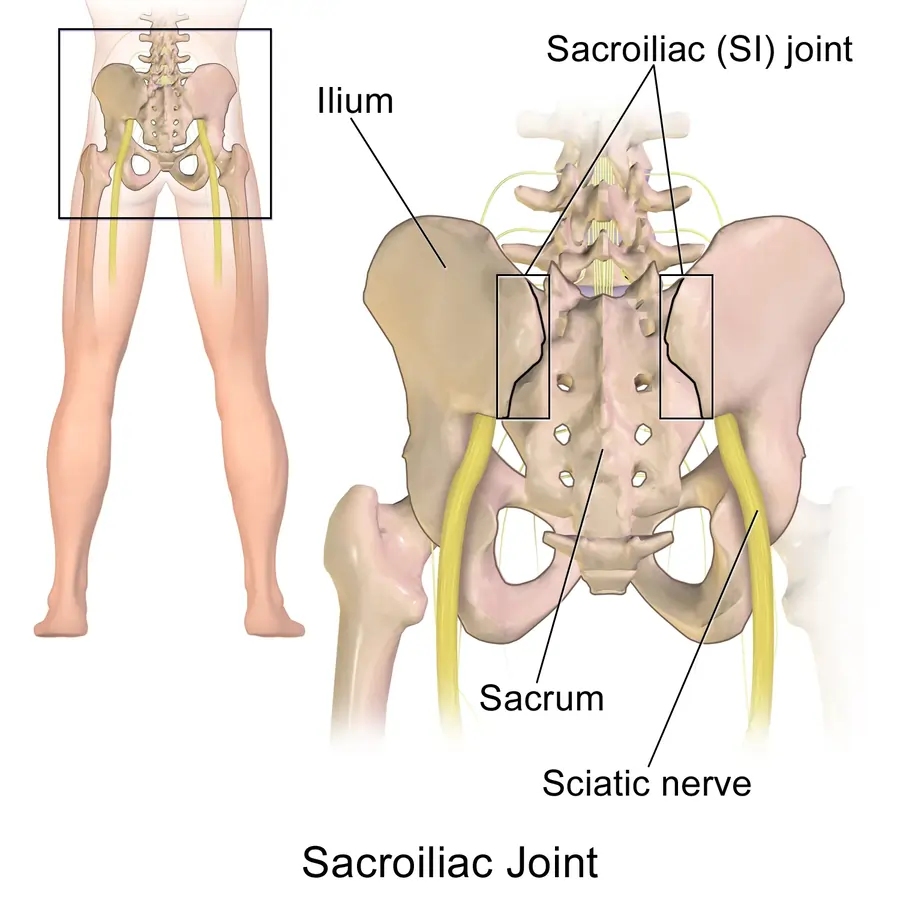

Sacroiliac Joint

The sacroiliac (SI) joint joins the sacrum at the base of the spine to the pelvic ilium by the sacroiliac (SI) joint. It plays a crucial role in transferring weight and force between the upper body and the lower limbs while providing stability and shock absorption.

SI joint dysfunction can cause lower back, buttock, or leg pain, which frequently simulates other disorders, including lumbar disc pathology. Accurate assessment and targeted treatment are essential for managing SI joint-related issues effectively.

Introduction

The junction between the pelvic ilium and sacrum, which are joined by robust ligaments, is known as the sacroiliac joint or SI joint (SIJ). In humans, the sacrum, which is supported by an ilium on either side, also supports the spine. The robust joint supports the entire weight of the upper torso.

The two bones interlock at this synovial plane joint because of their asymmetrical elevations and depressions. There are two sacroiliac joints in the human body, one on the left and one on the right. These joints frequently match, although they differ greatly from person to person.

Structure

The articular surfaces of the sacrum and the ilium bones produce paired C-shaped or L-shaped joints called sacroiliac joints. These joints have a limited range of motion (2–18 degrees; however, this is currently up for debate). However, the majority concur that these joints barely move, with a range of motion of only 3 degrees during flexion extension, 1.5 degrees during axial rotation, and 0.8 degrees during lateral bending.

