Trigger Finger

Overview

Trigger finger is a condition where a finger becomes stuck in a bent position, and may suddenly straighten with a snapping motion. The ring finger and thumb are commonly affected, although any finger can be involved.

This issue arises when the tendon controlling the finger cannot smoothly move within its sheath. Swelling in the sheath or the formation of a small lump on the tendon can lead to this problem.

Trigger finger predominantly affects women over the age of 50, with higher risks seen in individuals with diabetes, low thyroid function, or rheumatoid arthritis.

Treatment options for trigger fingers include splinting, steroid injections, or surgery.

What is a Trigger finger?

Since both fingers and thumbs have tendons that are capable of being reliably flexed, trigger fingers are a common and treatable condition. These tendons are surrounded by a lining called tenosynovium and covered by soft tissue known as pulleys, allowing them to move smoothly.

Trigger finger, also known as trigger thumb or stenosing tenosynovitis, can develop if the tendon enlarges, the lining thickens, or the pulley increases in size. Any change in the correct size of these structures can lead to problems as the tendon gets stuck within the pulley, causing thickening of the lining and increased fluid production, resulting in pressure buildup. This can also lead to the pulley thickening and causing friction, making it challenging for the tendon to move.

Diagnosing the trigger finger typically involves a history, symptoms, and physical examination, with additional tests rarely needed. Fortunately, several effective treatments are available for this condition.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

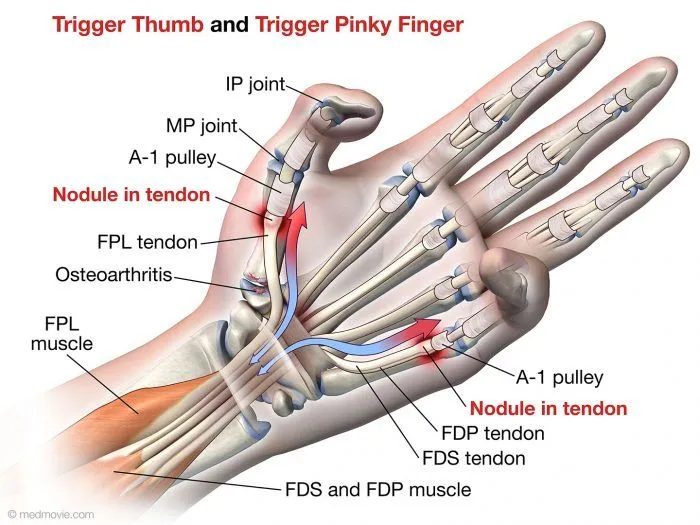

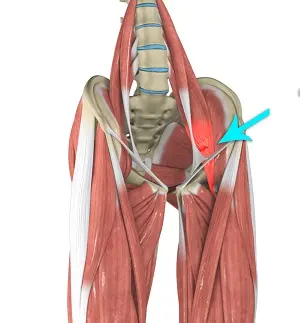

Flexor Tendons: The flexor tendons that bend the fingers run through fibrous tunnels called tendon sheaths in the palm and fingers. The affected tendon in the trigger finger is the flexor tendon of the affected finger.

Tendon Sheath: The flexor tendons pass through a series of fibrous tunnels called tendon sheaths that are formed by thickenings of the tendon lining (tenosynovium). At the base of the fingers, the tendon sheaths form a ring through which the tendons must glide, called the annular pulley.

Annular Pulley: The annular (A1) pulley is a thick, rigid fibrocartilaginous ring at the base of each finger that forms a tunnel for the flexor tendons to enter the finger. This is the area that often becomes inflamed and constricted in the trigger finger.

Flexor Tendon Nodule: With the trigger finger, a small inflamed nodule or swelling can form on the flexor tendon where it passes through the narrowed annular pulley sheath. This causes catching, popping, or locking of the tendon.

Flexor Tendon Sheath: The flexor tendon sheath is the synovial lining that surrounds the flexor tendon as it passes through the tunnel. This sheath can become inflamed and thickened, narrowing the space for the tendon.

