Medial Collateral Ligament Injury

Definition:

A medial collateral ligament (MCL) injury occurs when the ligament on the inside of the knee is over-stretched, partially torn, or torn completely. It is mostly caused by a valgus force on the knee and is among the most frequent knee injuries.

What is a Medial Collateral Ligament Injury?

Your MCL and the other ligaments in your knee help to stabilize it. Your knee’s sideways movement is controlled by your lateral collateral ligament and MCL.

Damage to the medial collateral ligament, a significant ligament on the inside of your knee, is known as an MCL tear. A partial tear occurs when some of the ligament’s fibers are injured, while a complete tear occurs when the ligament is injured in two. A ligament is a strong band of tissue that maintains organs in place or joins two bones.

An MCL Injury occurs when the knee ligament is strained but not broken. Based on their severity, sprains are graded differently.

A common knee ligament injury that frequently occurs during activities like rugby and skiing is an MCL injury. Meniscus or cruciate ligament injuries frequently occur concurrently with MCL injuries.

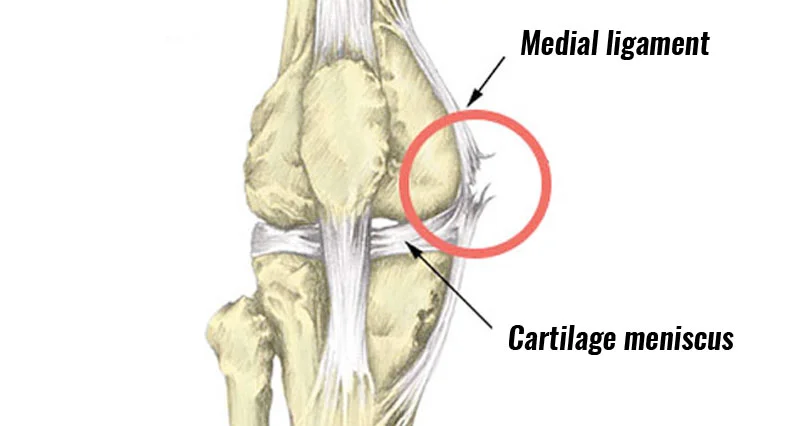

Clinically Relevant Anatomy:

A large ligament on the medial side of the knee is called the medial collateral ligament. Click here to view additional therapeutically important knee anatomy. One of the four ligaments that are essential to preserving the knee joint’s mechanical stability is the medial collateral ligament (MCL). From the medial aspect of the extensor mechanism to the posterior aspect of the knee, the ligamentous sleeve covers the whole medial side of the knee.

In addition to controlling excessive motion by restricting joint mobility, a ligament, which is composed of many collagen fibers and small elastic fibers, is a source of proprioception. Its purpose is to stop the medial part of the knee from enlarging under stress by fending against forces from the knee’s exterior. Ligaments, muscles, and joint capsules all include proprioceptors. These proprioceptors track our movements, the effort we put in while lifting objects, and the location of our limbs in space.

Epidemiology:

MCL injuries typically happen when the foot is in contact with the ground and immobile following an impact to the outside of the knee, lower thigh, or upper leg. The impact will put tension on the MCL on the inside of the knee, and flexion, valgus, and external rotation will cause the fibers to tear.

The athlete may experience pain very far away, as well as a popping or tearing sound. The deep portion of the ligament typically sustains injury first, which can result in anterior cruciate ligament or medial meniscal damage.

Causes of medial collateral ligament (MCL) injury:

Usually, pushing your knee inward toward your other knee results in an MCL injury. A direct impact to the outside of your leg, which frequently occurs during sports like rugby, might cause this. Another way to hurt your MCL is to twist your knee, like you would when skiing. and from putting a lot of strain on your knee, like when swimming the breaststroke. Falling can potentially cause injury to your MCL. When the ligament is overstretched and the valgus force is too large for it to withstand, the MCL is injured.

Symptoms of medial collateral ligament injury:

You will most likely experience some pain on the inside of your knee if you have injured your MCL. Additionally, this area could feel sensitive to the touch.

Your knee may feel unsteady and as though it might give way, depending on the extent of your damage. You should still be able to walk on it if your injury isn’t too bad.

With an MCL injury, you might have some swelling, but this is not always the case. Additionally, you can get some bruises; these may not show up for one to three days following your incident.

- hearing a popping noise when the injury occurred.

- You are having knee pain.

- experiencing knee swelling and stiffness.

- feeling that if you put weight on your knee, it will “give out.”

