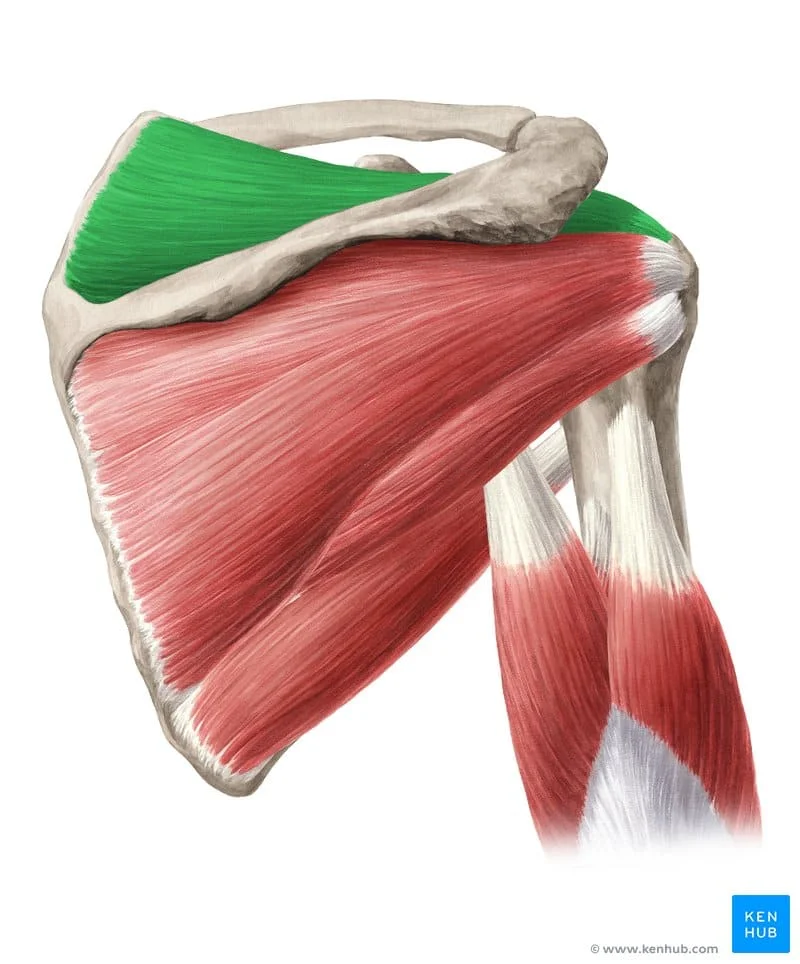

Supraspinatus Muscle

What Is The Supraspinatus Muscle?

The supraspinatus muscle is one of the four muscles that make up the rotator cuff, a group of muscles and tendons that stabilize the shoulder joint and facilitate its movement. It is located on the superior aspect of the scapula (shoulder blade) and plays a crucial role in initiating the abduction (lifting away from the body) of the arm at the shoulder joint.

The muscle tendon extends laterally, inserting into the superior facet of the greater tuberosity of the humerus after going under the acromion process and across the head of the humerus.

It then blends into the glenohumeral joint capsule. The supraspinatus contributes to the glenohumeral joint’s dynamic stabilization along with the teres minor, subscapularis, and infraspinatus, the other three rotator cuff muscles.

Together, these four muscles support the joint’s structural integrity by stabilizing the humerus’ head on the shallow glenoid fossa. Supraspinatus is linked to the abduction of the humerus in addition to its stabilizing function.

This movement may also have a minor effect on the lateral rotation of the humerus. Numerous studies have been conducted on the supraspinatus since it is the most commonly injured rotator cuff muscle. Although a lot is known about this tiny but crucial muscle, much more has to be discovered.

Structure of Supraspinatus Muscle

A dense fascia covering the subscapularis joins to the scapula at the borders of the attachment (origin) of the subscapularis.

