Diaphragm Muscle

What Is The Diaphragm Muscle?

The diaphragm, an essential respiratory muscle, divides the thoracic and abdominal areas. It is positioned below the lungs and is critical for breathing because it contracts and relaxes to change the volume of the thoracic cavity. The diaphragm contracts during inhalation, removing and expanding the thoracic cavity to facilitate the rapid entry of air into the lungs.

The diaphragm relaxes and takes on a dome-like form during exhalation, which lowers the thoracic volume and improves air outflow. This involuntary muscle is essential to respiratory function since it is always working to maintain life.

It is an important part of deep breathing exercises, increasing the body’s oxygen content and offering many other health benefits. Incorporate this workout into your daily training routine to improve your overall health.

The diaphragm is a single, dome skeletal muscle located inside the trunk. It is the primary muscle that is engaged in inspiration the diaphragm, or breathing, muscle contracts to allow the thoracic cavity to extend.

Consequently, inspiration and lung expansion improves when the cavity’s capacity rises and the intrathoracic pressure decreases. There is more to the diaphragm than only the membrane separating your abdominal and thoracic regions.

Structure Of Diaphragm Muscle

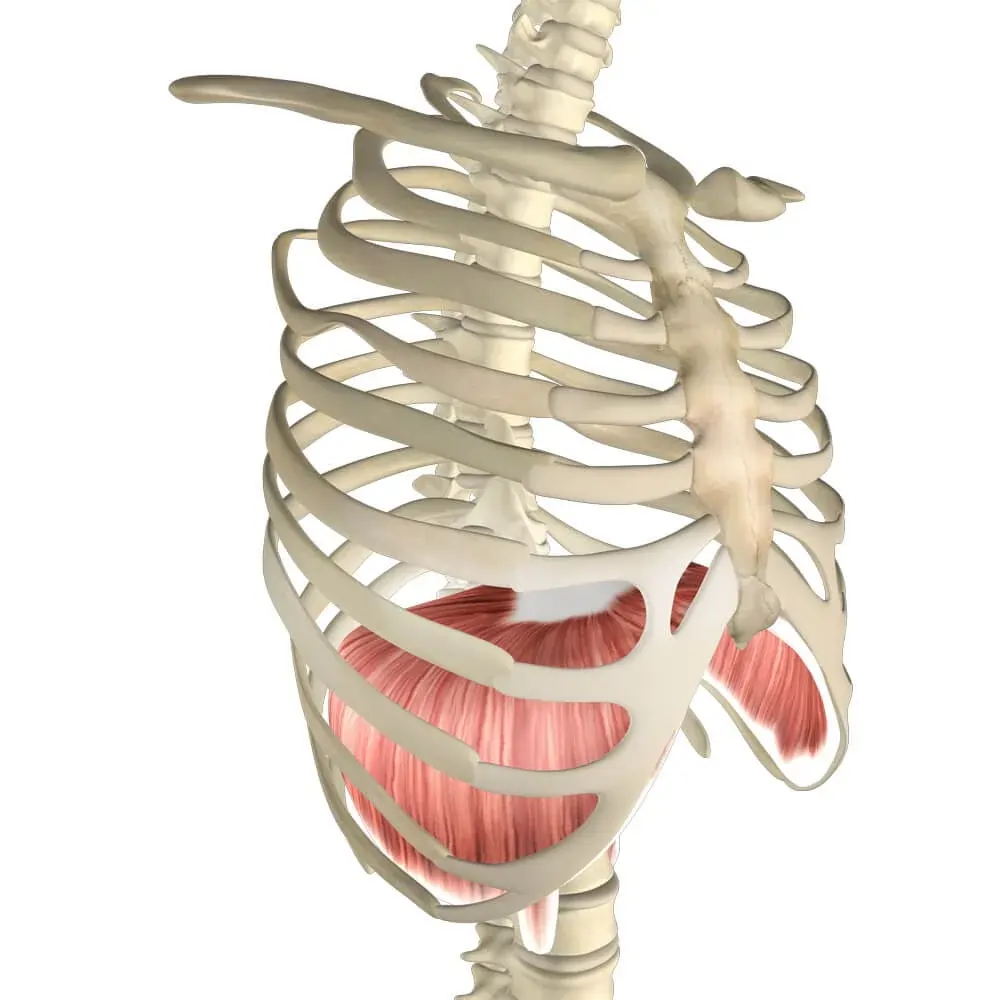

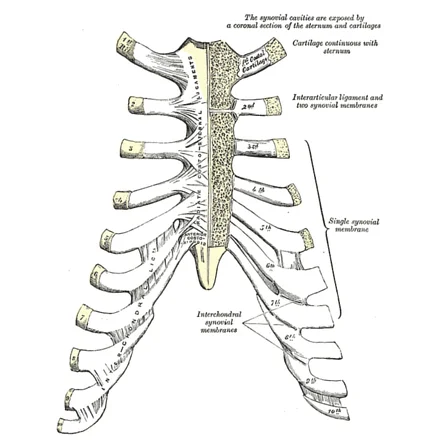

The diaphragm is a covering of muscle and tendon. Its three muscular segments the lumbar, costal, and sternal each have their origin and are inserted into the diaphragm’s central tendon. The diaphragm is shaped like two structures with the liver causing the right dome to be positioned somewhat higher than the left. The diaphragm is partially lowered by the pericardium, which is the cause of the depression between the two structures.

The thoracic and abdominal surfaces make up the diaphragm. The pericardium and pleura, two serious membranes found in the heart and lungs, are in contact with the thoracic diaphragm.

Function Of Diaphragm Muscle

