Central Nervous System (CNS)

Introduction

The central nervous system (CNS) is a division of the nervous system that analyses and integrates different intrapersonal and extrapersonal information and produces a coordinated reaction to these stimuli.

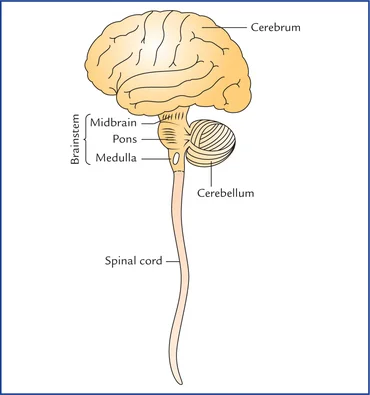

The brain and spinal cord are the two continuous central nervous system (CNS) organs. They are contained in two bony structures, the skull, and the vertebral column, respectively, and are surrounded and shielded by three layers of meninges. The brain is made up of the brainstem, cerebellum, subcortical regions, and cerebrum. From the brainstem, the spinal cord extends inferiorly down the vertebral canal.

Numerous neural channels allow the various sections of the brain and spinal cord to interact with one another while evaluating the data and planning appropriate bodily reactions. When the finished product is prepared, they send it directly from it to the rest of the body through peripheral nervous system (PNS) neurons.

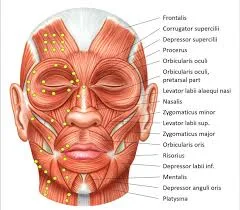

In particular, the spinal cord produces 31 pairs of spinal nerves, whereas the brain produces 12 cranial nerves that innervate the head, neck, thoracic, and abdominal viscera. Both the viscera and the rest of the body that is not innervated by the cranial nerves (upper and lower limbs) are innervated by the spinal nerves.

Structure

Grey and white matter

Neurons are the primary cells that receive and send neural impulses in the brain and spinal cord. Under a microscope, the body of each neuron, which serves as its micro-command center, appears grey. Two or more neural processes that originate in the body and transmit the neural information are present in the neurons. There are two types of neuronal processes: long (axons) and short (dendrites). A material known as myelin envelops the majority of axons, giving them a recognizable white color.

We refer to the components of neurons as grey and white matter. The myelinated axons of neurons make up the white matter, whereas clusters of neuronal bodies make up the grey matter. Instead of being haphazardly weaved throughout the brain tissue, the axons are arranged into bundles that link specific grey matter regions and provide the necessary impulses. These bundles are known as routes and tracts in the central nervous system (CNS) and nerves in the peripheral nervous system (PNS).

The brain and spinal cord have a very unique distribution of grey and white matter.

The cerebral cortex, which makes up the majority of the brain’s grey matter, is located on the outside, whereas the inside section is made up of white matter. Deep within the white matter that makes up the subcortical structures like the diencephalon and basal ganglia are smaller clusters of grey matter. The term “nucleus” (plural: “nuclei”) refers to any grey matter unit beyond the cortex in the brain.

When seen in cross-section, the grey matter, which makes up the inner portion of the spinal cord, resembles a distinctive butterfly. The grey matter is surrounded externally by the white matter, which is made up of spinal cord tracts.

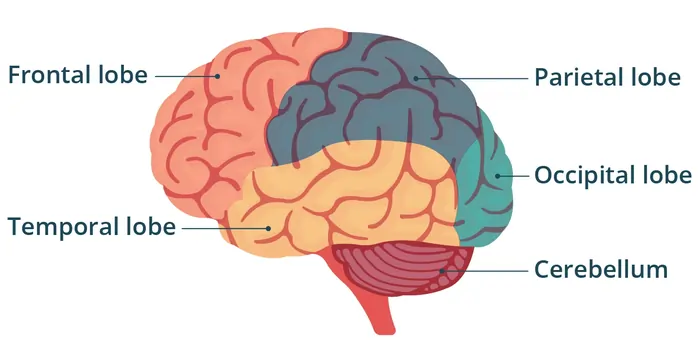

Cortex and brain lobes

The most noticeable area of the brain is the cerebrum, sometimes known as the forebrain. The corpus callosum connects the two brain hemispheres that make up this structure. The cerebrum has a very uneven surface made up of gyri (folds) and sulci (ridges). The cerebrum has the greatest processing capacity and cognitive abilities in the entire nervous system because of the sulci and gyri, which enhance its surface area. The five areas known as cerebral lobes—frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital, and insular—make up each hemisphere.