After moving laterally from the muscle’s origin, the fibers of the muscle combine to form an insertion tendon. The tendon is entangled with the capsule of the glenohumeral (shoulder) joint.

A bursa sits between the tendon and a bare spot at the lateral angle of the scapula’s neck, communicating with the shoulder joint’s cavity through an aperture in the joint capsule. The serratus anterior and subscapularis are separated by the subscapularis (supra serratus) bursa.

According to Roh et al., the anterior belly’s structure is fusiform and derives solely from the supraspinous fossa. An internal tendon that creates a tendinous core into which the muscle fibers insert are found in the anterior belly.

The internal tendon developed extra-muscular and thickened into a tubular structure. Forty percent of the total breadth of the external tendon is derived from the tendon of the anterior belly.

The structure of the posterior belly is different from that of the anterior belly and is referred to as unipennate; this structure is less suited to producing high contractile stresses.

With no internal tendinous core, the posterior belly originated from the neck of the glenoid and the spine of the scapula, giving it a strap-like (Vahlensieck) appearance.

Sixty percent of the supraspinatus tendon’s thickness came from the posterior belly muscle fibers that were inserted straight into the bigger, flatter external posterior tendon.

The anterior tendon is 2.88 times more stressed than the posterior tendon, according to the authors’ further calculations of the tendon stress assigned to the anterior and posterior muscle bellies.

The two sections of the supraspinatus tendon were shown to have different histologic intratendinous structures; the anterior segment of the tendon displayed a double-layered interwoven pattern of fibers, while the posterior division of the tendon displayed thin, dispersed fibers. This result validated the study’s force calculations.

There are several ways to characterize the architecture of the supraspinatus muscle, ranging from fusiform to circumpennate.

The intricacy of the design is revealed by a more thorough examination of the structure using MRI tests. It was stated in 1993 that the anterior and posterior muscle bellies are a part of the supraspinatus.

Additional investigation has shown that the functions of the two bellies are different. In their description of the supraspinatus muscle’s structure, Roh et al. observed that, in each of the 25 embalmed cadaveric shoulders they studied, the posterior tendon was wider and flatter in form, while the anterior belly tendon was thicker and more tubular. They found that there was a 2.45 to 1 ratio between the mean cross-sectional area of the anterior and posterior muscle belly.

The tendon cross-sectional area ratio for the anterior and posterior bellies was also reported by the authors to be 0.9 to 1. This ratio shows that the anterior belly’s larger muscle mass applies force through a smaller tendon cross-sectional area than the posterior belly’s.

Although there is disagreement in the literature about how to calculate the tensile load from the physiologic cross-sectional area, it is important to note that the authors used ratios rather than absolute numbers to presume a linear relationship between the two variables.

The authors concluded that the anterior tendon would be subjected to up to 288% more stress than the posterior tendon based on the noted ratios.

The inferior part of the tendon merges with the joint capsule around 1 cm before the attachment to the bone. both the supraspinatus tendon and muscle deposit onto the super facet of the greater tuberosity of the humerus after passing deeply into the acromion process.

The transverse and coracohumeral ligaments are both continuous with the tendon’s superior section. The muscle may execute the humerus abduction function in this position and location.

Supraspinatus also has motor participation in the beginning and maintenance of abduction throughout the range of motion, in addition to the deltoid.

It has also been demonstrated that the supraspinatus makes a minor contribution to the humerus’s lateral rotation.

Supraspinatus, in conjunction with the other rotator cuff muscles, serves to prevent inferior displacement of the humeral head by working with the deltoid to maintain the humerus head on the glenoid fossa during joint motions.

Four structural subunits were found within the supraspinatus tendon by Fallon et al. after analyzing the histological morphology of the tendon: the tendon proper, the attachment fibrocartilage, the rotator cable (an extension of the coracohumeral ligament), and the capsule.

Function of Supraspinatus Muscle

The supraspinatus muscle mediates the humeral head toward the glenoid cavity and performs arm abduction. It keeps the humeral head from slipping inferiorly on its own.

