Thoracic Spine

What is the Thoracic Spine?

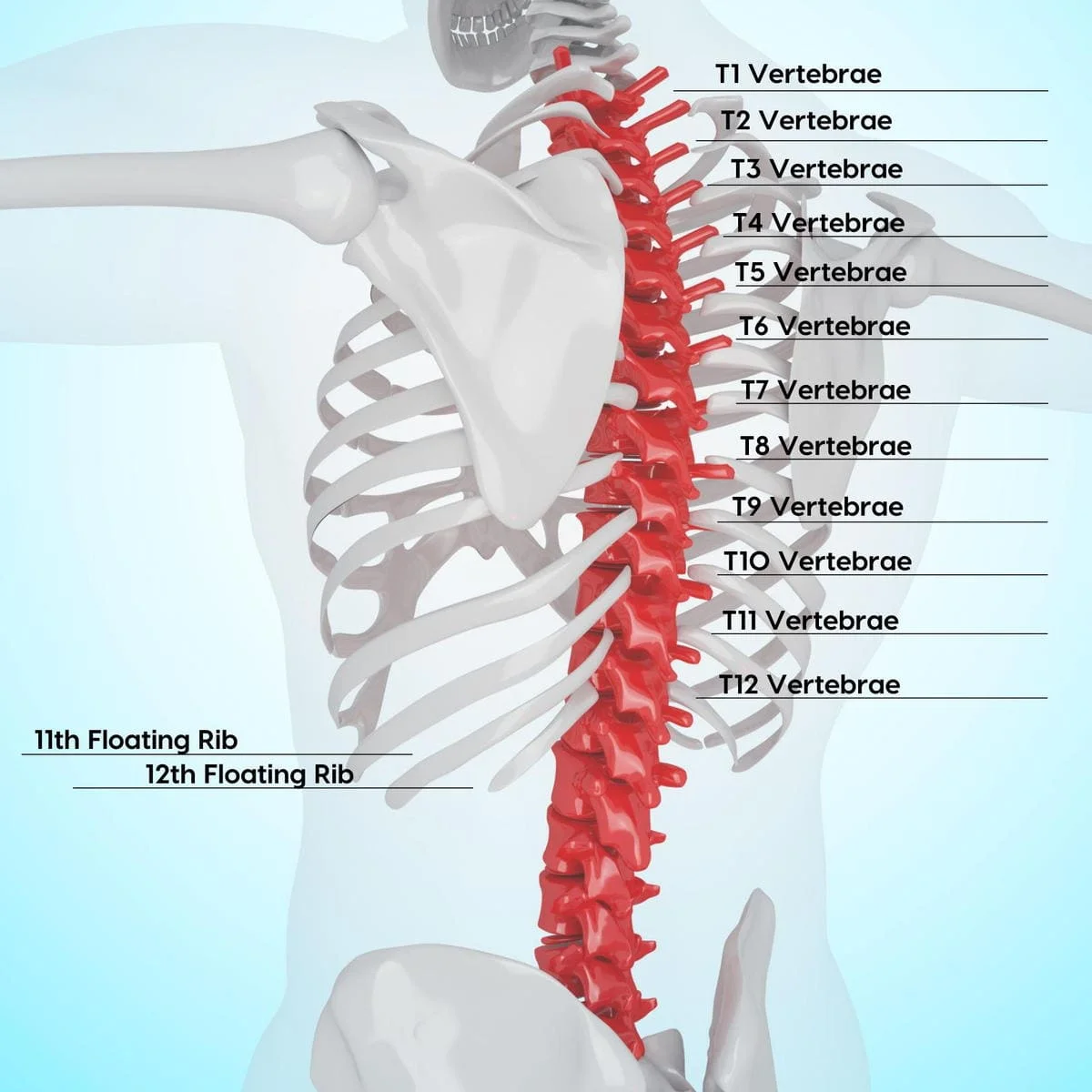

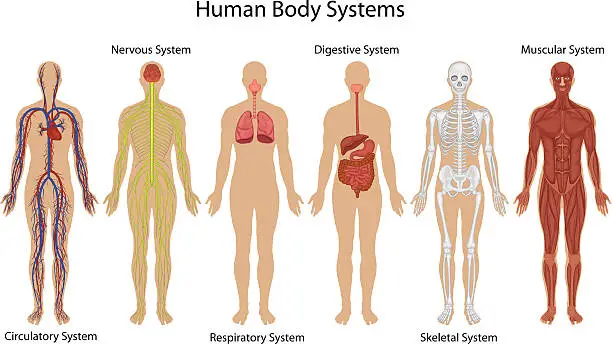

The thoracic spine, also known as the upper or middle back, is a crucial region of the vertebral column situated between the cervical and lumbar spine. Consisting of twelve vertebrae (T1-T12), the thoracic spine plays a pivotal role in providing structural support, protecting vital organs, and facilitating various bodily movements.

The long, flexible column of bones that makes up your spine, or backbone, is what protects your spinal cord. It terminates in your tailbone, which is a component of your pelvis and starts at the base of your head.

The following components make up your spine:

- Cervical spine (neck).

- Thoracic spine (upper and middle back).

- Lumbar spine (lower back).

The center portion of your spine is called the thoracic spine. It terminates at the base of your ribs after beginning at the base of your neck. Your spine’s longest segment is this one. There are 12 vertebrae in your thoracic spine, numbered T1 through T12.

