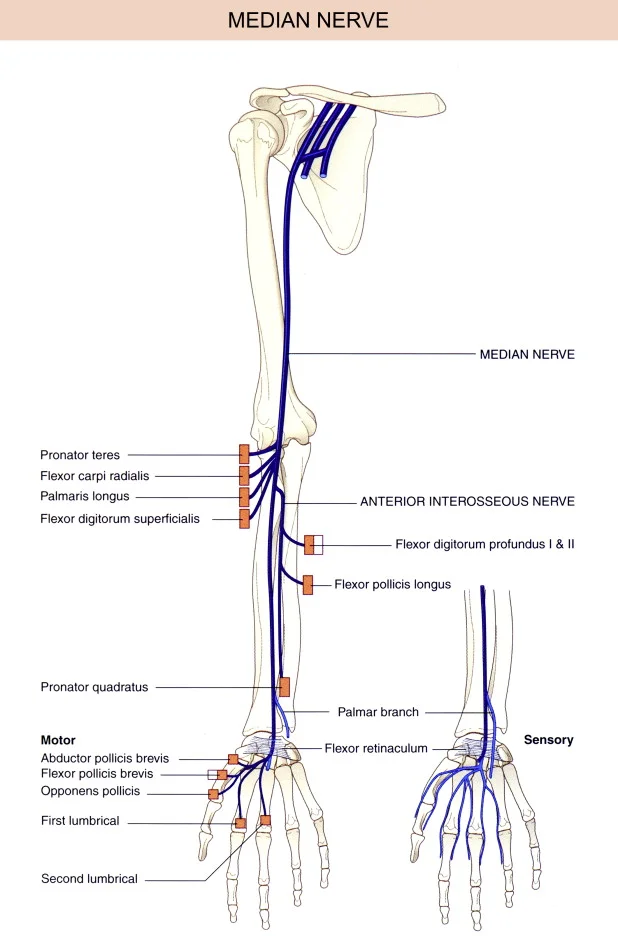

The median nerve is a major nerve of the upper limb, originating from the brachial plexus (C5-T1). It runs down the arm, forearm, and into the hand, providing motor innervation to most forearm flexor muscles and some hand muscles, and sensory innervation to the lateral palm, thumb, index, middle, and half of the ring finger.

Introduction

Another name for the median nerve is the “eye of the hand.”,’ is a mixed nerve that has a role of vital importance in the functioning of the hand. It controls the abduction of the thumb, the flexion of the hand at the wrist, and the flexion of the digital phalanx of the fingers. It innervates the group of flexor-pronator muscles in the forearm, and well as the majority of the musculature is found in the radial area of the hand. The thumb, index, middle, and ring fingers’ palmer faces, as well as the whole palmar region of the hand’s radial half, are sensory innervated. by the nerve. Additionally, it offers sensitivity to the dorsal skin of the index and middle fingers’ last two phalanges.

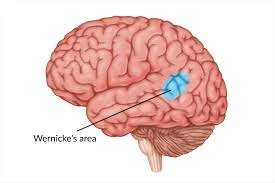

The nerve in the cervical area of the spinal cord originates from the medial and lateral cords of the brachial plexus. The ventral major rami of cervical nerve root five through eight and the first thoracic spinal segment are the origins of these cords. The median nerve descends medially to the brachial artery at the humeral level after entering the forearm between the two pronator teres heads. The nerve is quite superficial in the cubital fossa and extends deep to the bicipital aponeurosis. The flexor digitorum profundus is situated superficially to the median nerve in the forearm. and deep to the flexor digitorum superficialis.After that, it enters the palm under the flexor retinaculum, posterior to the palmaris longus tendon and lateral to the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon. Anywhere along its length, the median nerve is susceptible to pathology and damage.

Interestingly, none of the arm’s muscles are innervated by the median nerve. There are certain vascular branches of the median nerve that feed to the brachial artery, and articular branches of the median nerve innervate the elbow joint, even though Innervated proximal to the elbow joint is the branch to the pronator teres. The median nerve innervates the palmaris longus, flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor carpi radialis, pronator teres, flexor digitorum superficialis, and the medial portion of the pronator quadratus. in the forearm. Furthermore, the flexor pollicis longus and flexor digitorum profundus of the hand are innervated by the anterior interossei branch of the median nerve.

