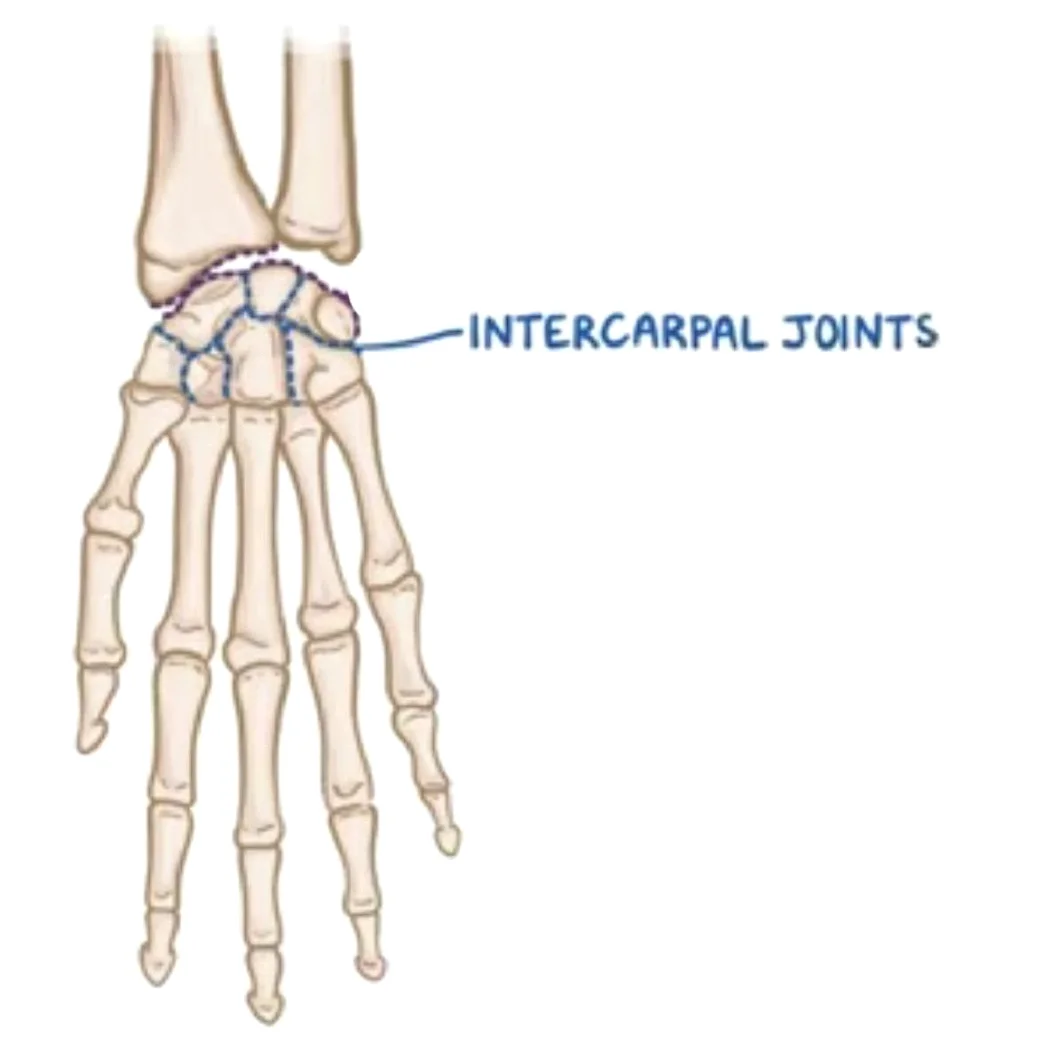

The intercarpal joints are synovial plane joints located between the carpal bones of the wrist. They allow for small gliding movements, contributing to the flexibility and overall motion of the wrist.

These joints are reinforced by ligaments, including the dorsal, palmar, and interosseous ligaments, which provide stability. The midcarpal joint, between the proximal and distal carpal rows, plays a key role in wrist movement, especially flexion and extension.

