PNF Technique

Introduction

Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation (PNF): The term Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation (PNF) refers to a therapeutic approach that involves stimulating proprioceptors (such as the muscle spindle and the Golgi tendon organs) in addition to other sensory stimuli (tactile, visual, or verbal) at the beginning (i.e., during the cognitive phase of motor learning) and gradually decreasing them as learning progresses.

The approach, which is based on the ICF model, aims to achieve the highest level of function possible.

It starts with the results of a clinical assessment to identify the major impairment of body structure or function (e.g., weakness) that may limit an activity (e.g., sitting to stand or walking) and restrict life participation (e.g., using transportation or a job), taking into account personal and environmental factors (e.g., age, fitness level, etc.) and environmental barriers (e.g. Subsequently, the therapist sets goals for treatment to address particular problems and

improve participation or activity.

PNF uses nerve impulses, such as spatial summary, temporal closing, and reciprocal inhibition, that have the neurophysiological ability to stimulate, inhibit, relax, or strengthen muscles. The methods, procedures, and tactics that make up the basis of PNF for recruiting those applicants will be explained on this page.

PNF basic principles

Principles are stimuli that are used in practice and can be either proprioceptive (e.g., resistance, traction, approximation, and stretching) or exteroceptive (e.g., tactile, verbal/auditory, or visual). All PNF practices include principles, with minor modifications based on the condition of the patients and the goals of treatment.

Tactile stimulus: indicated by the appropriate hand placement and grip on the target body part by both therapists.

Verbal or auditory stimulus: This can be seen by a therapist giving the patient instructions on when and how to move. It could be feedback, action, or preparation.

Visual stimulus: this means that people can look as closely as they can to notice and follow the movement. This encourages feedback, affects head and body movements, and provides some muscles with reflexive feedback or facilitation.

Resistance: The therapist applies the ideal amount of resistance based on the patient’s capacity and the therapy objective. Different types of muscular contractions are produced by different resistance levels or intensities.

When the patient stabilizes the posture of the extremity without any opposition from the therapist, or when the therapist’s resistance is equal to the patient’s ability to overcome, isometric contractions take place.

When the patient’s capacity goes above or below short of the therapist’s resistance, accordingly, the patient experiences eccentric (isotonic) contractions.

Traction: the therapist’s extension of the trunk or an extremity; the action is carried out through to the conclusion of the pattern, if possible.

Approximation: is the compression of the trunk or extremities, usually completed close to the pattern’s conclusion.

Stretching: Starting with the pattern that opposes the target pattern and working your way towards it is logical since the stretch stimulus puts the target muscle in the ideal lengthening posture for promoting muscle contractions.

PNF procedures

Irradiation: expansion of the stimulus-induced nerve impulse response.

Reinforcement: The number and variety of stimuli that are applied will increase the muscle reaction, strengthening it.

Both the therapist’s shoulders and pelvis face the direction of motion, and the patient’s position is determined by the patient’s skills and the aims of the treatment.

Timing: Every pattern has a set motion sequence (timing) that can be altered to strengthen a specific muscle reaction (focus on time).

Patterns: Muscle synergy contractions produce 3D multiple joint movements, which combine typical functional movements. Each pattern in a joint movement has an opposite pattern; the two patterns combined make up a diagonal.

While the movement of the pattern begins with the most distal joints, patterns are named based on the movement of the proximal joints. This pattern appears in all patterns and indicates standard time; any modifications to this pattern occur as focus timing.

Patterns of extremities

Unilateral patterns: While the movement of the pattern begins with the most distal joints, patterns are named based on the movement of the proximal joints. This pattern appears in all patterns and indicates standard time; any modifications to this pattern occur as focus timing.

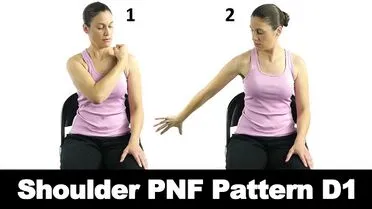

For upper extremities:

The first diagonal (D1): Flexion-adduction-external rotation pattern of the glenohumeral joint and Extension-abduction-internal rotation pattern of the glenohumeral joint.

The second diagonal (D2): The glenohumeral joint’s external rotation pattern, flexion-abduction, and internal rotation pattern, extension-adduction, make up the second diagonal (D2).

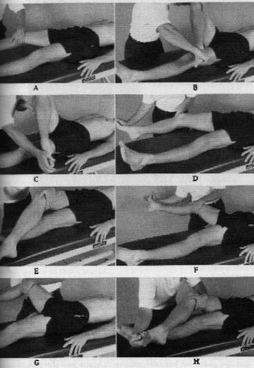

For lower extremities:

The first diagonal (D1): On the first diagonal (D1) rotation inside the abduction, the flexion-adduction-external rotation pattern and extension are displayed.

