Accessory Nerve (CN XI)

Introduction

The accessory nerve, also known as cranial nerve XI (CN XI), is one of the 12 cranial nerves in humans. It is considered a motor nerve and primarily innervates the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles, which play crucial roles in head and shoulder movements.

It has a cranial and a spinal component, though there is ongoing disagreement over whether the cranial component is a component of the vagus nerve or the SAN. The larynx, pharynx, and soft palate are innervated by the cranial part and cranial nerves 9 and 10.

It can be injured by daily movements or behaviours that exceed the nerve structure’s elastic capacity, such as excessive stretching or lifting heavy objects. These kinds of injuries are typically harmless. If the patient undergoes extensive tumour mass removal surgery in the neck area with a lack of blood nutrition or partial removal, the nerve may be severely injured. Its removal is necessary when necessary to transfer the cranial nerve where there is no electrical activity, compensate for a lesion to a peripheral nerve, and restore function to a limb.

Course of the Accessory Nerve

The accessory nerve is traditionally classified into spinal and cranial components.

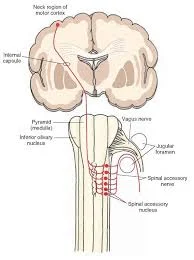

Spinal component

The spinal portion is formed by neurons in the upper spinal cord, specifically the C1-C5/C6 spinal nerve roots. These fibres combine to form the spinal part of the accessory nerve, which travels superiorly to enter the cranial cavity through the foramen magnum.

The nerve travels through the posterior cranial fossa to reach the jugular foramen. It briefly intersects the cranial portion of the accessory nerve before leaving the skull (along with the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves).

The spinal portion innervates the sternocleidomastoid muscle by descending along the internal carotid artery outside the cranium. After that, it passes through the neck’s posterior triangle, feeding the trapezius with motor fibres.

Cranial component

The cranial portion is much smaller and originates on the lateral side of the medulla oblongata. It exits the cranium through the jugular foramen, where it briefly contacts the spinal portion of the accessory nerve.

Immediately after leaving the skull, the cranial part connects with the vagus nerve (CN X) at the inferior ganglion. The fibres from the cranial part are then distributed via the vagus nerve. As a result, the cranial portion of the accessory nerve is considered a part of the vagus nerve.

Embryology

The XI nerve develops embryologically from the same ganglionic crest (ectoderm) as the vagus nerve. The structure contains both motor and sensitive components. The caudal termination gains more motor functions and the cranial termination becomes more sensitive as development advances.

The ganglion crest lateralizes and splits into the right and left sections after about 20 days; the caudal part of the crest produces a band of fibres that will eventually become the accessory nerve. This fibre band is located at the fourth, fifth, and sixth cervical segments.

During the fourth week, it separates from the vagus nerve and enters a mesodermal mass that will become the sternocleidomastoid muscle. At the end of the fifth week of gestation, the nerve is medial to the dorsal rootlets and connects to what will become the spinal cord at irregular intervals. It connects to the first spinal ganglion.

The cranial portion is a row of ganglia that forms the nerve. During development, the ganglia become larger and connect to the vagus nerve’s jugular ganglion.

During the second and third months, the XI nerve stretches and forms its final shape.

Blood Supply and Lymphatic

The proximal, distal, and recurrent branches of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery supply blood to the nerve’s intracranial portion. The musculospiral artery of the ascending pharyngeal artery and collaterals of the anterior spinal artery both affect the nerve’s spinal roots.

The occipital artery and lingual artery branches supply blood to the extracranial portion.

Lymphatic nodes follow the nerve’s extracranial path at the level of the neck’s posterior triangle, while the venous system follows the nerve’s entire path with small veins that affect the external jugular vein.

Nerves

There is an anastomosis between the accessory nerve and the root of C1 (some texts refer to C2-C3). There is an interesting anastomosis between the stellate ganglion and the IX, but its function is unknown.

It also communicates with a branch of the big auricular nerve as it exits the jugular foramen. The XI has an anastomosis with the vagus (Lobstein anastomoses) near the upper edge of C1’s transverse process.

