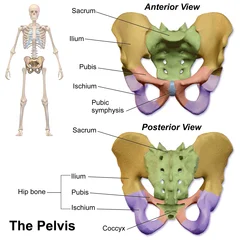

Pubic Symphysis

The pubic symphysis is a cartilaginous joint located between the left and right pubic bones of the pelvis. It provides stability while allowing slight movement to accommodate activities such as walking and childbirth. The joint is reinforced by strong ligaments and contains a fibrocartilaginous disc that helps absorb shock.

Introduction

The hip bones’ left and right superior rami of the pubis form a secondary cartilaginous joint called the pubic symphysis (plural: symphyses). It is located beneath and in front of the bladder. The pubic symphysis is where the penis’ suspensory ligament connects in males.

The suspensory ligament of the clitoris is where the pubic symphysis is connected in females. Most people can rotate it by one degree and move it about two millimeters. For women, this rises when they give birth.

The Greek word symphysis, which means “growing together,” is where the name originates.

Biomechanics

The pubic symphysis is exposed to several forces during daily activities. These include shearing and compression during single-leg stance, compression during sitting, traction on the inferior portion of the joint, and compression of the superior region during standing (Meissner et al. 1996). Despite its high resistance to separation, the healthy joint may occasionally burst during childbirth (Boland, 1933).

It is not surprising that not many biomechanical studies have been conducted given the location of this joint. Furthermore, it is challenging to compare various studies due to the inconsistent methodology. Steel pins were placed into the superior pubic ramus on either side of the symphysis in a study involving 15 healthy young adults (six men, six nulliparous women, and three multiparous women). Movement in certain postures and vertical and sagittal movements were measured (Walheim et al. 1984).

The anteroposterior sagittal movements were similar in both sexes at about 0.6 mm but larger (up to 1.3 mm) in multiparous women as a result of the joint’s morphology. The mean lateral movement of each pin was 0.5 mm for men and 0.9 mm for women when they were in the supine position with their hips flexed 90° and maximally abducted. When standing on alternate legs, the contralateral side pin’s mean vertical descent was 2.1 mm for multiparous women, 1.3 mm for nulliparous women, and 1 mm for men.

The direction of maximum symphyseal movement was noted. In a follow-up experimental investigation using ten new cadavers, Meissner et al. (1996) calculated that 120 N in the vertical direction and 68 N in the sagittal direction would be needed to generate such joint movements. When multiparous women’s mobility was at its highest, radiographic studies revealed similar values for vertical shift at the pubic symphysis (Garras et al. 2008).

In healthy young adults, rotation at the pubic symphysis was also examined by Walheim et al. (1984). The joint rotated less than 1° in both a sagittal plane about a horizontal axis and a coronal plane about a sagittal axis. Another study of two healthy young adults, a male, and a multiparous female, found that the young woman rotated up to 2° in the sagittal plane and up to 3° in the coronal plane at various points after steel pins were inserted and tantalum balls were implanted into her pubic bone (Walheim & Selvik, 1984).

Four groups of adult cadavers were used in one poorly documented study to test the strength of the pubic ligaments: males, nulliparous females, non-pregnant multiparous females, and, somewhat unsettlingly, primigravidae in the final trimester of pregnancy (Ibrahim & El-Sherbini, 1961). It was established how much force was needed to rupture the remaining pubic ligament in each group after one was left intact and the others were divided.

Before the inferior and superior ligaments, the anterior ligament was the strongest. For the posterior pubic ligament, no information was given. Each ligament exhibited the same pattern in the final trimester of pregnancy: it was weakest in primigravidae, slightly stronger in nulliparous compared to multiparous women, and strongest in men (Ibrahim & El-Sherbini, 1961).

These studies’ data suggest that the pubic symphysis can experience small-magnitude, multidirectional movements, with slightly larger ranges possible in postpartum women.

Structure

The pubic symphysis is an amphiarthrodial joint that is not synovial. It is 3 to 5 mm wider at the front of the pubic symphysis than it is at the rear. This joint is made of fibrocartilage and may have a cavity filled with fluid. The core of the joint is avascular, which could be caused by the compressive forces that travel through it and result in dangerous vascular disease. Attached to the fibrocartilage is a thin layer of hyaline cartilage that covers the ends of both pubic bones. Numerous ligaments support the fibrocartilaginous disk. These ligaments adhere to the fibrocartilaginous disk until fibers start to mingle with it.

These ligaments are weaker than the anterior and posterior ligaments, but the superior and inferior pubic ligaments offer the greatest stability. The tendons of the abdominal external oblique muscle, the rectus abdominis muscle, the gracilis muscle, and the hip muscles all support the sturdy and thicker superior ligament. The superior pubic ligament joins together the two pubic bones superiorly, reaching laterally as far as the pubic tubercles.