The second diagonal (D2): Flexion-abduction-internal rotation pattern and extension-adduction-external rotation.

It should be noted that each flexion pattern is accompanied by the extension of the toes + ankle dorsiflexion, and each extension pattern is accompanied by the flexion of the toes + ankle planterflexion. Moreover, subtalar motions depend on whether hip adduction or abduction is part of the intended pattern. Hip abduction is linked to subtalar eversion, while hip abduction is linked to subtalar inversion.

Patterns of scapula and pelvis

The closest points at which the extremities and trunk articulate in the human anatomy are called girdles. The scapulae connect the upper extremities to the trunk, while the pelvic girdles connect the lower extremities to the trunk. Girdle designs can be used either alone or in combination with trunk or upper extremity patterns.

Scapula

The two patterns that make Scapula D1 are the anterior elevation pattern, which pushes the scapula up and forward (a combination of upward rotation, abduction, and protraction), and the posterior depression pattern, which moves the scapula backward (a combination of downward rotation, adduction, and retraction).

Flexion-adduction-external rotation glenohumeral pattern causes anterior elevation, whereas the extension-abduction-internal rotation glenohumeral pattern causes posterior depression.

Scapula D2 makes up the anterior depression pattern, which brings the scapula down and in front, and the posterior elevation pattern, which pulls the scapula up towards the ear and back (a combination of upward rotation, adduction, and retraction).

Flexion-abduction-external rotation glenohumeral pattern causes posterior elevation, whereas the extension-adduction-internal rotation glenohumeral pattern causes anterior depression.

The scapula articulates with the thoracic cage and humerus, and the muscles of the scapula are connected to the spine and humerus. Because of this, movements of the upper limbs or trunk could be associated with movements of the scapula.

Pelvis

The anterior elevation pattern, in which one side of the pelvis moves forward and up towards the trunk, and the posterior depression pattern, in which one side of the pelvis moves backward and down, make up the Pelvis D1.

Pelvis D2 is made up of the anterior depression pattern, in which the pelvic side goes backward, and the posterior elevation pattern, in which one side of the pelvis moves forward and up towards the trunk.

Pelvic patterns, in opposition to scapular diagonals, do not directly correlate with patterns of the lower limbs since their motions are predominantly dependent on trunk muscle actions rather than lower extremity muscles.

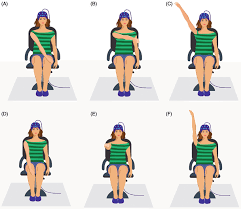

Bilateral patterns

If we wish to engage both the lower and upper extremities, we may use four main combinations:

Symmetrical: We give the person instructions to move both upper extremities in the same pattern, such as flexion-adduction-external rotation.

Asymmetrical: We instruct the learner to perform a specific diagonal pattern on one limb and a different pattern in the same direction as the first from the other diagonal on the other limb, for example, flexion abduction external rotation and flexion adduction external rotation.

Reciprocal symmetrical: For example, we train them to perform the flexion-adduction-internal rotation and extension pattern in one leg and the opposite pattern in the other limb from the same diagonal.-rotation inside the abduction.

Reciprocal asymmetrical: Flexion, adduction, and external rotation, as well as extension, and adduction, are examples of patterns the patient performs in one limb and opposes in the other.

Patterns of the trunk

Asymmetrical motions using bilateral extremities patterns are performed to initiate the rotation of the spine during trunk movements. Trunk movement patterns are limited to:

- Flexion with right rotation

- Extension with left rotation

- Flexion with left rotation

- Extension with right rotation

The lower trunk moves into flexion when the lower limbs move into flexion, and vice versa. However, when both upper and lower extremities move into flexion, this promotes upper trunk extension.

PNF techniques

Strengthening:

Rhythmic initiation: A succession of 1) initial passive, 2) active-assistive, and 3) active movement through the agonist pattern is known as rhythmic initiation.

Agonistic technique

contractions that are repeated, either from the start or all the way through.

Combinations of isotonic.

Replication.

Rhythmic stabilization: An isometric contraction of the agonist is followed by an isometric contraction of the antagonist to create rhythmic stabilization.

Antagonistic technique

Repeated contraction: an isotonic contraction against maximal resistance both concentrically and eccentrically throughout the range of motion.

Slow Reversal: The isotonic contraction of the agonist is followed right away by an isotonic contraction of the antagonist in a slow reversal.

Slow reversal-hold: an isotonic contraction of the agonist followed immediately by an isometric contraction.

Everyone can use rapid stretch to promote muscle activity.

Relax techniques:

Hold – relax.