The carpal, radiocarpal, and distal radioulnar joints are all supplied by the median nerve’s articular branches. The ulnar nerve is connected to many connecting branches of the median nerve. The median nerve innervates the muscles of the palm’s thenar compartments, such as the flexor pollicis longus, abductor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, and adductor pollicis. Additionally, the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve innervates the skin over the two-and-a-half fingers over the dorsum of the hand, as well as the skin over the lateral two-and-a-half fingers and thenar eminences on the palmar side of the hand.

Acute traumatic, chronic microtraumatic and compressive lesions can all impact the median nerve. Neuropathies and degenerative processes with diverse causes can potentially harm the nerve. Along the median nerve’s lengthy journey from the brachial plexus and axilla to the hand, several kinds of lesions can impact it at different levels. Neuropathies mainly concern the distal territory. The flexor retinaculum’s fascial sheath may compress the median nerve peripherally, resulting in neuropathic pain, which is characterized by tingling, numbness, and burning sensation.

Entrapment or carpal tunnel syndrome are the names given to this ailment. The discomfort associated with carpal tunnel syndrome can be described as a pin-and-needle feeling along the median nerve’s distribution. The idiopathic disorder is linked to diabetes, hypothyroidism, and pregnancy. A medial nerve damage proximal to the carpal tunnel is indicated by decreased feeling across the patient’s thenar eminence. The palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve, which is located close to the carpal tunnel, provides the neural supply for the thenar eminence feeling. Clinically, flare-ups and remissions are possible for sporadic symptoms.

Structure & Function

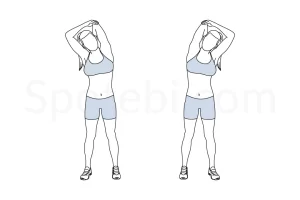

The flexor muscles of the hand and forearm get the majority of their motor innervation from the median nerve. Additionally, the dorsal side (nail bed) of the hand’s distal first two fingers, the palmar aspect of the thumb, index, middle, and half of the ring finger, the palm, and the medial part of the forearm are all sensory innervated by the median nerve.

Course of the Median Nerve

The median nerve travels distally along the median bicipital groove in a neurovascular bundle with the brachial artery after the confluence of the lateral and medial cords within the axilla. It passes beneath the bicipital aponeurosis, a sheath of connective tissue that inserts the biceps brachii to the proximal forearm, and across the brachial artery as it descends the arm, forming the cubital fossa. The median nerve does not innervate the muscles or skin above this point. Nonetheless, it gives the brachial artery and its farther-flung branches (radial and ulnar arteries) sympathetic innervation.

The pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, flexor digitorum superficialis (sublimes), and palmaris longus muscles are among the proximal muscle bellies of the forearm that get innervation from the median nerve when it passes beneath the bicipital aponeurosis at the elbow level. The nerve crosses the place where the superficial and deep heads of the pronator teres converge as it leaves the bicipital aponeurosis. Pronator syndrome, which is explained below, can result from compression at this stage. Before emerging to give off two branches, the anterior interosseous nerve and the median nerve proper, the median nerve makes its last pass beneath the sublime ridge, a sheath of connective tissue created by the convergence of the medial and lateral heads of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS).

The median nerve properly descends the forearm, passing superficially to the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) but deeply to the flexor digitorum superficialis. Just in front of the interosseous membrane, the anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) travels deeper than the median nerve proper. The pronator teres, palmaris longus, and flexor digitorum superficialis are innervated in the forearm by the median nerve proper. On the other hand, the AIN innervates the pronator quadratus, flexor pollicis longus, and FDP. By the conclusion of its journey through the forearm, the median nerve and all of its branches innervate every flexor muscle in the forearm, except for the ulnar portion of the flexor digitorum profundus and the flexor carpi ulnaris.