Volar Plate: The volar plate is a thick flat ligament between the annular pulleys and the palmar skin. Inflammation here can also contribute to the trigger finger.

Epidemiology/Aetiology

From a statistical perspective, the trigger finger tends to arise more frequently during the fifth or sixth decade of life, with women being up to six times more susceptible to developing it compared to men. On average, the typical age of onset is around 58 years. While the general likelihood of experiencing a trigger finger is around 2-3%, among those with diabetes, this risk increases to 10%. Interestingly, this higher risk in diabetic individuals is not attributed to blood sugar control but rather to the duration of the condition. Additionally, the trigger finger can coincide with conditions such as Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, DeQuervain’s disease, Hypothyroidism, Rheumatoid arthritis, Renal disease, and Amyloidosis.

Various factors have been proposed as potential triggers for the development of trigger fingers in the literature, although there is limited concrete evidence regarding the precise cause. While occupational-related factors have been suggested as contributors to trigger fingers, the correlation between the two remains inconsistent based on current research. Authors propose that the trigger finger may arise from any activity that necessitates prolonged, forceful flexion of the fingers, such as carrying heavy shopping bags or a briefcase, extended periods of writing, rock climbing, or gripping small tools or objects with sharp edges.

It is crucial to recognize that the development of a trigger finger often results from a combination of factors. The condition may manifest in an idiopathic manner or as a secondary consequence of other underlying pathologies.

Pathophysiology

Microtrauma, whether from repetitive activities or pressure, leads to inflammation and damage to the complex surrounding the flexor tendon. The A1 pulley experiences the highest amount of force and consequently is the most commonly impacted. Over time, the inflammation causes the tendon to become stuck in its sheath, resulting in a sensation of locking for the patient.

Despite the superior strength of the flexor tendon system compared to the extensor tendons, patients typically do not face issues with finger flexion. However, due to the inflammation, the flexor tendon may get caught in the sheath during extension, leading to the sensation of locking when attempting to extend the fingers.

Symptoms of Trigger Finger

- You may experience a painful sensation of clicking or snapping when bending or straightening your finger, especially after periods of inactivity, improving with movement.

- Stiffness in the finger, particularly noticeable in the morning.

- The presence of soreness or a small lump at the finger or thumb’s base is known as a nodule.

- Hearing a popping or clicking sound while moving the finger.

- Encountering a locked finger that cannot be straightened.

These symptoms typically start mildly and worsen gradually, often appearing more prominently after intense hand use rather than due to an injury. They tend to be more pronounced in the morning when gripping something tightly, or when attempting to extend the finger.

Causes of Trigger Finger

Frequent repetitive movements or forceful utilization of the finger or thumb can result in tendon inflammation, leading to a trigger finger.

Trigger finger can also be caused by contact friction, which occurs from gripping something that vibrates. Common sources of contact friction include using power tools or holding onto bicycle handlebars.

Understanding the trigger finger requires knowledge of hand anatomy. Tendons are tough cords that link muscles to bones. The tendon pulls on the bone to cause it to move when a muscle contracts. While tendons are strong, they lack elasticity and are prone to injury from excessive strain, requiring extended healing periods.

Surrounding tendons is a tissue layer called the synovial sheath that enables smooth tendon movement. Soft tissue structures known as pulleys encompass the tendon and the sheath. Normally, the tendon and sheath glide easily through the pulleys.

However, inflammation and swelling of the tendon or sheath can occur. Prolonged irritation can lead to scarring and thickening, affecting the tendon’s movement. This can cause the inflamed tendon to snap or pop when bending the finger or thumb through a narrow sheath.

Common Risk Factors Associated with Trigger Finger

Several factors increase the likelihood of developing a trigger finger, including:

- Age: Typically manifests between 40 and 60 years old.

- Gender: More prevalent in women compared to men.

- Health conditions: Conditions like diabetes, gout, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, thyroid issues, and tuberculosis can contribute to the trigger finger.