Every lobe of the brain performs a distinct set of tasks. For this reason, the entire brain is mapped out and separated into functional regions like the sensory and motor cortex. These cortical regions are further separated into main, secondary, and associated areas according to their degree of function. These hierarchical subdivisions work closely together to interpret information and produce appropriate motor or sensory bodily reactions.

Specific sulci delineate each lobe, which is in charge of various tasks. The central sulcus (of Rolando), which divides the precentral and postcentral gyri, is the most noticeable. The principal motor and primary somatosensory cortices are located there, respectively. These are the areas that sense feelings and activate motor processes. The white matter of the cerebrum, which makes up the majority of the deep cerebral structures, is surrounded by grey matter.

Subcortical structures

Deep within the brain is a collection of neuronal structures known as subcortical structures. They consist of the pituitary gland, limbic system, diencephalon, and basal ganglia.

Diencephalon

- Thalamus, comprises four groups of nuclei: the thalamic anterior, medial, lateral, and intralaminar nuclei. It is an oval nuclear mass. Sensory and motor data are sent to and received by the cerebral cortex via the thalamus.

- Epithalamus stands for the diencephalon’s most posterior region. It is made up of the habenular trigone, stria medullaris, and pineal body. The epithalamus has a role in initiating and controlling movement as well as the circadian rhythm, or sleep-wake cycle.

- Subthalamus, The thalamus is situated ventral to it. It includes the peri peduncular nucleus, zona incerta (of Forel), and subthalamic nucleus. The subthalamus is involved in the regulation, coordination, and precision of motor action.

- Hypothalamus, is situated inferiorly to the thalamus. It is separated into three zones (periventricular, medial, and lateral) and three groups of nuclei (anterior, middle, and posterior). Through several hypothalamic axes and the hypophyseal portal system, the hypothalamus controls metabolism, reproduction, and the stress response.

Basal ganglia

The lowest portion of the cerebrum, diencephalon, and midbrain are home to a collection of grey matter nuclear masses known as the basal ganglia. The caudate nucleus, putamen, globus pallidus, substantia nigra, and subthalamic nucleus are some of these nuclei. The striatum is made up of the putamen and caudate nucleus.

The extrapyramidal motor system includes the basal ganglia. To improve motor abilities, they use direct, indirect, and hyperdirect channels to connect with the thalamus.

Limbic system

The brainstem, subcortex, and cerebrum are all parts of the limbic system. The limbic cortex and deep limbic structures are its two divisions. The frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes’ many cerebral sulci and gyri combine to form the limbic cortex. The olfactory cortex, diencephalon, hippocampal formation, amygdala, brainstem, basal ganglia, and the basal portion of the cerebrum make up the deep portion of the limbic system.

The limbic system’s overall job is to regulate emotions, smells, and homeostasis. The hippocampus formation, which is involved in long-term memory and spatial navigation, is one specific significant component of the limbic system. Furthermore, fear is processed by the amygdala.