When the arm is adducted, the supraspinatus and deltoid muscle collaborate to achieve abduction. Once the angle reaches 15 degrees, the deltoid muscle takes over as the primary means of causing the arm to abduct.

From the musculotendinous junction to the attachment fibrocartilage, the tendon proper section was located.

The anterior tendon’s more tubular, “rope-like” structure and the posterior tendon’s “thin strap-like” component, when combined, formed a broad point of attachment on the larger tuberosity, as was observed during the dissection.

There was a noticeable parallel arrangement of the collagen fibers and fascicles to the “axis of tension,” and histological staining revealed a significant amount of negatively charged glycosaminoglycans in areas where the individual fascicles readily detached and moved against one another.

In the anterior tendon compared to the posterior tendon, the fascicular organization within the tendon proper shifted to a basket-weave pattern of attachment fibrocartilage more proximally. Histologically, the attachment fibrocartilage region resembled compressively-susceptible fibrocartilage.

The rotator cable was found to be an extension of the coracohumeral ligament, which is situated between the tendon and joint capsule and perpendicular to the tendon proper’s axis.

It was discovered that the joint capsule was composed of thin sheets of collagen, with the orientation of the collagen fibers varying across layers but remaining constant within the sheets.

Collagen fibers in various patterns are arranged into a thin, robust structure when the sheets are linked together.

At a location directly medial to the supraspinatus tendon insertion on the greater tuberosity, the attachment fibrocartilage and the capsule are inseparable.

The inferior part of the tendon merges with the joint capsule around 1 cm before the attachment to the bone.

Both the supraspinatus tendon and muscle deposit onto the super facet of the greater tuberosity of the humerus after passing deeply into the acromion process.

The transverse and coracohumeral ligaments are both continuous with the tendon’s superior section. The muscle may execute the humerus abduction function in this position and location.

Supraspinatus also has motor participation in the beginning and maintenance of abduction throughout the range of motion, in addition to the deltoid.

It has also been demonstrated that the supraspinatus makes a minor contribution to the humerus’s lateral rotation.

Supraspinatus, in conjunction with the other rotator cuff muscles, collaborates with the deltoid to limit inferior displacement of the humeral head and stabilizes the humerus head on the glenoid fossa during joint motions.

Origin

It comes from the intermuscular septa (which form ridges on the scapula), the medial two-thirds of the costal surface of the scapula, and the bottom two-thirds of the groove on the scapula’s axillary edge, or subscapular fossa.

The aponeurosis, which divides the muscle from the teres major and the long head of the triceps brachii, is the source of some of the fibers.

Other fibers originate from tendinous laminae, which cross the muscle and are connected to ridges on the bone.

Insertion

It connects to both the smaller humeral tubercle and the anterior part of the shoulder joint capsule.

Tendinous fibers reach the bigger tubercle by penetrating the bicipital groove.

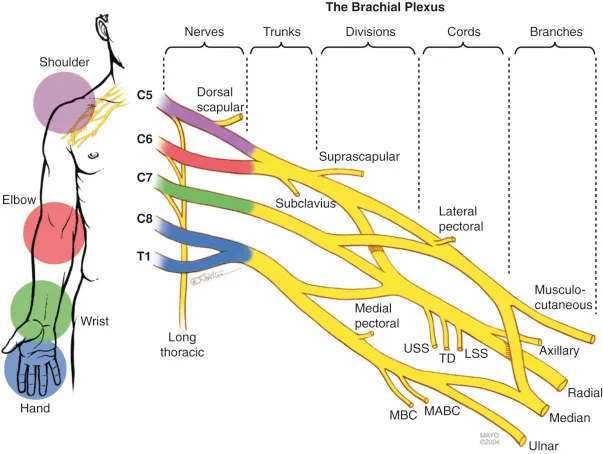

Nerve Supply

The suprascapular nerve, a branch of the brachial plexus’s upper trunk (C5–C6), supplies the supraspinatus with nerve fibers.

