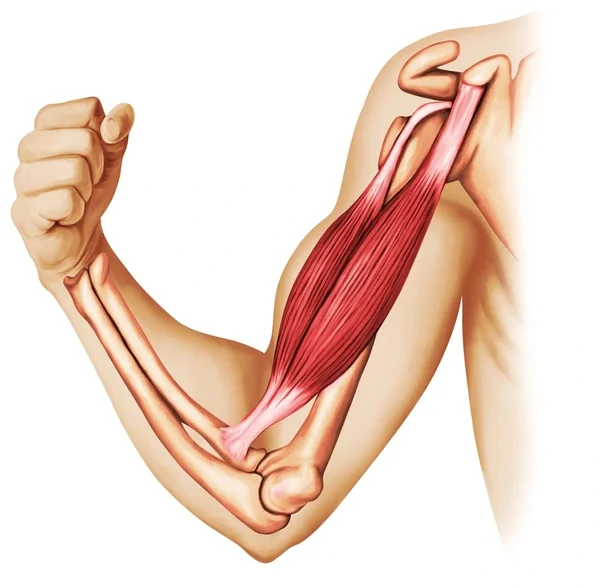

Biceps Brachii muscle

The biceps brachii muscle, commonly referred to as the biceps, is a prominent muscle located in the upper arm, specifically the anterior compartment.

It is one of the most recognizable muscles in the human body and plays a crucial role in both anatomical function and aesthetic appearance.

What are the Bicep Brachii Muscles?

On the ventral side of the upper arm, the biceps brachii, also known as the “biceps,” is a massive, thick, fusiform muscle. The proximal connection of this muscle has two heads, as the name suggests. While the long head is also known as “caput longum,” the small head is occasionally referred to as “caput breve.”

The biceps brachii extends distally as the bicipital aponeurosis, spanning the elbow joint and inserting onto the forearm and radius fascia. When this muscle is extended, it is a forearm flexor; when it is flexed, it becomes the strongest supinator in the forearm.

Problems with the biceps brachii are frequently caused by trauma or overuse of the muscles. For example, persistent wear and tear can rupture the long head tendon, causing the “popeye deformity,” which is prevalent in baseball pitchers.

As a result, the muscle at the anterior mid-arm creates a ball. When doing a physical examination or ultrasound-guided arterial cannulation, the biceps brachii serves as a crucial landmark for finding the brachial artery.

The anatomy and clinical significance of the biceps brachii are covered in this article.

Anatomy

The brachialis, brachioradialis, and coracobrachialis are the other three muscles that make up the upper arm, together with the biceps.

A united muscular belly is formed by the joining of the two heads at the middle arm. Despite cooperating to move the forearm, the heads are physically separate and do not share any fibers.

The heads spin ninety degrees as they extend downhill into the elbow, attaching to the radial tuberosity, a rough projection located directly below the radius neck.

The biceps is the only muscle of the other three that makes up the upper arm that crosses over into the elbow and the glenohumeral (shoulder) joints.

Structure

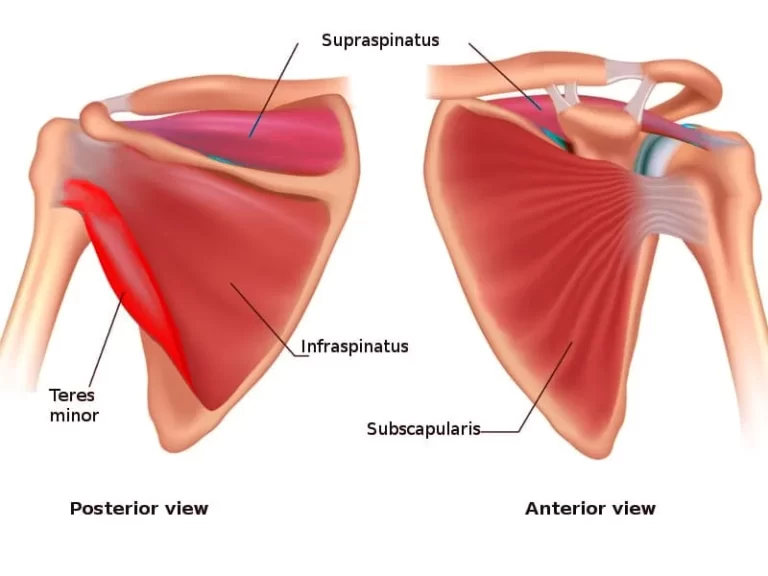

Along with the brachialis and coracobrachialis muscles, which share a nerve supply, the biceps is one of three muscles in the anterior compartment of the upper arm. The coracoid process and supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula, respectively, are the origins of the short and long heads of the biceps muscle, respectively.