Fifth centimeters above the flexor retinaculum,

Just before entering the carpal tunnel, the median nerve anatomically rests between the flexor carpi radialis tendon and the muscular belly of the FDS, which terminates and transforms into a tendinous sheath. The palmar cutaneous branch, which crosses the flexor retinaculum and only supplies sensory innervation to the palm and the base of the thenar eminence, is produced by the median nerve at a variable position before the wrist.

The cross-sectional size of the carpal tunnel is less than 2 square centimeters at its narrowest point. Together with nine other muscle tendons, the median nerve travels right beneath the flexor retinaculum sheath. Compression is likely to occur in this high-traffic location, and carpal tunnel syndrome—which is explained below—is the most prevalent of entrapment neuropathies.

The thenar recurrent motor branch, which feeds the hand’s thenar muscles (flexor pollicis brevis, abductor pollicis brevis, and opponens pollicis), is immediately released by the median nerve when it emerges from the carpal tunnel and transverses beneath the palmar aponeurosis. The anterior interosseous nerve, which passes outside of the carpal tunnel and supplies the flexor pollicis longus, is the final contribution of the median nerve to the thumb.

The median nerve divides into radial and ulnar divisions at the palmar aponeurosis, and these divisions then split into the common palmar digital branches. The palmar side of the thumb, index finger, middle finger, and radial half of the ring finger are all sensed by these digital branches, which also innervate the first two lumbrical muscles. Additionally, the dorsal surface of the index and middle fingers as well as the lateral portion of the ring finger beyond the proximal interphalangeal joint (i.e., over the nailbeds) receive sensory innervation entirely from the median nerve.

Function

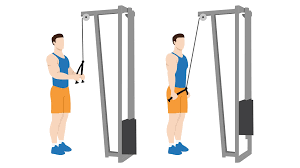

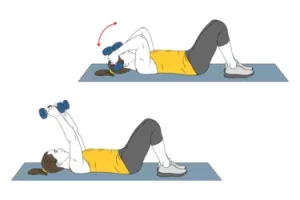

The median nerve stimulates the muscles in your forearm, allowing you to:

- Bend and straighten your wrists, thumbs, and the first three fingers.

- Rotate your forearm and hand, bringing your palm down.

Touch, pain, and temperature sensations are also controlled by the median nerve:

- The bottom (palm) sides of the thumb, index, and middle fingers, as well as a piece of the ring finger.

- middle fingers, as well as a piece of the ring finger.

- Forearm.

- The thumb side of the palm.

- The upper (nail bed) side of the middle and index fingers

Muscle supplied

The anterior compartment of the forearm has four layers of muscles innervated by the median nerve. The first layer, which starts at the medial epicondyle, is composed of three muscles: the pronator teres, flexor radialis longus, and palmaris longus. The flexor digitorum superficialis, whose tendons attach to the middle phalanx of the four fingers, is located in the second layer. As a result, it is a finger flexor at the proximal interphalangeal joint. The median nerve properly innervates the first and second layers.

The flexor pollicis longus, pronator quadratus, and the lateral portion of the flexor digitorum profundus, which innervates the index and ring fingers, are the muscles that make up the third layer. The anterior interosseous nerve, which lacks sensory branches, innervates them.

Sensory innervation: None of the sensory nerves that serve the forearm crosses the wrist (except the palmar branch of the median nerve). The palmar surfaces of the index finger, middle finger, lateral half of the ring finger, and a portion of the thumb make up the hand’s median nerve’s sensory distribution. The ulnar nerve supplies the remaining sensory innervation of the hand, which includes the medial hand, the medial part of the ring finger, and the entire little finger. Through its dorsal branch, the ulnar nerve also supplies feeling to the medial dorsal surface. It is the superficial branch of the radial nerve that completes innervation of the dorsal surface of the hand.

Branches and innervation

The median nerve throws out several branches in the forearm and hand areas. The branches in the forearm area include:

Innervating the equivalent muscles are the muscular branches to the pronator teres, palmaris longus, flexor digitorum superficialis, and flexor carpi radialis.