Introduction

The joints in the synovial plane that unite the carpal bones are called intercarpal joints. They assemble three joint sets;

- Proximal carpal row joints join neighboring surfaces of the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum bones. The pisiform joint, an articulation between the pisiform and triquetrum, is a part of the proximal carpal joints but is also referred to as a separate joint.

- The distal carpal row joints allow the neighboring surfaces of the hamate, capitate, trapezium, and trapezoid bones to articulate.

- The carpal rows articulate with one another through the midcarpal joint.

Little mobility occurs inside the proximal and distal carpal rows because they are held and anchored by several ligaments. They are responsible for coordinating the movements of the midcarpal and wrist (radiocarpal) joints. However, the midcarpal joint can create a considerable range of motion that is divided into two degrees of freedom: abduction-adduction and flexion-extension.

Articular surfaces

The articular surfaces of all intercarpal joints are functionally regarded as being almost flat and coated with fibrocartilage, making them all synovial plane joints. Thin fibrous capsules that have synovial membranes lining their interiors encircle the joints.

Scapholunate and lunotriquetral joints are formed by the proximal carpal row’s joints, which join the comparatively flat/planar neighboring surfaces of the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetral bones. The palmar surface of the triquetrum bone articulates with the pisiform bone, which is located within the tendon of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle, to form the pisiform joint. Additionally, the pisohamate and pisometacarpal ligaments connect the pisiform bone to the fifth metacarpal and hook of the hamate bones, respectively.

In the distal carpal row, the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate bones are joined by joints. The trapeziotrapezoid, trapezoid capitate, and capitohamate joints are formed by these articulations and are significantly less flexible than the proximal carpal row joints.

The compound articulation between the proximal and distal surfaces of the carpal bones is known as the midcarpal joint for short. More precisely, it is a joint that was created by the following:

- Proximally, the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetral bones

- Distally, the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate bones

There are two compartments in the midcarpal joint: the medial and lateral. Two articular areas are visible in the medial compartment. The convex surface of the capitate bone’s head, which is received by the concave distal surfaces of the scaphoid and lunate bones, forms the first.

The triquetrohamate component, the second half, is more complicated and has both concave and distally convex surfaces. The plane surfaces of the trapezium and trapezoid bones make up the lateral compartment, and they articulate with the scaphoid bone’s distally convex surface. This joint is hence a planosellar compound joint that is slightly convex distally.

Synovial membrane

The carpus’s wide synovial membrane encloses a highly irregularly shaped synovial cavity.

The upper part of the hollow sits between the upper surfaces of the second row of bones and the under surfaces of the navicular, lunate, and triangular bones.

It sends three prolongations downward between the four bones of the second row and two upward between the navicular and lunate and the lunate and triangular.

Due to the lack of the interosseous ligament, the prolongation between the greater and lesser multangulars, or between the lesser multangular and capitate, is frequently continuous with the cavity of the carpometacarpal joints, possibly of the second and third metacarpal bones, and occasionally of the fourth and fifth.

The latter condition is characterized by a distinct synovial membrane at the joint between the hamate and the fourth and fifth metacarpal bones.

The synovial spaces in these joints extend between the metacarpal bone bases for a brief distance.

The triangular and pisiform have different synovial membranes.

Ligaments and joint capsule

An uneven, two-layered joint capsule encloses the intercarpal and midcarpal joints. A synovial membrane that secretes synovial fluid, which keeps the joint lubricated, makes up the inner layer of the capsule, whilst fibrous connective tissue makes up the outside layer, giving the joint structural support. It connects the distal surfaces of the proximal carpus to the distal carpus’s proximal surfaces. Proximal projections across the scapholunate and lunotriquetral joints are another example of how it interdigitates between the bones.

Similarly, the capsule extends between the distal carpal row’s bones. There is frequent communication between the joint space of the corresponding carpometacarpal joint and the distal projection between the trapezium and trapezoid bones. Typically, the joint between the triquetrum and pisiform bones is isolated and has a synovial membrane lining its thin fibrous capsule.