Brainstem

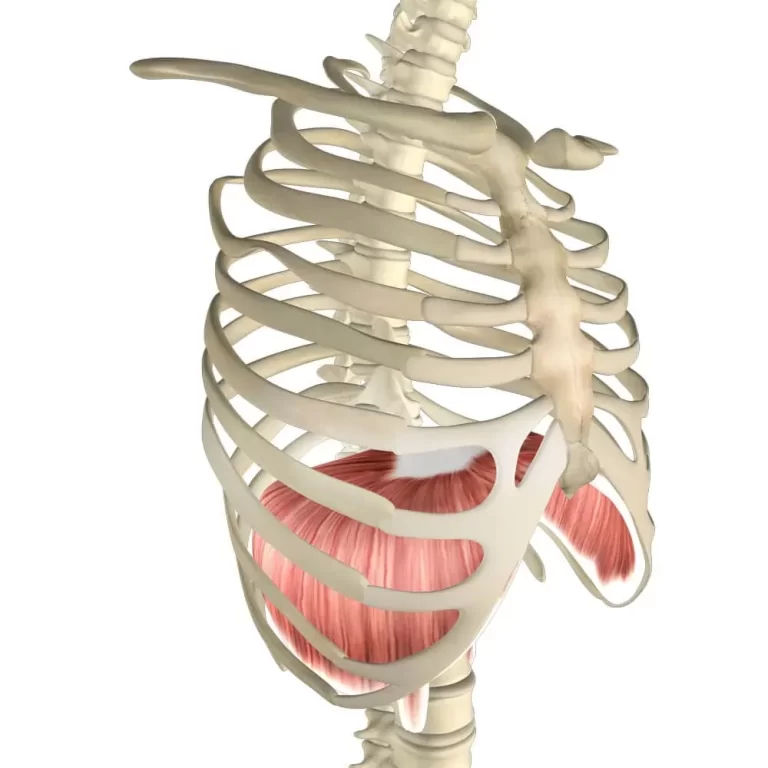

The brain’s inferior region is known as the brainstem. It is made up of the medulla oblongata, pons, and midbrain and is located in the posterior cranial fossa. It is separated internally into the tectum, tegmentum, and basal region. There are three primary and significant roles for the brainstem:

- Most of the cranial nerves’ nuclei are located there.

- makes it easier for neuronal pathways to go from the brain to the spinal cord.

- controls vegetative processes such as breathing, blood pressure, heart rate, and gastrointestinal activity.

Midbrain

The brainstem’s most superior region is the midbrain. It lies between the pons inferiorly and the thalamus superiorly. The midbrain controls body temperature, attentiveness, and visual and auditory responses. The mesencephalic branches of the basilar artery supply it.

Two cerebral peduncles, the interpeduncular fossa, the red nucleus, and the oculomotor nerve (CN III) are among the significant structures found in the front portion of the midbrain. Conversely, the midbrain’s posterior region has four prominences known as colliculi (superior, inferior).

The quadrigeminal plate (corpora quadrigemina) is made up of these colliculi. The posterior portion is also where the trochlear nerve (CN IV) arises.

Pons

The medulla oblongata and midbrain are separated by the pons, the central part of the brainstem. Numerous processes, including sleep, hearing, swallowing, taste, breathing, balance, and motor activities, are mediated by the pons. The basilar artery’s pontine branches provide its blood supply.

Numerous significant landmarks may be seen on the anterior portion of the pons, including the basilar groove, the superior and inferior pontine sulci, and the striations made by the corticopontocerebellar tract fibers. From the anterior portion of the pons, four pairs of cranial nerves emerge: vestibulocochlear (CN VIII), facial (CN VII), abducens (CN VI), and trigeminal (CN V). The superior part of the rhomboid fossa, medial eminence, posterior median sulcus, facial colliculus, striae medullares, locus coeruleus, and vestibular regions are located on the other side of the pons, in the posterior portion.

Medulla oblongata

The brainstem’s most inferior region is called the medulla oblongata. It controls autonomic processes involved in reflex, vasomotor, respiratory, and cardiac functions. The anterior spinal artery and inferior cerebellar artery provide blood to the medulla oblongata.

Numerous protuberances and developing cranial nerves may be found on the anterior portion of the medulla oblongata. These consist of the vagus nerves (CN X), hypoglossal (CN XII), glossopharyngeal (CN IX), pyramids, olives, and anterior median fissures. Numerous significant anatomical features, including the posterior medial sulcus, cuneate fasciculus, gracile fasciculus, cuneate tubercle, gracile tubercle, trigeminal tubercle, lateral funiculus, inferior part of the rhomboid fossa, and obex, are also visible on the posterior side of the medulla oblongata.

