Neck Muscles

Introduction

The neck muscles are a complex group of muscles that play a vital role in supporting and moving the head, maintaining posture, and facilitating respiration. They are categorized into several groups based on their location and function: the superficial muscles, the deep muscles, and the muscles of the suboccipital region.

The neck muscles extend from the base of the skull to the upper back and work together to bend the head and aid in breathing.

The neck muscles are Platysma, Sternocleidomastoid, Splenius capitis muscle, Longus capitis muscle, Longus colli muscle, Rectus capitis anterior, Rectus capitis lateralis, Scalanus anterior muscle, Scalanus medius muscle, and Scalanus posterior muscle.

Platysma

The platysma is a sheet-like muscle in the anterior neck’s subcutaneous tissue, which is superficial to the investing layer of deep cervical fascia.

Origin

It originates in the skin and fascia overlying the clavicle and runs superiorly along the neck.

Insertion

The platysma inserts into several points, including the mandible, lower facial skin, lower lip, and mouth corners.

Innervation

it is innervated by the facial nerve’s cervical branch (CN VII).

Blood supply

vascularized by the facial artery’s submental branch and the thyrocervical trunk’s suprascapular branch.

Function

The platysma primarily functions as a muscle of facial expression. For example, it aids in the expression of sadness by pulling the corners of the mouth inferiorly.

The sternocleidomastoid muscle

The sternocleidomastoid is a large, two-headed muscle in the neck.

Origin

Its clavicular head emerges from the medial third of the clavicle, while its sternal head emerges from the manubrium of the sternum.

Insertion

The heads come together and ascend diagonally to connect with the temporal bone’s mastoid process.

Innervation

The accessory nerve (CN XI) and the anterior rami of spinal nerves C2 and C3 innervate the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Blood supply

This muscle receives blood supply from branches of the occipital, posterior auricular, superior thyroid, and suprascapular arteries.

Function

The function of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is determined by whether it acts alone or with its contralateral counterpart.

When the head contracts unilaterally, the neck flexes laterally on the same side (ipsilateral) and rotates laterally to the other side (contralateral).

Bilateral contraction of the sternocleidomastoid muscles causes neck flexion, which draws the head towards the chest.

During forced inspiration, the thoracic cavity can be expanded by raising the sternum and clavicle using the sternocleidomastoid muscle when the head and neck are fixed.

Splenius capitis muscle

Origin

The splenius capitis comes from the spinous processes of vertebrae C7-T3 and the nuchal ligament.

Insertion

It inserts immediately below the temporal bone’s mastoid process and the occipital bone’s lateral superior nuchal line.

Innervation

innervated by the lower and middle cervical spinal nerves’ posterior rami.

Blood supply

The splenius muscles receive blood from the occipital and transverse cervical arteries.

Function

When the splenius muscles are contracted bilaterally, the head is extended; when they are contracted unilaterally, the head is flexed laterally and rotates to the same side.

Longus Capitis

Origin

The longus capitis is a long, flat muscle that forms four thin muscle strips from the anterior tubercles of vertebrae C3-C6’s transverse processes.

Insertion

Before inserting into the inferior surface of the basilar portion of the occipital bone, these muscle strips pass superiorly and medially.

Innervation

The muscle is innervated by the anterior rami of spinal nerves C1 to C3.

Blood supply

The ascending pharyngeal artery, the ascending cervical branch of the inferior thyroid artery, and the muscular branches of the vertebral artery all provide blood flow.

Function

When acting bilaterally, the longus capitis muscle acts as a weak head flexor, whereas unilateral contraction causes ipsilateral rotation of the head.

Longus colli.

The longus colli, also known as the longus cervicis, is a long muscle that runs the entire length of the cervical spine and upper vertebrae of the thoracic spine. It’s divided into three parts.

- The superior part originates from the anterior tubercles of the transverse processes of vertebrae C3-C5 and connects to the anterior tubercle of vertebra C1.

- The intermediate part originates on the anterior surface of vertebrae C5-T3 and inserts into the anterior surface of vertebrae C2-C4.