- Occupation: Common among farmers, industrial workers, musicians, and individuals who frequently perform repetitive finger and thumb movements.

- Hobbies: Engaging in racket sports such as tennis or pickleball can increase the risk.

- History of carpal tunnel surgery: Most common within the initial 6 months post-operation.

Engaging in work or hobbies that involve repetitive, forceful movements such as grasping, gripping, or applying pressure with your fingers and thumbs can increase the likelihood of developing a trigger finger. Some examples include:

- Agricultural or gardening activities.

- Working in industrial settings or using tools.

- Playing a musical instrument.

- Participating in racket sports like tennis, racquetball, or pickleball.

Individuals with certain health conditions are at a higher risk of developing trigger fingers, including:

- Osteoarthritis.

- Rheumatoid arthritis.

- Gout.

- Diabetes.

- Amyloidosis.

- Thyroid disease.

Diagnosis

History:

- The patient complains of locking, catching, or popping sensation in the affected finger when flexing or extending

- May have difficulty straightening the finger after it has been bent into a flexed position

- Usually, in the morning, symptoms worsen

- May have swelling or pain over the base of the affected finger on the palm side

- Frequently, symptoms begin gradually and get worse over time.

- Asks about any prior injury or overuse of the hand/finger

Physical Exam:

- Inspect for swelling or nodule over the flexor tendon sheath at the base of the affected finger on the palm side

- Check the range of motion – flexion may be normal but the extension may be limited

- Palpate the tendon sheath for tenderness, thickening, and a palpable nodule/catching

- May reproduce triggering by having the patient repeatedly flex and extend a finger

- Check for any deformity of the digit

- Assess grip strength bilaterally

- Check for tenosynovitis of other digits

Evaluation:

- Clinical diagnosis is mostly made based on physical exam results and medical history.

- Imaging like an x-ray may be obtained to rule out other causes like arthritis, fracture, etc.

- Ultrasound can sometimes visualize the inflamed tendon sheath and nodule if a diagnosis is unclear

- May get labs like rheumatoid factor, ESR, CRP if inflammatory process suspected

- EMG/NCV is rarely needed unless suspecting nerve compression

- Diagnosis of exclusion – rule out other causes like arthritis, tendonitis, ganglion cyst

Non-Surgical Treatment

Here is the content rewritten by paraphrasing it and avoiding complicated words while maintaining the original meaning:

Cortico-Steroid Injection

Using corticosteroid injections is an effective way to reduce pain and decrease the frequency of the finger getting stuck or catching. A variety of steroids, such as triamcinolone, dexamethasone, or methylprednisolone, can be injected into the injured tendon. The choice of steroid can significantly impact the treatment outcome:

- For triamcinolone, patients often needed additional injections.

- For methylprednisolone, patients had surgery done earlier and more frequently.

The goal of the injection is to reduce inflammation and pressure on the tendon, allowing it to glide more smoothly through the pulleys. A primary care provider can safely and effectively administer these injections as an alternative to surgery. Compared to surgical treatment, steroid injections offer patient satisfaction, safety, and improved function.

Surgery is more costly, requires a longer time away from work, and carries potential surgical risks. Studies have also shown that combining a steroid injection with lidocaine is significantly more effective than using lidocaine alone.

Possible Side Effects

- Flare-up at the injection site

- Local infections

- Tendon ruptures

- Allergic reactions

- Thinning of the fat tissue under the skin

Situations to Avoid Injections

- Patients under 18 years old

- Any prior treatment or surgery in the same area within the last six months

- Symptoms potentially arising from an injury or tumor

Physical Therapy Management

In managing upper extremity disorders, it is essential to screen the proximal segments. In addition, addressing posture is crucial as it can impact distal issues and contribute to the patient’s overall outcomes.