The radial portion of the flexor digitorum profundus and the flexor pollicis longus are supplied by the anterior interosseus nerve. To nourish the pronator quadratus, this branch travels deep into the interosseous membrane alongside the anterior interosseous artery. It ends by providing articular branches to the carpal, radiocarpal, and distal radioulnar joints.

The hand’s principal branches consist of:

The proximal portion of the palm is supplied by the cutaneous nerve of the palm. Since this branch avoids the carpal tunnel, it is not affected by carpal tunnel syndrome.

The first of the two common palmar digital nerves supply the radial to lumbricals. The second separates between the middle and ring fingers to provide the appropriate digital nerves that give some parts of the hand feeling.

The muscles of the thenar eminence (flexor pollicis brevis, abductor pollicis brevis, and opponens pollicis) are the recurrent branch. Because of its significance for fundamental hand function, it is frequently referred to as the “million-dollar nerve.”

In summary, the flexor muscles of the forearm receive their motor supply from the median nerve, except the flexor carpi ulnaris and the ulnar head of the flexor digitorum profundus, which receives its supply from the ulnar nerve. It also feeds the radial two lumbricals and the thenar muscles.

The following are part of the median nerve’s sensory supply:

the distal dorsal and palmar skin of the neighboring palm and the lateral three-and-a-half digits.

the radial part of the second finger and the skin of the thumb’s palmar and distal dorsal sides.

the distal dorsal and palmar skin of the neighboring sides of the second through fourth fingers.

the central palm’s skin.

Examination

Neuro-Examination

The following are motor indicators of a median nerve lesion:

- Forearm pronation that is weak

- Wrist radial deviation and weak flexion due to tendon atrophy

- incapable of flexing or opposing the thumb

The following are sensory indicators of a median nerve lesion:

The thumb, radial 2 1/2 fingers, and the matching palm are included in the sensory distribution.

When the nerve is intact, the thumb may be pronated and the nails line up at or close to 180 degrees; when the median nerve palsy is present, the thumb cannot pronate and the nail is less than 100 degrees.

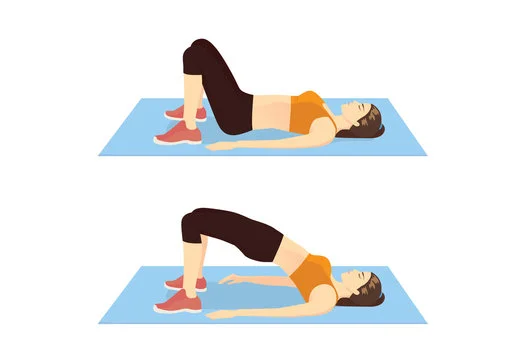

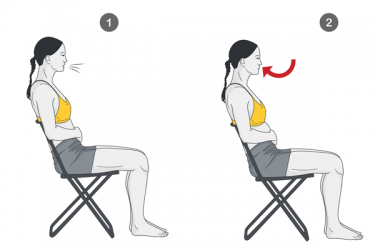

Neurodynamics

The median nerve is strained when the elbow and wrist are extended, two essential parts of the upper limb tension test. The nerve is stretched further when the head and neck are rotated to the other side. Raising the arm above the head typically improves the reaction if the entrapment is in the inter-scalene triangle. The goal is to determine whether the patient’s arm and shoulder discomfort is coming from the median nerve, the C5, C6, and C7 nerve roots.