Action

It abducts the arm from 0 to 15 degrees when acting as the principal agonist.

allows the deltoid to generate abduction up to 90 degrees beyond this range.

Related Muscles

The teres minor, subscapularis, and infraspinatus are among the rotator cuff muscles that are associated with the supraspinatus.

It is connected to the deltoid embryologically and collaborates with it to abduct the humerus at the glenohumeral joint.

The glenohumeral joint is dynamically stabilized by the rotator cuff muscles, the deltoid, and the long head of the biceps brachii.

Blood Supply

The dorsal scapular and suprascapular arteries give blood to the supraspinatus. Although it can originate directly from the third portion of the subclavian artery, the suprascapular artery usually arises as a branch of the thyrocervical trunk, a branch of the subclavian artery.

The suprascapular artery travels inferiorly over the subclavian artery and brachial plexus before passing inferolaterally across the anterior scalene and phrenic nerve, deep to the internal jugular vein and sternocleidomastoid.

The artery will eventually arrive at the superior edge of the scapula, from whence it usually passes superior to the supraspinous fossa via the superior transverse ligament.

Both supraspinatus and infraspinatus will be supplied. The subclavian artery, usually the third portion, is the source of the dorsal scapular artery.

It will cross the middle scalene muscle, proceed posteriorly through the brachial plexus trunks, and then descend deeply to the levator scapula to reach the superior angle of the scapula, where it will start its journey alongside the dorsal scapular nerve. This artery supplies the surrounding muscles via anastomosing with the suprascapular and subscapular arteries.

Lymphatics

Deep lymphatic drainage normally follows the arteries, whereas superficial lymphatic drainage usually follows the veins.

The posterior subscapular nodes, which are connected to the subscapular vessels and situated along the inferior edge of the posterior axillary fold, are the principal lymphatic drainage points for the suprascapular region.

The central axillary nodes and the apical nodes will receive the efferent drainage from these nodes.

The subclavian lymphatic trunk, which drains to the jugular lymphatic trunk, the subclavian vein, the jugulosubclavian venous junction, or rarely a right lymphatic trunk, is formed by the combination of the efferent veins. The thoracic duct receives the left trunk’s drainage.

Anatomical Variantions

About 50% of the MRI images analyzed in research studies display an aponeurotic enlargement of the supraspinatus tendon next to the bicipital groove.

The anterior section of the supraspinatus tendon gave rise to this tendon-like structure, which went distally in a parallel orientation anterolateral to the long head of the biceps tendon and distally inserted on the superior side of the pectoralis major tendon.

The anterior tendon, which has a small insertion footprint on the larger tuberosity and functions similarly to the rotator cable of the rotator cuff interval, may be strengthened by this aponeurotic extension, according to the hypothesis.

Surgical Considerations

The anterior fibers must be included in the repair of the supraspinatus tendon whenever feasible to strengthen the muscle’s structure and function after the repair, as a result of the findings of Roh et al. The glenohumeral abduction and humeral head depression are the results of the anterior fibers and anterior tendon.

Functional impairment might occur if these fibers are not included in the repair. Although there have been theories in the literature that a torn rotator cuff could be the cause of shoulder weakness because of the shortened functional tendon, anterior tendon function loss and the loss of the main source of supraspinatus contractile load must also be taken into account.

Some studies discuss, among other things, the effects of opioids on postoperative outcomes, functional recovery following surgery, and a novel scoring system for healing following rotator cuff replacement.

As previously mentioned, there is a great deal of interest in this muscle, and numerous research articles about it have been published.

Clinical Importance

The functional differences observed after damage might be explained by structural variations in the anterior and posterior bellies of the supraspinatus muscle. The person’s capacity to raise their arm over 90 degrees may be less compromised if the anterior belly is not torn as well as if the anterior fibers are protected.