The two types of cartilage that cover the joints are fibrocartilage on the iliac surface and hyaline cartilage on the sacral surface. The stability of the SIJ is primarily preserved by a combination of powerful intrinsic and extrinsic ligaments and relatively little bony tissue. Typically, the joint gap is between 0.5 and 4 mm.

The sacroiliac joint’s properties alter with age. Early in life, the joint’s surfaces are flat or planar. The surfaces of the sacroiliac joints lose their flat or planar topography and start to take on unique angular orientations as walking ability develops.

A depression forms along the sacral surface, and a raised ridge forms along the iliac surface. The powerful ligaments and the ridge and matching dip strengthen the stability of the sacroiliac joints and reduce the likelihood of dislocations. The fossae represent the superficial morphology of the sacroiliac joints lumbales laterales, or “dimples of Venus”.

Articulation, Location, and Shape

The sacroiliac joint is formed by the articulation of the inner side of the butterfly-shaped hip bone (ilium) and the outer side of the sacrum of the spine.

- The SI joints are located deep within the pelvis, on either side of the sacral spine.

- Strong ligaments hold each SI joint in place and provide excellent protection.

- The joint surface runs from the middle of the S3 spinal segment to the S1 spinal segment. Beginning above the S1 spinal segment (close to the L5-S1 or lumbosacral joint) and concluding near the top of the S3 spinal segment, this location may vary slightly.

From the front, the joints on either side of the lower spine are parallel to one another.

If the sacroiliac joint is swollen (sacroiliitis) or not working normally (sacroiliac joint dysfunction), pressing the skin directly over it in the back of the pelvis may cause pain.

Articular Surface

The spine and pelvis are connected by the special sacroiliac articulation between the sacrum and the hip.

Although the SI joint possesses the characteristics of a normal movable joint, its internal movements are extremely restricted.

The sacroiliac joint is C-shaped.

A fully grown adult sacroiliac joint is made up of two layers of bone that are C-shaped (or inverted L-shaped) and have some irregular ridges and depressions.

- The convex outer portion of the C represents the ilium bone of the hip. The hyaline cartilage covering this surface is thick.

- The fused sacral bones S1–S3 are represented by the inner (concave) portion of the C. Thin fibrocartilage lines this surface.

- Due to their innate ability to adapt to stress, both types of cartilage in the sacroiliac joint have a rough, coarse texture.

- These opposing joint surfaces articulate near one another.

- Three regions on the joint surface correspond to the sacral vertebrae. The largest area is close to S1, while the smallest joint surface is close to S3.

As the connecting surfaces age, their angle and texture slightly alter to counteract and withstand compression and forces in this area. As people age, the ridges and depressions that form along the surfaces of the joints deepen.

Joint Capsule

- A diarthrodial synovial joint is the SIJ.

- Enclosed by a fibrous capsule, the joint area between the articular surfaces is filled with synovial fluid.

- Two robust, C-shaped layers make up the articular surface.

- It is unique in that it has two distinct types of cartilage that articulate differently than other synovial joints.

- Hyaline cartilage, the weakest type of cartilage and one that is made of type II collagen makes up the sacral capsular surface.

- Fibrocartilage makes up the iliac capsular surface; it is the strongest kind of cartilage and is derived from type I collagen.

Ligaments

The SI joint is stabilized by a robust ligamentous structure.

The main link between the sacrum and the ilium is formed by the interosseous sacroiliac ligament. It is the body’s strongest ligament that stops the sacrum from moving anteriorly or inferiorly.

- The anterior sacroiliac ligament is a weak, thin, and anteroinferior thickening of the fibrous capsule to the other ligaments of the joint. It connects the lateral side of the preauricular sulcus to the third sacral ligament and is more developed around the PSIS and the arcuate line. Due to its thinness, this ligament is frequently torn and causes pain.

- The strong, short interosseous sacroiliac ligament, which extends deep to the posterior sacroiliac ligament, serves as the primary link between the sacrum and the innominate. It prevents the sacrum from moving anteriorly or inferiorly.

- The PSIS is connected to the lateral crest of the third and fourth segments of the sacrum via the posterior (dorsal) sacroiliac, which is incredibly strong and resilient. The ligament is loosened by nutation, or anterior sacral motion, and tautened by counternutation, or posterior sacral motion. It frequently causes pain and is palpable just below the PSIS.