- The inferior part protrudes from the anterior surface of vertebral bodies T1-T3 and inserts into the anterior tubercles of transverse processes C5-C6.

Innervation

The muscle is innervated by the anterior rami of spinal nerves C2-6.

Blood supply

It receives blood from branches of the vertebral, inferior thyroid, and ascending pharyngeal arteries.

Function

Neck flexion is the main purpose of the longus colli. Furthermore, the inferior part of the muscle can cause the neck to flex weakly on one side and rotate on the opposite side.

Rectus capitis anterior.

Origin

The anterior surface of the lateral mass of the atlas (C1 vertebra) is the source of the short strap muscle known as rectus capitis.

Insertion

inserts into the basilar part of the occipital bone, before the foramen magnum.

Innervation

This muscle is innervated through the anterior rami of spinal nerves C1 and C2.

Blood supply

It gets blood from the ascending pharyngeal and vertebral artery branches.

Function

The rectus capitis anterior flexes the head and stabilises the atlantooccipital joint.

Rectus Capitis Lateralis

Origin

The superior surface of the transverse process of the atlas (C1) is the source of the rectus capitis lateralis, a small muscle.

Insertion

ascends superiorly to attach to the inferior surface of the jugular process of the occipital bone.

Innervation

Branches of spinal nerves C1 and C2’s anterior rami innervate the muscle.

Blood supply

vascularized by the ascending pharyngeal, vertebral, and occipital arteries.

Function

At the atlanto-occipital joint, the rectus capitis lateralis flexes the head laterally and aids in stabilising it during movement.

Anterior Scalene Muscle

The anterior scalene muscle is located the furthest anteriorly.

Origin

It comes from the transverse processes of vertebrae C3–C6 anterior tubercles.

Insertion

inserts into the superior border of the first rib and the scalene tubercle.

Innervation

The anterior rami of the spinal nerves C4-6 innervate the anterior scalene muscle.

Blood supply

vascularized by the inferior thyroid artery’s ascending cervical branch.

Function

The anterior scalene muscle’s mode of action and whether it cooperates with its contralateral counterpart or acts independently define its function.

When the ribs are fixed and the muscle is acting from below, bilateral contraction of the anterior scalene results in neck flexion. Unilateral contraction of the muscle results in lateral flexion of the neck on the same side.

When the vertebral column is fixed, the muscle elevates the first rib, which, combined with the action of the external intercostals, increases the anteroposterior diameter of the thoracic cage. This action is necessary during forced respiration.

Middle scalene muscle.

Origin

The transverse processes of the axis (C2) and atlas (C1), as well as the posterior tubercles of the transverse processes of vertebrae C3–C7, give rise to the middle scalene, the largest of the scalene muscles.

Insertion

The muscle then moves posterolaterally to attach to the superior border of the first rib.

Innervation

The middle scalene muscle gets its nerve supply from the anterior rami of cervical spinal nerves C3-C8.

Blood supply

It receives blood from the inferior thyroid artery’s ascending cervical branch.

Function

The middle scalene muscle’s primary function is to produce ipsilateral neck flexion when acting from below. When the cervical section of the vertebral column is fixed and the muscle acts from above, it stabilises or raises the first rib during forced inspiration.

Posterior Scalene Muscle

Origin

The posterior scalene is the smallest and most posterior of the scalene muscles, originating from the posterior tubercles of the transverse processes of cervical vertebrae C4-C6. It extends posterolateral.

Insertion

enters the second rib’s external surface.

Innervation

The anterior rami of spinal nerves C6–C8 provide the nerve supply to the posterior scalene muscle.

Blood supply

It receives blood from the ascending cervical branch of the inferior thyroid artery and the transverse cervical branch of the thyrocervical trunk.

Function

The posterior scalene, like the middle scalene, serves primarily to ipsilaterally flex the neck when acting from below and to stabilise or elevate the second rib when acting from above.