During surgery, it is important to keep an eye on the two halves of the muscle and its structural integrity to better understand post-operative recovery and functional ability and to enable suitable rehabilitative measures.

Effective communication among all members of the healthcare team is essential to achieving the best possible results for a client with supraspinatus pathology.

For the best results, it is imperative to know which muscle is implicated in the disease, whether the rotator cuff interval is damaged or closed surgically, and whether the anterior fibers were engaged in the tear and repair.

Good team communication is essential for radiological detection, conservative therapy, surgical choices, and post-surgical rehabilitation.

Diagnosis

The humeral head may appear high-riding on anteroposterior projectional radiography of the shoulder, with an acromiohumeral distance of fewer than 7 millimeters (0.28 in).

Repair

According to one study, shoulder functioning can be improved by arthroscopic surgery for full-thickness supraspinatus injuries.

The University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center carried up a comparative effectiveness study of surgical and nonoperative treatments for rotator cuff injuries in 2010. A single study that found “Patients receiving early surgery had superior function compared with the delayed surgical group” was found during the review.

The review pointed out that the study’s significance level was not disclosed, and it decided not to include it in one of its conclusions. Rather, it came to the following conclusion: “Patients and providers must choose whether to attempt initial nonoperative management or proceed immediately with surgical intervention, so the lack of evidence regarding early versus delayed surgery is particularly concerning.”

Regarding surgical methods, research contrasting mattress locking and absorbable sutures, as well as single-row and double-row suture anchor fixation, did not disclose variations in cuff integrity or shoulder function. Patients who combined physical therapy and continuous passive motion showed a small postoperative advantage over those who just received physical therapy.

To properly compare the effects of operational versus nonoperative therapies, there is not enough evidence. Rarely were complications documented, or they weren’t thought to be clinically important.

Surgical intervention was strongly supported by a 2016 study assessing the efficacy of arthroscopic therapy of rotator cuff calcification. The general population’s shoulder pain is primarily caused by calcification of the supraspinatus tendon, which frequently gets worse after a supraspinatus tear.

The study’s findings showed that, after an average of 5.3 post-operative months, 95.8% of the patients were back to participating in sports and their previous level of functionality. With time, once the calcification was removed, there was a noticeable reduction in pain.

The research demonstrated the general efficacy of arthroscopic shoulder repairs as well as their low risk. Supraspinatus tendinitis should be checked out as the source of pain before surgery.

Paralysis

The suprascapular nerve which innervates the supraspinatus can be damaged along its course in fractures of the overlying clavicle, which can reduce the person’s ability to initiate the abduction

Other Issues

Situated between the supraspinatus and subscapularis tendons is the rotator cuff interval. According to research by Jost et al., the coracohumeral ligament, superior glenohumeral ligament, glenohumeral joint capsule, supraspinatus, and subscapularis make up this interval’s structure and function.

The interval was split into two parts: a 1-layer lateral component and a 3-layer fibrous plate.

The 1-layer lateral part mostly limits external rotation when the arm is adducted, while the 2-layer medial section was shown to limit inferior translation.

It was discovered that the crucial structure in the rotator cuff interval is the coracohumeral ligament component of the interval. It is essential for the glenohumeral joint’s stability, inferior translation, and external rotation.

An essential surgical factor is the rotator cuff interval and how it limits movement. The adducted joint’s resulting external rotation range is limited when the lateral portion of the gap is closed.

For proper functional return, the closure’s performance should therefore be in an externally rotated position.

Furthermore, to maintain the humeral head’s central location in the fossa, superior migration of the humerus as a result of rotator cuff rupture or insufficiency may necessitate the release of the medial coracohumeral ligament.

Release of the lateral aspect of the rotator cuff interval, leaving the coracohumeral ligament intact, may be an option in cases when the interval is constricted and restricting external rotation.

According to Lim et al., out of 99 subjects, 11 had pectoralis minor tendon inserted into the rotator cuff interval, and in 7 of the 11 subjects, the tendon was tethered to the retracted supraspinatus tendon.