Several ligaments support the joints of the carpal bones, including the palmar, dorsal, and interosseous intercarpal ligaments. It is important to note that there is some misunderstanding regarding the architecture of these ligaments because of the inconsistent descriptions found in the literature.

Both the palmar and dorsal intercarpal ligaments are attached to the carpal joint capsule; the palmar ligaments are significantly more numerous than the dorsum. On the other hand, the interosseous intercarpal ligaments are intracapsular. Moreover, the flexor retinaculum additionally supports the stability of the carpus.

Interosseous intercarpal ligaments

The scapholunate and lunotriquetral ligaments are the names of the interosseous ligaments of the proximal carpal row, which are called after the bones they connect. These structures separate the joint spaces of the midcarpal and radiocarpal joints by extending between the opposite surfaces of the relevant carpal bones.

In the distal row, the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate bones are connected by interosseous ligaments. They are composed of both deep and surface elements.

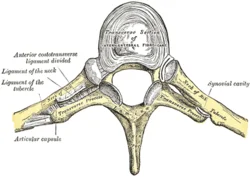

Dorsal intercarpal ligament

From the dorsal tubercle of the triquetrum bone to the dorsal groove of the scaphoid bone, the dorsal intercarpal ligament forms a horizontal strap. It may also transmit extra fibers to the trapezoid and capitate bones.

It makes up the floor of the wrist’s fourth and fifth dorsal (extensor) compartments. The dorsal scaphotriquetral ligament is the term used to describe the enlarged proximal portion of the dorsal intercarpal ligament that runs between the dorsal sides of the scaphoid and triquetrum bones.

Palmar intercarpal ligaments

The fan-shaped ligaments that comprise the palmar midcarpal ligaments are named after the bones they link. From radial to ulnar, they are as follows:

- The distal pole of the scaphoid bone is joined to the trapezium and trapezoid bones by the scaphotrapeziotrapezoidal ligament.

- The ligament known as the scaphocapitate runs from the scaphoid to the capitate bone.

- The triquetra capitate ligament connects the capitate bone’s body to the distal edge of the triquetrum.

- The triquetrohamate ligament, joins the hamate and triquetrum bones.

Flexor retinaculum

A fibrous band that runs across the anterior surface of the carpus is called the flexor retinaculum, or transverse carpal ligament. The retinaculum encloses the anterior/palmar concavity of the carpus into the carpal tunnel, which serves as a route for the tendons of the digital flexors and the median nerve.

The flexor retinaculum’s medial attachment lies on the pisiform and the hamate bone’s hook, but its lateral attachment is divided into superficial and deep laminae. While the deep lamina affixes to the medial lip of the groove on the medial aspect of the trapezium, the superficial lamina inserts into the tubercles of the scaphoid and trapezium bones.

The flexor carpi radialis tendon travels via a tunnel enclosed by this groove and the two laminae. The superficial surface of the retina is traversed by the ulnar artery and ulnar nerve. Guyon’s canal is a tube that encloses the superficial fibers of the retinaculum as they glide across the ulnar neurovasculature and adhere to the lateral face of the pisiform bone.

Innervation

The radial and median nerves, respectively, give rise to the anterior and posterior interosseous nerves, which innervate the intercarpal joints. These joints are additionally innervated by the dorsal and deep branches of the ulnar nerve.

Blood supply

The palmar and dorsal carpal arches, which are the anastomoses of the terminal branches of the ulnar and radial arteries, provide blood to the intercarpal joints.

Movements

A total of four articular surfaces are involved in the articulation of the hand and wrist:

- The inferior surfaces of the articular disk and radius;

- The superior surfaces of the triangular, lunate, and scaphoid, while the pisiform is not necessary for hand movement;

- The triangular, lunate, and scaphoid inferior surfaces that combine to form an S-shaped surface;

- The upper surfaces of the second row’s bones form a reciprocal surface.