Neck muscles pain

Neck pain or stiffness is usually caused by poor posture, overuse, or an awkward sleeping position. However, it can also indicate a serious injury, such as whiplash, or an illness, in which case medical attention may be required.

Your neck is made up of vertebrae that span from the skull to the upper torso. Shock is absorbed between the bones by the cervical discs.

The bones, ligaments, and muscles in your neck support your head and allow for movement. Any abnormalities, inflammation, or injury can result in neck pain or stiffness.

If you have neck pain that lasts more than a week, is severe, or is accompanied by other symptoms, seek medical attention right away.

Symptoms of Neck Muscle Pain:

Neck pain symptoms vary in severity and duration. Neck pain is often acute, lasting only a few days or weeks. Other times, it can become chronic. Your neck pain may be minor and not interfere with your activities or daily life, or it may be severe and cause disability.

The symptoms of neck pain may include:

- Stiff neck. People suffering from neck pain frequently report feeling “stiff” or “stuck.” Neck pain can occasionally cause a reduction in range of motion.

- Sharp pain. Neck pain may feel sharp or “stabbing” and be limited to a specific area.

- Pain while moving. Neck pain is frequently exacerbated by moving, twisting, or extending your cervical spine from side to side or up and down.

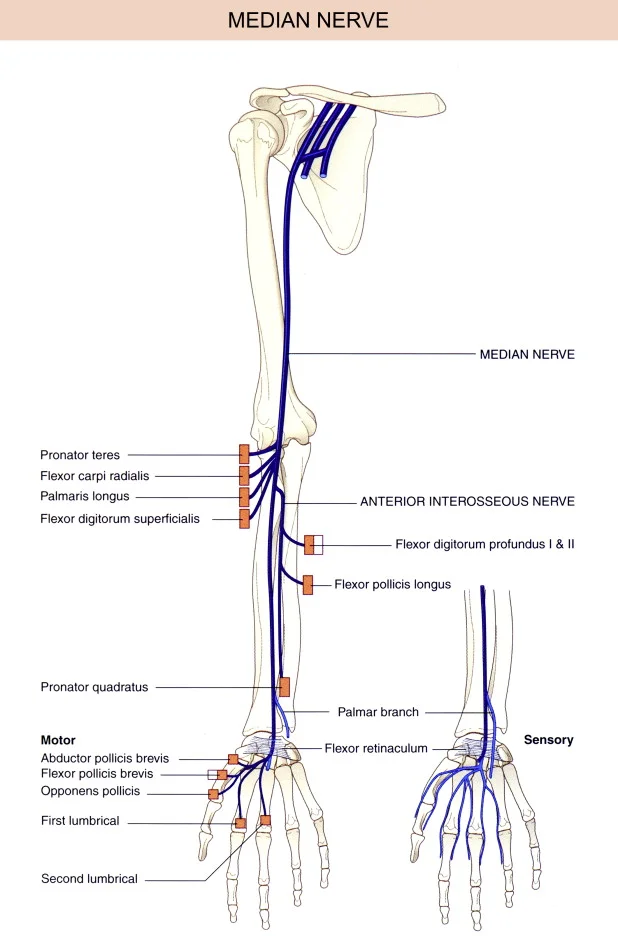

- Radiant pain or numbness. Your neck pain may spread to your head, trunk, shoulders, and arms. If your neck pain is caused by nerve compression, you may experience numbness, tingling, or weakness in one or both arms or hands. A pinched nerve in the neck can cause burning or sharp pain that travels down the arm.

- Headache. Neck pain with a headache could also be a sign of a migraine headache.

- Pain on palpation. Palpating your cervical spine may worsen your neck pain.

Causes

Because the neck bears the weight of the head, it is susceptible to injuries and conditions that cause pain and limit movement. Neck pain can have some causes:

- Muscle strains. Overuse, such as spending too many hours hunched over a computer or smartphone, is a common cause of muscle strain. Even something as simple as reading in bed can put a strain on the neck muscles.