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is situated behind the brainstem and fourth ventricle in the posterior cranial fossa. The tentorium cerebelli divide it from the cerebrum. Furthermore, the superior, middle, and inferior cerebellar peduncles serve as the cerebellum’s anchors and channels of communication with the brainstem. The cerebellum is responsible for motor learning as well as motor activity coordination and accuracy. The anterior inferior (AICA), superior (SCA), and posterior inferior (PICA) cerebellar arteries provide blood to the cerebellum.

The three components of the cerebellum are two hemispheres on either side of the central vermis. The inferior (occipital) surface faces inferiorly, whereas the superior (tentorial) surface points superiorly. The three lobes (anterior, posterior, and flocculonodular) and roughly ten lobules (I–X) that make up the cerebellum are separated horizontally.

Spinal cord

The medulla oblongata is the inferior continuation of the spinal cord. It reaches the level of the L1/L2 vertebrae from the skull’s foramen magnum. 31 pairs of spinal nerves emerge from the five segments that make up the spinal cord: the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal.

Three sulci, one anterior fissure, and four surfaces make up the spinal cord. On the inside, it is made up of white matter around a center of grey matter. The vertebral and segmental arteries provide the spinal cord with its blood supply.

Information transmission between the brain and the rest of the body is the spinal cord’s job. In addition, the spinal cord governs lower body processes independently from the brain, such as reflexes.

Meninges

The brain and spinal cord are surrounded by three membranes, which are represented by the meninges. The meninges of the spinal cord are known as spinal meninges, while the meninges of the brain are known as cranial meninges. Through the foramen magnum, the cranial and spinal meninges are joined together. The meninges support blood arteries, protect the central nervous system, and contain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The meninges, from superficial to deep, consist of:

- Dura mater – The periosteal and meningeal dura mater make up its two-layered sheath. The periosteal layer of the brain securely attaches the dura mater to the skull. The epidural gap divides the spinal dura (theca), which envelops the spinal cord, from the vertebral column. The dural venous sinuses are located in a gap created by the layers of the cerebral dura diverging from one another in many places.

- Arachnoid mater – Below the dura mater are the cranial and spinal arachnoid. The subdural space is the area between the dura and the arachnoid.

- Pia mater -The surfaces of the brain and spinal cord are firmly adhered to by the cranial and spinal pia maters, respectively. The CNS’s surfaces are nourished by the many blood vessels that make up the extremely vascular pia mater. The spinal pia inferiorly continues the cranial pia mater, which covers the whole brain. Beyond the S2 vertebra, the spinal pia ends as the filum terminale, which is located above the spinal cord. The subarachnoid space is the area between the arachnoid and the pia mater. It includes the brain and spinal cord’s CSF and superficial blood vessels. Additionally, it has arachnoid granulations, which are mushroom-like protrusions through the dura mater that cover it and serve as the primary pathway for CSF removal.

Brain ventricles and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

The colorless fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord is called cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The choroid plexus, a specialized tissue located inside the walls of the brain ventricles, produces it. Before being reabsorbed into the venous system via the subarachnoid granulations, the CSF passes successively via the ventricles and subarachnoid cisterns. The CSF’s roles include protecting the central nervous system, supplying it with nutrition, and absorbing mechanical force.

The cavities filled with CSF that are buried deep inside the brain parenchyma are known as the brain ventricles. There are four ventricles in the brain: two lateral ventricles in the cerebrum’s lobes, one-third ventricle in the middle of the hemispheres, and a fourth ventricle behind the brainstem.

Five foramina connect the ventricles and allow the CSF to flow through the ventricular system:

- The space between the third ventricle and the lateral ventricles is known as the interventricular foramen (of Monro).

