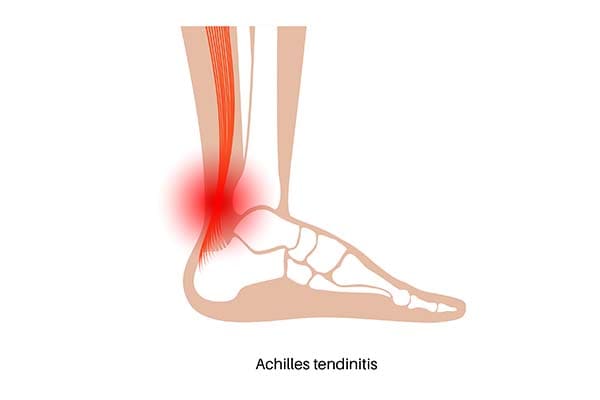

Achillis Tendonitis

What is Achillis tendinitis ?

Achilles Tendonitis is an overuse injury that causes inflammation of the Achilles tendon—the band of tissue connecting the calf muscles to the heel bone. It commonly occurs in runners or individuals who suddenly increase the intensity or duration of physical activity.

Symptoms include pain and stiffness along the back of the heel, especially in the morning or after exercise. Early treatment involves rest, ice, stretching, and strengthening exercises to reduce inflammation and prevent further injury.

Since Achilles tendinopathy is idiopathic, its exact cause is unknown. A sedentary lifestyle, high-heeled shoes, rheumatoid arthritis, drugs from the fluoroquinolone or steroid family, and usage like jogging are some of the theories of cause. Symptoms and inspection are often used to make the diagnosis.

There is little to no scientific evidence to support the suggested treatments for tendinopathy, which include stretching before exercise, calf muscle strengthening, avoiding overtraining, modifying running mechanics, and choosing appropriate footwear. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), rest, ice, and physical therapy are examples of nonspecific, symptomatic treatment. Surgery may be provided to those who are dissatisfied with symptomatic therapy.

Anatomy of Achillis Tendon

Two tendinous segments make up the Achilles tendon. A single, homogeneous tendon is formed by the progressive merging of two tendon locations, one proximally and the other distally. It consists of three muscle heads: the plantaris and gastrocnemius are biarticular, whereas the soleus is monoarticular. There are two locations where the tendon’s mechanical stress is focused. These are the middle segment of the tendon, which is the most often injured area, and the medial or center section of the paratenon.

The Achilles tendon rotates 90 degrees as it descends from its origin, twisting clockwise on the left and counterclockwise on the right. As a result, bigger gastrocnemius fibers insert posterolaterally, while smaller soleus fibers enter anteromedially.

It is believed that this arrangement influences the pathophysiologic processes of Achilles tendinopathies and contributes to a change in the tendon’s biomechanics.

Fatty infiltration, capillary growth, and the loss of strong parallel collagen I fibers are the hallmarks of tendon degeneration in cases with insertional Achilles tendinopathy. In advanced imaging, this appears as a thickening of the tendon and will be covered in more detail in the next sections.

Epidemiology

In athletes, the total lifetime injury incidence for the Achilles tendon is about 24 percent. The frequency of running-related injuries ranges from 11% to 85%, or 2.5 to 59 injuries for every 1,000 hours of running. According to one study’s findings, 1–2% of competitive adolescent players had Achilles tendinopathy.

According to a different survey, 9% of leisure athletes have injuries. A lifetime injury incidence of 2.35 per 1000 is closely linked to participation in sports. In elderly males, this incidence rises. The majority of Achilles tendinopathy ruptures occur in males, with a male-to-female ratio of 3.5:1, while the total incidence rate is 2.1 per 100,000 person-years.

Pathophysiology of Achilles tendonitis

Two tendinous segments make up the Achilles tendon. A single, homogeneous tendon is formed by the progressive merging of two tendon locations, one proximally and the other distally. It consists of three muscle heads: the plantaris and gastrocnemius are biarticular, whereas the soleus is monoarticular. There are two locations where the tendon’s mechanical stress is focused. These are the middle segment of the tendon, which is the most often injured area, and the medial or center section of the paratenon.