Two joints are formed by these four surfaces: the wrist joint proper, which is proximal, and the mid-carpal joint, which is distal.

The motions of the radiocarpal joints are typically described in conjunction with those of the intercarpal and midcarpal joints, which follow their movements. There is minimal movement at the proximal and distal intercarpal joints because the carpus’ ligamentous structure firmly holds the bones together. The distal intercarpal joints move far less than the proximal ones, which provide notable flexion and extension. As the motions on the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints take place, these movements are crucial for modifying the hand’s morphology.

Keep in mind that the radiocarpal joint is a biaxial joint with two degrees of motion;

- Range of motion (ROM): 35° for flexion and 50° for extension

- RoM 8° abduction – RoM 15° adduction.

It is also feasible to combine the aforementioned actions to perform circumduction.

These motions on the radiocarpal joint are followed by minor movements on the midcarpal joint. The transverse and sagittal axes that go through the capitate bone’s head are where they occur. The following are the movements:

- When the wrist is flexed and extended, the hamate spins against the triquetrum, and the head of the capitate rotates against the nearby surfaces of the scaphoid and lunate.

- The proximal end of the capitate rotates laterally during wrist adduction, also known as ulnar deviation. The hamate rotates similarly, moving toward the lunate and dislodging it from the triquetrum bone.

- In abduction (radial deviation), the hamate and lunate are separated by the rotation of the proximal portion of the hamate towards the triquetrum.

The minor torsion movements between the carpal rows come after abduction and adduction. Abduction is characterized by the proximal row rotating in the opposite direction (pronation and flexion) and the distal row twisting in the direction of supination and extension. The proximal row spins in the direction of supination and extension during adduction, whereas the distal row twists in the direction of pronation and flexion.

As the hand is extended, the joint assumes a tightly packed configuration. The hand is in the open (resting) position when it is neutral or slightly flexed. In contrast to the midcarpal joint, which has equal limitations in flexion and extension, the capsular pattern has not been defined in the intercarpal joints.

The proximal and distal intercarpal joints allow any two adjacent bones to glide anteroposteriorly. Anteroposterior gliding between the proximal and distal rows of the carpus can also occur on the midcarpal joint.