One of the primary breathing muscles is the diaphragm. The diaphragm flattens when the muscular fibers tighten. Air enters the lungs and the thoracic cavity’s capacity grows vertically, lowering intrapulmonary pressure. Air from the lungs, intrapulmonary pressure rises, and thoracic volume decreases when the diaphragm relaxes.

Origin Of Diaphragm Muscle

The sternal part of the diaphragm originates at the posterior aspect of the xiphoid process.

The inside surfaces of the ribs and lower costal cartilage are the origin of the coastal portion of the diaphragm.

The bodies of vertebrae L1 through L3 and the anterior longitudinal ligament are the origin of the lumbar portion of the diaphragm.

Insertion Of Diaphragm Muscle

The central tendon absorbs the diaphragm.

Nerve Supply

The phrenic nerves (C3–C5) supply the diaphragm with motor innervation. After penetrating the diaphragm, these neurons innervate it from its abdominal surface. The phrenic nerves innervate the pain and proprioception at the core tendinous section, and the sixth to eleventh intercostal nerves innervate the peripheral muscular portions.

Blood supply

The respiratory diaphragm receives blood from multiple arteries since it is a vast, complicated muscle. The subcostal arteries and the five most inferior pairs of intercostal arteries supply blood to the coastal region of the diaphragm.

The diaphragm is supplied by a few branches of the inferior phrenic arteries, which are closely connected to it. They provide the diaphragm’s primary vascular supply. The inferior surface of the diaphragm is connected to the left diaphragmatic crus, which is reached by the left inferior phrenic artery. From this point on, it continues along the edge of the gastric hiatus anteriorly and passes posterior to the esophagus. The right travels anteriorly along the vena cava hiatus and behind the IVC.

Every artery produces medial branches that anastomose with the pericardiophrenic, musculophrenic, and inferior posterior intercostal arteries, as well as lateral branches that anastomose with the musculophrenic and inferior posterior intercostal arteries near the thoracic wall.

Action

Depression of the main inspiration muscle, the costal cartilage.