A thick, triangular arch of ligamentous fibers, the inferior ligament in the pubic arch is also referred to as the arcuate pubic ligament or subpubic ligament. It forms the upper border of the pubic arch and connects the two pubic bones below. Below, it is free and separated from the fascia of the urogenital diaphragm by an opening through which the deep dorsal vein of the penis enters the pelvis. Above, it is merged with the interpubic fibrocartilaginous lamina; laterally, it is joined to the inferior rami of the pubic bones.

Fibrocartilage

Small, linked bundles of thick, well-defined type I collagen fibers make up fibrocartilage. These bundles of fibrous connective tissue include cartilage cells, which are somewhat similar to tendon cells. Normally, the collagenous fibers are arranged in a systematic pattern parallel to the tissue’s tension. It has a modest quantity of glycosaminoglycans (2% of dry weight).

Consisting of repeating disaccharide units, glycosaminoglycans are long, unbranched polysaccharides that are relatively complex carbohydrates. There is no perichondrium around fibrocartilage. The perichondrium, which has a layer of thick, asymmetrical connective tissue and aids in cartilage formation and repair, envelops the cartilage of growing bone.

Hyaline cartilage

The white, glossy gristle at the end of long bones is called hyaline cartilage. Attempts to encourage this cartilage to mend itself often result in a similar but inferior fibrocartilage because of its low capacity for healing.

Development

The newborn’s symphysis pubis has thick cartilaginous end plates and is 9 to 10 mm in breadth. The adult size is attained by the middle of adolescence. As the organism reaches adulthood, its end plates get thinner. The symphysis pubis degenerates with age and after giving birth. The pubic disc is thicker in women, which permits the pelvic bones to move more freely, increasing the pelvic cavity’s diameter during birthing.

Articular surfaces

The pubic bones have oval, slightly convex articular surfaces that run posteroinferiorly in a craniocaudal direction and are oriented obliquely in the sagittal plane (Knox, 1831; Luschka, 1864; Fick, 1904; Testut & Latarjet, 1928). According to Testut and Latarjet (1928), the articular surfaces’ mean length is between 30 and 35 mm, and their mean width is between 10 and 12 mm.

Although the surfaces are parallel on the back, they typically diverge on the front, top, and bottom (Aeby, 1858; Fick, 1904). Most adult men have the pubic symphysis’s upper and lower borders at the same horizontal level, but 16% of the upper margins and 5% of the lower margins were uneven in a random sample of adult women of unknown parity (Vix & Ryu, 1971).

Hyaline cartilage covers the articular surfaces and ranges in thickness from 1 to 3 mm (Aeby, 1858; Luschka, 1864; Fick, 1904; Frazer, 1920; Sutro, 1936; Frick et al. 1991). However, Gamble et al. (1986) reported that the hyaline cartilage was only 200–400 μm thick in adults. As people aged, their hyaline cartilage became thinner, according to Loeschcke (1912).

In young adults, the subchondral bony surfaces are irregular (Luschka, 1864; Fick, 1904), but they become smoother and straighter on radiography around the age of 30 (Todd, 1930). Degenerative changes, such as joint narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and irregularity, begin to appear around the age of six (Todd, 1930). According to Todd (1920), Gilbert and McKern (1973), Brooks and Suchey (1990), and White and Folkens (2005), biological anthropologists use these characteristics to help determine age and sex.

According to Putschar (1976), 8–12 subchondral transverse bony ridges were present in young people, but by the time they were 25 years old, they had progressively vanished. According to Sutro’s (1936) radiographic analysis of cadavers, the subchondral bone became more porous after the age of fifty.

There is no evidence of bony fusion of the pubic symphysis in healthy adult humans, but it has been reported in some adult primates, including the red-leaf monkey (Presbytis rubicunda) (Tague, 1993).

Ligaments

Although the pubic symphysis is reinforced by four ligaments, Terminologia Anatomica only lists the superior and inferior pubic ligaments (Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology, 1998).

Superior pubic ligament

The pubic crest is connected to the superior pubic ligament as far laterally as the pubic tubercles, which spans the superior margins of the joint (Fick, 1904; Gamble et al., 1986). According to various descriptions, this ligament is connected to the pectineal ligament (Fick, 1904), the linea alba (Luschka, 1864; Testut & Latarjet, 1928), the interpubic disc (Testut & Latarjet, 1928; Frick et al. 1991), and the periosteum of the superior pubic ramus (Frick et al. 1991).

Although early reports noted a yellowish color (Fick, 1904; Testut & Latarjet, 1928), indicating the possibility of elastic fibers, Luschka (1864) claimed that the ligament was made up of irregular fibrous tissue. There is disagreement regarding the ligament’s strength and importance; some contend that it is crucial for strengthening the joint (Luschka, 1864), while others maintain that it has no functional significance (Rosse & Gaddum-Rosse, 1997).