- When you utilize it, you may feel your knee joint lock or catch.

Clinical Presentation:

The MCL damage can be classified as I, II, or III, just like all other ligament injuries; the grade is determined by the extent of the rupture. Less than 10% of the collagen fibers are injured in a grade I tear, which is characterized by considerable pain but no instability. When force is applied to the outside of a slightly bent knee, the majority of patients experience pain; however, no other symptoms are present.

Because grade II tears have different symptoms, they are further divided into grades II- (which are closer to grade I) and II+ (which are closer to grade III). Both of these grades are considered to have tenderness but no instability. Compared to grade I injuries, the pain and edema are more severe. Patients report pain and severe tenderness on the inside of the knee when the knee is stressed (as with grade I), and the joint exhibits moderate laxity.

This clearly indicates that a grade III injury is an MCL rupture that causes instability. Over the MCL, patients experience severe pain and swelling. They frequently struggle to bend their knees. As previously said, a grade III rupture causes instability because it causes joint laxity when the knee is pressured, as mentioned above. An additional scale is used to gauge the degree of instability in grade III MCL injuries. More details may be found here. These are characterized by the degree of joint separation in the 30° valgus test.

In contrast to a grade III tear, which has a soft endpoint with valgus stress testing, grade I and II injuries have clearly defined endpoints. Less than 10% of the collagen strands are torn in a grade I tear. Because the symptoms of grade II tears differ, they are further divided into grades II-, which are closer to grade I, and II+, which are closer to grade III. This clearly indicates that a grade III injury is an MCL rupture.

Patients report pain, mild joint laxity, and severe internal knee tenderness when the knee is under stress (as with grade I). Patients have severe pain and swelling over the MCL when they suffer a grade III injury. They frequently struggle to bend their knees. Instability is another typical observation of a grade III tear. Joint laxity occurs when the knee is stressed, as previously mentioned.

Severity of MCL Injury:

The extent to which the knee ligament is stretched or torn determines the severity and symptoms of a sprain. When your ligament injury occurs, you might hear a snapping or tearing sound.

The knee ligament stretches somewhat but does not tear in a modest Grade I MCL sprain. Even though the knee joint might not be exceedingly painful or swollen, a minor ligament sprain might raise the chance of recurrent injuries.

A mild Grade II MCL sprain causes a partial tear in the knee ligament. The knee joint is typically uncomfortable and difficult to use, and knee swelling and bruises are prevalent. You can complain of knee instability or a yielding sensation.

The ligament totally tears in a severe Grade III MCL sprain, resulting in edema and occasionally subcutaneous hemorrhage. The joint becomes unstable as a result, making it challenging to support weight. You can feel as though your knee is giving out. Since all of the pain fibers are ruptured at the time of injury, a grade 3 tear frequently results in either no pain at all or severe agony that goes away fast. The meniscus and/or ACL are among the other structures that could sustain damage from these more severe injuries.

Differential Diagnosis:

- Medial meniscal tear/injury

- Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear

- Tibial plateau fracture

- Femur injury or fracture

- Patellar subluxation/dislocation

- Medial knee contusion

- Pediatric distal femoral fracture

- Damage to the posteromedial corner structures.

A proper diagnosis can be ensured with the aid of a physical examination. Because a medial meniscal tear produces joint soreness similar to that of an MCL sprain, they can be confused. A medial meniscal tear can be distinguished from a grade II or III MCL sprain using a valgus laxity assessment. The medial meniscus is torn if there is an opening on the joint line. It is more challenging to distinguish a grade I MCL from a medial meniscal injury. An MRI or weeks of patient observation can be used to make the distinction. Tenderness normally goes away after an MCL sprain, although it can linger after a meniscal injury.

A medial knee contusion may be the cause of the soreness if there is no excessive valgus laxity. Patellar dislocation or subluxation is more likely to be the reason if the pain is located close to the adductor tubercle or medial retinaculum next to the patella. The patellar apprehension test can be used to distinguish between patellar instability and an MCL sprain. If the test is positive, patellar instability is present. A mild stress-testing radiograph can identify whether a youngster has a distal femoral fracture rather than an MCL sprain.

Diagnosis:

To determine the location of the pain, the patient’s anamnesis is crucial. The therapist must first identify the area of pain and then feel for any sensitivity or swelling of the soft tissues. He must palpate the knee joint for that. The medial side of the knee is where the pain is typically located. There will also be soft-tissue edema. Three grades of MCL tears exist, as previously mentioned. The range of the joint space opening during stress tests of the patient’s knee joint or the level of pain are what determine the grade.