The 33 separate, overlapping bones that make up your spinal column are called vertebrae. These bones enable you to twist and turn while also aiding in the prevention of damage to your spinal cord. There are disks in between your spinal bones that give your vertebrae support and flexibility.

In addition, your thoracic spine is encircled by tendons, ligaments, muscles, and nerves that facilitate flexibility and movement. Your entire spine is centered on your spinal cord. Your brain, which regulates every element of your body’s operations, sends and receives messages through it.

Function of the Thoracic Spine

The thoracic spine serves a number of essential functions, such as:

Keeping your spinal cord, and spinal nerve branches safe:

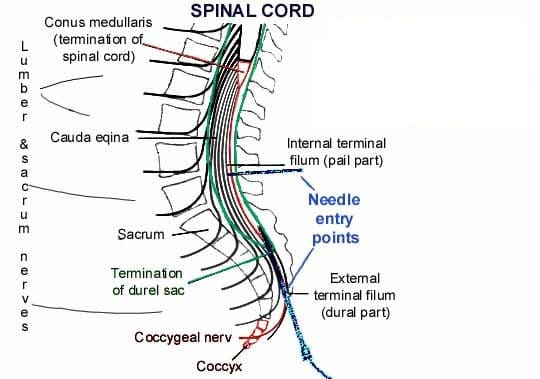

The vertebral foramen, a sizable opening in the middle of each vertebrae in your spine, is where the nerves of your spinal cord pass. Your spinal cord is protected by the protective central canal formed by the overlapping of all the vertebrae in your spine.

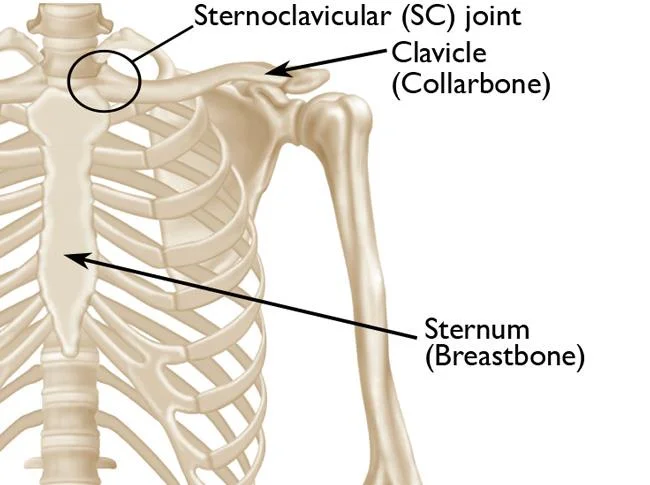

Providing attachments for your ribs:

With the exception of the two at the base of your rib cage, thoracic vertebrae are special in that they serve as attachment points for your ribs.