The Achilles tendon rotates 90 degrees as it descends from its origin, twisting clockwise on the left and counterclockwise on the right. As a result, bigger gastrocnemius fibers insert posterolaterally, while smaller soleus fibers enter anteromedially. It is believed that this arrangement influences the pathophysiologic processes of Achilles tendinopathies and contributes to a change in the tendon’s biomechanics.

Fatty infiltration, capillary growth, and the loss of strong parallel collagen I fibers are the hallmarks of tendon degeneration in instances with insertional Achilles tendinopathy. In advanced imaging, this appears as a thickening of the tendon and will be covered in more detail in the next sections.

Causes of Achillis tendonitis

The first stage of the tendon continuum is called a reactive tendon, and it is characterized by a proliferative, non-inflammatory reaction in the cell matrix. Tensile or compressive overload is the cause of this. One of the main pathogenic triggers has been identified as straining the tendon during exercise, and a microtrauma can result from systematically pushing the Achilles tendon beyond its normal limit.

Frictional pressures between the fibers and aberrant concentrations of loading in the Achilles tendon are caused by repetitive microtraumas that are associated with an uneven tension between the gastrocnemius and soleus. Degeneration, tendon sheath inflammation, or a mix of the two are possible outcomes of this. Insufficient recuperation time may result in tendinopathy.

Several reasons have been proposed as potential causes of chronic tendon overuse injuries and tendon degeneration, including reduced arterial blood flow, local hypoxia, decreased metabolic activity, poor nutrition, and a prolonged inflammatory response.

Pronation of the foot

Ankle malalignment caused by overpronation of the foot is the most prevalent and possibly the most significant. It has been suggested that Achilles tendinopathy is linked to increased foot pronation.

While overuse injuries typically have a complex cause, acute trauma is mostly caused by external sources. rapid overload, abrupt trauma, or rapid muscular exhaustion can all result in Achilles tendinopathy’s acute phase, which is marked by edema development and an inflammatory response. A fibrin may develop and adhesions may form off the tendon if the acute phase is not well treated or is ignored.

If the tendon is not offloaded and allowed to return to its natural state, reactive tendinopathy may worsen and eventually lead to tendon deterioration. It has been demonstrated that the continued increase in protein synthesis during this phase causes the collagen to separate and the cell matrix to become disorganized. Similar to the first phase, this effort at tendon repair involves more physiological breakdown and participation.

The last step on the continum is degenerative tendinopathy, which is thought to indicate that the tendon’s prognosis is bad and that the alterations are permanent. Although peri-tendinous adhesions and tendon degeneration are frequently observed together, this does not imply that one disease causes the other.

Signs and Symptoms of Achillis tendonitis

The symptoms might range from a burning sensation around the whole joint to a localized aching or pain and swelling in one or both ankles. In this disease, the tendon and joint region may become stiff the next day as swelling impinges on the tendon’s mobility, and the discomfort is often greatest during and after activity.

Based on the site of discomfort, Achilles tendon injuries can be classified as proximal musculotendinous junction (9%–25%), midportion tendinopathy (55%–65%), or insertional tendinopathy (20%–25% of the injuries).

Risk Factors of Achillis tendonitis

The pathophysiology of Achilles tendinopathy is associated with some identified risk factors. Among these risk factors are, among others:

- Being overweight

- High blood pressure

- Type II Diabetes

- Extended usage of steroids

- History of tendinopathy in the family

- The older population and improper footwear are other problems.

Diagnosis

Assessment

Physical examination is the primary method used to diagnose Achilles tendinopathy. Standing and in a prone posture, the patient should be assessed for certain clinical indicators of Achilles tendon localized pain, focal or diffuse sensitivity, edema, stiffness, and felt rigidity. Clinical examinations consist of:

Arc sign: When the ankle joint is manipulated in plantarflexion and dorsiflexion, swelling or nodules inside the tendon are felt. When the nodules or swelling move with the range of motion, a positive arc sign is seen. The region of greatest thickening stays stationary in one place when paratendinopathy is present.

The Royal London Hospital test involves placing the ankle in a neutral posture and palpating the location of highest discomfort. After that, the patient is told to vigorously dorsiflex and plantarflex their ankle joint. When the ankle joint is in its maximal plantarflexion and dorsiflexion, the previously most painful spot is palpated once more. When the tendon is under strain, the discomfort either drastically reduces or goes away, indicating tendinopathy.