Clinical Significance

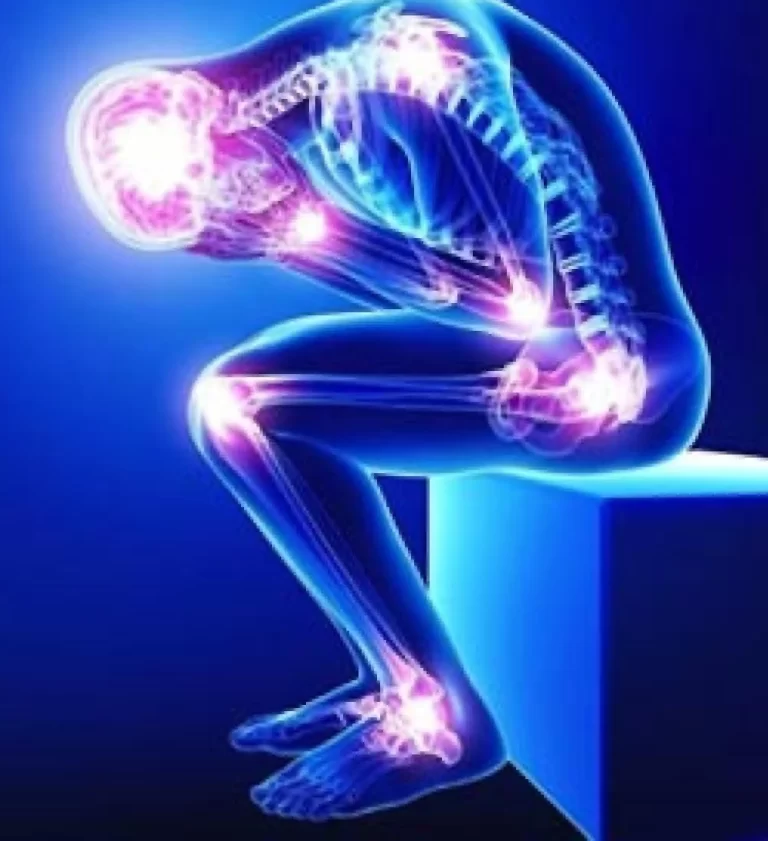

Paralysis of the Diaphragm

One cause of diaphragmatic paralysis is an issue in the nerve supply. The brainstem, cervical spinal cord, or phrenic nerve may all experience this. Most often, damage to the phrenic nerve causes it.

Mechanical trauma: a nerve injury or blockage caused during surgery.

Compression: a tumor’s cause

Myopathies: myasthenia gravis is one example.

Diabetic neuropathy is one type of neuropathy.

A paradoxical movement is produced when the diaphragm muscle is paralyzed. During inspiration, the diaphragm muscle on the affected side travels upward, and during expiration, it descends downward. The diaphragm’s unilateral paralysis is typically affected and discovered by accident on an x-ray. The patient may have the condition and fatigue if both sides are paralyzed.

Diaphragmatic hernia

When one or more abdominal organs protrude through the diaphragm’s hole and into the chest, this condition is known as a diaphragmatic hernia. It can occasionally exist from birth. This condition is known as a congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH).

A diaphragmatic hernia can also result from surgery or accident-related injuries. It’s known as an acquired diaphragmatic hernia (ADH) in this instance.

Depending on the organs affected, the size of the hernia, and the reason, symptoms can change. They could consist of:

- difficulty breathing

- rapid breathing

- rapid heart rate

- blueish-colored skin

- bowel sounds in the chest

To remove the abdominal organs from the chest cavity and repair the diaphragm, both an ADH and a CDH require emergency surgery.

Cramps and spasms

It is possible to confuse chest discomfort and dyspnea caused by a diaphragmatic cramp or spasm for a heart attack. Sweating and nervousness are also common side effects of diaphragm spasms in certain persons. Some people say that during a spasm, they feel as though they are unable to breathe fully.

The diaphragm does not contract again after exhaling during a spasm. This causes the diaphragm to tighten as the lungs expand. Additionally, this may result in chest cramps. Exercise that is too vigorous might cause the diaphragm to spasm, which frequently causes a side stitch.

Phrenic nerve damage

Cancer, inflammatory disorders, and trauma can all cause damage to the nerves. Additionally, it could occur during procedures like lung transplants and cardiac bypass surgery. Compression or injury to the Phrenic nerve might result from a tumor, an aortic rupture, or cervical spondylosis. Inflammation of the nerve can result from diseases like Lyme disease and conditions like HIV.

- traumatic injuries

- surgery

- cancer in the lungs or nearby lymph nodes

- spinal cord conditions

- autoimmune disease

- neuromuscular disorders, such as multiple sclerosis

- certain viral illnesses

This injury may result in diaphragm dysfunction or paralysis. However, phrenic nerve injury is not always accompanied by symptoms. When it does, the following signs could appear:

- shortness of breath when lying flat or exercising

- morning headaches

- trouble sleeping

Diaphragmatic flutter

Diaphragmatic flutter is an uncommon ailment that is frequently misdiagnosed as a spasm. A person may experience the fluttering as a pulsating sensation in the abdomen wall during an episode.

It may also result in:

- shortness of breath

- chest tightness

- chest pain

- abdominal pain

Symptoms of a diaphragm

The symptoms of a diaphragm disorder can resemble those of a heart attack. If you feel pressure or pain in your chest that radiates to your jaw, neck, arms, or back, get emergency medical attention.

Among the signs of a diaphragm problem are:

- difficulty breathing when lying down

- shortness of breath

- chest, shoulder, back, or abdominal pain

- pain in your lower ribs

- a fluttering or pulsing sensation in the abdomen

- bluish-colored skin

- heartburn

- trouble swallowing

- regurgitation of food

- upper abdominal pain after eating

- hiccups

- side pain

Tips for a healthy diaphragm

Because it is so vital to breathing, the diaphragm is one of the most significant muscles in the body.