- The posterior (dorsal) sacroiliac ligament is merged with the sacrotuberous, which is made up of three large fibrous bands. During weight bearing, it stabilizes the sacrum against nutation and prevents the sacrum from migrating posteriorly and superiorly.

- Sacrospinous: Thinner than the sacrotuberous ligament, it has a triangular shape and extends laterally from the ischial spine to the lateral portions of the sacrum and coccyx. It prevents the sacrum on the innominates from tilting forward when weight is supported, along with the sacrotuberous ligament.

The sacroiliac joint is connected in multiple ways by its stabilizing and supporting ligaments. Some ligaments hold the joint surfaces together, whereas others connect the joint from the front and back.

Interosseous sacroiliac ligament

Among the strongest ligaments in the body is the interosseous ligament. It supports lower body movement and stabilizes the torso while bearing heavy loads.

The ligament between the bones:

- Attaches the ilium (hip bone) to the sacrum’s (the lower spine’s triangle) outer surface.

- The ligaments connected to the sacroiliac joint are subjected to intense strain.

- Enables the sacrum and ilium to form their main connection.

- Stops the sacrum from moving below and forward.

- Prevents excessive rearward movement, protecting the joint.

The interosseous ligament is composed of many layers. This ligament aids in preventing harmful motions of the sacroiliac joint toward the back since the rear part of the joint is not enclosed by a capsule like the front.

Superior intracapsular ligament (Illi’s ligament)

This ligament is a thin, sometimes absent band of fibrous tissue. The Illi’s ligament has little to no mechanical importance and is believed to be an extension of the interosseous ligament.

Anterior sacroiliac ligament

This ligament, also known as the ventral sacroiliac ligament, protects the articular (joint) capsule that surrounds the sacroiliac joint in this region. The fibers in this capsule do not offer much support since they mix in with the capsule in front of the joint.

The anterior SI ligament is particularly prone to pain and injury because of its relative thinness.

Posterior sacroiliac ligament

Along the rear of the sacroiliac joint, the posterior SI ligament offers significant support. The ligament joins the sacrum to the rear of the hip bones, which are the iliac crest and posterior-superior iliac spine.

The posterior SI ligament is made up of two parts:

- Long posterior sacroiliac ligament

- Short posterior sacroiliac ligament

Tension is experienced by the long posterior sacroiliac ligament when forces are transferred from the legs to the upper torso and vice versa.

Accessory sacroiliac ligaments

The three auxiliary ligaments listed below contribute to the sacroiliac joint’s increased stability.

- Sacrotuberous ligament

- Sacrospinous ligament

- Iliolumbar ligament

The greater sciatic foramen and the lesser sciatic foramen are formed by the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments. The bigger sciatic foramen created by these ligaments is where the sciatic nerve, the biggest nerve in the body, travels through. Sciatic nerve discomfort, which travels down the leg along the nerve’s path, can result from injury to these ligaments and the inflammation that follows.

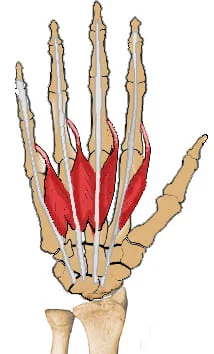

SI Joint Muscles

The majority of the sacroiliac joint’s motion is made possible by strain on its ligaments rather than the muscles surrounding it.

Usually, the nearby muscle groups contribute to preserving the stability and functionality of this crucial joint.

Anatomically, more than 40 muscles encircle the SI joint. The SI joint is primarily impacted by the following muscle groups:

- The erector spinae, quadratus lumborum, and multifidus lumborum are examples of back muscles.

- Hip muscles, such as the iliopsoas.

- Rectus abdominis and other core muscles.

- Buttock muscles, including the piriformis and gluteus maximus.

- The hamstring group’s biceps femoris is one of the thigh muscles.

These muscles get shorter when they are underactive (due to a sedentary lifestyle, for example), which puts strain on the sacroiliac joint and makes it stiff. When these muscles are properly stretched and activated, the joint can be made flexible and pain-free.