Supporting your abdomen and chest:

Your rib cage supports and stabilizes your thoracic spine, which in turn supports and stabilizes your rib cage. Your ribcage and thoracic spine work together to safeguard your heart and lungs. Your thoracic spine’s joints are both sufficiently flexible to permit breathing and sufficiently tight to safeguard these important organs.

Permitting your body to move:

You may bend and twist without compromising the stability of your spinal column thanks to the soft intervertebral disks that sit between your vertebrae. You can rotate your spine as much as possible thanks to the joints in your thoracic spine. But of your entire spine, the thoracic area has the least amount of flexion or extension.

Your spine naturally curves in three different directions. The “c-shaped” curves known as lordosis are formed by the lumbar spine (low back) and cervical spine (neck). A kyphotic curve, often known as a “reverse c-shaped” curve, is created by the thoracic vertebrae collectively.

These curves support your upright posture and are crucial for balance.

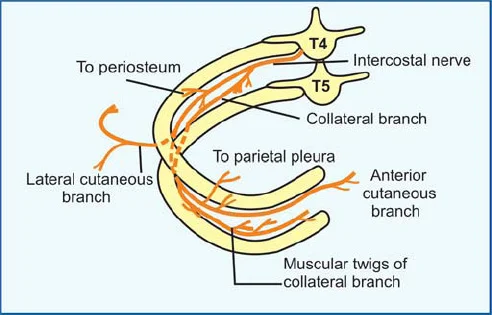

Which nerves leave the thoracic spine?

There are 12 vertebrae in your thoracic spine, designated T1 through T12. The nerves in that particular region of your spinal cord also correlate with each number. Certain parts of your body receive movement and sensation from these nerves, which emerge from your spinal cord.

Your thoracic spine nerves do the following tasks:

Nerves T1 and T2:

These nerves run into your hands and arms, as well as the upper part of your chest. The brachial plexus, a network of nerves in your shoulders that transmits movement and sensory information from your spinal cord to your hands and arms, includes the T1 nerve as well.

Nerves T3 through T5:

Your chest wall is penetrated by these nerves. These neurons work in combination to regulate your breathing muscles, lungs, diaphragm, and rib cage.

Nerves T6 to T12:

Your back muscles and abdomen are affected by these nerves. These nerves aid in coughing as well as balance and posture, in conjunction with specific muscles.

Which organs is the thoracic spine involved in?

The thoracic spine’s branching nerves from your spinal cord carry signals from your brain to your main organs, such as your:

Heart, liver, small intestine, and lungs.

Your heart and lungs are protected by the combined strength of your rib cage and thoracic spine.

Where is the thoracic spine situated?

Your upper and middle back meet in the center where your thoracic spine is situated. It starts at the base of your neck (cervical spine) and finishes just above your lower back (lumbar spine), encircling your rib cage.

What is the thoracic spine made of?

Your thoracic spine is made up of numerous components, such as:

Vertebrae:

Of the 33 mounted vertebrae (small bones) that make up your spinal canal, 12 make up your thoracic spine. Your spinal cord and nerves are located in a tunnel called the spinal canal, which protects them from harm. To enable range of motion, these vertebrae move.

Facet joints:

The cartilage, the slippery connective tissue, in these spinal joints enables the vertebrae to glide past one another. Facet joints offer stability and flexibility in addition to allowing for twisting.

Intervertebral discs:

These rounded, flat cushions serve as shock absorbers for your spine by resting in the space between your vertebrae. Every disk has a flexible outer ring encircling a soft, gel-like center.

Spinal cord and nerves:

A column of nerves that passes through your spinal canal is called your spinal cord. Your lower back is connected to your skull by a cord. Along your spine, 31 pairs of nerves split off through neural foramen or vertebral holes. In the thoracic spine, there are twelve pairs of nerves that split off. These nerves transmit signals from your brain to your muscles.

Soft tissues:

Your vertebrae are connected by ligaments, which keep your spine in place. Your muscles allow you to move and support your back. Tendons help to produce motions by joining muscles with bones.