Safeguard your diagram by:

- limiting foods that trigger heartburn or acid reflux

- eating smaller portions of food at a time

- stretching and warming up before exercise

- exercising within your limits

With targeted exercises, you can build your diaphragm just like any other muscle. The best way to do this is with abdominal or diaphragmatic breathing. It entails taking slow, deep breaths through the nose to fill your lungs with air as your belly grows. Diaphragmatic breathing not only strengthens your diaphragm but also lowers blood pressure and relieves stress.

Treatment of Diaphragm Muscle

Diaphragmatic paralysis therapy is mostly influenced by the patient’s symptoms and the underlying causes of their disease. Most of the time, patients with asymptomatic unilateral involvement don’t require medical attention. First, it is important to treat any contributing factors that may alter and increase paralysis symptoms, including obesity, respiratory disorders, and chronic cardiac problems.

Certain treatments are accessible when the reason of paralysis is known and potentially curable, such as in cases of viral infections, metabolic diseases, endocrinological abnormalities (such as diabetes or hypothyroidism), or systemic erythematosus lupus (shrinking lung syndrome). It’s important to remember that paralyzed idiopathic reasons, like amyotrophic neuralgia, may resolve on their own. Other studies have shown that 40–60% of individuals with diaphragmatic paralysis that may have a reversible origin (surgical, paraneoplastic, diabetic neuropathy, etc.) may experience spontaneous resolution over time, indicating the convenience of postponing any surgical therapy.

Under supervision, the patient could take part in a specialized respiratory rehabilitation program. Research has shown that a year of inspiratory muscle training after heart surgery improves both inspiratory muscle strength and diaphragmatic mobility in those with diaphragmatic dysfunction.

Surgical diaphragmatic Plication

This is the main surgical treatment used to treat dyspnea in patients with diaphragmatic paralysis. To immobilize in the maximal inspiration position and relieve pressure on the lung parenchyma, the paralyzed diaphragm is folded, allowing for lung reexpansion. There are two possible approaches: abdominal or thoracic (with thoracoscopy).

It is mostly advised for symptomatic patients with unilateral diaphragmatic dysfunction that has persisted and is thought to be irreversible after six to twelve months of monitoring based on clinical, radiological, and functional testing results. Furthermore, successful plication has been performed on a few patients with bilateral involvement. In the surgically treated group, trauma, heart surgery, and iatrogenic reasons were the three main causes of paralysis.

It has been shown that plication is effective, safe, and causes a few side effects in addition to alleviating symptoms and dyspnea. In addition to radiological exams, improved pulmonary function measures can demonstrate the benefits of plication. The tidal volume of the hemidiaphragm (both the healthy and the operated), exercise capacity, daily activity, and quality of life all improve after surgery, with a reduction in score on the Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire of up to 20 points.

These improvements are likely due to a significant improvement in the expansion of the abdominal compartments of the rib cage. Many people can return to their normal life as a result of all of this. Morbid obesity, diaphragm calcification, and some neuromuscular diseases are considered relative contraindications.

Microsurgical restoration of the phrenic nerve

This surgical approach, which includes procedures like local decompression, transposition, or interposition of a nerve graft, may be helpful for patients with unilateral phrenic involvement that is primarily iatrogenic or traumatic in origin and who have not shown any clinical or radiological improvement in a reasonable amount of time. It is necessary to first demonstrate the neuromuscular plate’s vitality and the nerve’s continuity using PN conduction studies and electromyography.

Pacemaker with a diaphragm

Patients with decreased bilateral diaphragmatic mobility who choose to postpone initiating invasive or non-invasive ventilation, or who have started ventilation but are unwilling to continue, may find it too difficult to manage. In addition to cervical involvement, these patients frequently have other central abnormalities, mainly congenital or acquired central hypoventilation, or cervical involvement at a level higher than C3. It can also be seen in people with lower motor neuron involvement from illnesses other than amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, traumatological disorders, or isolated reasons.

The most relevant study on the use of a diaphragmatic pacemaker in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis that has been published so far has not proven its expected benefits due to increasing death rates in pacemaker patients. Therefore, at this time, it is not advised for this type of patient. Patients undergoing this treatment must be carefully selected and assessed at recognized facilities; it is necessary to confirm severe hypoventilation during the night and to show excellent lung, diaphragm, and PN function.