This created tension on the tendon repair and necessitated a complete resection of the pectoralis minor tendon for the best possible outcome.

Test for Supraspinatus

The Full Can Test combined with the Empty Can Test is a standard orthopedic examination test for supraspinatus impingement or the integrity of the supraspinatus muscle and tendon. The test is frequently easier to take when sitting or standing.

One of the examiners on the side being evaluated stabilizes the shoulder girdle. The arm to be tested is brought into complete internal rotation with the thumb pointing down as if emptying a beverage can, and 90 degrees of abduction in the plane of the scapula (around 30 degrees of forward flexion).

The examiner’s other hand is pressing down on the superior portion of the distal forearm, but the patient resists.

The Empty Can Test should be used if there is severe discomfort and weakness.

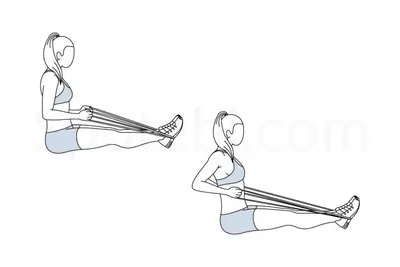

Exercise of Supraspinatus Muscle

Supraspinatus Muscle Stretching Exercise

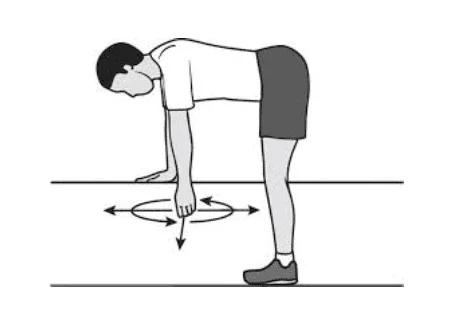

Pendulum Exercise

Place your left hand lightly on top of a bench, table, or other surface as you stand next to it for support.

Maintain a straight spine while bending forward at the waist.

Completely relax your right arm and shoulder, and let your right arm dangle freely in front of you.

Gently move your right arm in front of you and behind you, then side to side and in a circle.

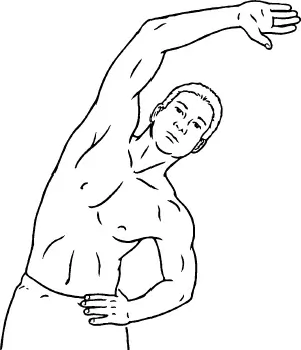

Single-side Stretch

Keep your arms at your sides in a comfortable position.

Try to put your left hand behind your back and grab your right wrist. If you are having trouble reaching it, place a towel over your left shoulder and use that to hold instead.

For increased tension, bend your head to the left and relax your neck as you use your right hand to grip your wrist or the towel behind your back.

Keeping your right shoulder relaxed, continue to grasp your wrist with the towel behind you from both ends. Then, using your left hand, pull your wrist or the towel up your back.

Before swapping sides, hold for 30 seconds and repeat up to four times.

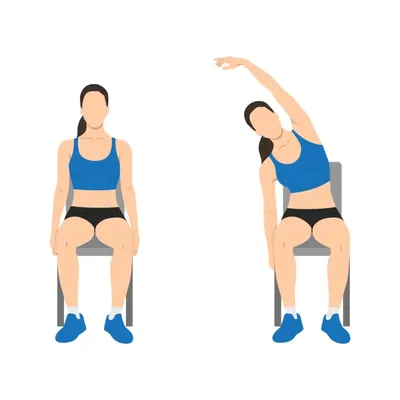

Seated Stretch

Take a seat on a sturdy bench or chair with a level surface.

Put your right arm in front of you with the elbow resting on your lower ribcage, bending it at a ninety-degree angle.

Raise your left hand to grasp your right thumb, then send your left upper arm beneath your right upper arm.

As you rotate your right arm out, gently draw your right thumb toward the right while letting your right arm and shoulder drop.