Patient Education

Educating patients about the trigger finger, which is commonly caused by overuse, is of utmost importance. Patients should be informed about:

- Rest

- Adjustments in activities

- Utilization of specialized tools

- Splinting

- Modalities

- Posture

Splinting

When treating the trigger finger, the initial step involves discontinuing activities that worsen the condition. Splinting plays a vital role in restricting motion, modifying the biomechanics of the flexor tendons, and facilitating optimal tendon glide.

Different authors may have varying opinions on which joints to include in the splint and the extent of joint positioning. The choice of splinting method ultimately depends on what brings the patient the most relief. Typically, splints are worn for 6-10 weeks.

Authors may suggest different recommendations for splint positioning, such as positioning the MCP joint at 0 degrees and allowing full DIP joint movement. It should be noted that in patients with severe triggering or long-standing symptoms, the success rates of splinting may be lower.

Recent studies have focused on two main types of splinting techniques:

- Splinting at the DIP joint has shown a 50% reduction in symptoms for patients.

- Splinting at the MCP joint with 15 degrees of flexion, resulted in a significant 92.9% decrease in symptoms for patients.

Night splinting of the affected finger for 6 to 9 weeks has been found to improve patient compliance compared to continuous splinting. For patients with grade 1 and 2 Trigger Fingers, wearing a night splint for six weeks demonstrated a resolution of symptoms in 55% of cases for less than three months.

Exercises

Engaging in targeted exercises and stretches can effectively reduce trigger finger symptoms and enhance flexibility. To get the best outcomes possible, consistency is crucial.

The inflammation associated with the trigger finger often results in pain, tenderness, and restricted movement. Additional symptoms may include:

- Warmth, rigidity, or persistent pain around the affected thumb or finger base

- A protrusion or swelling at the finger’s base

- A sound that sounds like popping, clicking, or snapping when the finger is moved.

- Difficulty straightening the finger post-bending

Both hands and several fingers may be affected at once by these symptoms. When holding something or straightening a finger, they could be more apparent in the morning.

How to Getting Started

These are straightforward exercises that can be performed anywhere. All you require are an elastic band and small objects such as coins, bottle tops, and pens.

Dedicate at least 10 to 15 minutes daily to these exercises. Increase the length gradually as your strength increases. Increase the number of sets and repetitions as you see fit.

It is acceptable if you cannot complete the full range of motion for the exercises. Only engage in what is manageable. It’s acceptable to stop the workouts for a few days or until you feel better if your fingers become sore.

Extension Stretch for Fingers

- Place your hand flat on a table or steady surface.

- With the other hand, hold the afflicted finger.

- Slowly elevate the finger while keeping the other fingers flat.

- Gently raise and extend the finger as far as comfortable without overexerting.

- Maintain this position for a few seconds, then lower it back down.

- Repeat this stretch for all fingers and your thumb.

- Complete 1 set of 5 repetitions.

- Repeat this exercise 3 times daily.

Finger Spreading Exercise 1

- Position your hand in front of you.

- Extend the affected finger alongside a healthy finger.

- Use the thumb and index finger of your opposite hand to softly press the extended fingers together.

- Apply some resistance with your index finger and thumb as you separate the two fingers.

- Hold this position briefly and return to the initial posture.

- Perform 1 set of 5 repetitions.

- Repeat this routine 3 times each day.

Finger Spreading Exercise 2

- Move the affected finger away from the nearest normal finger to create a V shape.

- Press these two fingers against the others using your opposite hand’s index finger and thumb.

- Then, bring the two fingers closer together by pressing them against each other.

- Complete 1 set of 5 repetitions.

- Repeat this sequence 3 times daily.