Ventilation assistance

It has been effectively used by patients with both unilateral and bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis, either long-term in the latter instance or short-term in the former until complete diaphragmatic function was regained. Ventilation support can be obtained through intrusive mechanical ventilation or positive pressure ventilation (NPPV).

In general, NPPV is an effective treatment for symptomatic persons with bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis. It has been shown that tolerance can lead to long-term improvements in blood gas and clinical indicators. Non-invasive breathing would provide similar signals for other neuromuscular or restrictive illnesses.

Patients with acute respiratory failure may require prolonged mechanical ventilation and intubation due to respiratory muscle paralysis. A study of 152 patients with spinal cord injury, 50% of whom had affectation at the C3-C5 level, found that early tracheostomy reduces the duration of invasive ventilation, the length of stay in the intensive care unit, and the incidence of complications related to orotracheal intubation, except ventilation-associated pneumonia.

On the other hand, in cooperative patients with bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis, a restricted volume of secretions, and a reasonable inspiratory flow, non-invasive ventilation has been recommended as a weaning approach before tracheostomy.

Neuromuscular disease patients may also require invasive ventilation and a tracheostomy if non-invasive ventilation has failed or if invasive therapy are not successful.

There are several challenges associated with non-invasive ventilation. The use of masks may result in small-scale, transient issues. Strict patient selection and breathing management can lower the possibility of serious side effects from:

(1)Ventilation failure;

(2) Ventilation-associated pneumonia;

(3) Barotraumas; and

(4) Hypotension.

Patients on invasive ventilation are less likely to encounter these issues than patients not receiving it.

Exercises Of Diaphragm Muscle

Stretching Exercise Of Diaphragm Muscle

Intercostal Stretching Breath

- To execute the diaphragm stretch, the patient must lie supine with their hips and knees bent 90 degrees.

- The patient’s proximal thighs should be touched with their heels.

- The patient has to take a few calm breaths through their nose.

- Pushing their hands into their thighs, the patient should exhale deeply and fully.

- The patient should now consider breathing in but not breathing any air.

- Next, instruct the patient to stretch their ribcage and suck in their stomach to create a vacuum.

- Next, the patient should softly extend and flex their spine and pelvis.

- Additionally, lateral shifts will lengthen the diaphragm muscle in several places.

- Repeat three to four times after completing one or two cycles of stable breathing.

Diaphragm Stretches

- The patient stands to perform an intercostal stretching breath.

- Request that your patient extend both arms above their head.

- They should inhale deeply and extend both arms to the right as they exhale.

- Your left side’s intercostal muscles will be stretched as a result.

- They should return to the beginning position when they inhale.

- On the next breath, they should extend their arms to the left to stretch the right intercostal muscles.

- On each side, repeat three times.

Strengthening Exercise Of Diaphragm Muscle

Diaphragmatic breathing exercises

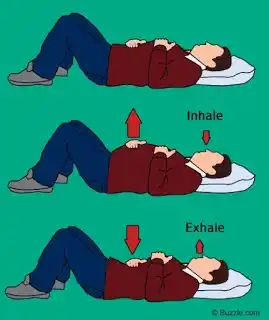

- Lying upon your back on the bed or a level surface, bend your knees and support your head.

- To support both of your legs, place a pillow below each knee.

- Place one hand slightly below your ribcage and the other on your upper chest.

- This will enable you to sense the movement of your diaphragm during breathing.

- gradually The hand rises when you inhale through your nose and your stomach lowers..

- As much as possible, the hand should stay on the upper chest.

- As you release the breath through pursed lips, contract the muscles in your stomach to cause your stomach to shift inside and your hand to drop.

Sandbag Breathing

- The patient is lying in the supine posture.

- They ought to have a straight back.

- Your patient is given a sandbag to lie on their stomach.

- Use the procedures outlined to assist your patient in establishing a comfortable breathing pattern.

- Repeatedly feel the breath coming in and going out.

- Feel the abdomen expand with inhaled breaths and contract with exhaled ones by softening it.

- Breathe naturally, without pausing in between breaths.

Blow Up a Balloon

- In addition to being a fantastic party décor, balloons are a great way to improve your abdominal and diaphragm muscles. Your attempt to release the balloon forces you to inhale too forcefully.

- Lying on the back of the floor with your knees bent, place your feet on the bench, couch, or chair. Hold the balloon in one hand while resting your other arm on the ground behind you. To lift your butt two inches off the floor, press your heels into the bench, couch, or chair.

- Breathe deeply through your nose into the balloon, then exhale through your mouth. When you are at a loss for words, stop. Take a five-second break before inhaling.

