with you. Non-elastic pillows simply have top and bottom panels sewn together. Putting another pillow between the knees also helps side sleepers maintain spinal posture.

Stomach sleeping can strain the back without proper support. Use a very thin pillow or none at all to avoid arching the back excessively. Placing additional thin cushioning under the midsection can also minimize back discomfort for stomach sleepers.

Travel pillows in a horseshoe shape provide needed neck support when sitting semi-upright. Whether in cars, planes, or trains, they prevent the head from tilting sideways during fitful travel sleep which can aggravate neck pain.

Proper Ergonomics

- Maintain proper posture – Keep neck aligned over shoulders without slouching/straining. Use small lumbar cushions if the chair has no lower back support.

- Take regular short breaks – Take a brief break every 30-60 minutes to get up, stretch, or change positions to avoid sustained awkward postures. Set reminders if needed.

- Get a supportive chair – Sit in a chair with good lumbar and upper back support to keep your back aligned. Adjust the height so feet can rest flat on the floor with thighs parallel to it. Add a neckrest if desired.

Use proper equipment set-up:

- Position the monitor directly in front at eye level to avoid neck strain.

- Place keyboard and mouse pads to keep elbows at a 90° angle.

- If on the phone frequently, use a headset instead of tension in the neck from holding the phone between the ear and shoulder.

- Modify activities requiring sustained positions – Avoid activities like reading, writing, or needlework in sustained awkward head-forward posture for long periods. Take frequent short breaks.

Complications associated with cervical spondylosis:

Neurological Dysfunction

Cervical spondylosis can progress over time and result in increasing spinal cord or nerve root compression. This may lead to:

- Myelopathy – Leg stiffness, loss of dexterity, hyperreflexia from spinal cord involvement

- Radiculopathy – Worsening arm pain, numbness, and weakness from nerve impingement

- Bowel or bladder incontinence in severe cases – requiring prompt surgical evaluation

Spinal Cord Injury

In rare cases, acute disc herniation or traumatic facet dislocation/fracture can occur on top of chronic degenerative changes, risking spinal cord injury. Patients may develop paralysis or Central Cord Syndrome marked by disproportionate upper extremity dysfunction and sensory loss.

Adjacent Segment Disease

Up to 25% probability of new degenerative problems developing at levels adjacent to previous cervical fusion site in 10 years – likely reflecting natural history.

Post-surgical Complications

Surgeries like Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion carry anesthesia risks, infection risks, habeas/fluid collection, graft complications, hardware failure, or painful fibrous tissue formation requiring additional interventions.

Chronic Pain Syndrome

A subset of patients may progress to central sensitization with heightened pain signaling, depression, sleep disruption, and disability requiring pain psychology approaches.

Careful serial examination is warranted in conservative management to promptly address evolving myelopathy or radiculopathy. Surgical risks merit thorough consideration of alternatives, however, intervention is indicated for progressive neurological deficits before the development of permanent spinal cord injury.

Prevention strategies

- Maintain good posture: Whether sitting, standing, or lying down, keep your head aligned over your shoulders without slouching or craning your neck forward. Avoid hunching over desks, phones, or while reading.

- Use ergonomic equipment: Use ergonomic chairs, desks, keyboards, phone headsets, and other equipment to promote better posture and less strain on the neck. Keep computer screens at eye level to avoid neck bending.

- Exercise regularly: Do strength training for the neck, back, and core muscles to provide more support. Low-impact aerobic exercise also helps manage weight and promote spinal flexibility.

- Take regular movement breaks: If doing repeated tasks in sustained postures, take microbreaks every 30 minutes to get up, stretch, and reposition. Set reminders if necessary.

- Use hot/cold therapy: Apply ice and heat packs to tight neck muscles that are painful or inflamed to stimulate blood flow and relieve spasms.

- Get physical therapy: See a physical therapist for neck stretches, stabilization exercises, massage, and manual techniques like traction to improve alignment and manage symptoms.

- Manage stress levels: Chronic stress leads to clenched, stiff muscles so practice relaxation techniques regularly. Get enough sleep since fatigue also raises muscle tension.

- Avoid smoking: Smoking limits spinal blood flow and speeds up age-related degeneration so quit smoking and tobacco use to protect the cervical spine.

- Use proper lifting mechanics: Bend knees and keep back straight when lifting heavy loads instead of hunching or twisting which can strain the neck. Ask for help to move larger items if necessary.

Summary

Cervical spondylosis is an extremely common age-related condition affecting the cervical discs and vertebrae, causing progressive degenerative changes like bone spur formation, disc space collapse, and ligamentous hypertrophy which result in spinal canal and nerve root compression.

It typically manifests first with neck pain and stiffness, along with possible referral patterns into the head, shoulders, and upper back. As it advances, more severe compression leads to cervical radiculopathy marked by radiating arm pain, and numbness/tingling into a dermatomal pattern. In severe cases, cervical myelopathy can occur featuring hyperreflexia, balance difficulties, and dexterity issues indicating spinal cord involvement.

Diagnosis relies on a combination of radiographic evidence of degeneration along with correlating clinical findings. Initial management emphasizes physical therapy for mobility and posture, anti-inflammatory medications, and possibly epidural injections for pain relief.

However, surgery like anterior cervical discectomy/fusion may become necessary for a refractory root or cord compression producing significant neurological deficits. Quality of life can be maintained with a thorough understanding of the condition’s pathogenesis and multi-modal treatment options through coordinated care.

FAQs

Which cervical spondylosis symptoms are most prevalent?

Neck pain, stiffness, and radicular symptoms like arm pain, numbness, and tingling in typical nerve root distributions.

What causes cervical spondylosis?

Age-related disc degeneration, genetics, and mechanical stress from occupational or sports impact the cervical spine over time.

How is cervical spondylosis diagnosed?

Imaging tests like X-rays and MRI correlated to clinical findings on examination like decreased range of motion and neurological deficits.

What treatments are available for cervical spondylosis?

Conservative approaches emphasize medications, physical therapy, and injections. Surgery like ACDF may be appropriate in select moderate to severe cases.

What activities make cervical spondylosis worse?

Conservative approaches emphasize medications, physical therapy, and injections. Surgery like ACDF may be appropriate in select moderate to severe cases.

Does cervical spondylosis lead to arthritis?

It reflects similar degenerative processes but differs in which cartilage breakdown occurs first – discs versus synovial joints with arthritis.

Is heat or cold better for cervical spondylosis?

Heat helps relax muscles before activity, while ice reduces acute inflammation associated with flare-ups. Contrast therapy using both modalities is reasonable.

What specialist treats cervical spondylosis?

Physiatrists, orthopedic spine surgeons, neurosurgeons, pain management physicians, physical therapists, and others collaborate in both nonoperative treatment and surgical decision-making.

References

- Cervical spondylosis – Symptoms & causes – Mayo Clinic. (2023, November 18). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/cervical-spondylosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20370787

- Kuo, D. T. (2023, May 1). Cervical Spondylosis. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551557/

- Cervical Spondylosis. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Cervical_Spondylosis

- Parmar, R. (2022, November 20). Cervical spondylosis: Cause, Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatment, Exercise. Mobile Physiotherapy Clinic. https://mobilephysiotherapyclinic.in/cervical-spondylosis-treatment-exercise/

- Solanki, V. (2022, November 4). Exercise for Cervical spondylosis. Samarpan Physiotherapy Clinic. https://samarpanphysioclinic.com/exercise-for-cervical-spondylosis/

12 Comments