Blood Supply of the Sacroiliac Joint

The sacroiliac joint is supplied by a dense network of arteries that run along its front and rear in both large and tiny branches.

- The median sacral artery and lateral sacral artery supply blood to the rear part of the joint. Commonly located at the L5-S2 levels of the spine, the internal iliac artery is the source of both of these arteries. The superficial branch of the superior gluteal artery connects to these arteries.

- The iliolumbar artery, which can come from the internal or common iliac arteries, supplies blood to the front part of the joint.

The internal iliac vein receives the joint’s venous drainage.

The ligaments and/or cartilage of the sacroiliac joint are impacted by the great majority of these issues. Muscles that surround the SI joint, including the thigh, back, core, and buttocks, can potentially affect the joint if they are tight and poorly trained. Age-related changes in the joint’s mechanical loading pattern and natural development allow for increasing physiological stressors and effects on the hip and pelvic areas.

Innervation

Though clinically implicated in lumpopelvic pain, the SIJ’s innervation has not been fully investigated. There have been reports of innervation by branches from the ventral lumbopelvic rami (Ikeda, 1991), but this has not been confirmed.

However, many authors have documented that the SIJ is innervated by small branches from the posterior rami. In 1974, Bradley discovered that the joint was innervated by fine fibers from L5 to S3, but Grob et al. (1995) reported that the posterior rami S1–S4 were branches to the joint. In the ligaments close to the joint, McGrath & Zhang (2005) reported fine fibers from S2 to S4 and infrequently S1, and Willard et al. (1998) were able to trace small branches from a communicating branch of L5, as well as from S1 and S2, into the joint’s edge.

Patel et al.. (2012) reported a satisfactory reduction in SIJ pain with neurotomy of the L5 dorsal main ramus and lateral branches of the dorsal sacral rami from S1 to S3. Dichotomizing axons from neurons of the dorsal root ganglion at levels L1–L6 have been shown to exist in rats using double-labeling techniques (Umimura et al. 2012). These axons send branches to the multifidus muscle and the SIJ, indicating a potential mechanism for lower back pain that is referred to.

The joint contains both myelinated and unmyelinated fibers as well as encapsulated endings (Grob et al., 1995). The nerves leading to the SIJ had several axons with sizes ranging from 0.2 to 2.5 mm, placing them well within the group IV (C-fiber) fiber range and maybe into the smaller end of the group III (A-delta) fiber range (Ikeda, 1991). The majority of the fibers are high-threshold, group III in nature, according to electrophysiological recordings made from the axons innervating the cat SIJ (Sakamoto et al. 2001).

The cartilage on both sides of the joint and the surrounding ligaments have small fibers that are positive for substance P and calcitonin gene-related polypeptide, but the subchondral bone did not have a significant quantity of these fibers (Szadek et al.. 2008, 2010). Pain perception from the SIJ is probably mediated by axons of this size and with these physiological characteristics, which have been linked to nociception in other regions.

Small fibers entering the SIJ along its medial and inferior boundaries were shown in a study that used gross dissection and fluoroscopic imaging of tiny metal wires placed on the lateral branches of the dorsal sacral plexus. The study also showed evidence that these fibers may be connected to pain patterns observed in a subset of LBP patients (Yin et al.. 2003). These studies demonstrate that, at the very least, the posterior primary rami of the lower lumbar and upper sacral segments innervate the joint’s outer border.

Function

Along with converting torque so that transverse rotations in the lower extremities can be transmitted up the spine, the SI joints, like the majority of lower extremity joints, also serve as shock absorbers for the spine, depending on the range of motion at the sacroiliac joint.

The pelvis transfers the body weight from the sacrum to the hip bone, and as weight is transferred from one leg to the other, the joint locks (or rather becomes densely packed) on one side.

The sacroiliac joint’s movements

- Both hip bones’ anterior innominate tilt on the sacrum, where the left and right move together

- Both hip bones’ posterior innominate tilt on the sacrum, where the left and right move in unison

- An antagonistic innominate tilt, which happens during locomotion, is when one innominate bone tilts anteriorly while the other tilts posteriorly on the sacrum.