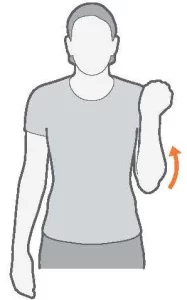

Median Nerve test in the Upper Limb Tension Test 1 (ULTT1)

- Depression of the Shoulder Girdle

- Abduction of the Shoulder Joint

- Supination of the Forearms

- Extension of the Wrist and Fingers

- Laterally Rotated Shoulder Joint Extension of the Elbow

Median Nerve Bias, or Upper Limb Tension Test 2A

- Elbow Extension

- Shoulder Girdle Depression

- Extension of the thumb, fingers, and wrists as well as lateral rotation of the whole arm

Clinical Importance

High Median Neuropathy

Check for atrophy in the thenar eminence during the physical examination. Evaluate the lateral three-and-a-half digits’ mild touch sensitivity. The median nerve proper provides direct innervation to the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, and flexor digitorum superficialis. Pronator teres weakness and severe forearm flexion weakness at the elbow (flexor carpi radialis and flexor digitorum superficialis) are the results of injury to these muscles. It is possible to measure the patient’s finger flexion by holding their hand. Because the tendons of the flexor digitorum superficialis attach to the sides of the fingers, a high median neuropathy will result in weakness at the proximal interphalangeal joint.

To assess the anterior interosseous branch, ask the patient to use their thumb and index finger to form the “okay” sign. An anterior interosseous nerve palsy is indicated by a pinch rather than a circle. To evaluate the distal portions of the nerve, it is also possible to measure the thumb’s opposition and abduction by asking the patient to lay their hand flat on the bed and then ask them to elevate their thumb off the bed. This is one of the symptoms of neuropathy with a high median.

Ask the patient to create a fist if there is a suspicion of median nerve pathology above the elbow. The flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) function will be impacted by a lesion at this level, which will impede the ability to flex all four fingers at the proximal interphalangeal joint. The index and middle digits’ distal interphalangeal joint will become less flexible if the anterior interosseus nerve is lost. The middle and index fingers will stay out while trying to form a fist. This is sometimes called the “preacher’s hand” or the “hand of benediction.” A “pointer finger”—pointing with the index finger—is a better way to describe the observed phenomenon since, in clinical practice, anatomic variations of the ulnar nerve usually permit bending of the middle finger at the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint. A high median neuropathy includes this.

High median neuropathy can arise from a supracondylar humeral fracture that damages the whole nerve.

The simultaneous incapacity to flex the thumb’s distal phalanx and index finger, poor middle finger flexion, and impaired thumb opposition can result in a single-palmar crease appearance when a median nerve lesion occurs at the elbow or forearm. A high median neuropathy includes this.

Low Median Neuropathy

Carpal tunnel syndrome and median recurrent neuropathy are examples of low median neuropathies. The flexor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, and abductor pollicis brevis are all denervated when the recurrent branch of the median nerve is damaged. Near the center of the thenar muscle mass lies the rather superficial location of the median nerve’s recurrent branch. When cleaning dishes, dishwashers might cause a minor cut on a knife or shard of glass, which can harm the recurrent branch of the median nerve. When examining sensory function across the hand, an unwary ER doctor would observe no loss of sensation. He could next seal the incision with a stitch or a piece of surgical tape. Due to significant thenar muscle atrophy and loss of thumb motor function, the patient will return in a few weeks. Because the doctor was unaware that the recurrent branch of the median nerve has no sensory function, this constitutes medical misconduct. The opposition test requires the patient to touch the thumb and little finger pads together during the physical examination of such a patient. The patient would not have been able to resist the thumb if he had been asked to. it would instantly have been clear that he had experienced a median recurrent neuropathy.

Thumb muscle mass is lost when the thumb’s innervation is compromised. Even though most apes have opposable thumbs, this is commonly referred to as the “ape hand.”

The median nerve is located medial to the brachial artery at the elbow. Because it is readily available, the radial artery is frequently used when arterial blood gas levels need to be sampled by arterial puncture. However, because the puncture may result in thrombosis of the radial artery, the Allen test should be performed to ascertain whether the anastomosis between the radial artery and ulnar artery is enough for the ulna artery to deliver blood to the thumb and index finger. The brachial artery may be sampled if the Allen test indicates insufficient radial artery perfusion. To prevent harm to the median nerve, the anatomical location of the radial artery to the nerve becomes crucial. If at all feasible, one initially uses a pulse to get a good localization of the radial artery. If sonography is available, it should be used since it can produce better results. To protect the median nerve, it is crucial to avoid puncturing the region medial to the brachial artery.