The long head originates on the glenoid and continues to be tendinous as it travels through the humerus’s intertubercular groove and the shoulder joint. The tendon of the short head extends from its origin on the coracoid and forms the conjoint tendon with the tendon of the coracobrachialis.

The biceps muscle crosses the elbow and shoulder joints, in contrast to the other muscles in the anterior compartment of the arm.

A common muscle belly is formed when the two heads of the biceps unite in the middle of the upper arm. However, many anatomic studies have shown that the muscle bellies are separate structures without confluent fibers. This is typically near the deltoid muscle insertion.

The two heads rotate outward by ninety degrees as the muscle extends distally, and then they insert onto the radial tuberosity. While the long head inserts proximally closer to the tuberosity’s apex, the short head inserts distally on the tuberosity.

The bicipital aponeurosis, also known as the lacertus fibrosus, is a thick band of fascia that extends over and inserts into the ulnar portion of the antebrachial fascia, organizing around the biceps’ musculotendinous junction.

The bicipitoradial bursa, which surrounds the tendon that joins to the radial tuberosity, either partially or prevents friction between the biceps tendon and the proximal radius during forearm pronation and supination.

Underneath the biceps brachii are two muscles. These are the brachialis muscle, which attaches to the ulna and runs along the mid-shaft of the humerus, and the coracobrachialis muscle, which, like the biceps, attaches to the coracoid process of the scapula.

In addition to them, the brachioradialis muscle inserts on the radius bone, albeit more distally, and is located next to the biceps.

Function

Three joints are used by the biceps. The ability to flex the elbow and supinate the forearm is the most crucial of these movements. In addition, the long head of the biceps stops the humerus from moving upward. For further information, the acts are, by joint.

Proximal radioulnar joint of the elbow: The biceps brachii is responsible for the forearm’s strong supination, or upward turning of the palm. This motion necessitates at least partial flexion of the elbow’s humeroulnar joint, which is assisted by the supinator muscle.

The supinator muscle is the main source of supination when the humeroulnar joint is fully stretched. Because the biceps link distally to the muscle at the radial tuberosity—the side of the bone opposing the supinator muscle—they are an especially strong supinator of the forearm. Together with the supinator muscle, the flexed biceps efficiently return the radius to its neutral supinated position.

Elbow’s humeroulnar joint – The biceps brachii is a key forearm flexor, especially when the forearm is supinated. Practically speaking, this motion is used to lift something, like a grocery bag, or to curl your biceps. The brachialis, brachioradialis, and supinator work together to flex the forearm while it is in pronation, or with the palm facing the ground.

The biceps brachii play a less significant role in this movement. The brachioradialis shows a far larger position-dependent variation in exertion than the biceps during concentric contractions, although the force produced by the biceps brachii stays constant regardless of the forearm’s orientation (supinated, pronated, or neutral). That is, other muscles must adjust to compensate for variations in forearm position because the biceps can only produce so much force.

The glenohumeral joint, often known as the shoulder joint, has several weaker roles. The biceps brachii only marginally contributes to the shoulder joint’s forward flexion, or raising the arm forward. When the arm is externally (or laterally) rotated, it might also help in abduction, which is the act of bringing the arm out to the side.

Lastly, when a large weight is carried in the arm, the short head of the biceps brachii helps to stabilize the shoulder joint because of its attachment to the scapula, or shoulder blade. The biceps tendon plays a crucial role in maintaining the humerus’s head in the glenoid cavity.

Elbow flexion preferentially activates the motor units in the lateral part of the long head of the biceps, whereas forearm supination preferentially activates the motor units in the medial region.

The biceps are commonly associated with strength in many cultures around the world.

Embryology

In the fourth week of development, the cellular progenitors of the limb muscles move from the somites into the limb buds.

While the local limb bud cells generate the tendons and other connective muscle tissue, the somites give rise to the muscle fibers. Myocyte production happens soon following the development of the skeletal components.

There is a single muscular mass from which the biceps, coracobrachialis, and brachialis muscles originate. With scapular development, the two heads of the biceps brachii split at their proximal insertions.

Until the distal part of the common muscle mass separates, which happens after proximal muscle segmentation, it may be difficult to tell the difference between the brachialis and bicep.