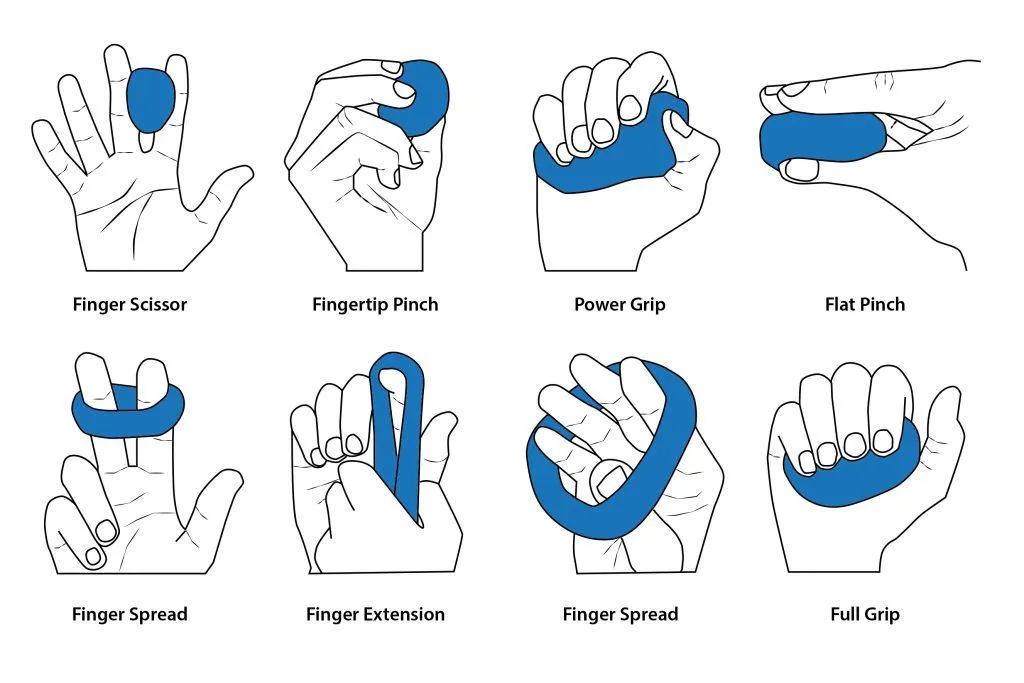

Stretching the Fingers

- Start by gently pinching your fingertips and thumbs together.

- Place a rubber band around your fingers.

- Slowly widen the gap between your fingers and thumbs, causing the band to tighten.

- Repeat this movement of extending and bringing your fingers and thumb close together 10 times.

- You should feel a slight stretch from the band during this exercise.

- Next, curl your fingers and thumb towards your palm.

- Loop the rubber band at the center.

- With your other hand, pull the end of the band to create a gentle tension.

- Maintain the tension as you flex and extend your fingers 10 times.

- Repeat this process at least three times throughout the day.

Pressing the Palm

- Take a small object and hold it in your palm.

- Squeeze the object tightly for a few seconds.

- Then release by opening your fingers wide.

- Repeat this a few times.

- Practice this exercise with different objects at least twice more during the day.

Picking Up Objects

- Arrange various small objects such as coins, buttons, and tweezers on a table.

- Pick up each object one by one using your affected finger and thumb.

- Transfer the objects to the opposite side of the table.

- Repeat this process for 5 minutes, twice a day.

Grasping Paper or Towel

- Take a paper sheet or small towel and place it in your palm.

- Use your fingers to crumple and squeeze the paper or towel into a small ball.

- Squeeze tightly and hold for a few seconds.

- Slowly release and straighten your fingers, letting go of the paper or towel.

- Do this workout twice a day for ten repetitions.

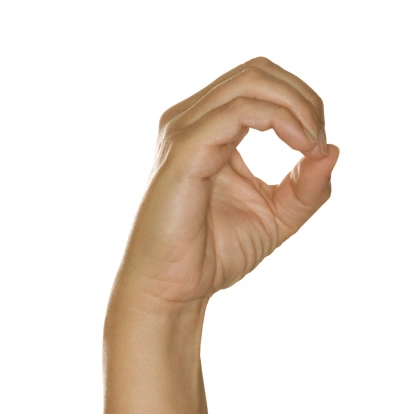

‘O’ Finger Exercise

- Bring the impacted finger towards your thumb to create a circle shape like the letter “O”.

- Maintain this position for 5 seconds.