Before moving to the other shoulder, hold for up to 30 seconds, then let go for a little while and repeat up to four times.

Double Shoulder Stretch

Maintain a straight back while standing, then simultaneously extend your left and right shoulders by placing your hands on your hips, palms outward, and fingers pointing back.

Once you feel some tension behind your shoulders, steadily move your elbows forward while pressing the backs of your hands into your hips.

After up to 30 seconds of holding, relax and move your elbows back to their starting positions.

Repeat four times maximum.

Supraspinatus Muscle Strengthening Exercise

Prone External Rotation

The patient must lie on their stomach and hang their left upper arm at shoulder level, halfway off the side of a bed or bench, in order to perform this exercise.

With the left hand, grasp a one- to two-pound weight. Rotate the hand and forearm upward until the forearm is parallel to the floor.

Return to the starting position after holding this posture for two to four seconds.

Once you’ve completed 10 reps, switch to the right arm and repeat the workout.

This exercise helps to improve shoulder posture and strengthens the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles.

Resisted External Rotation

You have to stand with your left side facing a door to complete this workout.

Hold the other end of a resistance band in your right hand while the other end is fastened to the door handle.

Maintain the right elbow firmly resting against the side and flexed up to a ninety-degree angle.

As much as possible, rotate the right forearm away from the door without rotating the torso.

Contract your shoulder blades down and back as you work on this.

Keep the elbow on the side at all times.

Release the shoulder blade and rotate the forearm back to the beginning position after holding it for two to four seconds.

Repeat ten times before switching to the opposite side.

Prone Elevation

In order to complete this exercise, you must lie on your stomach and hang your right arm over the edge of a bed.

With your left hand, hold a one to two-pound weight.

Raise the arm slightly beyond ear level until it is even with the bed, with the left thumb pointing skyward.

As you execute, avoid lifting your shoulder off the bed or shrugging it.

For two to four seconds, hold the left arm in this position before lowering it again.

Repeat this with your right arm ten times through.

Side-Lying External Rotation

You must lie on your right side with your hand pressing against your abdomen and your left elbow bent at a 90-degree angle in order to do this exercise.

Left hand: hold a two-pound weight.

Lower and retract your left shoulder blade. Once the forearm is straight up and down, rotate the left palm and forearm away from the stomach.

After two to four seconds, hold this posture and slowly rotate the arm back to the belly.

Repeat with your right arm after ten repetitions.

Full Can

The patient must stand on one end of a resistance band and grasp the other end in their left hand to perform this workout.

In addition, the patient has the option to replace the resistance band with a 1- to 2-pound dumbbell.

Raise the arm at a 45-degree angle to the torso with the elbow extended and the thumb raised.

After the patient raises their arm just above the height of their ears, hold the position for one to two seconds before lowering it gradually back to the left side.

As you perform, don’t provide a shoulder shrug.

Perform the exercise again on the right side after ten repetitions.

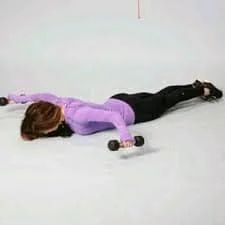

Prone Full Can Raise

You must lie flat on your stomach on a bench or bed in order to perform this workout.

Start with the palms facing forward and the arms pointing down toward the floor, slightly ahead of rather than directly below the shoulders.

Raise the arms straight out to the side until they are roughly shoulder height, then progressively lower them.

The prone full can, often referred to as the shoulder T or horizontal abduction in external rotation, is designed to offer dynamic stability, ideal muscle length and tension, and appropriate placement of the shoulder girdle and scapula.

T-Band Rows

You must encircle a pole or any other stable object at the belly button level with a band in order to do this exercise.

Hold onto the band’s ends to ensure that it is the same length on both sides while keeping the band taut where it was initially.

Start with your elbows extended and your trunk straight (which you should maintain the entire time). Then, take your elbows back straight while maintaining them tucked in.