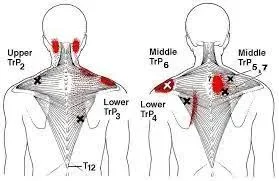

Muscles Attach to Thoracic Spine

Many muscles have attachment sites on the thoracic vertebrae:

- erector spinae

- interspinales

- intertransversarii

- latissimus dorsi

- multifidus

- rhomboid major

- rhomboid minor

- semispinalis

- serratus posterior superior/inferior

- splenius capitis

- splenius cervicis

- trapezius.

Blood Supply

The posterior intercostal artery branches provide the majority of the blood supply to the thoracic vertebrae. While the remaining posterior intercostal arteries branch off the thoracic aorta, the first two branch off the subclavian artery.

These principal arteries divide into the equatorial and periosteal arteries, which then split into the anterior and posterior canal branches. To supply the red marrow, nutritional arteries are sent into the vertebral body by anterior vertebral canal branches.

Lymphatics Drainage

Venous plexuses are created by spinal veins both inside and outside the spinal canal. Because these plexuses lack valves, blood can flow either superiorly or inferiorly based on pressure gradients. Eventually, the blood empties into the trunk’s segmental veins.

Nerve Supply

All vertebrae are innervated by the spinal nerves’ meningeal branches.

Embryology

Around eight weeks during the embryonic stage of development, all vertebrae start to ossify. They ossify from three main sites: one in each neural process (which will become the pedicles) and one in the endochondral centrum (which will become the vertebral body). This moves in both the cranial and caudal directions, starting at the thoracolumbar junction. Between the ages of three and six, the neural processes and the centrum merge.

Five secondary ossification centers form on the superior and inferior surfaces of the vertebral body, at the tip of the spinous process, and on both transverse processes throughout puberty. The superior-inferior growth of the vertebrae is caused by the ossification centers on the vertebral body. The process of osseous completion ends at about age 25.

Clinical Significance

Which common factors lead to pain in the thoracic spine?

Compared to the lumbar (lower back) and cervical (neck) spines, the thoracic spine is far less prone to injury because it is much more solid and stiff.

To protect your spinal cord, your back is made up of numerous interrelated bones, nerves, muscles, ligaments, and tendons. Your upper and middle back, or thoracic area, may be affected by a variety of illnesses that can cause pain in these tissues, such as:

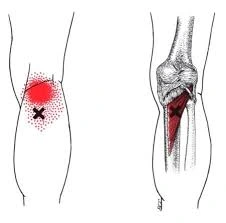

Tension or muscular irritation:

Prolonged sitting and bad posture can cause your thoracic region to become inflamed, causing pain and tense muscles.

Sprains of the ligaments:

A Thoracic sprain occurs when a ligament over-stretches or tears. Ligaments in the thoracic region of your spine may overstretch beyond what is safe in response to an abrupt twisting motion. Your thoracic region may hurt as a result.

Trauma:

Pain may arise after a fall or a direct hit to the thoracic region. But unlike your cervical and lumbar spines, the thoracic spine is more stiff, making it require more power to fracture. Injury to the rib cage can also cause pain in the thoracic area because it affects the thoracic nerves.

Overuse injuries:

Repetitive motions are frequently the cause of overuse injuries. They lead to the development of micro-injuries, which might result in back pain. Overuse injuries of the thoracic spine can result from repetitive lifting, bending, and twisting activities.

More typical thoracic spine pain causes that affect your spinal column directly include:

Spinal tumors:

Although they can develop anywhere in the spine, spinal tumors most frequently affect the middle and lower back. They often come from cancer that has spread. The most typical sign of both malignant (cancerous) and benign (noncancerous) spinal tumors is back pain. A spinal tumor typically causes intense, throbbing pain that sometimes keeps going during the night and interferes with sleep.

Spinal fracture:

While lumbar and cervical fractures are more common than thoracic spinal (vertebral) fractures, individuals with osteoporosis are more susceptible to thoracic spinal fractures because of their weaker bones. For those who have osteoporosis, a quick twisting action or sneeze might result in thoracic spinal fractures.