Tests for Achilles Tendinopathy Diagnosis:

X-rays of the lateral and axial calcaneus may show bony prominences in the upper part of the calcaneus or calcifications in the proximal extension of the tendon insertion. Additionally, pathological bone cancers can be ruled out by X-rays.

An effective method for analyzing tendon damage and determining the likelihood of tendinopathy and rupture is ultrasound. Increased Achilles tendon thickness, hyperemia linked to hypervascularity, a decrease in the gastrocnemius-soleus rotation angle, and a shortening of the Kager fat pad are some of the details it could reveal.

In the course of interventional therapy, ultrasound is also helpful. In addition to being readily accessible with a substantial amount of tissue, an ultrasound may be used to dynamically assess the Achilles tendon’s range of motion.

The distal part of the tendon exhibits a hypoechoic region and a lack of fibrillar appearance due to insertional Achilles tendinopathy.

The mid to proximal portion of the tendon may thicken focally or diffusely in noninsertional Achilles tendinopathy; hypoechoic patches and a lack of compact linear fibrillar appearance are also seen.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging: This imaging technique provides detailed information on the state of joint structures and allows for both static and dynamic views as well as studies in several planes.

On a sagittal MRI, the typical Achilles tendon is less than 7 mm thick from anterior to posterior. Elevated values indicate deterioration and persistent intrasubstance tendinopathy. According to one study, ultrasonography was more sensitive than MRI at identifying early enthesopathy alterations. Nonetheless, a different research showed that assessments of tendon thickness taken using ultrasound and magnetic resonance had excellent agreement.

Distal tendon thickening with a strong signal on fat-suppressed imaging is indicative of insertional Achilles tendinopathy. Heterogeneous signaling on T1 and T2 imaging and thickening of the mid to proximal portion of the tendon are signs of noninsertional Achilles tendinopathy.

Calculated Tomography (CT): In Achilles pathology of insertion, the CT scan can be used to rule out trabecular structural changes of the calcaneus. The patient is exposed to radiation, though.

Treatment of Achillis tendonitis

Depending on whether the condition is acute or chronic, conservative and surgical methods can be used to treat Achilles tendinopathy. Surgery is typically advised when there is a complete rupture.

Conservative Treatment

The following are included in conservation therapy, which is the first line of treatment for Achilles tendinitis:

- Rest.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAID) administration.

- Adjusting footwear and using manual treatment that targets particular local locations can improve the Achilles tendinopathy healing process.

- Since they can reduce pain by 40%, eccentric stretching exercises have to be a part of every physiotherapy regimen. There is some evidence that eccentric exercise is more effective than concentric exercise at reducing pain. When paired with extracorporeal shockwave treatment, eccentric exercises for chronic insertional Achilles tendinopathy are most beneficial; however, they are less effective in individuals with metabolic syndrome.

- Exercise for tendon loading at both short- and long-term follow-up

- Extracorporeal shock wave treatment (ESWT) has improved functioning and quality of life by reducing pain by 60% and achieving 80% patient satisfaction in cases when initial medication is ineffective. Some medical experts use ESWT as their initial therapy since it has been proven to effectively relieve short-term pain and promote tendon repair, earning it a grade B strength of recommendation. The best outcomes have been achieved when ESWT is combined with eccentric workouts.

- When middle-portion Achilles tendinopathy occurs, physiotherapy has been shown to reduce discomfort and increase function. Studies, however, show no preference for one type of exercise over another.Therefore, the use of a splint combined with an eccentric exercise protocol or orthoses to improve pain and function is not currently recommended.

Surgical Management

Ten to thirty percent of patients who do not respond to conservative treatment after six months may elect to have surgery. Surgical techniques and methods might differ and are explained below.

Although there is no data to support it, open debridement endoscopic or minimally invasive techniques produce results that are equivalent to open procedures but have fewer postoperative problems.