Hold the band beside you and pinch the shoulders.

Try contracting a pencil by putting it between your shoulder blades.

Incline Reverse Lateral Dumbbell Raise Exercise

You must lie face down on an inclined bench in order to perform this exercise.

With both hands, hold a dumbbell below the chest while keeping your arms fully extended.

Lift the weights to shoulder height while separating them with an arc.

Go back to your initial position.

Conclusion

Maintaining the strength and flexibility of the supraspinatus muscle should never be undervalued. The strength, stability, and mobility of the shoulder are all dependent on this muscle. Stretching regularly can help lower the chance of shoulder injury or soreness. It’s critical to strike the ideal balance between getting a decent stretch and avoiding overstretching when reaching this muscle.

It’s crucial to get advice from a trained expert to determine the precise stretches and frequency that would work best for your particular requirements. Stretching can help you maintain your supraspinatus muscle’s health and pain-free function as part of regular physical activity.

FAQ

What causes pain in the supraspinatus muscle?

Overuse is the main factor that causes supraspinatus tendinopathy, as was previously mentioned. Individuals with the disorder may have increasing subdeltoid pain, which is exacerbated by prolonged overhead activity, elevation, or abduction. In addition, there could be soreness and a burning feeling in the shoulder region.

Where is supraspinatus located?

Supraspinatus extends from the supraspinous fossa of the scapula to the proximal humerus and is situated deep to the trapezius muscle in the posterior scapular area. Supraspinatus, in conjunction with the other rotator cuff muscles, stabilizes the glenohumeral (shoulder) joint when the upper limb is in motion.

What is physical therapy for supraspinatus?

The isotonic resistance exercises that are utilized to strengthen the scapular stabilizers include supraspinatus, internal rotators, external rotators, prone extension, horizontal abduction, forward flexion to 90°, upright abduction to 90°, shoulder shrugs, rows, push-ups, press-ups, and pull-downs.

What is the function of the supraspinatus muscle?

Supraspinatus, a component of the Rotator Cuff, aids in defying the forces of gravity that draw the upper limb’s weight downward at the shoulder joint. Maintaining the humerus’ head firmly placed medially on the scapula’s glenoid fossa aids in stabilizing the shoulder joint as well.

Where does supraspinatus attach?

One intrinsic muscle in the shoulder region is the supraspinatus. It belongs to the muscular group of the rotator cuff. Attachments: connects to the larger tubercle of the humerus after emerging from the supraspinous fossa of the scapula. The suprascapular nerve is innervated.

What is a nerve block for supraspinatus?

One safe and efficient way to manage pain in chronic shoulder illnesses is with suprascapular nerve block (SSNB). The procedure involves sitting the patient down and placing their upper limbs next to their body while an anesthetic is injected into the supraspinatus fossa of the afflicted shoulder.

How do you protect your supraspinatus?

Work Out Your Shoulders

Maintain Proper Posture.

Steer clear of repetitive motions overhead.

Take Shoulder Pain Seriously.

Take Care for Your Rotator Cuff Injuries.

Where do supraspinatus muscles come from?

The concave region at the top of the scapula, known as the supraspinous fossa or shoulder blade, is where this muscle begins. The supraspinatus muscle extends outward from the scapula to attach to the larger tubercle of the humerus, the long bone of the upper extremity.

How is supraspinatus treated?

Treatment options for a supraspinatus tear include medication, physical therapy, injections of steroids, and surgery. Anti-inflammatory and painkilling medications may be prescribed to treat shoulder swelling. Physical therapy includes instruction on exercises that help you strengthen and regain your shoulder’s flexibility.

What is the supraspinatus muscle structure?

One of the musculotendinous support structures that envelops and encircles the shoulder is the supraspinatus muscle, often known as the rotator cuff. It assists in mitigating the inferior gravitational pressures exerted on the shoulder joint as a result of the upper limb’s downward pull.

7 Comments