- Subsequently, extend your finger and return it to the circular shape.

- Repeat this sequence 10 times, at least twice daily.

Finger and Hand Opening Routine

- Commence by lightly rubbing the base of the affected finger.

- Proceed to clench your fingers into a fist.

- Spend 30 seconds opening and closing your fist.

- Then, straighten the affected finger and return it to your palm.

- Continue this motion for 30 seconds.

- For two minutes, switch between these two workouts.

- Perform this routine three times each day.

Tendon Glide Exercise

- Extend your digits to their maximum length.

- Bend your fingers so the tips touch the top of your hand.

- Straighten your fingers and widen them.

- Subsequently, bend your fingers to reach the middle of your palm.

- Expand your fingers again.

- Bring the tips to the bottom of your palm.

- Then, touch each fingertip with your thumb.

- Have your thumb touch different spots on your palm.

- Complete 3 sets twice a day.

Finger Stretching Regimen

- Spread your fingers wide for a few seconds.

- Bring your fingers together tightly.

- Curve all your fingers backward and then forward.

- Position your thumb upright and gently pull it back for a few seconds.

- Repeat each stretch multiple times.

- Perform these stretches at least twice daily.

Remember to include self-massage in your routine!

It is recommended to incorporate self-massage into your trigger finger treatment plan. You can do this for short periods during the day.

It is particularly helpful to massage the finger affected by the trigger finger both before and after doing exercises. Massaging can improve blood circulation, flexibility, and range of motion.

Here are some steps to follow:

- Gently massage or rub in a circular motion.

- Apply gentle but firm pressure.

- Massage the entire area affected by the trigger finger or focus on specific points.

- Hold and press each point for approximately 30 seconds.

- Consider massaging your entire hand, wrist, and forearm, as they are interconnected. Choose the method that feels most comfortable and yields the best results.

Various other approaches

Therapies such as heating or icing, ultrasound, electrical stimulation, massage, gentle exercises, and moving the joints (both actively and passively) can yield positive outcomes for the trigger finger. It is believed that heat may enhance blood circulation and flexibility in the tendon. Stretching post-heat application can further enhance flexibility through plastic deformation. Furthermore, gentle joint movements and mobilizations enhance joint and soft tissue flexibility through slow, passive therapeutic traction and smooth gliding.

While the scientific evidence is limited, there are documented instances and studies demonstrating improvement with different combinations of these methods:

- A group of 74 patients underwent treatment involving ten sessions of wax therapy, ultrasound, muscle stretching exercises, and massage. Three months later, 68.8% of patients reported no pain or triggering symptoms. Among this group, none experienced pain or triggering after six months.

- 60 trigger thumbs in 48 children were daily treated with passive thumb exercises by their mothers. This approach resulted in an 80% cure rate for stage 2 trigger thumbs and a 25% cure rate for stage 3 thumbs after an average of 62 months.

Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy

Recently, there has been an advancement in the medical field with extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT), proposed as an alternative to surgery for musculoskeletal disorders in patients not responding well to traditional treatments.

Yildirim and his team conducted a study comparing ESWT with corticosteroid injection for trigger finger treatment. They discovered that three sessions of ESWT could be just as effective as a corticosteroid injection in improving symptoms and functionality for patients with grade 2 trigger fingers. Patients treated with ESWT received 1000 shocks at a frequency of 15 Hz, with significant improvements shown after the treatment period.

It is believed that ESWT aids in tissue repair and reduces inflammation in soft tissues through the stimulation of nitric oxide synthase. Additionally, it may help in addressing flexor tendon thickening and sheath obstruction in trigger finger cases. Research suggests that ESWT can lead to reduced pain, severity, and functional impact of triggering lasting up to 18 weeks post-treatment.

In conclusion, extracorporeal shock wave therapy is recommended as a non-invasive intervention without significant complications for patients with trigger fingers. It serves as an option for individuals who cannot undergo corticosteroid injections due to possible complications, allergies to local anesthetics, or fear of injections.