Tenax or Topaz: no extra advantage vs open debridement surgery

Resection of the superior calcaneus (Haglund deformity) and bursa: tendinopathy symptoms may be caused by the calcaneal prominence compressing against the bursa, but there have been discussions in recent literature about the connection between calcaneal shape and pain symptoms in this condition. There is no correlation between insertional Achilles tendinopathy and angles recorded in Haglund deformities, such as the Bohler and Fowler-Philip angles.

- Open debridement

- Minimally invasive or endoscopic treatments have comparable outcomes to open procedures, but there is insufficient data to conclude that they are associated with fewer postoperative problems.

- To open debridement surgery, topaz or tenax offer no further advantages.

- Resection of the superior calcaneus (Haglund deformity) and bursa: tendinopathy symptoms may be caused by the calcaneal prominence compressing against the bursa, but there have been discussions in recent literature about the connection between calcaneal shape and pain symptoms in this condition. There is no correlation between insertional Achilles tendinopathy and angles recorded in Haglund deformities, such as the Bohler and Fowler-Philip angles.

- Achilles tendon separation and reattachment : A medial or lateral approach may be used in surgery to separate the central tendon splitting. A lateral takedown strategy led to a statistically significant decrease in the risk of problems, according to a systematic evaluation conducted in 2021.

- Transfer of tendon: The most dependable tendon for repairing or enhancing Achilles tendon deficiency is the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon transplant. It is a great choice for regaining plantarflexion power.

When the FHL is not available, transfers of the tibialis anterior tendon, flexor digitorum longus (FDL), and peronebravis have been documented. - Strayer gastrocnemius recession is not advised for athletes since it considerably lessens discomfort but affects plantarflexion power and endurance.

Physiotherapy Treatment

While engaging in rehabilitation, doctors should urge patients with nonacute Achilles tendinopathy to continue their leisure activities within their pain threshold, since total rest is not recommended. Achilles tendinopathy sufferers may receive advice from clinicians. Some essential components of patient counseling might be:

- Theoretical underpinnings for the use of physical therapy and the function of mechanical loading

- Modifiable risk factors, such as shoe wear and body mass index

- The typical duration of symptom healing.

The fundamental objective of tendinopathy therapy is to enhance the energy storage capacity of the tendon. It is the capacity for the tendon and related muscle to operate and control load, basically serving as a ‘spring’ in storing and then releasing energy. For Achilles tendinopathy, three essential workouts are:

- Loading Isometrically

- Loading that is isotonic

- Loading of energy storage

Phase 1: Achilles tendon holds due to isometric loading

In recent years, there have been significant changes in the way Achilles tendon discomfort is managed. The advent of isometric tendon loading as a cornerstone of tendinopathy therapy is one notable shift. It has been discovered that isometric tendon loading relieves tendon discomfort while preserving a certain amount of baseline strength.

These can be done with one leg or two legs, depending on the symptoms and irritation of the tendons. Double leg holds, which are frequently shorter in length and need fewer repetitions, can be used for extremely irritable (reactive) Achilles tendons. Either the middle or the end of the range—that is, halfway up or straight up on the toes—can be used for the isometric hold.

Phase 2: Calf lifts and isotonic loading

Once the athlete’s degree of discomfort and the tendon’s irritation have decreased, these activities are frequently started. When an athlete should begin isotonic loading for Achilles tendinopathy therapy, there are no “hard and fast” guidelines.

Once their morning tendon stiffness has greatly decreased and they have less than 5/10 pain on NRS or bearable and acceptable discomfort on repeated single leg calf lifts, graduated isotonic loading is started.

Strengthening the tendon and surrounding muscles is the ultimate aim of the isotonic workout. The strength of the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles is crucial when it comes to the Achilles tendon. The tendon matrix and the muscle-tendon unit’s work capacity are not sufficiently adapted by repeated loading, such as occurs during walking or running. Therefore, for the isotonic loaded workouts, greater weights are needed.

- It is possible to conduct isotonic sitting calf raises by gradually increasing the loading. To build tendon tension, perform each repeat for three to six seconds.

- It is best to execute isotonic standing calf raises in the middle of the muscle’s range of motion. Engaging in mid-range heavy slow resistance (HSR) exercises has the advantage of preventing tendon compression at the end of the range, which can happen when using greater loads.