Inferior pubic ligament

The inferior pubic ligament spans the inferior pubic rami in an arch (Fick, 1904; Frazer, 1920; Rosse & Gaddum-Rosse, 1997) and is also known as the subpubic (Gray, 1858; Frazer, 1920) or arcuate (Frick et al. 1991; Standring, 2008) pubic ligament. Its upper fibers are short and transverse, blending with the posterior pubic ligament (Luschka, 1864; Fick, 1904) and interpubic disc (Gray, 1858; Testut & Latarjet, 1928; Frick et al. 1991). Only its inferior fibers are connected to the inferior pubic rami, according to Luschka (1864) and Testut & Latarjet (1928).

According to reports, the inferior pubic ligament is stronger than the superior one (Knox, 1831; Testut & Latarjet, 1928), and it has once more been noted to have a yellowish appearance (Knox, 1831; Gray, 1858). There aren’t many quantitative studies on the ligament. With a height of 10–12 mm for both sexes, its maximum width has been measured to be 25 mm for men and 35 mm for women (Fick, 1904; Testut & Latarjet, 1928). The deep dorsal vein of the clitoris, or penis, is transmitted through a tiny opening between the anterior margin of the perineal membrane and its sharp inferior edge (Fick, 1904; Standring, 2008).

Anterior pubic ligament

The pubic bones are joined anteriorly by the anterior pubic ligament, which laterally combines with their periosteum (Knox, 1831; Luschka, 1864; Fick, 1904). According to reports, this ligament is a thick, resilient structure that is second only to the interpubic disc in preserving the pubic symphysis’ stability (Fick, 1904; Testut & Latarjet, 1928). It is made up of multiple layers of collagen fibers with different orientations. The deeper layers are more transversely aligned (Knox, 1831; Gray, 1858; Testut & Latarjet, 1928) and may blend with the interpubic disc (Aeby, 1858; Sutro, 1936).

On the other hand, the more superficial layers cross obliquely, connecting with the tendinous insertions of the pyramidal (Fick, 1904; Testut & Latarjet, 1928) and the rectus abdominis and oblique abdominal muscles (Gray, 1858; Luschka, 1864; Gamble et al., 1986). The tendinous insertions of the adductor muscles, namely the adductor longus, adductor brevis, and gracilis, have also been reported by several authors to contribute to the anterior pubic ligament (Luschka, 1864; Fick, 1904; Testut & Latarjet, 1928). The ligament’s vertical fibers that connect to the corpora cavernosa and ischiocavernosus muscles were only observed by Testut & Latarjet (1928).

The rectus abdominis and adductor longus muscles were consistently connected to the anterior pubic ligament and interpubic disc, according to Robinson et al.’s 2007 microdissection research of 17 old cadavers. There were both tendinous and muscular attachments to the adductor longus in nine of the specimens, while only muscle fibers were present in the other eight. Seven specimens had the adductor brevis muscle fibers blending with the anterior aspect of the pubic symphysis, but only one had the gracilis attached.

Anterior pubic ligament thickness has been reported to range from 5 to 12 mm on average (Aeby, 1858; Luschka, 1864; Fick, 1904; Testut & Latarjet, 1928). In 1904 and 1912, two authors referred to tiny perforating vessels in the ligament.

Posterior pubic ligament

The posterior pubic ligament, which spans the posterior aspect of the pubic symphysis and is thought to be composed of only a few thin fibers, is a relatively poorly understood structure (Aeby, 1858; Gray, 1858). Luschka (1864) said that this ligament blended with the pubic rami’s periosteum, but Testut & Latarjet (1928) were more explicit about where it was attached, mentioning the posterior edges of the pubic articular surfaces. There are oblique fibers that cross over and merge with the inferior pubic ligament and transverse fibers that blend with the superior pubic ligament (Luschka, 1864; Testut & Latarjet, 1928). In multiparous women, the ligament is thicker (Sutro, 1936; Putschar, 1976).

Blood supply and innervation

The blood supply and innervation of the pubic symphysis have not been extensively studied by authors. According to reports, a pubic branch of the obturator artery and a branch of the inferior epigastric artery supply blood to the joint. The medial circumflex femoral artery and branches of the external and internal pudendal arteries contribute less and vary more (Fick, 1904; Gamble et al., 1986). There are small blood vessels in the interpubic disc (Loeschcke, 1912), and as people age, they may become more noticeable (Putschar, 1976). The inferior epigastric arteries and pubic branches of the obturator supply an anastomotic arterial circle that vascularizes the interpubic ligaments and fibrous rim of the disc in rats (da Rocha & Chopard, 2004).