- Sylvius’s cerebral aqueduct, which connects the third and fourth ventricles.

- Between the cerebellopontine cistern and the fourth ventricle are two lateral openings (of Luschka).

- Magendie’s median aperture (between the fourth ventricle and the subarachnoid space’s cisterna magna)

Neural pathways and spinal cord tracts

The axon bundles that link several neurons are known as neural pathways. The connections between the various components of the brain might be made only inside the brain, or they can be made between the brain and the spinal cord.

The tracts are the names given to the passageways that go through the brain. Tracts are used to transfer information across the different areas of the brain as a stimulus is analyzed and integrated. The structures that the tracts link are typically used to determine their names. For instance, the corticonuclear tract is a passageway that links the cranial nerve nuclei to the cerebral cortex.

The ascending (sensory) and descending (motor) tracts are neural channels that link the brain and spinal cord. They transmit motor and sensory data from the central nervous system to the peripheral nervous system. The spinal cord’s white matter contains spinal cord tracts. They are made up of three-order neurons that synaptically connect sequentially. The classification of spinal cord tracts is as follows:

- Ascending tracts, spinocerebellar (proprioception, coordination, posture), spino-tectal (spin visual reflex), spino-reticular (consciousness), spino-olivary (cutaneous, proprioception), and dorsal column (fine touch, proprioception) are all examples of ascending tracts.

- Descending tracts include the vestibulospinal (balance), reticulospinal (facilitating or inhibiting voluntary and reflex actions), tectospinal (auditory and visual reflexes), rubrospinal (fine involuntary movement), corticospinal (voluntary movements), and corticobulbar (influences cranial nerve activity) pathways.

Function

What are the central nervous system’s three primary roles?

Your central nervous system performs the following three primary tasks:

- Receive sensory information.

- Process the information it receives (integration).

- Respond with motor output.

Your brain sends an electrical signal to your muscles and glands via your spinal cord to produce a motor output once it has received and processed the information gathered by your sensory neurons, or nerve cells. Desiring to cross the room is an illustration of this process. Your spinal cord relays a signal from your brain to your leg muscles. This signal is received by your muscles, which then enable you to finish the activity (motor output) of walking.

How does the central nervous system work?

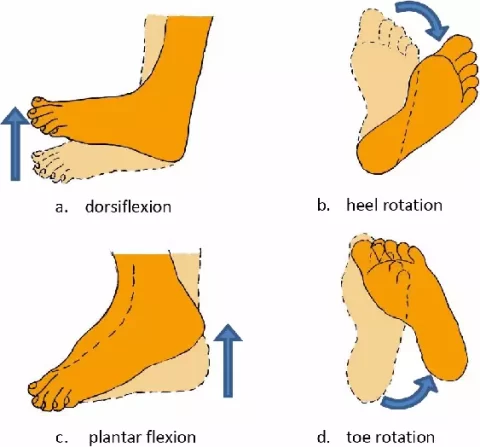

Your ideas, emotions, and movements are all controlled by your brain. It controls your actions, including learning, talking, and bending your fingers. Additionally, it controls how your organs work by instructing you on how to breathe and digest food. Although you probably don’t, your central nervous system does.

Messages are sent through your nervous system to accomplish this operation. A message is produced by your brain. That signal, or message, is transmitted to your spinal cord. To finish an action, your peripheral nervous system (PNS) receives a signal from your spinal cord. To keep your body working, signals are continuously sent to and from your brain and spinal cord to the rest of your body.

Embryology

In the third week of embryonic development, the adult brain and spinal cord develop. The neural plate is formed by the thickening of the ectoderm. The neural groove is then formed by the neutral region folding inward. The neural groove is flanked by laterally migrating neural folds. The CNS structures are formed by the neural tube, which emerges from the neural groove.