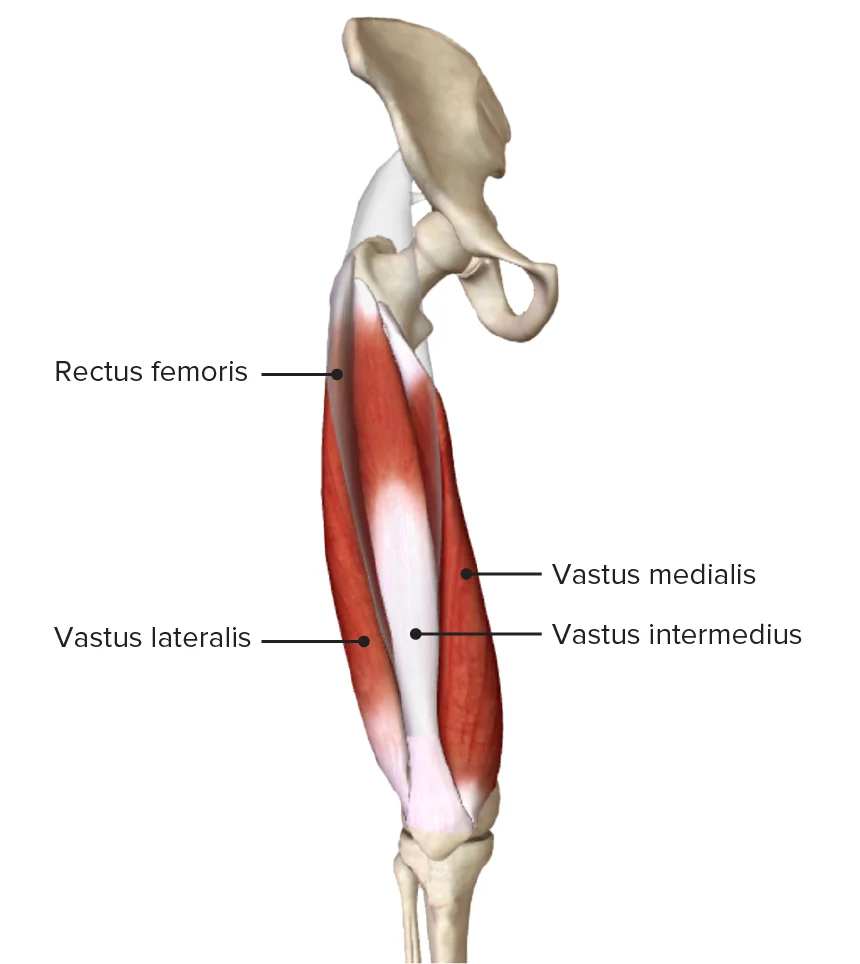

Muscles acting on the intercarpal joints

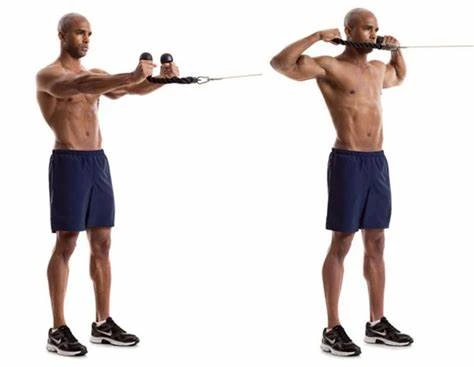

The muscles that move the radiocarpal (wrist) joint are the same muscles that move the intercarpal joints.

- The flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, and palmaris longus are the primary muscles involved in flexion. The flexor digitorum profundus, flexor digitorum superficialis, and flexor pollicis longus all aid in it.

- The digitorum, digiti minimi, indicis, and pollicis longus muscles support the primary extensors, which are the carpi radialis longus, brevis, and ulnaris.

- The carpi ulnaris flexor and extensor are the adductors.

- The flexor radialis, extensor radialis longus, and extensor radialis brevis are the main abductors. This movement uses the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis as accessory muscles.

Clinical signifiacnces

The wrist’s intercarpal joints are synovial plane joints that are situated in between the carpal bones. Small gliding motions are made possible by them, which enhance wrist motion and flexibility in general. Among their clinically significant aspects are:

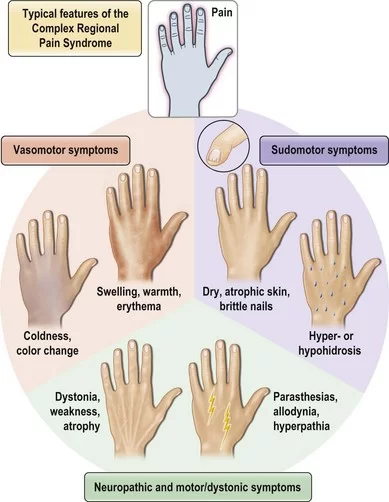

1. Arthritis (Osteoarthritis & Rheumatoid Arthritis)

- Reduced wrist mobility, pain, and stiffness can result from degenerative changes in the intercarpal joints, especially the scaphotrapeziotrapezoidal (STT) joint.

- The wrist joints are frequently impacted by rheumatoid arthritis (RA), which can cause progressive deformity.

2. Carpal Instability

- Scapholunate Dissociation: When the scapholunate ligament is damaged, the scaphoid and lunate bones become unstable, which impairs wrist function.

- Lunotriquetral Instability: Wrist pain and dysfunction may result from lunotriquetral ligament weakness or rupture.

3. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS) Relation

- CTS symptoms can be made worse by median nerve compression in the carpal tunnel, which can be caused by intercarpal joint swelling or degenerative changes.