- Place your tongue against the roof of your mouth and inhale through your nose. Take in as much air as you can, and finally, forcefully release it into the balloon until your lungs are depleted and then come to a stop.

- This cycle should be continued until the balloon is full. Next, deflate the balloon and give it another go. Blow five times with the balloon.

- Try to unwind your neck and shoulders as you exhale. Your abdomens will be under the most strain as a result.

All-Fours Breathing

- The all-fours breathing exercise is a simple enough activity for a youngster to perform correctly and also encourages diaphragmatic breathing:

- On the ground, assume an all-fours stance. Bend your back gently, as if you were in yoga’s “cat” stance. Ensure that your hips are over your knees and your shoulders are over your hands.

- Breathing in via your nose and out through your mouth is required. Tuck your chin into your chest and curve your back as you exhale. Continue to circle while expelling all of the air from your lungs. Hold the rounded position for five seconds while you pause at the end of your breath. After that, inhale through your nose.

- Breathe out as strongly as possible after your lungs are full, rounding your back even further. After five cycles like this, stop and rest.

Conclusion

The diaphragm is a vital muscle responsible for the mechanics of breathing. It contracts and moves downward during inhalation, allowing the lungs to expand and fill with air, and relaxes during exhalation.

Innervated by the phrenic nerve, it also aids in other functions like aiding venous return to the heart and maintaining intra-abdominal pressure. Dysfunction of the diaphragm can lead to breathing difficulties and other complications, highlighting its crucial role in overall health and well-being.

FAQ

What are the three parts of the diaphragm muscle?

Sternal portion: the xiphoid process’s rear aspect.

The interior surfaces of ribs 7 through 12 make up the costal portion.

Medial and lateral arcuate ligaments in the lumbar region.

Can you strengthen the diaphragm muscle?

The muscle responsible for eighty percent of your breathing is the diaphragm. The primary function of the diaphragm muscle is to support respiration, which can assist your body in adjusting to increases in intensity during exercise. You may train your diaphragm muscle and improve your total aerobic performance the same way you would with any other muscle.

Does yoga strengthen the diaphragm?

Breathing is assisted by the diaphragm, a muscle located at the base of the lungs. Weakness in the diaphragm muscle can contribute to respiratory issues and breathing difficulties. For this reason, it’s critical to perform yoga positions that support and strengthen the diaphragm.

What makes your diaphragm weak?

Physical trauma to the diaphragm muscle or phrenic nerves is the most common cause of weakening of the diaphragm brought on by medical intervention. Examples that have been identified include head and neck surgery, central venous catheterization, and neuropraxia brought on by using ice slush during cardiothoracic surgery.

What does a weak diaphragm feel like?

Breathlessness while walking, resting flat, or covered in water up to the lower chest are signs of severe, typically bilateral paralysis or weakness of the diaphragm muscles. Reduced blood oxygen levels and sleep-disordered breathing can result from bilateral paralysis of the diaphragm muscles.

How can I improve my diaphragm breathing?

You must take your place in the chair, bending at the knees and maintaining a relaxed head, neck, and shoulders. Put your left hand directly behind your rib cage and your right hand on your upper chest. This will enable you to sense the diaphragm’s movement during inhalation. Breathe slowly through your nose, pushing your tummy into your hand as you inhale. A still as possible may be maintained with the hand on the chest. As you exhale through pursed lips, contract your abdominal muscles to force your stomach back in. The hand on top of the chest needs to stay there.

What is the blood supply of the diaphragm?

The pericardiacophrenic, inferior phrenic, musculophrenic, superior phrenic, and lower internal intercostal arteries provide blood to the diaphragm. The thoracic aorta is the origin of the superior phrenic arteries.

Where is the diaphragm located?

One muscle that assists with breathing in and out is the diaphragm. This slender, dome-shaped muscle is located beneath your heart and lungs. It is joined to your spine, the bottom of your rib cage, and the sternum, a bone in the middle of your chest.

Is a paralyzed diaphragm serious?

Bilateral diaphragm paralysis can lead to decreased blood oxygen levels and breathing disorders during sleep. Due to weaker muscles and a more supple chest wall, newborns and children with unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis may have more severe respiratory discomfort than adults.

What is the action of the diaphragm muscle?

The main breathing muscle is the diaphragm. It flattens and tightens during inspiration motion, expanding the thoracic cavity’s vertical diameter. Lung expansion results from this, drawing in air. The diaphragm passively relaxes and assumes its original dome form during expiration action.

2 Comments