- MCL valgus stress test

- Swain test

- Anteromedial drawer test

- MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, creates fine-grained pictures of your bones and organs using radio waves, a big magnet, and a computer. The preferred imaging test for MCL tears is an MRI. It can assist your healthcare professional in determining whether you have any other knee soft tissue damage.

- Ultrasound: Ultrasound captures images of your internal organs using sound waves. Your doctor can use an ultrasound to determine the extent of your MCL tear and whether you have any further knee issues.

- X-ray: To make sure you don’t have any broken bones or other problems in your knee, your doctor might take an X-ray of it.

Physical Examination:

To determine if the lesion is limited to the MCL or if other structures are harmed, a clinical evaluation is crucial. First of all, the patient’s account of the injury can reveal a great deal. Second, to compare the two legs, the contralateral knee should be inspected. When examining the knee, it’s critical to identify and pinpoint any edema. On the medial side of the knee, a solitary swelling is typically observed.

To determine the site of maximal tenderness (femoral versus tibial sides), it is crucial to palpate the MCL along the medial aspect of the knee. From this vantage point, we are rather certain that the MCL is damaged. Thirdly, it’s critical to pay attention to the injury process to determine which structures are harmed.

It’s also crucial to let people know that the optimum time to have their knees examined is just after the accident, before any muscle spasms can happen. Regretfully, this chance only arises when medical professionals are present when the damage occurs. Giving patients with severe muscle spasms 24 hours of immobilization to relax is usually enough, and anesthesia is rarely required for testing.

The two-part valgus stress test can be performed to assess the medial collateral ligament itself. The knee is first subjected to a valgus stress when fully extended. Second, the knee is flexed by 30 degrees while the same test is conducted. Assessing the medial joint space widening and feeling for a solid endpoint requires probing the MCL with the knee at both 0° and 30° of flexion. To prevent the examiner from overestimating the degree of laxity caused by the knee shifting from internal to external rotation, the foot must be held in external rotation during the test. Any asymmetry is regarded as a positive test result. With the knee at 0°, laxity to valgus stress suggests the potential for a compounded injury. An injury to the cruciates or posteromedial capsular structures is likely to cause this. You can go to the Knee examination for further details on this test and how to interpret it.

The Swain test is a second test that can be used to assess the medial collateral ligament. This test looks at the knee’s rotatory instability and chronic damage. The exam involves externally rotating the tibia and flexing the knee to 90 degrees. While the collateral ligaments are tightened, the cruciates relax in this knee posture. An injury to the MCL complex is likely to occur when pain is experienced on the medial side of the knee.

The anteromedial drawer test is another test that can be used to determine whether the damage primarily affects the superficial and deep MCLs and how much rotational stability is present. Another crucial tool for assessing a medial collateral ligament injury is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). As of right now, it is the only tool capable of visualizing both functional and morphological joint damage.

Treatment of Medial Collateral Ligament Injury:

Medical Treatment:

- Applying the RICE (rest, ice, compression, elevation) technique entails elevating your knee while you’re sleeping, applying an elastic bandage to compress it, resting your knee, and icing it. The RICE technique aids in lowering swelling and pain.

- Taking analgesics: To assist in lessening knee pain and swelling, your doctor could advise using painkillers, often known as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or NSAIDs.

- Wearing a knee brace: To allow your MCL to recover, your doctor may advise you to wear a knee brace that stops your knee from moving side to side.

- Using crutches: In order to reduce the amount of weight you place on your injured knee, your doctor may advise you to walk using crutches.

Every ligament damage has the same initial three grades. The ligament is sprained in grade I, partially torn in grade II, and completely torn in grade III. It happens when more than just the medial collateral ligament (MCL) is injured, and surgery might be necessary. Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries, bone bruising, lateral collateral ligament injuries (LCL), lateral and medial meniscus tears, and posterior cruciate ligament injuries (PCL) are frequently observed in conjunction with medial collateral ligament injuries. High-grade MCL tear are most frequently linked to ACL disturbances.

The outcomes of non-operative treatment are less clear when the injury is grade III. The position of the injuries (more to the tibial or femoral side of the ligament), whether they are isolated to the MCL or coupled with other ligamentous injuries, and whether posterior structures are involved will all affect the course of treatment. The precise location of the injury can be found via MRI imaging, which can aid in therapeutic decision-making. Therefore, injuries involving numerous ligaments (grade 4) may necessitate immediate reconstruction or augmentation. There are various methods for augmentation. An augmentation involves using a tendon from a muscle, such as the hamstrings, to “replace” the ACL.