There are several different descriptions of the innervation of the joint, including branches of the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, and pudendal nerves (Standring, 2008) and the pudendal and genitofemoral nerves (Gamble et al., 1986). The innervation pattern and the branches that supply particular joint parts are not further explained, though.

Function

Your pelvis is strong enough to support your body and flexible enough to stretch during childbirth, thanks to the pubic symphysis, which connects your left and right abdominal bones. Each pelvic bone is connected to the others by a joint, making them nearly identical. The pelvic bones function in tandem to transfer weight from the upper body to the legs and feet.

You can rotate your pubic symphysis joint one degree and move it up to two millimeters. When you walk or run, this movement helps your pelvis absorb shock. This joint is particularly crucial during pregnancy. It becomes more flexible to allow for the widening of your pelvic bones and the passage of a baby through the birth canal.

Clinical significance

Injury

When the legs are stretched widely apart, the pubic symphysis slightly widens. These movements are frequently performed in sports, which increases the risk of a blockage of the pubic symphysis. In this scenario, the bones at the symphysis may not realign properly after the movement is finished, resulting in a dislocated position. The ensuing pain may be excruciating, particularly if the afflicted joint is subjected to additional strain. Most of the time, only a qualified medical practitioner can successfully reduce the joint to its normal position.

Disease

Widening is caused by metabolic disorders like renal osteodystrophy, whereas calcific deposits in the symphysis are the result of ochronosis. Inflammatory conditions like ankylosing spondylitis cause the symphysis to fuse bony. The most prevalent inflammatory condition in this region, osteitis pubis, is managed with rest and anti-inflammatory drugs. Symphysis degenerative joint disease, which can cause groin pain, is caused by instability or aberrant pelvic mechanics.

The symphysis slipping or separating is known as symphysiolysis. It is thought to happen in 0.2% of pregnancies.

Pregnancy

Human hormones like relaxin remodel this ligamentous capsule during pregnancy, making the pelvic bones more flexible for delivery. The symphysis pubis gap is normally 4–5 mm, but during pregnancy, it will increase by at least 2–3 mm. As a result, it is thought that a pregnant woman should have a total width of up to 9 mm between the two bones.

During childbirth, the symphysis pubis partially separates. This separation may develop into a diastasis of the symphysis pubis in certain females. The diastasis might be a prenatal condition, the result of a forceps delivery, or a result of a rapid birth. The cause of pelvic girdle pain (PGP) is a diastasis of the symphysis pubis. In total, PGP affects roughly 45% of pregnant women and 25% of postpartum women.

Symphysiotomy

A symphysiotomy is a surgical procedure used to widen the pelvis and enable childbirth in cases of mechanical issues. It involves dividing the cartilage of the pubic symphysis. When a cesarean section is not an option, it enables the safe delivery of the fetus. For women in remote locations who are having obstructed labor and no other medical intervention is available, symphysiotomy is advised.

Before the Caesarean section was invented, this procedure was used in Europe. In the past, the fetus’s skull was also, at least sometimes, crushed during obstructed labor to aid in the delivery process.

FAQs

Do fibrous joints make up the pubic symphysis?

One of the secondary cartilaginous joints situated in the midline between the pubic bone bodies is the pubic symphysis. The interpubic disc’s fibrocartilage and the surrounding ligaments form a robust fibrous sheet that makes up the symphysis.

Does pubic symphysis exist?

The connection at the front of the pelvis that joins the left and right pelvic bones is called the pubic symphysis. Between the pubic bones lies a fibrocartilaginous disc that makes up this structure.

Why does the pubic symphysis separate?

The pubic joint dislocates with a diastasis or separation. This can also occur as a result of a fall, a motor vehicle accident, a sports injury, or the stress of childbirth, as well as hormonal changes and pressure during pregnancy.

What feature distinguishes pubic symphysis?

A fibrocartilaginous joint, or symphysis, is a joint where the physis of one bone joins the body of another. Fibrocartilage is a constituent tissue of all but one of the symphyses, which are located in the vertebral (spinal) column.

How big is the pubic symphysis normally?

The pubic symphysis’s breadth varies with age. A newborn’s is 9–10 mm, and as they become older, they gradually lose it. In adults, the pubic symphysis typically measures 3–6 mm in width, with the anterior portion being larger than the posterior.

What is discomfort from the pubic symphysis?

Pregnant women may experience pelvic pain. This is sometimes referred to as symphysis pubis dysfunction (SPD) or pregnancy-related pelvic girdle discomfort (PGP). PGP is a group of painful symptoms caused by either your pelvic joints moving unevenly in the front or back of your pelvis or by your pelvic joints becoming tight.

References

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024, April 2). Pubic symphysis. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pubic_symphysis

- Professional, C. C. M. (2025, February 25). Pubic symphysis. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/23025-pubic-symphysis

- Pubic symphysis. (2023, October 30). Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/pubic-symphysis