The function of Accessory Nerve

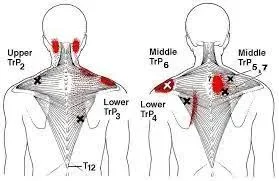

The spinal component of the accessory nerve controls the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. The trapezius muscle is responsible for shrugging the shoulders, while the sternocleidomastoid is in charge of turning the head. The trapezius muscle, like most others, is controlled from the opposite side of the brain. Contraction of the upper trapezius muscle raises the scapula.

However, the nerve fibres that supply the sternocleidomastoid are thought to change sides (Latin: decussate) twice. This means that the sternocleidomastoid muscle is controlled by the brain on the same side of the body. Contraction of the sternocleidomastoid fibres causes the head to turn to the opposite side, indicating that the brain is receiving visual information from that area. In contrast, the cranial component of the accessory nerve controls the muscles of the soft palate, larynx, and pharynx.

Classification

Regarding the nomenclature used to characterise the data carried by the accessory nerve, researchers cannot agree. Some researchers hypothesise that the spinal accessory nerve innervating the pharyngeal arches must contain unique visceral efferent (SVE) information because the muscles that make up the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid originate from them.

This is in line with earlier findings that the nucleus ambiguus of the medulla and the spinal accessory nucleus appear to be continuous. Others believe the spinal accessory nerve transmits general somatic efferent (GSE) information. Others believe it is reasonable to conclude that the spinal accessory nerve includes both SVE and GSE components.

Clinical Importance of Accessory Nerve

Injury to the SAN causes varying degrees of dysfunction in the Trapezius and Sternocleidomastoid muscles.

The different causes of injury include:

- Neck Trauma

- Injuries to the arm or neck can result from surgical procedures like lymph node biopsy, parotid surgery, carotid surgery, and jugular vein cannulation.

- Radiation treatment for the lymph nodes in the neck

- Aneurysms of the internal carotid

- A fracture of the atlas bone or hyoid caused by direct trauma

- The following conditions may impair nerve function: Pharyngo-cervical-brachial variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome, Sandifer syndrome, Eagle syndrome, Diphtheria (infection), Poliomyelitis or Tetanus (both of which rarely affect the XI nerve), botulism, and sarcoidosis. Other causes include diabetes, vitamin B12 deficiency, and tumours.

Assessment of Accessory Nerve

A thorough medical and objective history should be conducted to determine the cause and extent of the damage.

- Imaging tests such as EMG are often ordered.

- Watch for muscle wasting.

- Look for lateral winging of the scapula.

- Check the range of motion of the Trapezius and Sternocleidomastoid muscles.

- Muscle testing of the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid is essential.

Treatment

Physical Therapy Treatment

Traditional physiotherapy methods are the primary mode of treatment. This focuses on restoring function to the shoulder girdle, specifically the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. Methods used may include:

- Taping, for example, McConnell taping to facilitate trapezius action.

- Some studies have found that using acute brief low-frequency electrostimulation, such as TENS, can help with axonal growth.

- Using a sling for several hours a day can help manage pain.

- Cervical PNF patterns extend to flexion with rotation, while Scapular PNF patterns range from anterior depression to posterior elevation.

- Hydrotherapy Programme

- Strengthening exercises for the entire shoulder girdle, with a focus on the trapezius and SCM.

- Stretching and proprioceptive training are recommended for shoulder and neck muscles, nerves, and soft tissues.

- Personalised home exercise programme

Surgical Intervention.

If physiotherapy is not effective, other options are considered, including

- Nerve surgery, grafting, and regeneration

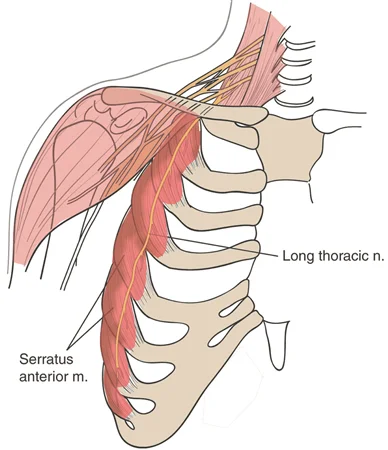

- Muscle transfers to stabilise the scapula, such as in the modified Eden Lange technique of scapulothoracic fusion

Neural regeneration, nerve grafting, and nerve surgery are available surgical options. Other treatment options include tendon or muscle transfer to stabilise the scapula for patients who do not respond to nerve repair or surgery. Scapulothoracic fusion is a widely used surgical procedure.