- Joints that have become worn. Neck joints, like other joints in the body, wear with age. In response to this wear and tear, the body frequently develops bone spurs, which can impair joint motion and cause pain.

- Nerve compression. Herniated discs or bone spurs in the cervical vertebrae can press on nerves that branch from the spinal cord.

- Injuries. Whiplash is a common injury caused by rear-end collisions. This happens when the head jerks backward and then forwards, straining the neck’s soft tissues.

- Diseases. Neck pain can be caused by several diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, meningitis, and cancer.

Exercises of neck muscles

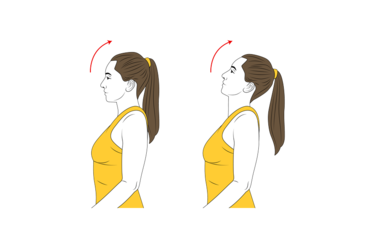

Neck Extension

Without arching your back, slowly move your head backwards, looking upward. Hold for 5 seconds. Return to the starting position. This is a good exercise to do at work to avoid neck strain.

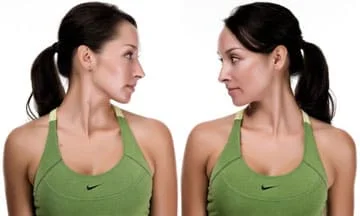

Neck Rotation

Begin by looking straight ahead. Slowly turn your head left. After ten seconds of holding, return to the starting position. Then slowly turn your head to the opposite side. Hold for ten seconds. Return to the starting position. Do ten repetitions. This is a good exercise to do at work, especially if you need to keep your head in a steady position for long periods, such as when working on a computer. To prevent neck strain, perform this exercise every thirty minutes.

Lateral Extension

Begin by looking straight ahead. Slowly lean your head to the left. Use your left hand as resistance and the muscles in your neck to press against it. After five seconds of holding, move back to the initial position. Then slowly lean your head to the opposite side. Hold for five seconds. Return to the starting position. Perform ten repetitions.

This is a good exercise to do at work, especially if you need to keep your head in a steady position for long periods, such as when working on a computer. To prevent neck strain, perform this exercise every thirty minutes.

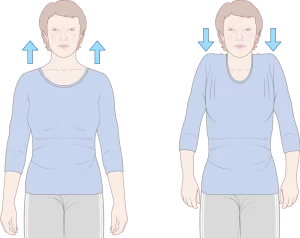

Shoulder shrugs.

Begin by looking straight ahead. Slowly raise both shoulders upward. After five seconds of holding, move back to the initial position. Do ten repetitions. This is a good exercise to do at work, especially if you need to keep your head in a steady position for long periods, such as when working on a computer. To prevent neck strain, perform this exercise every thirty minutes.