Injection An intramuscular injection administered close to or directly into a nerve can result in axonal and myelin degradation, which causes nerve palsy, an iatrogenic disease. The substance can enter the endoneurium, which causes edema around a single nerve fiber and, eventually, damages or even kills the nerve. The patient will experience excruciating pain, and motor function will usually be more negatively impacted than sensory function. Penicillin, chlorpromazine, meperidine, dimenhydrinate, tetanus toxoid, procaine, and hydrocortisone are considered to be the most poisonous substances.

Wrist Lesions

Particularly in cases of wrist fractures, traumatic damage to the median nerve at the wrist level is far more common. Simple compression by fracture stumps, nerve contusions, and infrequent nerve tears are all examples of nerve injury. Furthermore, the median nerve on the wrist is particularly vulnerable to severing wounds and puncturing items, which may result in its whole or partial section. Painful amputation neuromas can arise from traumatic or unintentional iatrogenic injury during wrist surgery, as well as from a lesion of the palmar sensory branch of the median nerve.

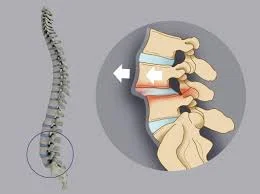

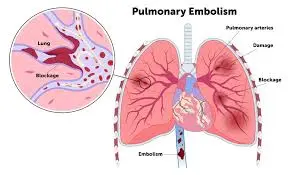

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

The median nerve and nine flexor tendons are located inside the carpal tunnel, which is anatomically created by the flexor retinaculum superiorly and the carpal bones inferiorly. In addition to radiating into the forearm, symptoms may be localized to the wrist or the entire hand. Carpal tunnel syndrome is characterized by paresthesias, numbness in the radial three-and-a-half fingers, and thenar weakening. Additional symptoms include a burning sensation throughout the median nerve’s distribution. The symptoms may resemble those of a C6 or C7 nerve root damage.

Carpal tunnel syndrome is an isolated damage to the distal median nerve, which helps differentiate it from a nerve root injury. Patients are usually awakened from their sleep by symptoms that are worse at night. Neither wrist extension weakness nor triceps are present. The Tinel and Phalen tests can also be used to differentiate carpal tunnel syndrome. Tenderness or swelling in the cubital fossa may indicate damage to the median nerve as well as a loss of wrist flexion and pronation muscle strength. On examination, thenar atrophy may indicate long-term damage to the median nerve. Carpal tunnel syndrome is suggested by a positive Tinel sign. Carpal tunnel syndrome is also indicated by a positive Phalen maneuver. These specialized tests are explained below.

When a patient is awakened from sleep with carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms and has to flick their hands to alleviate the discomfort, this is known as a flick sign. For carpal tunnel syndrome, the test has a 93% sensitivity and a 96% specificity. The Tinel sign or the Phalen maneuver is just as effective as the hand elevation test. To simulate the symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome, hand elevation tests can be performed by having the patient raise their hand over their head for one minute.

The Phalen maneuver, Tinel sign, and median nerve compression test are additional specialized tests to be taken into account during physical examinations for carpal tunnel syndrome. The Phalen maneuver involves the patient fully extending their elbows while flexing their wrist 90 degrees. A positive test result is when carpal tunnel symptoms are recreated in less than 60 seconds. When quick, repetitive tapping across the volar surface of a patient’s wrist in the carpal tunnel region replicates carpal tunnel symptoms, the Tinel test is considered successful. Additionally, if direct pressure on the transverse carpal ligament replicates carpal tunnel symptoms within 30 seconds, the median nerve compression test is positive.

Carpal tunnel syndrome has three severity levels: mild, moderate, and severe.

Numbness and tingling in the median nerve distribution without motor or sensory impairments are symptoms of mild carpal tunnel syndrome. There is no disturbance in the patient’s sleep, and everyday life activities remain unchanged.

Sleep disturbances, sensory loss in the median nerve distribution, minor carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms, and possible hand function impairments are all part of moderate carpal tunnel syndrome.

