Long Thoracic Nerve

Introduction

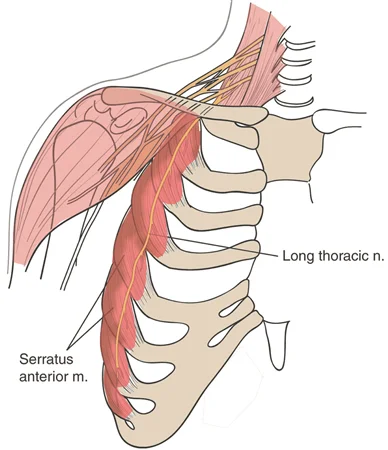

The long thoracic nerve arises from the C5-C7 nerve roots and innervates the serratus anterior muscle. It plays a crucial role in scapular stability, preventing winging of the shoulder blade. Injury to this nerve can result in scapular winging, weakness in shoulder protraction, and difficulty in overhead movements.

The serratus anterior muscle, one of the key muscles for rotating the scapula to enable overhead arm raising, is innervated by the long thoracic nerve. Serratus anterior muscle paralysis and a condition called a winged scapula can result from injury to the long thoracic nerve, which supplies the muscle’s only motor innervation.

Structure

The long thoracic nerve controls the serratus anterior muscle, which pulls the scapula forward around the thorax to enable arm anteversion and raises the ribs to aid in breathing, Additionally, the serratus anterior inferior controls the scapula’s anterolateral mobility, which permits arm elevation.

After passing anterior to the scalenus posterior muscle, the long thoracic nerve travels inferiorly on the chest wall along the mid-axillary line on the outer surface of the serratus anterior muscle for about 22 to 24 centimeters. The nerve lies posterior to the first part of the axillary artery and from where it emerges to the posterior angle of the second rib, it travels at a posterior angle of around 30 degrees concerning the anterior axillary line. It then passes between the posterior and middle axillary lines.

The C5 and C6 nerve roots constitute the top part of the long thoracic nerve, whereas the C7 nerve root creates the bottom part. In the axilla, these two sections fuse. The long thoracic nerve’s upper division passes close to the suprascapular nerve in the supraclavicular area, running parallel to the brachial plexus.

Function

The long thoracic nerve is a motor nerve that supplies innervation to the serratus anterior muscle. This muscle raises the ribs to aid in breathing and drags the scapula anteriorly, enabling anteversion of the arm. To enable prolonged upward rotation of the scapula, which is necessary for overhead lifting, the serratus anterior also supports the trapezius muscle.

Damage to the long thoracic nerve paralyzes the serratus anterior muscle, which results in a winged scapula because it is the sole nerve that innervates this muscle.

A unique trait of the long thoracic nerve is its superficial run over the full length of the serratus anterior muscle it feeds. The nerve subsequently splits into smaller branches that lie parallel to the main trunk before turning at right angles and supplying innervation to the individual slips by arriving via the superior aspect of the slips.

At the proximal border of the distal serratus anterior head, a collateral branch of the thoracodorsal artery—the serratus anterior branch—joins the long thoracic nerve. It then passes across the nerve and splits into the terminal muscle branches. Known as Crow’s feet, this point is important because it serves as a marker during flap transfer procedures.

Course

The brachial plexus, which emerges from the anterior rami of spinal nerves C5, C6, and C7, includes the long thoracic nerve as a lateral branch. The long thoracic nerve’s trunk is formed by these nerve roots, which extend deep into the scalenus medius muscle.

Nearly the whole nerve’s path is readily visible in cadavers because of its rather superficial placement. When the nerve emerges, its trunk descends anteriorly to the scalenus posterior muscle and posteriorly to the brachial plexus, axillary artery, and axillary vein.

Deep to the clavicle and superficial to the first and second ribs, the long thoracic nerve runs laterally and distally. It stops on the superficial aspect of the serratus anterior muscle after continuing in the mid-axillary line along the anterior thoracic wall.