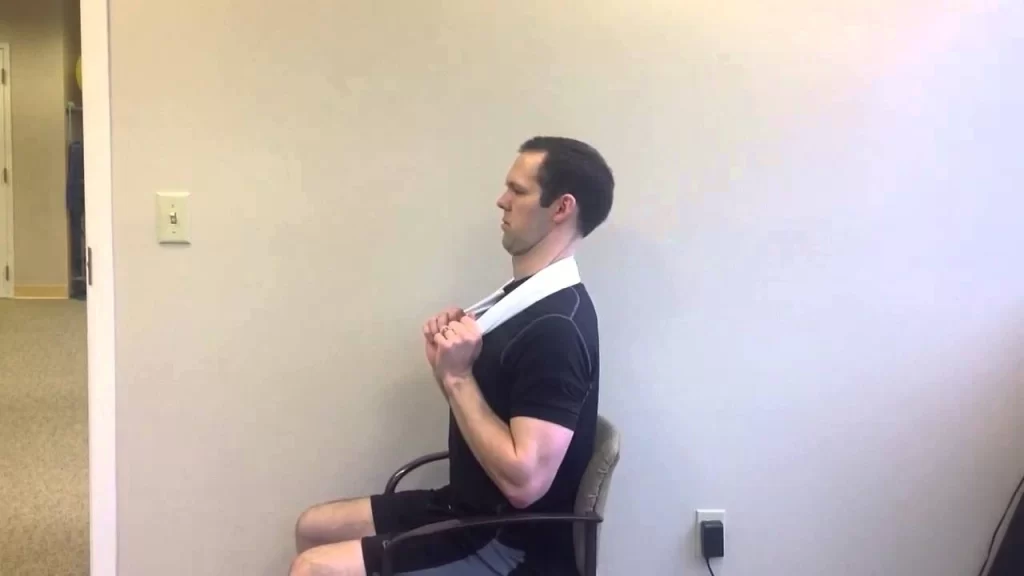

Cervical Retraction

The single most effective exercise for improving posture and neck stability, and it can be done while sitting at your desk. Cervical retraction is best learned while lying down.

Lie on your back, neck relaxed.

Keep your head on the ground and gently tuck your chin towards your chest, creating a double chin. Squeeze and hold for 5 to 10 seconds. Repeat ten times.

Avoid pushing your head into the floor, and make sure you feel a contraction in the front of your neck.

To perform cervical retraction seated, sit upright with your feet flat on the floor.

Gently tuck your chin into your chest while keeping your gaze fixed on something in front. Squeeze and hold for 5 to 10 seconds.

Isometric Cervical Side Bending

Stand or sit upright, head in a neutral position, feet flat on the floor.

Put your hand on your head’s side.

Keep your eyes fixed on something in front of you and gently push into the side of your head, resisting the motion with your neck muscles.

Make sure your head remains steady.

Scapular Retraction.

Begin by sitting or standing with your back against a wall in an upright position.

Squeeze the shoulder blades together and downward. Hold for 5–10 seconds. Repeat ten times for one or two sets.

Maintain a tucked chin, and arms by the sides of the body, and avoid shrugging shoulders.

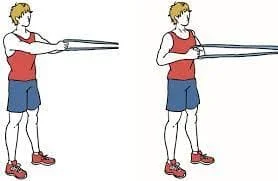

Theraband Row

Stand with arms in front of your chest, holding the ends of a resistance band anchored at chest height.

Bend elbows and pull arms back against resistance, as if squeezing shoulder blades together.

Maintain a straight posture and avoid shrugging your shoulders.

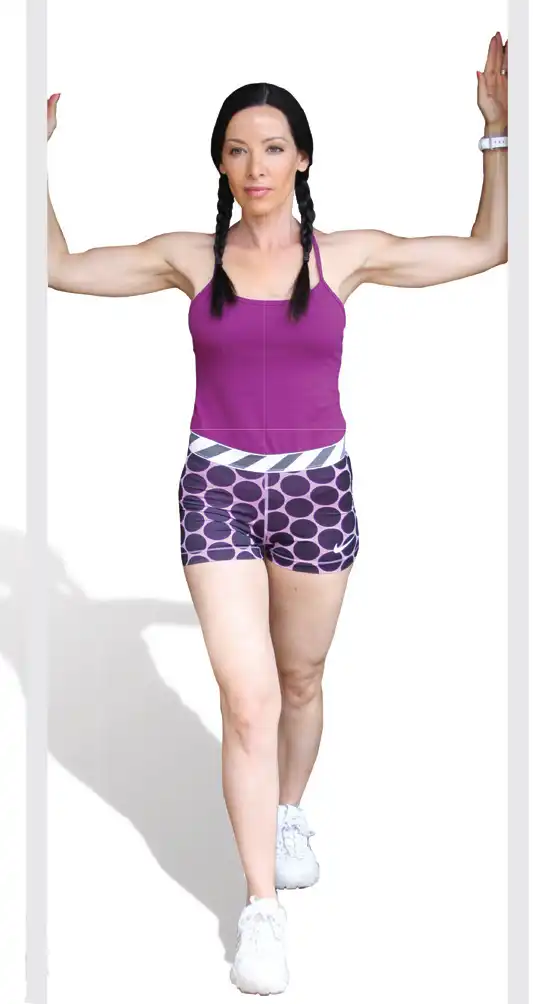

Doorway Shoulder Stretch

Stand straight in the front and centre of a doorway.