- Sacral nutation or flexion The sacrum and ilium move simultaneously, thus, it’s important to be cautious when describing them as separate motions.

- The sacral extension is often known as a counter-nutation.

The sacroiliac joints are bicondylar, which means that when one side moves, the other side moves in proportion. This is true of all spinal joints except the atlanto-axial.

The Function of Sacroiliac Joints: Mobility, Shock Absorption, and Stabilization

The sacroiliac joints perform several essential roles, including:

- Regulate and disperse the forces between the upper and lower body.

- It serves as a spine’s shock absorber and regulates how forces from the lower body, such as gravity and forces transferred upward during standing or walking, are transferred into the spine.

- Permit ambulation, thigh and spinal motions, and positional or posture changes, including standing to sitting and lying to standing.

- Support the upper body’s weight.

- Make women’s pregnancies and deliveries easier by expanding and increasing their mobility.

This joint’s connections to the nervous system relay pain signals that originate in the joint and the ligaments that surround it. A sense of position and balance is also provided by the nerves.

Movement

The sacroiliac joint primarily moves anteriorly and posteriorly, or front and back. Additionally, movements take place along various planes, including upward and downward. Movements can be categorized further into:

- Nutation is the term used to describe the sacroiliac joint’s forward and downward (anterior-inferior) movement. This motion involves the coccyx, or the tailbone, moving back to the hip bone. Two The nutation movement increases the stability of the sacroiliac joint.

- Counternutation is the term for the joint’s upward and backward (posterior-superior) movement. During this motion, the tailbone propels forward relative to the hip bone.

These motions are usually restricted to 2 mm to 4 mm and 2° to 5° because of the joint’s surrounding ligaments and bony structure.

When the hip’s extremes are reached, the sacroiliac joint exhibits its full range of motion (e.g., when rotating the hip outward until the farthest point).

Factors that Influence SI Joint Movements

The sacroiliac joint’s movements are influenced by factors such as age, sex, and the mechanical loads applied to it. For instance:

- Athletes, women (during pregnancy and childbirth), and younger individuals may need the most mobility in their sacroiliac joints.

- Older people, people who are overweight, and people who regularly carry heavy weights may need more stability. The joint’s robust ligaments and age-related ridges and depressions along the joint surfaces may be able to accommodate this increased need for stability by improving interlocking.

During pregnancy, this joint also undergoes adaptive changes as the joints become more mobile to accommodate the expanding pelvis and growing uterus.

Age-Related Changes in the SI Joint

The aging process naturally causes changes in the sacroiliac joint’s bones.

More forces can be accommodated by the sacroiliac joint, thanks to these modifications. As an illustration:

- There is an increase in joint stability. As a person enters early adulthood and nears the end of adolescence, the ligaments play a major role in maintaining the stability of the joint. Adulthood improves stability by strengthening the bony interlockings on the joint surface.

- The joint’s mobility has diminished. Around the eighth decade of life, the sacroiliac joint’s range of motion typically diminishes as people age.

Injection treatments, like sacroiliac joint injections, become more difficult as the joint ages because the space between the joining bones gets smaller.

A condition known as sacroiliac joint dysfunction may be indicated if the joint moves more or less than usual as a result of an underlying issue and produces symptoms.

Clinical Significance

Inflammation and dysfunction

Lower back pain can be caused by sacroiliitis, which is an inflammation of one or both sacroiliac joints. Depending on the degree of inflammation, a person with sacroiliitis may feel pain in the thigh, buttock, or lower back.

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction, also known as SI joint dysfunction or SIJD, is a common term used to describe mechanical issues of the sacroiliac joint. Sacroiliac joint dysfunction is the general term for pain in the sacroiliac joint area caused by either excessive or insufficient sacroiliac joint motion. This usually leads to sacroiliitis or inflammation of the SI joint.

Signs and symptoms

An SI joint (SIJ) issue may be accompanied by the following symptoms and indicators:

- Unilateral dull low back pain is typically the result of mechanical SIJ dysfunction.

- The dimple or posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) area is frequently the site of mild to moderate pain.