Degenerative changes of the Thoracic Spine:

Spondylosis, degenerative disc disease, and spinal osteoarthritis are all considered “degenerative changes of the spine.” The soft disks that serve as cushions between the vertebrae in your spine deteriorate, dry out, or shrink with age. This causes some problems by narrowing the area between your vertebrae.

Your neck (cervical spine) and lower back (lumbar spine) are more susceptible to these degenerative changes than your upper and middle back (thoracic spine).

Disorders that particularly impact your thoracic spine’s nerve roots, spinal cord, and/or vertebrae include:

Kyphosis:

Kyphosis is a spinal disorder characterized by a more forward rounding of the back, which results in a slouching or “hunchback” posture. When the thoracic spine, which makes up your upper back, becomes more wedge-shaped, it might result in kyphosis. There are three types of kyphosis: Scheuermann’s disease, posture-related, and congenital (occurring from birth).

Scoliosis in children and adolescents:

A child with a deformity known as pediatric or adolescent scoliosis will have an abnormally curved or rotated spine. You can have mild to severe scoliosis. When you have scoliosis, your thoracic spine is typically the most impacted. Scoliosis can also strike adults.

Thoracic radiculopathy:

A pinched nerve root in the thoracic spine (upper back) can result in thoracic radiculopathy, which is characterized by pain, tingling, and/or numbness that radiates to the front of the body. The least likely site of radiculopathy is your thoracic spine.

Additional conditions that may impact any part of your spine, including the thoracic area, consist of:

Osteophytes, or spurs on bones:

Bone spurs are growths or projections of the bone that form around tendons or cartilage. They most commonly affect the cervical and lumbar spine areas, although they can also happen close to joints in the thoracic spine, which is the mid-back and upper back.

Disk herniation:

A tear in the disks that act as a cushion between vertebrae is the cause of this disorder. Intervertebral disks make it easy for you to move and bend. Comparatively speaking to cervical and lumbar disk herniations, thoracic spine herniated disks are less common.

Myelopathy:

A group of symptoms known as myelopathy are caused by severe spinal compression. Your spinal cord might become compressed or squeezed and become dysfunctional. This may result in pain, loss of feeling, or trouble moving particular body parts.

Osteomyelitis:

Osteomyelitis is a condition caused by bacteria or fungi that affects the bone, specifically the vertebrae in your spine. Vertebrae may die if treatment is not received.

Spinal cord injury:

A quick, violent impact on any vertebrae in your spine, particularly your thoracic spine, causes the majority of spinal cord injuries. The spinal cord and its nerves are therefore harmed by the fractured (broken) bones. Your spinal cord may occasionally be totally severed, or divided. Because of its comparatively narrow vertebral canal, the thoracic spine is more vulnerable to damage to the spinal cord.

Spinal stenosis:

This disease results from the narrowing of the spinal canal. Your spinal cord and the nerves that branch off of it have less room in your spine when there is less space inside it. Your spinal cord or nerves may get inflamed, crushed, or pinched due to a tighter space.

The most common injury to the Thoracic Spine

The most frequent injury to the thoracic spine is a vertebral compression fracture (VCF). They arise from the collapse of a vertebra in the spine, which can cause excruciating pain, deformity, and height loss.

Particularly common in the lower thoracic region, compression fractures are frequently caused by minor trauma and osteoporosis. However, they can also occur as a result of tumors on your spine or more severe damage (such as a car crash) in the absence of osteoporosis.

Symptoms of Thoracic Spine Nerve Damage

The type of nerve damage (full or incomplete) and the location of the injury along the thoracic spine determine the symptoms of a thoracic spine nerve and spinal cord injury.

The primary signs and symptoms include tingling, weakness, and/or pain that travels to your arms, legs, or the area surrounding your ribs.

Damage to the thoracic spine nerve may also be linked to the following symptoms:

- loss or reduction of sensation in your legs or arms.

- trouble breathing.

- loss of sensation in your lower abdomen or genitalia.

- loss of bowel or bladder control.

- diarrhea.

If, following an injury, you observe any of these symptoms, get medical help right once.

How are thoracic spine disorders diagnosed?