Severe carpal tunnel syndrome includes symptoms of mild and intermediate carpal tunnel syndrome, alterations in daily living activities, and weakening of the median nerve distribution.

Pronator Syndrome

When the median nerve is compressed by the pronator teres, pronator syndrome, also known as pronator teres syndrome, results. This ailment might resemble carpal tunnel syndrome quite a bit. Patients with pronator syndrome frequently complain of forearm pain as they move. Pronator syndrome symptoms, such as tingling and numbness in the thumb and first two fingers, can sometimes be mistaken for an extended elbow and recurrent pronation. The feeling is generally intact to the forearm and fingers pronator syndrome; nevertheless, there is often the loss of sensation over the thenar eminence. Another method of differentiating pronator syndrome from carpal tunnel syndrome is by this presentation. In cases with pronator syndrome, the Tinel sign and the Phalen maneuver are also frequently negative. Professional cyclists are often affected with pronator teres syndrome, a condition in which the median nerve becomes stuck as it travels through the pronator teres. Although the lateral palm is the most frequently affected area, the thenar eminence is also affected, as was previously indicated.

Elbow Lesions

When an elbow fracture or dislocation occurs, the median nerve may be affected directly by the fracture stumps, which in extreme cases may rip the median nerve, or indirectly by the acute compression or stretching of the nerve due to perineural hemorrhages. Once more, during the reparative fibrous processes, the nerve may be involved and may be incorporated and constrained. If the dislocation is lessened or an attempt is made to realign the fracture pieces, the median nerve may get trapped or imprisoned between the articular heads after the dislocation or between the fracture stumps themselves. In addition to the fibrous laceration at the elbow, compressions of the median nerve may occur at the level of the round pronator muscle. Muscle weakness and severe neuropathic symptoms are possible outcomes of the former disease. Additionally, routine elbow surgeries such as elbow arthroscopy, stiff elbow correction, prosthetics, or fractures (iatrogenic damages) might result in a median nerve lesion.

Arm, Axillary, or Upper Lesions

Acute traumatic injury from a deep incision is more common than traumatic injury of the arm, such as humerus fractures, which can seldom result in paralysis of the median nerve. Nerve lesions at the axilla or higher may be caused by stab wounds, gunshot wounds, high-energy traumas like auto accidents, or more complicated brachial plexus injuries. When this kind of damage occurs, the innervated muscle of the median nerve becomes paralyzed, and sensory impairment occurs.

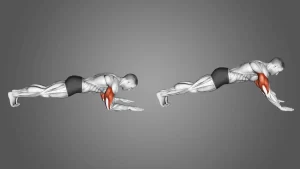

Hand of Benediction

When an elbow injury occurs, especially a supracondylar fracture, the median nerve is especially vulnerable. The flexor digitorum profundus muscle’s radial head innervation may be compromised by such injury. The inability to bend the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints of the second and third fingers results from the disruption of innervation in the two lateral lumbricals. When the patient tries to flex their fingers, the hand takes on a common position known as the “hand of benediction” (which also includes injury to the ulnar nerve), making it hard to create a fist.

Simian/ape hand deformity

Damage to the recurrent motor branch of the median nerve results in the denervation of the thenar eminence muscles. This comprises the two radial lumbricals, opponens pollicis, flexor pollicis brevis, and abductor pollicis brevis. As a result, the person can no longer oppose the thumb, that is, bring the thumb’s tip to the tips of the other fingers. The unopposable thumb gives the hand the look of an ape’s hand (Ape Hand Deformity). The radial head of the flexor digitorum profundus is still functioning, which sets this apart from the hand of benediction.

Anterior Interosseous Syndrome

Although patients may report dull forearm discomfort, Anterior Interosseous Syndrome is a pure motor neuropathy because the anterior interosseous nerve lacks sensory fibers.

Patients usually are unable to form the “O K Sign” because of poor bending of the thumb’s interphalangeal joint and the index finger’s distal interphalangeal joint.