Summary

The accessory nerve is the eleventh paired cranial nerve, serving a somatic motor function by innervating the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. It has a cranial and spinal component, with ongoing disagreement over whether it is part of the vagus nerve or the SAN. The larynx, pharynx, and soft palate are innervated by the cranial part and cranial nerves 9 and 10.

The accessory nerve is traditionally classified into spinal and cranial components. The spinal portion is formed by neurons in the upper spinal cord, specifically the C1-C5/C6 spinal nerve roots, which combine to form the spinal part of the accessory nerve. The cranial component is smaller and originates on the lateral side of the medulla oblongata. It exits the cranium through the jugular foramen, briefly contacts the spinal portion of the accessory nerve, and then connects with the vagus nerve (CN X) at the inferior ganglion.

The spinal component of the accessory nerve controls the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles, while the cranial component controls the muscles of the soft palate, larynx, and pharynx. Injury to the SAN causes varying degrees of dysfunction in the Trapezius and Sternocleidomastoid muscles.

Different causes of injury include neck trauma, radiation treatment for lymph nodes, aneurysms of the internal carotid, fractures of the atlas bone or hyoid caused by direct trauma, and conditions such as diabetes, vitamin B12 deficiency, and tumours.

FAQs

What is unique about the accessory nerve?

The sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles, which are supplied by this nerve, carry out the following tasks: head movement in the opposite direction of the sternocleidomastoid muscle contraction. Tilting the head towards the contracting sternocleidomastoid muscle.

What can cause damage to the accessory nerve?

The accessory nerve can be damaged accidentally, intentionally, or as a result of blunt trauma. This activity reviews nerve anatomy and describes how to evaluate and treat accessory nerve injury. It also emphasises the importance of interprofessional teams in managing this condition.

What’s another name for the accessory nerve?

The accessory nerve, also known as the eleventh cranial nerve, cranial nerve XI, or just CN XI, is a cranial nerve that supplies the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. It is classified as the eleventh of twelve pairs of cranial nerves because a portion of it was previously thought to originate in the brain.

What is the role of the accessory nerve in swallowing?

The cranial portion of the accessory nerve connects to the vagus nerve and moves some of the muscles in the soft palate, pharynx, and larynx. Those structures in the head and throat are responsible for eating, speaking, and breathing.

How do you identify accessory nerves?

The nerve’s primary identification point is Erb’s point, which is defined by the greater auricular nerve exiting behind the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

What happens if the accessory nerve becomes damaged?

Spinal accessory nerve injury can cause trapezius dysfunction. The trapezius is a major scapular stabiliser made up of three functional components. It helps with scapulothoracic rhythm by elevating, rotating, and retracting the scapula.

References

- Bordoni, B., Reed, R. R., Tadi, P., & Varacallo, M. (2023, July 17). Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 11 (Accessory). StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507722/

- The Accessory Nerve (CN XI) – Course – Motor – TeachMeAnatomy. (2023, October 12). TeachMeAnatomy. https://teachmeanatomy.info/head/cranial-nerves/accessory/

- Accessory nerve. (2024, May 4). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accessory_nerve

- Accessory Nerve Cranial Nerve 11. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Accessory_Nerve_Cranial_Nerve_11

- Physiotherapist, N. P. (2024, March 4). Spinal accessory nerve : origin, course & applied anatomy. Mobile Physiotherapy Clinic. https://mobilephysiotherapyclinic.in/spinal-accessory-nerve/

- Patel, M., & Wahba, M. (2009, September 16). Spinal accessory nerve. Radiopaedia.org. https://doi.org/10.53347/rid-7191

- Dellwo, A. (2023, July 17). The Anatomy of the Accessory Nerve. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/accessory-nerve-anatomy-4783765

One Comment