Chronic valgus, rotational instability, and functional limitations may result from a failure to identify combination injuries or insufficient healing of the medial side of the knee. particularly when the posterior oblique ligament complex (POL) is involved. Finding the involvement of the posterior oblique ligament and capsule required further attention. Although non-operative treatment for grade III MCL injuries has produced positive results for certain researchers, the outcomes are not as reliable as those for grade I and II tears.

Surgery is not necessary for the majority of isolated grade III injuries, which are based at the femoral site. Examining the posterior oblique ligament (POL) and posterior capsule for injury is a crucial step in determining whether surgery is required. When there is damage to the pes anserinus tendons, surgery should also be considered. An operation is usually the best course of action for injuries that affect the entire superficial layer, such as when the tibia’s superficial and deep MCLs are completely injured. Moreover, Grade III injuries that are unstable in 0-degree extension are included in the group for which surgery is advised. It is also important to remember that isolated symptomatic chronic medial-sided knee injuries require surgical reconstruction.

Surgical Treatment:

The majority of MCL injuries heal satisfactorily with conservative treatment; however, if there is severe ligament damage, such as in Grade III, surgery might be considered. If there is severe combined damage to the meniscus and/or ACL, surgery can also be necessary. A knee specialist will determine whether surgery is necessary in these situations.

Infection, chronic instability, pain, stiffness, and difficulty resuming your prior level of activity are among the risks associated with surgery. The good news is that after surgery, over 90% of patients experience no problems.

Post-Surgical Rehabilitation:

One of the most crucial parts of knee surgery is post-operative knee rehabilitation. Under the direction and supervision of a skilled sports physical therapist, the best and fastest results are achieved.

Strength, power, endurance, and full knee mobility are the main goals of your physical therapy rehabilitation after knee surgery. Additionally, you will need retraining in balance, proprioception, and agility tailored to your unique customized or athletic needs.

Your sports physical therapist is a specialist in this area, as was previously indicated. For the greatest guidance in your situation, we advise you to get in touch with them.

Your return to sports will be guided by your physical therapist. It varies greatly and is dependent on the demands of your sport as well as your particular knee ligament problem.

Physical Therapy Treatment:

Surgery is rarely necessary to treat a medial collateral ligament injury. The medial collateral ligament, which is extracapsular, seems to have a pretty strong capacity for healing. The MCL tear may be repaired or rebuilt surgically if there is still instability following nonoperative treatment or if there is ongoing instability following ACL and/or PCL reconstruction.

Bracing or immobilization are effective non-operative treatments for the most isolated MCL injuries. Patients can resume their prior level of activity with the help of rehabilitation and a few easy therapy methods. The majority of treatment plans emphasize early range of motion, edema reduction, safe weight bearing, and the development of strengthening and stability activities. Restoring an athlete or patient to full activity is the main objective.

Grade 1:

Isolated grade I injuries are primarily treated non-operatively. Use as much elevation, compression, and ice as you can throughout the first 48 hours. Crutches are typically used to alleviate pain and temporarily immobilize patients with partial MCL tears. Within a few days of the pain and swelling going down, gradual resistive workouts that are isometric, isotonic, and eventually isokinetic are started. Weight-bearing is advised, with the rate determined by the degree of pain.

Grade II / III:

Treating a grade II or III damage requires protecting the ligament’s ends and allowing them to recover without constant disruption. To ensure that the injury can heal properly, it is best to wait three to four weeks following the accident before introducing considerable loads to the healing structures. Whether a grade III injury occurs alone or in conjunction with other ligamentous injuries determines how it should be treated.

According to the recommendations for an isolated medial knee injury, the standard procedure for a grade III medial knee injury that coexists with another injury, such as an ACL rupture, is to treat the medial knee injury first to allow for healing. ACL repair can start as soon as there is solid clinical and/or objective proof that the medial knee damage has healed, which is typically 5 to 7 weeks following the injury.

Rehabilitation:

Four stages can be distinguished in the rehabilitation process for a non-operative treatment:

The first phase lasts for one to two weeks. In phase one, the knee’s swelling is managed by applying ice for 15 minutes every two hours for the first two days. The frequency can be lowered to three times each day for the remainder of the week. Apply ice as required by symptoms and as tolerated. The patient must initially utilize crutches.