Contract – Hold relax.

- Rhythmic Initiation: P-ROM, active-assisted, MRE

- Rhythmic Stabi1ization: “HOLD”

- Repeated Contraction: “PUSH/PULL” (INSERT QUICK-STRETCH)

- Slow reversal: “PUSH-PULL”

- Slow reversal-ho1d: “PUSH-HOLD, PULL-HOLD”

Stretching:

Contract relax: isotonic contraction of the antagonist followed by passive stretch

Hold-relax: isometric contraction of the agonist followed by passive stretch

Agonist contract-relax: The body part is moved actively in the agonist pattern via isotonic contraction of the agonist (active stretch).

Slow reversal-hold-relax: the antagonist contracts isotonically, then the agonist contracts isometrically, and finally there is a relaxation phase.

Stretching (hamstring stretching example)

Contract-Relax: PUSH through ROM, then RELAX

Agonist Contract-Relax: HOLD, PULL

Slow Roversal-Hold-Re1ax: PUSH, HOLD, PULL

Intended goals for using techniques:

Facilitating motion initiation

Rhythmic initiation

Repeated stretch from the beginning of the range.

Learning a motion

Rhythmic initiation

Combination of isotonic

Repeated contractions

Replication

Changing the rate of motion

Rhythmic initiation

Reversals

Repeated contractions

Increasing strength

Combination of isotonic

Reversals

Rhythmic stabilization

Repeated contractions

Increasing stability

Combination of isotonic

Reversals

Rhythmic stabilization

Increase coordination and control

Combination of isotonic

Rhythmic initiation

Reversals

Rhythmic stabilization

Repeated contractions

Replication

Increase endurance

Reversals

Rhythmic stabilization

Repeated contractions

Increase ROM

Reversals

Rhythmic stabilization

Repeated contractions

Contract–relax

Hold–relax

Relaxation

Rhythmic initiation

Rhythmic stabilization

Hold–relax

Decrease pain

Rhythmic stabilization

Reversals

Hold–relax

How does PNF help?

Every time the muscle is kept in place, it can adjust to its new position thanks to the progressive stretching and shift between contraction and relaxation. The following time, it can stretch even farther thanks to this. Gains in range of motion and flexibility are possible if this is done frequently.

Who benefits from PNF?

PNF is a useful treatment for those who are healing from muscle injury. In addition, it can aid in improving the range of motion and flexibility in healthy people. This can help the body function better during sports-related activities.

Contraindication

There aren’t many contraindications, however, the majority include severe cardiovascular conditions, metastasizing malignancies, and fever diseases.

Conclusion

To sum up, the Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation (PNF) approach is a very successful strategy for improving strength, flexibility, and functional movement patterns in sports medicine and rehabilitation. By combining principles of muscle contraction, stretching, and reflexes, PNF improves neuromuscular re-education and improves motor control and coordination.

Its adaptability and versatility make it appropriate for a wide range of populations and circumstances, from people looking to increase their range of motion and mobility to sportsmen recovering from injuries. Although more investigation is required to completely comprehend its workings and best uses, PNF is still a useful tool in the rehabilitation toolbox, providing a comprehensive method for maximizing and regaining physical function.

FAQ

What are 3 PNF techniques?

PNF stretches come in three distinct varieties: Contract-Release Approach. Contract-Agonist Approach. Method: Contract-Relax-Agonist-Contract.

What is the principle of the PNF technique?

For improving the range of motion, the PNF methods “hold–relax” and “contract-relax” are specifically employed. The idea behind hold-relax is to use the maximum relaxation that results from a maximal contraction to produce maximal relaxation in the tight muscle group that restricts the movement.

What is the PNF technique called?

Hold-relax. Hold-relax is the most often used PNF stretch technique.

Contract-relax. then relax. The contract-relax approach is another popular PNF technique.

Hold-relax-contract. A third PNF technique is the hold-relax-contract. …

Contract-relax-antagonist-contract (CRAC) …

Hold-relax-swing.

What is the pattern of the PNF technique?

PNF patterning, which is divided into D1 (Diagonal 1) and D2 (Diagonal 2) patterns, is employed for the upper and lower extremities. The upper extremity pattern includes the elbow, wrist, fingers, and shoulder. In contrast, the lower extremity pattern includes the hip, knee, ankle, and toes.

Who invented PNF?

PNF techniques were created by Dr. Herman Kabat, a physician and neurophysiologist, Sister Elizabeth Kenney, an Australian nurse who treated polio patients, Maggie Knott, PT, and Dorothy Voss.

References

- Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Proprioceptive_Neuromuscular_Facilitation

- PNF – WikiLectures. (n.d.). https://www.wikilectures.eu/w/PNF

2 Comments