Blood supply

The brachial artery provides blood to the biceps. Since the artery travels medial to the tendon in the cubital fossa, the distal tendon of the biceps can be used to palpate the brachial pulse.

Nerves Supply

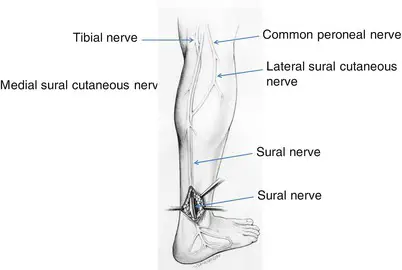

The biceps receive their sensory and motor innervation from the musculocutaneous nerve. This nerve is a terminal branch of the lateral cord of the brachial plexus, originating from the C5 and C6 spinal roots.

The musculocutaneous nerve passes through the coracobrachialis, the inferior border of the pectoralis minor, and the brachialis and biceps in a distal direction.

After passing through the cubital fossa, this nerve becomes the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm.

Anatomical Variations

Thirty percent of adults differ somewhat in where their biceps originate. In several individuals, the humerus may develop a third head. But between two and five percent of people may have three to seven extra heads of the biceps.

About 20% of people have bifurcated distal biceps tendons, while about 40% have a detached tendon. There is no negative impact on arm function from these changes.

Surgical Considerations

During arm movement, the synovial sheath enclosing the biceps long head tendon travels back and forth in the bicipital groove.

The long head tendon is often inflamed due to this process. Tenotomy and tenodesis are the typical treatments used to treat advanced tendinopathy of the long head of the biceps.

Biceps Tenotomy

The degree of biceps tendon damage can be estimated with the use of an arthroscopy. Gross biceps long-head tendon pathology can be classified intraoperatively using the Lafosse grading scale, which uses the following system:

- Grade 0: Normal tendon

- Grade 1: Minor lesion

- Grade 2: Major lesion

Only 25% to 50% of injured tendons are debrided by certain surgeons. When there is a more significant disease, an arthroscopic biceps tenotomy is recommended. This procedure involves releasing the tendon as close to the superior labrum as feasible.

If soft tissue adhesions are not preventing the tendon from retracting distally toward the bicipital groove, it should do so. To facilitate retraction after tenotomy, the tendon needs to be mobilized if adhesions are present. Hypertrophy of the biceps long head tendon and scarring of other shoulder joint tissues are possible causes of postoperative discomfort.

Biceps Tenodesis

When biceps long-head tendon instability is present, this surgery is preferred over tenotomy. Younger patients, athletes, laborers, and those with particular concerns about postoperative cosmetic abnormalities, like the popeye deformity, are better candidates for biceps tenodesis.

Tenodesis minimizes the risk of postoperative muscular atrophy, exhaustion, and cramping while optimizing the length-tension relationship of the biceps muscle.

Clinical Significance

The first line of treatment for pathologic diseases affecting the proximal and distal biceps brachii tendons is frequently inoperative. This article does not include conditions affecting the distal biceps brachii tendon.

The goals of rehabilitation are to increase periscapular stability, rotator cuff strength, and shoulder range of motion in addition to restoring muscle balance across the shoulder girdle.

The following therapies may be taken into consideration for ailments affecting the proximal aspect of the long head of the biceps tendon:

Exercises for strengthening and extending the proximal biceps during physical therapy

Utilizing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications for pharmacologic therapy Iontophoresis with dexamethasone, for example

It’s also advisable to think about focused stretching of the pectoralis minor and other anterior shoulder regions. Early animal studies have demonstrated the promise of modalities such as dry needling. Severe or refractory conditions call for surgery.

Exercise for Biceps muscle:

Stretching exercise of the Biceps muscle

Following are the Best Biceps Stretching Exercises

Chair Biceps Stretch

This is an amazing, flexible biceps stretch that you can perform in almost any place.

- Biceps Extension in a Chair

- Take a seat erect in a dining chair or stool.

- Spread your arms wide, reaching shoulder height, with your palms facing up.

- Return your arms behind you slowly until you feel an upper arm stretch.

- Hold for 20 to 30 seconds, then do so three times.

Seated Biceps Stretch

With the entire body fixed this seated biceps stretch is an excellent method to manage and advance the stretch effectively to target the biceps muscles.

- Legs extended in front of you, knees slightly bent, feet flat on the ground, take a seat on the floor.

- With your fingers pointing away from your body, place your hands behind you.

- Slide your butt forward slowly, away from your hands, until your biceps start to stretch.

- Hold for 20 to 30 seconds, then do so three times.