Operative Management

Open Surgical Technique

When conservative therapies are unsuccessful, surgery becomes necessary. The traditional open surgery, in combination with appropriate rehabilitation, leads to a rapid and significant enhancement in hand function with minimal risks of complications.

This approach, known as the gold standard, involves making a longitudinal incision in the palm crease above the metacarpophalangeal joint of the affected finger, followed by the release of the flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus tendons.

The duration of this procedure typically ranges from 2 to 7 minutes, with an average post-operative discomfort period of 45 days. One of the benefits of this method is the ability to visualize the pulley, which reduces the risk of damaging the digital nerves compared to endoscopic techniques.

Endoscopic Surgical Technique

Using this technique, two incisions are made: one at the finger’s volar crease and the other at the palm crease above the metacarpophalangeal joint. An endoscope is then used to cut the pulley and release the flexor tendons.

The procedure usually lasts between two to nine minutes, with a shorter average post-operative discomfort period of 23 days. Additional advantages include the absence of visible scars, reduced scar-related complications, and a shorter rehabilitation phase after surgery.

The endoscopic release provides comprehensive visualization while minimizing soft tissue damage and ensuring a precise release. However, its popularity is limited due to the steep learning curve required and the expenses associated with the necessary equipment.

Percutaneous Release

This technique can be carried out with or without imaging guidance. A non-image-guided percutaneous release, also known as blind release, relies on anatomical landmarks to prevent harm to tendons and neurovascular structures.

While the recovery time is shorter than open surgery, there is an increased risk of damaging the digital nerves, especially in fingers 1, 2, and 5. A novel technique using ultrasound guidance aids in identifying tendons and neurovascular structures, thereby reducing the likelihood of complications associated with blind percutaneous release. It also yields comparable results to surgical methods.

Home Remedies

- Rest and Immobilization: Resting the affected hand and avoiding activities that aggravate the condition can help reduce inflammation. Splinting or taping the finger in a straight position, especially at night, can prevent it from getting stuck in a bent position.

- Ice Therapy: Reducing swelling and inflammation in the tendon sheath area can be achieved by applying ice packs or cold compresses to the base of the afflicted finger.

- Over-the-Counter Medications: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen or naproxen can help alleviate pain and inflammation associated with the trigger finger.

- Stretching and Exercises: Mild stretches and finger exercises can assist improve the range of motion and reduce stiffness. However, it’s important to avoid overexerting the finger.

- Massage: Gently massaging the base of the affected finger and the palm area can help improve circulation and promote healing.

- Warm Compresses: Applying a warm compress to the area before stretching or massaging may help increase blood flow and relax the muscles and tendons.

It’s important to note that while home remedies can provide temporary relief, they may not address the underlying cause of the trigger finger. If symptoms persist or worsen, it’s recommended to seek medical attention for proper diagnosis and treatment.

Prevention Strategies

- Take Breaks and Stretch: If your job or activities involve repetitive gripping or flexing of the fingers, take frequent breaks to stretch and extend your fingers fully. This helps reduce the strain on the finger tendons and sheaths.

- Practice Finger Exercises: Perform gentle exercises to keep the fingers flexible and mobile. For example, make a tight fist and then slowly extend the fingers as far as possible, holding the stretch for 5-10 seconds.

- Use Proper Gripping Technique: When gripping objects, avoid crimping or curling your fingers tightly. Keep a straighter wrist position and use an open palm grip when possible to reduce tendon stress.

- Modify Activities or Tools: If certain activities aggravate your symptoms, modify them or use tools/equipment that put less strain on your hands and fingers.

- Manage Underlying Conditions: Certain medical conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and gout increase the risk of a trigger finger. Managing these conditions properly can help prevent complications.

- Maintain Healthy Weight: Excess weight can put additional strain on the joints and tendons in the hands and fingers, increasing the risk of developing trigger fingers.

- Strengthen Hand Muscles: Exercises to strengthen the muscles in the hands and forearms can help support and stabilize the finger tendons during gripping activities.