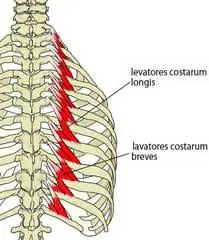

Muscle Supply

The serratus anterior muscle, sometimes referred to as the “boxer’s muscle,” is innervated only by the long thoracic nerve. Damage to this nerve causes the muscle to become paralyzed, a condition known as a winged scapula. When punching, the scapula protracts a movement that is mostly controlled by the serratus anterior. Overhead lifting requires the scapula to rotate upward for an extended period, which is made possible by the serratus anterior and trapezius muscles.

Depending on its origins and locations of insertion, the serratus anterior muscle, which is situated deep to the subscapularis, is separated into three parts: the serratus anterior superior, serratus anterior intermediate, and serratus anterior inferior. As a result, depending on the muscle component, the serratus anterior has different innervation.

In addition to the long thoracic nerve itself, the superior segment is innervated by an isolated branch that is not connected to the main trunk. Remarkably, the independent branch’s path resembles that of the nerves innervating the levator scapulae muscle, indicating a connection between the levator scapulae muscle and the serratus anterior superior. The inferior segment is innervated by both the long thoracic nerve and a branch of the intercostal nerve, whereas the serratus anterior intermediate is innervated by the long thoracic nerve.

Anatomical Variation

Although the anterior rami of the C5, C6, and C7 roots of the brachial plexus are normally where the long thoracic nerve originates, in around 10% of people, the nerve also receives input from the C8. There is evidence of an abnormal relationship between the dorsal scapular nerve and the long thoracic nerve. Additionally, it is known that C6 and C7 make up the majority of the long thoracic nerve, which is normally composed of the three ventral rami of the cervical nerves C5, C6, and C7. In other cases, the long thoracic nerve’s C5 component was missing, although fibers from C5 were thought to be carried via a connecting branch from C6.

Furthermore, the C5, C6, and C7 components usually connect in the axillary area to create the long thoracic nerve. Nonetheless, the confluence of these long thoracic nerve components has been documented to occur posterior to the clavicle, above the axillary area. When treating thoracic outlet syndrome and clavicular fractures, this physiological variation makes patients more vulnerable to nerve damage.

Examination

- Computed tomography (CT) scan

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Electromyogram (EMG) and nerve conduction studies

- Myelogram

Clinical Importance

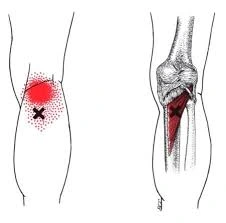

Winging of the scapula and weakening of the serratus anterior are caused by denervation of the long thoracic nerve. Scapula winging may result from any weakening or dysfunction in any of the muscles that support and stabilize the scapula. The most common cause of winging is a weakening of the serratus anterior muscle, which results in weak scapular protraction, unopposed medial scapular retraction by the rhomboid muscles, and elevation by the trapezius. Because of the weakening of the trapezius muscle, which is supplied by the spinal accessory nerve, this disease may be clearly distinguished from the far less frequent lateral winging.

The long thoracic nerve has a relatively smaller diameter than other brachial plexus nerves. This, along with its superficial course along the serratus anterior muscle surface and minimal connective tissue, makes it more vulnerable to damage, either surgically or non-operatively, which can lead to the development of scapular winging. The long thoracic nerve is comparatively exposed from the axilla down and extends to the eighth or ninth rib level.

As a result, the nerve may be exposed to extrinsic harm such as Saturday night palsy, crutch use, anesthesia, or compression from a cast. Additional non-surgical causes of nerve damage include bearing a lot of weight, compression from the fascial sheath, second rib, or middle scalene muscle, entrapment in the middle or posterior scalene muscles, nerve traction from sports, overuse from unfamiliar gardening or household tasks like digging, compression from heavy backpack shoulder straps and infrequently, chiropractic manipulation.