Hand Clasp Bicep Stretch

The hand clasp is a very easy and powerful way to extend your biceps.

- Place your fingers together behind your back while standing.

- Draw your shoulder blades together and flex your shoulders downward.

- Lift your arms back slowly and press down through your hands toward the ground until you feel a stretch.

- Take a 30-second hold, then repeat three times.

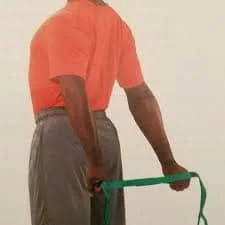

Biceps Stretch With Strap

The strap acts as an anchor to assist you to stretch both sides of your biceps at the same time.

- Place your hands hip-width apart and grasp a strap, belt, or stick behind you with your palms facing back.

- Raise your arms behind you as demonstrated, keeping your elbows straight, and feel for a stretch on the front of your shoulders.

- Hold for ten seconds, then ten times repeat.

Wall Biceps Stretches

When varying the hand’s posture, this exercise is excellent for extending the various biceps muscles.

- Place your feet shoulder-width apart and stand close to a wall.

- Put your back against the wall behind you and your arm against it.

- Aim for shoulder height as you carefully glide your hand up the wall while keeping your elbow straight.

- Your upper arm and the area across the front of your elbow should feel stretched.

- Take a 30-second hold, then repeat three times.

Doorway Biceps Stretch

This doorway stretch is a great, powerful method to work your biceps.

- Place your hand at shoulder height on the door frame or jamb while standing in an open doorway.

- Keeping your grip on the door frame, take a step forward until your elbow is straight.

- Feel the strain in your biceps as you slowly rotate your entire body away from the arm you are stretching.

- Take a 30-second hold, then repeat three times.

Strengthening exercise

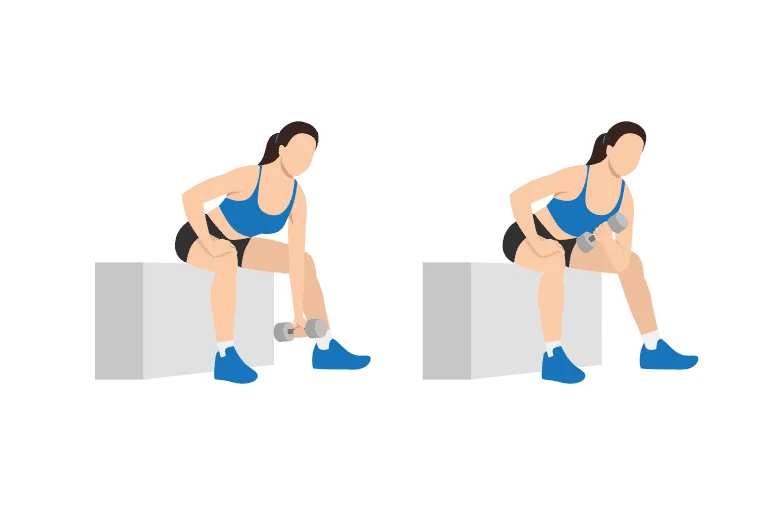

concentration curl

With your legs extended in a V form, sit at the end of a level bench.

Lean a little forward and take hold of a dumbbell with one hand.

Place your elbow on the inner thigh, palm toward your center.

For support, place your other hand or elbow on the opposing thigh.

Curl the weight gradually in the direction of your shoulder without moving your upper body.

To finish the curl with your palm toward your shoulder, turn your wrist slightly as you rise.

After a brief period during which you can feel the strain in your bicep, gradually reduce the weight. However, please wait until your last repeat before resting it on the ground.

After 12 to 15 repetitions, switch arms.

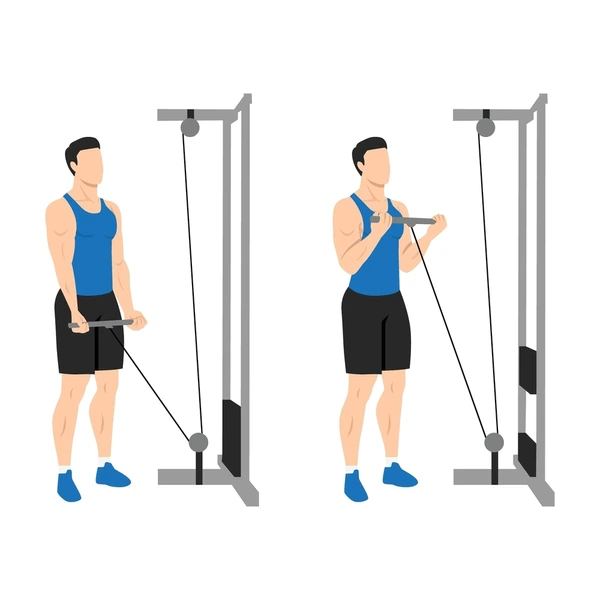

Cable curls

With your elbow near your side and your palm facing forward, grab the cable handle while standing a few steps away from the pulley machine.