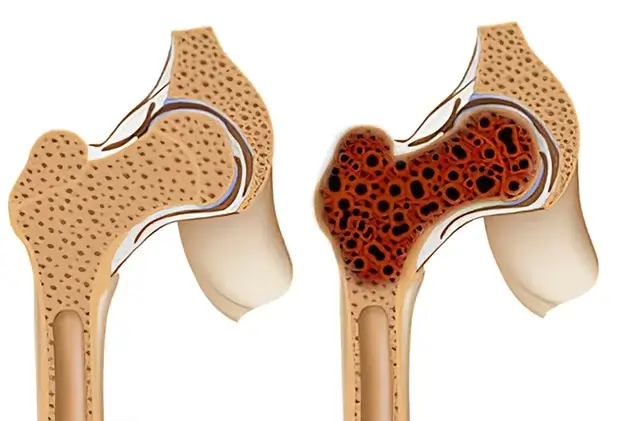

4. Kienböck’s Disease (Avascular Necrosis of the Lunate)

- When the lunate bone’s blood supply is disrupted, the midcarpal joint gradually collapses and develops arthritis.

5. Fractures & Post-Traumatic Arthritis

- Avascular necrosis or nonunion are common outcomes of scaphoid fractures, which impair intercarpal stability and cause post-traumatic arthritis.

- The integrity of the intercarpal joint can be seriously impacted by perilous dislocations.

6. Ganglion Cysts

- Intercarpal joints, especially the scapholunate joint, are frequently the source of these fluid-filled sacs, which can be uncomfortable or compress nerves.

7. Wrist Motion & Surgical Considerations

- The wrist’s flexion, extension, and circumduction are facilitated by the intercarpal joints.

- When intercarpal arthritis or instability is severe, proximal row carpectomy (PRC) may be necessary.

FAQs

What are the joints between the carpal bones?

The articular surfaces of all intercarpal joints are functionally regarded as being almost flat and lined with fibrocartilage, making them all synovial plane joints. The thin fibrous capsules that enclose the joints have synovial membranes lining their interior surfaces.

Does the intercarpal joint glide?

The hand contains multiple intercarpal joints, all of which fall under the category of sliding joints. Between bones that glide past one another along a plane formed by the flat sides of the bones where they articulate, there are sliding joints, also known as gliding joints.

Which intercarpal joint is the first?

The distal joint on the trapezium and the proximal joint facet of the first metacarpal combine to form the first carpometacarpal joint. The morphologic characteristics of these facets, in conjunction with a strong yet flexible joint capsule, provide the thumb with exceptional mobility and are crucial in thumb opposition.

What is the typical distance between the carpal bones?

There should be 1-2 mm between each carpal bone.

Which joint is the intercarpal?

There are three sets of joints, also known as articulations, that make up the intercarpal joints (joints of the wrist’s carpal bones): The carpal bones in the proximal and distal rows, as well as the two rows to one another, are among them. intercarpal joints.

Is there multiaxiality in the intercarpal joint?

Plane joints are multiaxial joints that only permit brief nonaxial gliding motions because their articular surfaces are nearly flat. The gliding joints that were previously discussed—the joints between vertebral articular processes and the intercarpal and intertarsal joints—are two examples.

What kind of movement takes place in the wrist’s intercarpal joint?

The wrist’s intercarpal joints are mainly used for gliding motions. Gliding motions happen when relatively flat bone surfaces pass one another. Very little rotation or angular movement of the bones results from this kind of motion.

What do the intercarpal and radiocarpal joints mean?

The intricate joint that joins the hand and forearm is the wrist. The intercarpal joints, which are tiny joints between the carpals, and the radiocarpal joint, which is located between the radius and the proximal row of the carpal bones (apart from the pisiform), make up this structure.

The intercarpal joint is what kind of joint?

An articulation between two flat bones of comparable size is called a planar joint, or gliding joint. Although multiaxial, planar joints are constrained by the surrounding ligaments. The acromioclavicular, intercarpal, and intertarsal joints are a few examples.

References

- Intercarpal joints. (2023, November 3). Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/intercarpal-joints

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024a, February 11). Intercarpal joints. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intercarpal_joints