Place your palms and forearms on the sides of the doorway at a comfortable height.

Take a small step forward and push your pelvis forward until you feel a stretch in the front of your shoulders. Hold for 30-40 seconds.

Summary

Neck muscles are tissues that cause motion in the neck and extend from the base of the skull to the upper back. They work together to bend the head and aid in breathing. There are several types of neck muscles, including Platysma, Sternocleidomastoid, Splenius capitis, Longus capitis, Longus colli, Rectus capitis anterior, Rectus capitis lateralis, Scalanus anterior, Scalanus medius, and Scalanus posterior.

Neck pain or stiffness is usually caused by poor posture, overuse, or an awkward sleeping position. It can indicate a serious injury or illness, and symptoms may include stiff neck, sharp pain, pain while moving, radius pain or numbness, headache, and pain on palpation. Causes include muscle strains, worn neck joints, nerve compression, injuries, and diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, meningitis, and cancer.

Exercises for neck muscles include neck extension, neck rotation, shoulder shrugs, cervical retraction, isometric cervical side bending, scapular retraction, theraband row, doorway shoulder stretch, and hamstring stretch. To prevent neck strain, engage in exercises such as cervical retraction every 30 minutes. Seek medical attention if neck pain lasts more than a week, is severe, or is accompanied by other symptoms.

FAQs

What’s the most common neck issue?

The most common neck injuries are Neck sprain or strain – A sprain occurs when the neck’s ligaments tear. A strain is a torn muscle or tendon. This can happen as a result of a sudden injury from physical activity or even a minor car accident.

What is your neck’s main muscle called?

Sternocleidomastia (SCM).

The head can be tilted upward or rotated to one side depending on whether one or both of the SCM muscles (one on each side of the neck) are contracted. It is a large muscle that protects some delicate structures, including the carotid artery.

What’s the term for pain in the nerves?

Nerve pain, also known as neuralgia or neuropathic pain, occurs when a health condition impairs the nerves that transmit sensations to the brain. Nerve pain may feel different from other types of pain.

What are the top 5 causes of neck pain?

Some common causes of neck pain include:

Poor posture (your body’s position when standing or sitting)

Sleeping in an awkward position.

Tension in your muscles.

Injuries such as muscle strains or whiplash.

Extended use of a desktop or laptop computer.

A herniated or slipped spinal disc

What controls the neck muscles?

Efferent nerves carry impulses from the spinal cord, which cause muscles to contract and control cervical movements. Cervical nerves C2-C4 send sensations to the anterior neck, while cervical roots C4-C5 send sensations to the posterior neck.

References:

- Neck pain – Symptoms and causes – Mayo Clinic. (2022b, August 25). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/neck-pain/symptoms-causes/syc-20375581#:~:text=Neck%20pain%20is%20common.,of%20a%20more%20serious%20problem.

- Pietrangelo, A. (2023, April 20). Neck Pain: Symptoms, Causes, and How to Treat It. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/neck-pain

- Muscles of the neck: An overview. (2023, October 30). Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/muscles-of-the-neck-an-overview

- Taylor, M. (2022, October 7). Neck Muscles: What to Know. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/neck-muscles-what-to-know

- Physiotherapist, N. P. (2023, December 13). Neck Muscles: Origin, Insertion, Innervation, Exercise. Mobile Physiotherapy Clinic. https://mobilephysiotherapyclinic.in/neck-muscles-detail-and-exercise/#google_vignette

- Athletico. (2022, August 10). 9 Exercises to Strengthen Your Neck & Shoulders – Athletico. Athletico. https://www.athletico.com/2020/10/16/9-exercises-to-strengthen-your-neck-shoulders/

- 9 Stretches to Relieve Neck Pain | Fort Worth Bone & Joint Clinic. (n.d.). https://thcboneandjoint.com/educational-resources/neck-exercises.html

19 Comments