The anterior and posterior ends of the neural tube split apart. The spinal cord develops from the posterior end, while the principal brain vesicles, prosencephalon (forebrain), mesencephalon (midbrain), and rhombencephalon (hindbrain) grow from the anterior end. Secondary brain vesicles are produced while the original brain vesicles continue to differentiate. The hindbrain divides into the metencephalon and the myelencephalon (spinal brain), whereas the forebrain divides into the telencephalon and diencephalon. The midbrain remains in the mesencephalon and does not split. The adult brain structures are created by the secondary brain vesicles developing.

- Telencephalon to cerebrum

- Diencephalon to hypothalamus, thalamus, retina

- Mesencephalon to the brain stem (midbrain)

- Metencephalon to the brain stem (pons), cerebellum

- Myelencephalon to the brain stem (medulla oblongata)

Ventricles are continuous, hollow chambers formed by the center portion of the neural tube. The cerebral hemispheres continue to expand throughout the sixth month of pregnancy, causing the cerebral cortex to transform from a smooth to a wrinkled, convoluted look. The grooves are called sulci, while the raised portions of the ridges are called gyri.

The larger brain surface area can fit inside the skull thanks to the convolutions. There are white matter and grey matter regions all across the brain. Glia, unmyelinated neurons, dendrites, and neuronal cell bodies are all found in the grey matter. On the other hand, myelinated axons make up white matter.

Grey and white matter make up the spinal cord, which is created from the caudal part of the neural tube. The dorsal alar and ventral basal plates are formed when the grey matter collects about 6 weeks of gestation. The basal plate gives rise to motor neurons, whereas the alar plate produces interneurons. Neural crest cells give birth to dorsal root ganglia, which transmit information from the periphery to the spinal cord.

Clinical Importance

Wernicke Aphasia

The most prevalent cause of Wernicke aphasia is an ischaemic or hemorrhagic stroke. The Wernicke region cannot get oxygenated blood due to strokes in the left middle cerebral artery. A person with Wernicke’s aphasia can make speech and talk clearly. They struggle to grasp words, though, and their communication is meaningless.

Broca Aphasia

Brain injuries, brain tumors, or strokes can result in Broca aphasia, sometimes referred to as expressive aphasia. The Broca region of the brain loses oxygen when a stroke happens there. Damage from hypoxia is irreversible. When someone develops Broca aphasia, they have trouble speaking. They can understand and know what they want to express, but they are unable to put it into words.

Traumatic Brain Injuries

When normal brain activity is disrupted, as might happen in sports injuries, auto accidents, piercing objects, or even blunt objects, the result is a traumatic brain injury (TBI). Depending on how severe the injury was, TBI symptoms might change. For instance, although a contusion results in long-term brain damage, a concussion might produce momentary lightheadedness or unconsciousness. Coma is the outcome of brain stem contusions. TBI can result in cerebral edema and subdural or subarachnoid hemorrhage. The brain’s blood vessels shatter when the brain is traumatized. As the blood starts to accumulate, the brain tissue is compressed and the intracranial pressure rises.

Cerebrovascular Accidents

Strokes, another name for cerebrovascular accidents, happen when the brain cannot get oxygen-rich blood. Hypoxia results from low oxygen levels, and brain tissues begin to deteriorate. Strokes are frequently caused by a blood clot that has made its way to the brain’s cerebral artery from another part of the body.

The symptoms of the stroke depend on where the clot settles. For instance, some persons may have slurred speech, while others may suffer left-sided paralysis. Since the symptoms of transient ischaemic attacks are more transient, they are regarded as little strokes. Time is of the essence in any cerebrovascular event. If required, doctors can surgically remove the clot or use tissue plasminogen activator to break it up. The length of time the brain’s oxygen supply has been interrupted is directly correlated with the intensity of symptoms.

Alzheimer Disease

A prevalent form of dementia called Alzheimer’s disease causes the brain’s cells and neural connections to deteriorate and eventually die. Cognitive impairment and memory loss are the symptoms of this illness. Alzheimer’s disease progresses over time, and its symptoms get worse. Researchers have discovered tau-based neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid plaque aggregations in Alzheimer’s disease patients’ neurons. The misfolding of proteins within brain cells causes these plaques and tangles, which ultimately lead to the death of brain cells. Neural activity in the hippocampus, basal forebrain, and parietal cortex is reduced in Alzheimer’s disease patients.