- For instance, the Achilles tendon is vulnerable to compressive stresses on the heel bone (calcaneum) at the very end of the ankle’s plantarflexion (toes pointing) or dorsiflexion (imagine letting the heel drop over the edge of a step) range, which may cause irritation and pain.

Phase 3: Plyometric Exercises for Energy Storage Loading

The start and completion of “energy storage” tendon exercises is the final and most important phase of recovery. These workouts involve leaping and hopping-based activities that distort the tendon. Through the stretch-shortening cycle that occurs when an athlete lands and then pushes off at toe-off, these workouts assist the tendon in regaining its ability to absorb and then release energy.

When the athlete reports little to no morning stiffness in the Achilles tendon upon awakening, these activities can be started. The athlete must also meet certain requirements before beginning these exercises, such as having made good progress with isotonic calf raise exercises, having very little Achilles tendon tenderness when palpated, and being able to handle light running without experiencing a flare-up in tendon irritability or worsening of symptoms.

While increasing speed is more likely to improve power and prepare for sports involving the Stretch Shortening Cycle, increasing length under tension during heavy slow-resistance training, for instance, may put a strain on the tendon and result in higher adaptability.

The following exercises are described:

- The double-leg hop

- Just one leg hop

- Step hops with one leg

- Hopscotch with a ring of activation

Supplementary Treatments

Adjunctive treatments may be used in conjunction with strategies to prescribe exercise therapy and optimize biomechanics. These types of therapy are more often used to manage symptoms than to treat or prevent injuries.

Manual Therapy

Although there isn’t any clinical proof, experts agree that joint mobilizations should be used in the acute phase if the evaluation shows joint limitation. If the evaluation shows joint limitation, there is greater expert-level consensus and a modest amount of clinical data to support the use of joint mobilizations in the chronic stage.

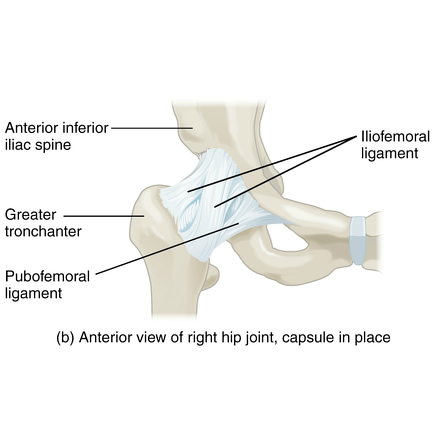

After a thorough examination of the hip, knee, foot, and ankle indicates joint problems, manual treatment may be considered. The talocrural joint’s dorsiflexion constraint and the subtalar joint’s varus- or valgus limitation can both be addressed with ankle mobilizations.

Deep cross frictions have limited outcomes and have not been scientifically demonstrated to be beneficial. The use of soft tissue procedures, including frictions, in the chronic stage is supported by a tiny quantity of clinical data. In the chronic stage, one can think about using soft tissue therapies like frictions.

Electrotherapy

The use of extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) in the chronic stage is supported by contradictory data. Evidence indicates that the results depend more on the energy dosage of the shock wave (EFD ‐ energy flux density = mJ/mm2) than on the kind of shock wave generation (radial vs. focussed ESWT). Additionally, there is proof that the efficacy of ESWT is reduced when an anesthetic is used as part of high energy regimens.

Consequently, it is advised to use low energy ESWT treatments without the need for an anesthetic since they are more affordable, feasible, and comfortable while producing outcomes that are comparable. Both focused and radial ESWT may be performed using low energy ESWT techniques. In the chronic stage, particularly if previous therapies have not worked, think about using ESWT at the following parameters:

- EFD = 0.18 to 0.3 mJ/mm² (2‐4 Bars) is the low energy SWT.

- 2000–3000 shocks

- 15–30 Hz

- Weekly intervals of three to five sessions.

The use of low-level laser therapy and ultrasound is not supported by any clinical data.

Iontophoresis

The use of iontophoresis with dexamethasone in the acute stage is supported by a tiny amount of data, but not in the chronic state. Iontophoresis’s function is currently being studied. A trial of iontophoresis, 0.4% dexamethasone (aqueous), 80 mA‐min, six sessions spread over three weeks, may be considered in the acute stage. If exercise loading is tolerated, iontophoresis should be continued in conjunction with a regimen of concentric-eccentric exercises.