Scapular winging can be caused by passive arm extension and uncontrolled scapular motions during sports, such as abrupt shoulder jerking, which can stretch the long thoracic nerve and its blood vessels. It has been observed that less scapular motion is needed to compress or stretch the long thoracic nerve the closer it is to the scapula’s lower angle. The varying incidence of serratus anterior paralysis may be explained by individual variances in the distance between the nerve and the scapula.

Surgical Importance

Winged scapula is a condition caused by paralysis of the serratus anterior or trapezius muscles in cases of injury to the long thoracic nerve. The long thoracic nerve is more likely to sustain proximal damage from thoracic procedures such as radical mastectomy, transthoracic sympathectomy, trans axillary thoracotomy, misplaced intercostal drains, video thoracoscopy port insertion, axillary lymph node dissections, chest tube placements, and first rib resection.

Furthermore, young infants are vulnerable to long thoracic nerve damage and subsequent scapular winging when they receive a posterolateral thoracotomy incision for closed heart surgeries or any other surgery that requires the separation of the serratus anterior muscles from the latissimus dorsi.

Therefore, knowing the long thoracic nerve’s anatomical path is crucial for improving surgical success rates and lowering the possibility of inadvertent nerve injury. Since the nerve roots can be located anteriorly, posteriorly, or through the middle scalene muscle, physiological variations in the long thoracic nerve location to the middle scalene muscle may result in iatrogenic nerve damage and consequent scapular winging.

Additionally, the serratus anterior muscle does not work in unison with the other shoulder girdle muscles when the scapula is winged. This disorder makes the scapula more likely to move abnormally about the long thoracic nerve. For example, the shoulder girdle muscles are less controlled while a patient is under general anesthesia, and the scapula may move anteriorly as a result of passive adduction of the arm, which occurs when a patient raises and crosses their arm over their chest. The long thoracic nerve and its blood supply may be compressed, and the muscle may begin to crease.

FAQs

Which nerve is known as the nerve of Bell?

long thoracic nerve

Originating from the top part of the superior trunk of the brachial plexus, the long thoracic nerve—also known as the external respiratory nerve of Bell or the posterior thoracic nerve—usually gets input from cervical nerve roots C5, C6, and C7.

Can a long thoracic nerve be cured?

Long thoracic nerve dysfunction can happen without damage or as a result of trauma. Thankfully, most patients who get conservative therapy have a restoration of serratus anterior function; however, recovery might take up to two years.

What damages the long thoracic nerve?

This nerve can be paralyzed by nontraumatic causes as well: immunizations, vitamin deficiency diseases, metabolic disorders, toxins, Parsonage-Turner syndrome, isolated neurites, viral and nonviral diseases (like parvovirus, leprosy, diphtheria, tetanus, and poliomyelitis), and compressions.

What is the recovery time for long thoracic nerve surgery?

The focus will be on correcting biomechanical faults and reactivating, strengthening, and endurance of the serratus anterior and scapular musculature. Due to the delicate nature of nerves, full recovery can take 6-12 months.

How do you test for long thoracic nerve injury?

The serratus wall test entails the patient pushing against a wall with flat hands at waist level while facing a wall that is about two feet distant. Winging (medial winging) of the scapula due to paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle would be the result of damage to the long thoracic nerve.

What is the root of the long thoracic nerve?

The serratus anterior muscle, which serves to secure the scapula to the chest wall, is innervated by the long thoracic nerve, which emerges from the C5–C7 roots. Winging of the scapula can result from injuries to this nerve, particularly when the arm is in anterior abduction.

References:

- Long thoracic nerve. (2023, October 30). Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/long-thoracic-nerve

- Professional, C. C. M. (2024i, December 19). Thoracic spine. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/22460-thoracic-spine

- Long thoracic nerve. (2023, July 24). StatPearls.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535396/