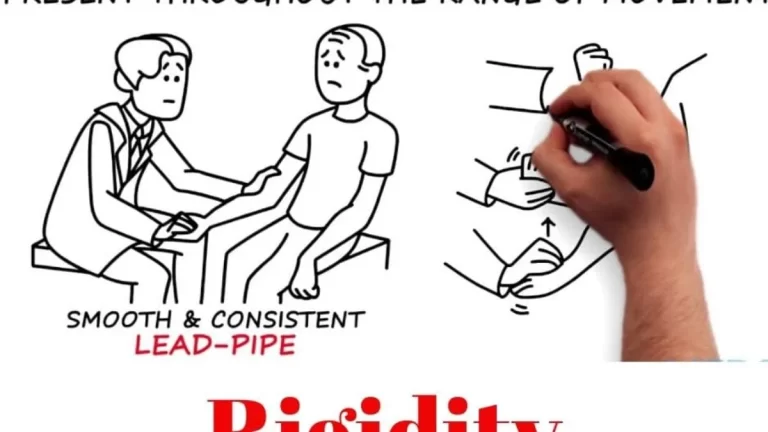

Parkinson Disease

Parkinson’s disease is a condition of the nervous system that causes the substantia nigra’s dopamine-releasing neurons to deteriorate. Tremors, uneven movements, and loss of balance are caused by the decline in dopamine levels. Since Parkinson’s disease typically begins as a hand tremor, it progresses over time. As symptoms worsen, many patients experience bradykinesia, rigidity, a mask-like face, and a pill-rolling motion in their palms. After examining the patient’s symptoms, medical history, and neurological and physical examination, a Parkinson’s disease diagnosis is made.

The condition has no known treatment, however it is possible to manage how severe the symptoms are. For usage in the central nervous system, levodopa can go through the blood-brain barrier and be converted into dopamine. One surgical approach for controlling tremors is deep brain stimulation, which can reduce aberrant brain activity. Deep brain stimulation, however, does not stop the condition from becoming worse.

Huntington Disease

A mutation in the huntingtin gene (HTT) causes Huntington’s disease, a degenerative, inherited brain condition. The HTT gene’s CAG region typically repeats up to 35 times. The CAG section, however, can be repeated up to 120 times in a person with Huntington’s disease. The huntingtin protein builds up in brain cells as a result of this big CAG region, ultimately resulting in cell death. Huntington’s disease first manifests as hand flapping, involuntary jerking, and chorea. Cognitive impairment happens as the illness worsens. Within 15 years after diagnosis, death occurs.

Spinal Cord Traumas

The location of spinal cord damage affects their symptoms. Sensation may be impacted if the sensory tracts sustain injury. However, paralysis results from injury to the ventral horns or roots. When nerve impulses fail to reach the targeted muscles, it results in flaccid paralysis. The muscles cannot contract if they are not stimulated. Involuntary contraction of the motor neurons due to irregular stimulation is known as spastic paralysis. If the spinal cord is severed between T1 and L1, the result is paraplegia or paralysis of the lower limbs. A cervical injury causes quadriplegia, which is paralysis of all limbs.

Poliomyelitis

The poliovirus causes poliomyelitis, an inflammation of the spinal cord. People can contract poliovirus from one another or contaminated food and water. It causes paralysis by destroying the neurons in the spinal cord’s ventral horn. It is possible to prevent poliovirus infection by administering the vaccination.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Motor neurons that regulate both voluntary and involuntary actions, such as speaking, swallowing, and breathing, are destroyed in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also referred to as Lou Gehrig’s disease and ALS. Unfortunately, there is no treatment for ALS, and its etiology is unclear. Researchers think that ALS patients’ elevated levels of extracellular glutamate are linked to cell death. Riluzole slows the course of ALS and lessens its excruciating symptoms by interfering with the production of glutamate.