Your doctor will first take a medical history, review your prescription history, inquire about your symptoms, conduct a physical examination, prescribe tests, and do imaging scans.

Imaging and tests could involve:

Computed tomography (CT) scan:

This scan creates fine-grained images of your inside anatomy using X-rays and a computer. Your spinal canal’s size, shape, contents, and surrounding bone can all be seen on a CT scan. It aids in the diagnosis of osteophytes, bone spurs, bone fusion, and tumor- or infection-induced bone deterioration.

MRIs, or magnetic resonance imaging:

This test creates detailed images using radio waves, a computer, and a big magnet. It can show issues with spinal degeneration, disk herniation, infections, tumors, and problems with your spinal cord and nerves leaving your spinal column.

X-rays

X-rays use a tiny quantity of radiation to produce images of your soft tissues and bones. X-rays can reveal arthritis, disk issues, fractures, and issues with spinal alignment.

Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies:

Your nerves and muscles can be assessed for health and function with the use of an EMG. The speed at which an electrical impulse passes through your nerves is measured during nerve conduction studies. These examinations aid in identifying the location of nerve compression and any ongoing nerve damage.

A myelogram

This imaging examination defines your spinal cord and the nerves that leave your spinal column, as well as the interaction between your vertebrae and disks. It indicates whether your spinal cord, nerves, or nerve roots are being compressed by a tumor, bone spurs, or herniated disks.

Treatment

Many disorders affecting your thoracic spine can be treated with surgery as well as nonsurgical methods including physical therapy and epidural steroid injections (ESIs).

The cause, severity, and general state of your health all influence your thoracic spine problem treatment options. The optimum course of therapy for you will be decided upon jointly by you and your healthcare professional.

How can I maintain the health of my thoracic spine?

You can take a number of actions to maintain the health of your spine, such as:

When you sleep, give your spine a break:

Selecting the ideal pillows and mattress will help your spine to relax comfortably and supported while you sleep. When you sleep, try to maintain your natural spinal alignment with the support of pillows and proper posture.

Become more muscular in your back and abdomen:

To optimally support your spine, the muscles in your lower back and abdomen—often referred to as your “core” muscles—need to be strong and flexible.

Limit your sitting time and adopt proper posture:

Maintaining proper posture when sitting and standing is crucial for preserving your back’s natural curves. Aim to avoid prolonged sitting and take regular rests from the chair. Sitting puts greater weight on the disks in your lower back than standing does.

Put on supportive footwear:

Proper footwear offers a stable foundation that keeps your spine in its proper position. Consult your healthcare professional about the best kind of shoes for you and whether you need to wear inserts or orthotics.

Maintain healthy bones

Keep your bones strong and healthy by making sure your diet has adequate calcium and vitamin D. Find out from your healthcare professional how much is right for you. If you have osteoporosis or are at risk of developing it, this is very crucial.

When should I schedule a thoracic spine examination with my doctor?

Your lumbar spine (lower back) and cervical spine (neck) are more likely to suffer injury and produce pain than your thoracic spine due to their unique configuration.

It is more likely that your upper and middle back pain is the result of a strain on a muscle or ligament, which is typically short.

However, it’s crucial to consult your doctor if you get sudden or severe upper and/or middle back pain, especially if you have a history of cancer. This region of your spine is more susceptible to the development of spinal tumors.

In addition, it’s critical to visit the hospital right away if you sustain back trauma from a fall or auto accident.

Conclusion

Your spine’s thoracic area serves a number of vital purposes. Even though thoracic spine spinal injuries are less prevalent than cervical and lumbar spine spinal injuries, it’s still crucial to visit your doctor if you have chronic upper or middle back pain. They can order tests and conduct a physical examination to determine what might be causing your pain.

References

- Featured Image: Thoracic Spine Nerves and Subluxation. (n.d.). https://www.gallatinvalleychiropractic.com/blog/95256-thoracic-spine-subluxation

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Thoracic Spine. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/22460-thoracic-spine

- Waxenbaum, J. A. (2023, August 1). Anatomy, Back, Thoracic Vertebrae. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459153/

20 Comments