A patient with the anterior interosseous syndrome will also be unable to squeeze a piece of paper between their thumb and index finger, as opposed to clamping it between their extended thumb and index fingers, like a tong rather than a clamp. This is another sensitive test.

Up to 25% of people have the Martin-Gruber Anastomosis, which can confuse anterior interosseous syndrome. In these cases, the anterior interosseous nerve branches off to the ulnar nerve, resulting in abnormal motor innervation patterns of the hand and forearm and obscuring the usual clinical symptoms.

Surgical Importance

The anterior interosseous branch of the median nerve is vulnerable above the site of the ulna fracture in a Monteggia Fracture (radial head dislocation with a concomitant proximal ulna fracture). This can cause compression or stretching, which can lead to traction or compression neuropathy. Entrapment, straining, scarring, displacement, or direct trauma can also result in posterior interosseous nerve palsy. The tension on the nerve will be lessened concurrently by open reduction and internal fixation of the ulna fracture, which has been linked to the nerve’s restoration to normal function.

A frequent condition affecting the median nerve as it travels beneath the wrist’s small flexor retinaculum (transverse carpal ligament) is carpal tunnel syndrome. When the tendons are overused, the median nerve may become inflamed and compressed as it travels through the hand, resulting in severe pain and weakness. The afflicted hand’s first three and a half fingers will be numb or painful, and this usually gets worse at night. The thenar eminence often exhibits weakness if it is significant. Pregnancy, weight increase, repetitive occupations (like typing, computer work, or writing), and excessive hand usage (like mechanics, carpenters, and cashiers) are lifestyle risk factors for the development of carpal tunnel syndrome. Additional risk factors for carpal tunnel syndrome include diabetes, hypothyroidism, arthritis, and prior trauma. Bracing, splinting, occupational therapy, and over-the-counter (OTC) anti-inflammatory drugs are examples of conservative treatment methods. Surgery to relieve the carpal tunnel may be necessary if these don’t alleviate the discomfort.

However, because the pronator teres muscle’s bellies squeeze the nerve, the discomfort is restricted to the anterior proximal forearm. Patients will report experiencing paraesthesia in the median nerve’s distribution. Nevertheless, the palm will also feel numb. Pronator syndrome has risk factors with repeated actions that cause carpal tunnel syndrome. Nevertheless, there hasn’t been much research to back up the idea that surgical decompression can alleviate symptoms. Conservative treatment, which includes rest, ice, immobilization, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and physical therapy, will help the majority of patients (between 50% and 70%) recover.

FAQs

What is the median nerve for?

What is the median nerve? Your forearm, wrist, hand, and fingers may all be moved with the aid of the median nerve. It also provides sensation to the forearm and certain parts of the hand. (The lower portion of your arm that runs from the elbow to the hand is called your forearm.)

How to test the median nerve?

Apply pressure with your thumbs over the median nerve in the carpal tunnel, which is situated immediately distal to the wrist crease, to perform the carpal compression test. If the patient experiences tingling and numbness within 30 seconds, the test is considered successful.)

What happens if the median nerve is cut?

When the median nerve is injured, the lateral three-and-a-half fingers on the palmar and dorsal sides of the hand may lose their general feelings. When a median nerve lesion occurs, the affected skin may become dry and heated, resulting in sensory loss.

Which surgery is better for carpal tunnel?

Although endoscopic carpal tunnel release is usually linked with reduced discomfort in the initial weeks of recuperation, both open and endoscopic carpal tunnel release operations have great long-term results. People can frequently go back to work early thanks to it.

What are the symptoms of median nerve damage?

alterations in sensation, including tingling, numbness, burning, and diminished sensation in the thumb, index, middle, and a portion of the ring fingers. a hand weakness that makes it difficult to hold objects, button shirts, or drop things.

Referances

- Park, S. (2024). Median nerve anatomy and entrapment syndromes. The Nerve, 10(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.21129/nerve.2024.00549

- Median nerve. (2023, November 2). Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/the-median-nerve

- Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. (2025, February 7). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4005-carpal-tunnel-syndromeLog in