Taping

Expert opinion, not clinical data, supports antipronation tapes. Taping may be considered, maybe before the acute stage of Introduction to Orthotics. When treating patients with Achilles tendinopathy, clinicians should avoid using therapeutic elastic tape to ease discomfort or enhance functional performance. To reduce Achilles tendon tension and/or change foot position in patients with Achilles tendinopathy, clinicians may apply stiff taping.

Night Splints

Encourage the use of braces and night splints during the acute phase. There is a moderate amount of data to support the use of braces and night splints during the chronic stage.

Think about experimenting with night braces and splints during the acute phase but avoiding using them in conjunction with exercise during the chronic phase.

Dry Needling

For patients whose symptoms have persisted for more than three months and whose tendon thickness has grown, clinicians may employ a combination of dry needling, an injection administered under ultrasound supervision, and eccentric activity to reduce discomfort.

Differential Diagnosis

In primary care, posterior heel and ankle pain is a common complaint. People with greater body mass indices and older ages are more likely to have discomfort. When patients do not improve after trying early therapeutic strategies, more research is required.

The following are the most prevalent soft-tissue musculoskeletal conditions linked to posterior ankle pain:

- Retrocalcaneal bursitis is easily detected by MRI or ultrasonography.

Inflammation of the Kager’s fat pad: cause discomfort when the ankle is palpated on both sides, just in front of the Achilles. - An Achilles tendon rupture is indicated by a positive Thompson test result.

- Ultrasonography will reveal fluid and adhesions surrounding the tendon if you have Achilles paratenonitis.

- Forced dorsiflexion and posterior ankle discomfort are symptoms of posterior impingement, also known as Os Trigonum syndrome. Os Trigonum will be seen on plain radiography.

- Calcaneal stress fracture: positive squeeze test.

- FHL tendinopathy: discomfort during the gait’s toe-off phase. On STIR MRI, there is more fluid surrounding the FHL tendon.

- Plantar fasciitis: cause discomfort when the plantar medial calcaneal tubercle is palpated.

Neuroma or nerve entrapment: discomfort that is accompanied by tingling, burning, or numbness. Tinel sign is positive along the sural nerve’s path. - Deep, bruise-like pain in the mid-heel is known as heel pad syndrome.

Acute or persistent discomfort in the posterolateral heel caused by the calcaneus’ prominence is known as Haglund deformity. It can cause inflammation of the retrocalcaneal bursa and frequently necessitates calcaneal excision surgery. - In children and teenagers with underdeveloped growth plates, calcaneal apophysitis is clinically diagnosed as Sever’s disease.

- Insertional calcific tendinosis: middle-aged individuals with high BMI frequently need surgery to detach and reconnect the tendon owing to mucoid degradation of the tendon, which causes steadily worsening discomfort.

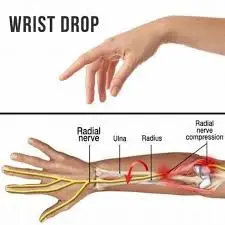

- Pain and diminished feeling across the posterior lateral ankle are symptoms of lumbar (S1) radiculopathy.

Prognosis

Early and appropriate therapy improves the prognosis for Achilles tendinopathy. In the majority of instances, surgical surgery for Achilles tendinosis of insertion (TAI) has a success rate of over 80%. A research by Stenson et al. found that the more risk factors there are, the higher the chance of nonoperative therapy failure.

Higher visual analog scale scores, restricted ankle range of motion, prior corticosteroid injections, and Achilles tendon enthesophytes were among the factors linked to a 55% chance of conservative therapy failure. As a result, in the right clinical context, these risk variables can help surgeons determine whether surgical intervention is necessary.

According to a retrospective research by Sanalla and associates, bone-tendon autografts were a reliable technique with a minimal risk of problems for strengthening the Achilles tendon.

Complications

In surgical therapies for Achilles tendinopathy, the incidence varies from 3% to 41% when severe and mild complications are taken into account. Furthermore, a research by Lohrer et al. found that patient satisfaction rates were similar and that there was no difference in the success rates of open and minimally invasive surgical therapy (83.4%).