- Use Proper Ergonomics: Ensure your workstation is set up ergonomically to maintain proper wrist and hand positioning during tasks that involve repetitive finger movements.

Early preventive measures can help reduce the risk of developing a trigger finger or prevent it from progressing further if it does occur.

Summary

Trigger finger, also known as stenosing tenosynovitis, is a condition that causes one of the fingers or the thumb to catch or lock in a bent position. It occurs when inflammation narrows the sheath that the tendon moves through, making it difficult for the tendon to glide smoothly.

The main symptom is the inability to straighten the affected finger or thumb, especially in the morning. As the finger moves, it may straighten with a pop or click after being stuck in a bent position. Over time, the catching or locking can become more frequent and severe.

Trigger finger is often caused by repetitive hand movements or gripping actions that irritate the tendon sheath. It’s more common in women and those with certain medical conditions like rheumatoid arthritis or diabetes. Sometimes, though, the precise cause is not known.

The severity of the ailment determines the available treatment options. For mild cases, resting the hand, taking anti-inflammatory medication, and wearing a splint at night may help. Steroid injections into the tendon sheath can reduce inflammation and allow smoother tendon movement. If non-surgical treatments fail, a simple outpatient surgical procedure may be recommended to open the constricted tendon sheath.

Early treatment is essential to prevent further tendon damage and permanent finger immobility. With proper management, trigger finger is often treatable, and normal finger mobility can be restored. However, it’s essential to address any underlying conditions contributing to the problem.

FAQs

What is a trigger finger?

Trigger finger, also called stenosing tenosynovitis, is a condition where one of the fingers or the thumb gets stuck in a bent position. It occurs when inflammation makes it difficult for the tendon to glide smoothly through the sheath.

What causes a trigger finger?

The exact cause is unknown, but it’s often related to repetitive hand movements that irritate the tendon sheath. It can also occur with certain medical conditions like rheumatoid arthritis or diabetes.

What are the symptoms?

The main symptoms are the finger catching or locking in a bent position, difficulty straightening it, a popping or clicking sensation when straightening, and swelling or a bump at the base of the affected finger.

How is it diagnosed?

Trigger finger is typically diagnosed based on a physical exam and the patient’s description of symptoms. Imaging tests like X-rays or ultrasounds may be done to rule out other conditions.

What are the treatment options?

Mild cases may respond to rest, splinting, and anti-inflammatory medication. Steroid injections into the tendon sheath can reduce inflammation. If these don’t work, surgery to open the tendon sheath may be recommended.

Is surgery always required?

No, surgery is usually only recommended if non-surgical options like injections or splinting fail to provide relief after a few months.

Can the trigger finger be prevented?

Taking breaks from repetitive gripping activities, doing finger stretches, and treating any underlying medical conditions may help prevent trigger fingers.

What is the recovery time after treatment?

With non-surgical treatments, recovery can take several weeks or months. After surgery, it typically takes 4-6 weeks to fully recover and regain finger mobility and strength.

References

- Trigger finger – Symptoms and causes – Mayo Clinic. (2022, December 3). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/trigger-finger/symptoms-causes/syc-20365100

- Trigger Finger: What is? Symptoms, Causes, & Treatment | The Hand Society. (n.d.). https://www.assh.org/handcare/condition/trigger-finger

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Trigger Finger. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/7080-trigger-finger#management-and-treatment

- Jeanmonod, R., Harberger, S., & Waseem, M. (2023, July 17). Trigger Finger. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459310/

- Seed, S. (2003, December 3). Trigger Finger. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/rheumatoid-arthritis/trigger-finger

- Trigger Finger. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Trigger_Finger

- Cht, A. B. P. D. (2023, December 7). Treatment for Mild to Severely Locked Trigger Finger. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/trigger-finger-treatment-8400803

- Cronkleton, E. (2023, February 6). 11 Trigger Finger Exercises to Try at Home. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/fitness-exercise/trigger-finger-exercises#massage

One Comment