In multiple sclerosis, an autoimmune illness, the body targets the central nervous system’s myelin proteins, impairing the brain-body connection. In young people, multiple sclerosis is quite common and manifests as discomfort, weakness, loss of eyesight, and impaired coordination. Patients differ in how severe their symptoms are. Medication can assist manage the negative symptoms of this illness by suppressing the body’s immune system.

Surgical Importance

To execute unpleasant medical treatments that would otherwise be impossible, anesthesia is a controlled condition of temporary loss of feeling. Anesthesia comes in a variety of forms, including local, sedative, and general. Nonetheless, they are all employed to interfere with intracellular and cellular communication in the peripheral and central nervous systems.

Amnesia, paralysis, and an analgesic are all used in general anesthesia, which causes the patient to go unconscious. General anesthesia results in a complete lack of feeling and full suppression of central nervous system activity. Intubation and subsequent mechanical breathing are necessary while using neuromuscular blockers.

Depolarisation results from the binding of depolarising neuromuscular blockers, such as succinylcholine, to postsynaptic cholinergic receptors. Future depolarisations are avoided because succinylcholine is removed from the receptors much more slowly, which inhibits acetylcholine binding. Vecuronium and other nondepolarizing neuromuscular blockers disrupt postsynaptic cholinergic receptors by acting as acetylcholine inhibitors. These neuromuscular blockers do not alter the ion channels’ permeability when they bind, though.

The anaesthesiologist simply numbs the area of the body that will be operated on during regional anesthesia. Spinal and epidurals are injected into the vertebral canal and utilized as local anesthetics. Whereas the epidural injection is administered into the epidural space, spinal anesthesia targets the spinal fluid.

Undergoing anesthesia has a risk, just like any surgical operation. Obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and any respiratory or cardiovascular disease process raise the chance of problems.

Neurosurgeons are trained to diagnose and treat conditions that impact the central nervous system. They offer surgical treatment for neurological conditions such as tumors, strokes, injuries to the head and spine, persistent pain, etc. There are dangers associated with every surgical treatment, particularly when working with sensitive brain and spinal cord nerve tissue. Brain hemorrhage, speech, memory, coordination problems, stroke, brain edema, and even coma are all consequences of brain surgery.

FAQs

Which seven major CNS components are there?

The seven fundamental components of the central nervous system—which includes the brain and spinal cord—are generally accepted to be the cerebral hemispheres, the medulla, the pons, the cerebellum, the midbrain, the diencephalon, the spinal cord, and the medulla.

What happens if the CNS is damaged?

In general, mature neurons usually fail to recover after CNS damage, leading to a persistent loss of motor function.

Can CNS nerves be repaired?

The central nervous system of mammals cannot renew its neurons. Significant strides have been achieved in determining the molecular and cellular processes underlying regenerative failure and how modifying those pathways might support axon regeneration and/or cell survival.

Which three problems of the neurological system are most prevalent?

Among the most common nervous system disorders are Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, and epilepsy.

Here’s a more detailed look at these disorders:

Alzheimer’s Disease:

memory, cognition, and behavior are the main areas affected by this progressive neurodegenerative disease.

Stroke:

A condition where blood supply to the brain is interrupted or reduced, leading to brain damage.

Epilepsy:

A neurological condition characterized by recurrent seizures, which are sudden, uncontrolled electrical disturbances in the brain.

How is CNS treated?

The following therapies may be used to treat recently discovered primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma: radiation treatment for the whole brain. Chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy. only targeted treatment (ibrutinib, nivolumab, or rituximab).

References

- Central nervous system. (2023, November 3). Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/the-central-nervous-system

- Professional, C. C. M. (2024f, December 19). Central Nervous System (CNS). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/central-nervous-system-cns

- Thau, L., Reddy, V., & Singh, P. (2022, October 10). Anatomy, central nervous system. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542179/

4 Comments