Early weight bearing is recommended because patients can gradually lessen their reliance on crutches as their weight bearing increases. After that, move on to one crutch and only allow the patient to cease using them when they can walk normally. Maintaining the capacity to bend and straighten the knee from 0° to 90° knee flexion is another goal of this phase.

It’s crucial to prioritize complete extension and advanced flexion as tolerated to reach the knee’s range of motion. It is advised to perform pain-free stretches for the calf, groin, quadriceps, and hamstrings. The therapeutic activities come last. When pain permits, the patient may start with static strengthening exercises.

Quadriceps sets, straight leg lifts, range-of-motion exercises, sitting hip flexion, sidelying hip abduction, standing hip extension, and hamstring curls are a few examples of what they include. Patients are recommended to ride a stationary bike to increase their knee range of motion as soon as they can handle it. This would guarantee a quicker recovery. As tolerated, the amount of time and effort spent on the stationary bike is increased. Each patient is unique, and these are not the required standard workouts. Exercises for the upper extremities that do not impact the damaged knee have no restrictions. In addition to ensuring that the MCL is adequately covered (by wearing a stabilized knee brace), the patient must refrain from any uncomfortable activities and utilize crutches if required.

Phase two starts in the third week. The range of motion goals are identical to those of phase one. Increase your biking time to 20 minutes. As the patient is able, increase the resistance as well. Cycling will help you recover, regain your strength, and keep up your aerobic conditioning. Other exercises that the physical therapist can prescribe are step-ups, leg presses (double-leg), and hamstring curls. As a precaution, the patient gets the opportunity to see a doctor every three weeks to confirm that the ligament has healed.

Week five marks the beginning of phase three. This phase’s main objective is to fully bear weight on the damaged knee. When walking with full weight bearing is possible and there is no variation in gait, stop using the brace. The range of motion must be completely reached and symmetrical with the knee that is not affected. As in phase two, the therapeutic exercises are the same. They might help advancement.

To get rid of swelling, we keep using compression and cold therapy. You can start with proprioceptive and balancing exercises at this phase. The patient can utilize a stepper or, if possible, start swimming to maintain aerobic fitness. The patient has the opportunity to see a doctor every five to six weeks as a precaution. You may be permitted to do stress radiography as a precaution when necessary.

Phase four can start six weeks following the knee injury. Stop wearing the brace when walking. For at least three months during the competitive season, athletes are permitted to wear the brace. The use of cold treatment is still necessary. The therapeutic exercises’ primary focus is on everyday or sport-specific motions. It is necessary to raise the intensity of the strengthening exercises and go from double-leg to single-leg workouts. The patient may resume running at a comfortable pace, but be careful that they don’t abruptly alter course. Once strength and full range of motion are restored and the patient passes a sport functional exam, it is best to resume competition as a precaution.

Prevention:

As is often the case, adequate warm-up aids in preventing medial collateral ligament injuries. Programs for neuromuscular warming appear to be particularly effective in lowering a number of knee-related condition. Lateral trunk displacement and excessive knee valgus are prevented by programs that incorporate workouts that focus on balance, landing methods, leg and core muscles, and optimal joint alignment.

These are two risk factors for this kind of damage, as was previously indicated. The warm-up may involve exercises like single-leg landing and side-cutting. These movements carry a considerable danger. The knee will be able to respond to these motions properly if they are managed throughout the warm-up.

Prognosis:

If properly managed, MCL tears typically heal well. MCL tear complications are uncommon. After their injury has healed, the majority of athletes who suffer an MCL tear are able to resume their sport.

The severity of an MCL tear determines how long it takes to heal completely. It normally takes one to three weeks for a grade 1 (mild) MCL tear to heal. With therapy, a grade 2 (moderate) MCL injury usually heals in four to six weeks. Treatment for a grade 3 (severe) MCL injury may take six weeks or longer. It can take longer if you have surgery to repair your MCL injury.

The best defense against a knee ligament sprain is a program of proprioceptive, agility, and knee strengthening exercises. You should talk to your surgeon or physical therapist about returning to high-risk activities like sports too soon.

Conclusion:

An MCL tear will only briefly keep you from participating in the sports and activities you enjoy, despite the fact that it can be distressing to be unable to play your sport. Your ability to recover from an MCL tear depends on your commitment to stick to the treatment plan prescribed by your healthcare team, which will probably involve rest, crutches, and physical therapy. Your MCL will mend most effectively if you stick to your treatment plan.