- When performing tasks like getting out of a chair or raising the knee to the chest while stair climbing, the pain may intensify and become more acute.

- Though it can occasionally be bilateral, PSIS pain is usually unilateral, affecting only one side.

- Severe SIJ dysfunction pain, which is uncommon, can radiate into the hip, groin, and sometimes down the leg. However, the pain hardly ever goes below the knee.

- From the SIJ, pain may radiate to the back of the thigh or buttock and, in rare cases, to the foot.

- Usually, unilateral, low back pain and stiffness that gets worse when you sit or walk for extended periods.

- Sexual activity can cause pain, but this is not limited to issues with the sacroiliac joints.

Provocative and nonprovocative techniques are used to test for sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Prone knee flexion, supine long sitting, standing flexion, seated flexion, and the Gillet test are non-provocative sacroiliac joint examination techniques. There is no proof that these mobility maneuvers for the sacroiliac joints can identify abnormal motion.

Provocative maneuvers are a broad category of clinical signs that have been described due to the inherent technical limitations of the visible and palpable signs from these sacroiliac joint mobility maneuvers. These movements are intended to replicate or intensify sacroiliac joint pain. Provocative maneuvers that replicate pain along the typical area raise the possibility of sacroiliac joint dysfunction. However, there isn’t a single test that can accurately diagnose sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Damage to the nervous system may manifest as weakness, numbness, or the loss of a corresponding reflex.

A sacroiliac joint injection performed with a local anesthetic solution and verified by fluoroscopy or CT guidance is currently the gold standard for diagnosing sacroiliac joint dysfunction that originates within the joint. When the patient reports a noticeable improvement in pain relief and the diagnostic injection is administered on two different occasions, the diagnosis is verified. According to published research, a response is deemed positive, and the sacroiliac joint is identified as the cause of pain when there is a minimum of 75% improvement in pain relief.

Pregnancy

The ligament support surrounding the SIJ may be compromised by the hormonal changes associated with menstruation, pregnancy, and lactation. For this reason, women frequently experience the worst pain in the days preceding their periods. Female hormones released during pregnancy facilitate the relaxation of the body’s connective tissues.

The female pelvis must relax for it to stretch sufficiently during delivery to accommodate childbirth. The SIJs are altered as a result of this stretching, becoming excessively mobile. These alterations may eventually result in wear-and-tear arthritis over many years. Naturally, a woman’s risk of SI joint issues increases with the number of pregnancies she has. Micro tears and tiny gas pockets may develop in the joint during pregnancy.

SIJ dysfunction can result from hormonal changes, trauma (such as falling on the buttock), and muscle imbalance. Anterior sacroiliac joint pain can be experienced, but it must be distinguished from hip joint pain.

Though there is currently no reliable evidence to support this theory, women are thought to experience sacroiliac pain more frequently than men, primarily due to structural and hormonal differences between the sexes. Instability may increase because female anatomy frequently permits one fewer sacral segment to lock with the pelvis.

FAQs

The sacroiliac joint: what is it?

The junction of the sacrum and ilium bones is known as the sacroiliac (SI) joint. It lies between the upper part of the pelvis and the base of the spine.

What is the underlying reason why SI joints malfunction?

Excessive mobility of the SI joint can be caused by the degeneration of the ligaments surrounding it or by injury to the ligaments. Excessive mobility can cause inflammation and damage to the joint and nearby nerves.

Can an SI joint be cured?

Physical therapy and anti-inflammatory drugs are two conservative approaches that can effectively treat a large number of sacroiliac joint pain cases. When SI joint discomfort is caused by another ailment, like osteoarthritis, its resolution may rely on the underlying condition’s ability to be healed.

What signs of sacroiliac joint pain are present?

The lower back, buttocks, hips, and legs can all be affected by sacroiliac (SI) joint pain. The discomfort can be subtle and achy or severe and stabbing.

References

- Wikipedia contributors. (2025c, February 7). Sacroiliac joint. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacroiliac_joint

- Bjerke, B., MD. (n.d.). Sacroiliac joint anatomy. Spine-health. https://www.spine-health.com/conditions/spine-anatomy/sacroiliac-joint-anatomy

One Comment