On the other hand, the less invasive treatments had decreased incidence of complications. Baltes and his associates categorized surgical treatment-related problems as follows:

- Major side effects include deep vein thrombosis (DVT), reflex dystrophy, deep infections, deep suture responses, tendon avulsion or rupture, any reoperation, and significant wound issues.

- Minor side effects include pain, moderate paraesthesia, minor wound issues, scar sensitivity, hypertrophy, and extended hospital stays.

Whether surgery is done for insertional or non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy also affects the incidence of complications. The percentage of problems after insertional Achilles tendinopathy operations can be as high as 41%, whereas the rate of complications following non-insertional Achilles tendinopathy procedures can be as high as 85%.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

A period of immobilization is necessary after surgery for Achilles tendinopathy, and this may entail the use of a posterior splint, walking boot, or cast. Immobilization lasts anywhere from three to eight weeks. Nonetheless, the number of publications supporting rapid weight-bearing postoperative rehabilitation methods has increased recently.

Protocol for Postoperative Care

- Weeks 0–2: Immobilization in a cast or splint in the equinus position during non-weight bearing (NWB)

- Weeks 2-4: Use axillary crutches in the CAM boot with a 3-layer heel lift (2.4 cm) to transition to 25% partial weight bearing.

- Weeks 4-6: Use a 1.6 cm heel lift and axillary crutches to increase partial weight bearing to 50%.

- Weeks 6–8: Use axillary crutches in the CAM boot with a 0.8 cm heel lift to increase partial weight bearing to 75%.

- Weeks 8–10: Using axillary crutches in the CAM boot without a heel lift while carrying full weight.

- Week 10: As tolerated, go to ordinary shoes.

- Weeks 1-2: Immobilization in a cast or splint in the equinus position during the Accelerated Postoperative Weighbearing Protocol Weeks 2-3: Transition to full weight bearing as tolerated in a CAM boot with a 3-layer (2.4 cm) step heel lift

- Weeks 3–4: The same as before, but with a 1.6 cm drop in heel lift

- Weeks 4-5: The same as before, but with a 0.8 cm drop in heel lift

- Weeks 5 and 6: No heel lift and full weight bearing in a CAM boot

- Week 6: As tolerated, go to ordinary shoes.

FAQs

What are 2 indicators of Achilles tendonitis?

Achilles tendonitis manifests as pain in the heel and down the tendon’s length when jogging or walking.

In the morning, the region was painful and stiff.

Achilles tendon pain upon movement or contact.

soreness and swelling in the heel or along the tendon.

rising up on one toe with difficulty.

What is the duration of Achilles tendinitis?

Following the suggested treatment, the majority of patients with Achilles tendinopathy have an improvement in their symptoms within six months; however, for some, it may take up to a year. During your recuperation, it’s also common to experience flare-ups or times of heightened discomfort.

Can tendons recover on their own?

While rest, ice, compression, and elevation can help many minor tendon injuries recover on their own, more involved care, including surgery, may be necessary for severe or chronic tendon injuries.

Does Achilles tendinitis respond well to heat?

For persistent tendon discomfort, also known as tendinopathy or tendinosis, heat may be more beneficial. Increased blood flow from heat may aid in tendon healing. Because heat relaxes muscles, it can help reduce pain.

How may Achilles tendinitis be quickly cured?

The following actions, commonly referred to by the abbreviation R.I.C.E., are examples of self-care strategies:

Get some rest. For a few days, you might have to refrain from exercising or substitute an activity that doesn’t put undue strain on your Achilles tendon, like swimming.

Ice, compression, elevation, etc.

Is tendinitis ever completely healed?

Most tendinitis patients have rather decent prognoses with rest and treatment. Recovering from tendinitis may take a few weeks to many months, depending on the severity of your injury. Wait for your doctor’s approval before beginning your regular exercise regimen.

References:

- Pabón, M. a. M., & Naqvi, U. (2023, August 17). Achilles tendinopathy. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538149/

- Achillis tendinitis , Physiopedia , https://www.physio-pedia.com/Achilles_Tendinopathy

2 Comments