FAQs

What signs and symptoms indicate damage to the medial collateral ligament?

Pain directly over the ligament on the inside of your knee is the most noticeable symptom of an MCL tear. A “popping” sound and sensation in your knee may also occur at the site of damage. Other common symptoms include swelling, knee instability, bruises, and the inability to bear your own weight.

How may a damage to the medial collateral ligament be repaired?

With rest, ice, and painkillers, most MCL injuries can be treated at home. Crutches and a knee brace that protects yet allows for some range of motion may be recommended by your doctor.

How is MCL treated at home?

With rest, ice, and anti-inflammatory medication, the majority of MCL injuries may be managed at home. Your physician could advise you to use crutches and wear a brace that protects your knee while allowing for some range of motion. For a few weeks, you might need to cut back on your activities.

Can an MCL injury be healed by cycling?

Patients with acute medial knee ligament tears are put in braces and started on an early rehabilitation program that focuses on knee range of motion, edema reduction, and quadriceps reactivation. Regular usage of a stationary bike is the primary rehabilitation exercise for MCL tears.

With MCL, how do you sleep?

There are a few things you can take to deal with MCL sprain pain at night: Elevate your knee: Using pillows or cushions to support your injured leg while you sleep will help reduce inflammation.

Which is better for MCL, heat or ice?

Ice or Heat for Knee Pain,

You should apply ice to your knee for at least 72 hours until the swelling subsides. After then, movement can be restored with the use of heat. The application of heat can assist relieve stiffness and tightness in your joints.

Does walking aid in the rehabilitation from MCL?

Walking without the right support, however, can worsen and slow the healing process in more serious sprains that involve partial or whole tear. It’s critical to keep in mind that exercise is necessary for rehabilitation and that inactivity might hinder the healing process from an MCL sprain.

How can MCL mend more quickly?

Depending on the symptoms, grade 1 MCL sprains require a brief period of rest (48–72 hours of walking only) and then one to three weeks of exercise rehabilitation.

Is MCL self-healing?

Yes, with conservative measures like rest, ice, and physical therapy, the majority of MCL (medial collateral ligament) injuries, particularly partial tears, can heal on their own. However, complete tears or those with additional injuries may need surgery.

When I have an MCL injury, which exercises should I avoid?

keep away of exercises that produce crunching, clicking, or kneecap pain, such as stair-stepper machines, deep knee bends, and squats. With your back to a table, use it for support and balance.

How can an MCL injury be tested for?

During an examination, you will feel for any stiffness or soreness around the inside of your knee and press on the outside of your knee while your leg is straight and bent to test the integrity of your MCL.

With an MCL tear, is it still possible to walk?

Even though it may hurt, you should still be able to walk at the time of the injury if you have a grade 1 (mild) MCL rupture. Walking may be challenging at the time of the injury if you have a grade 2 (moderate) MCL tear since your knee won’t be as stable as it usually is.

What is the duration required for the healing of a medial collateral ligament?

For athletes who wish to continue playing sports, physical therapy aimed at increasing knee strength and flexibility is extremely important. While more severe grades of MCL tear can take up to 12 weeks to heal, moderate MCL sprains usually heal in 3–4 weeks.

Can an MCL tear heal completely?

A grade 1 (minor) MCL tear usually heals in one to three weeks. A grade 2 (moderate) MCL damage usually requires four to six weeks of treatment. A grade 3 (severe) MCL injury may require up to six weeks of treatment.

Does walking help people with MCL sprains?

Many physicians and physical therapists advise walking as an exercise to help reduce pain and stiffness after an MCL sprain, particularly if it is a grade II sprain. Since the MCL supports the knee, it’s imperative to begin walking as soon as possible after an injury. Walking aids in the healing process for MCL sprains.

References

- Patel, D. (2023, April 11). Medial Collateral ligament Sprain. Samarpan Physiotherapy Clinic. https://samarpanphysioclinic.com/medial-collateral-ligament-sprain/

- Physiotherapist, N. P.-. (2023, December 13). Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) injury: Cause, treatment. Mobile Physiotherapy Clinic. https://mobilephysiotherapyclinic.in/medial-collateral-ligament-injury/

- MCL Tear. (2025, March 19). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21979-mcl-tear

- Medial collateral ligament (MCL) injuries (for teens). (n.d.). https://kidshealth.org/en/teens/mcl-injuries.html

- Schwartz, A. A. (2023, December 19). MCL tear: symptoms and recovery. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/pain-management/knee-pain/mcl-injury-what-to-know