For improved balance, position the foot that is opposite your curling hand slightly ahead of the other foot.

Curl your arm slowly so that the palm of your hand is facing your shoulder.

Feel the strain in your biceps as you hold the curl up for a brief period.

Lower the handle to the beginning position gradually.

Perform 12 to 15 reps, then exchange arms.

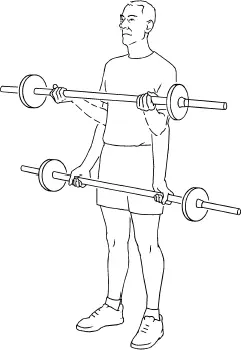

Barbell Curl

As you stand, stretch your feet shoulder-width apart.

With your arms by your sides and your palms facing out, grasp the barbell.

Curl the barbell slowly in the direction of your chest while exhaling.

Lift the barbell with just your arms while maintaining a straight chest.

After a brief moment of holding the posture, gradually bring the barbell back down to its initial position.

Do this twelve to fifteen times.

Chin up

With your palms facing you, raise both of your arms while standing beneath the chin-up bar.

Using both hands, grab the bar. To get to the bar, you might have to leap or stand up.

Steady your body with a tight grasp and your thumbs wrapped around the bar. Crossing your legs could provide you extra stability.

Bend your elbows to bring your torso upward as you slowly release the air.

As you concentrate on allowing your biceps to pull you up to where your chin contacts the bar, keep your elbows in front of you.

After a little pause, slowly return to the beginning position and then act once more.

FAQ

What are bicep muscles?

Large muscles in the front of the upper arm, between the shoulder and the elbow, are called biceps. The principal function of the muscle is to rotate the forearm and flex the elbow. It is sometimes referred to by its Latin name, biceps brachii, which means “two-headed muscle of the arm”.

Which bicep is better?

Conversely, it is simpler for someone to build biceps if they are long and reach far down the forearm. The apex (the top of your biceps when contracted) is the single benefit of having short biceps. The top of the long biceps is less prominent.

Are there 2 types of biceps?

The biceps brachii and biceps femoris are found in humans. One noticeable muscle on the front of the upper arm is the biceps brachii. It comes from the upper glenoid cavity, which is the hollow for the shoulder joint, and the coracoid process, which is a projection of the scapula (shoulder blade).

Are bigger biceps attractive?

Most college women nationwide who participated in a HerCampus.com survey regarded their arms as the top turn-on. Women acknowledge that they enjoy seeing a man’s biceps peeking out from under a sweater or t-shirt because they think it shows that he takes good care of his body.

Can I get biceps in 2 weeks?

You can’t necessarily acquire huge arms fast because building muscle requires time and commitment. However, according to Gargano, with consistent programming that gradually increases load and intensity, you should start to see changes in your arm strength and size in approximately four weeks.

What is the strongest muscle shape?

If one were to define strength as the capacity to apply the greatest amount of force, the masseter muscle would be the strongest in the human body. You likely refer to the masseter as your jaw muscle. When you chew, the broad cheek muscle near the back of your jaw opens and shuts.

How many months to increase biceps size?

It usually takes six to eight weeks for you to notice a difference in the way your arms look. You should usually start to notice more noticeable changes at about the 12-week point, particularly if you didn’t have a lot of muscle growth in that area to begin with.

Does the chest grow faster than the biceps?

Because the chest muscle is so big, it usually grows faster. It will also take longer for the biceps to heal. Having said that, to see rapid improvements in both, you should continue to eat, sleep, and exercise properly.

What causes bicep pain and weakness?

Many factors can lead to bicep pain. These consist of fractures, brachial plexus injuries, and biceps tendinitis. Upper arm and elbow pain, which occasionally spreads to the forearm, are among the symptoms. Some persons have restricted mobility or edema.

How to relieve bicep pain?

Rest.

Taking a vacation from the sport or activity that triggered the issue.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Physical therapy and exercises.

Cortisone injections.

Platelet-rich plasma.

15 Comments