Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

What is a Thoracic Outlet Syndrome?

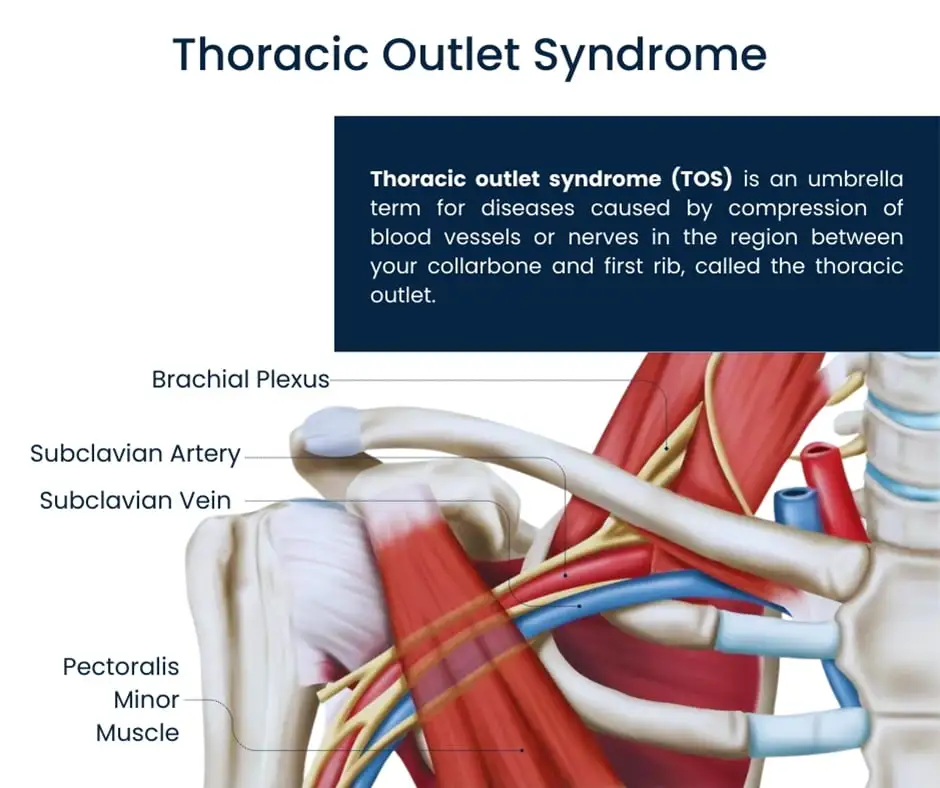

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS) is a condition caused by compression of nerves, arteries, or veins in the thoracic outlet—the space between the collarbone and first rib. It can lead to pain, numbness, tingling, and weakness in the arm and hand.

Common causes include poor posture, repetitive movements, trauma, or anatomical abnormalities. Treatment typically involves physical therapy, posture correction, and in severe cases, surgery.

Thoracic outlet syndrome is frequently caused by pregnancy, repetitive injuries sustained in sports or at work, and damage from auto accidents. An additional or uneven rib is one example of an anatomical difference that might result in TOS. Thoracic outlet syndrome can occasionally have an unknown origin.

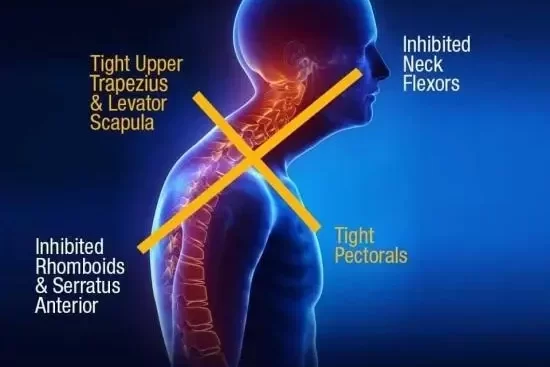

When thoracic outlet pressures rise to the point that they impinge on arteries or nerves, the condition known as thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) occurs. Several structural anomalies, including the thoracic ribs or space-occupying lesions, such as tumors or cysts, can cause these pressures. In anatomically normal people, fibrous bands from overuse or in muscular athletes might result in high pressures. One of the main reasons of TOS symptoms is thought to be past trauma and neck posture, which is a rather simple explanation.

Physical therapy and pain management are common components of treatment. With these treatments, the majority of patients get better. Surgery might be advised for certain people.

Patients may potentially develop TOS as a result of secondary factors. The shoulder may depress if a patient has a deficiency in the trapezius muscle, which may result in a reduction of the outflow and an increase in pressure.

Relevant Anatomy

The interscalene triangle is the name of the initial, closest narrowing area: The medial surface of the first rib inferiorly, the middle scalene muscle posteriorly, and the anterior scalene muscle anteriorly enclose this triangle.

A limited gap and consequent compression may result from the scalene minimus muscle’s presence as well as the anterior and middle scalene muscles’ insertion in the first rib, which may induce overlap. The subclavian artery and the brachial plexus travel via this area.

The second passageway is known as the costoclavicular triangle, and it is bounded by the top border of the scapula on the posterolateral side, the first rib on the posteromedial side, and the middle third of the clavicle on the anterior side. This costoclavicular area is crossed by the subclavian vein, artery, and plexus brachialis, which subsequently enter the subcoracoid space. The interscalene triangle is only distal to it. Congenital anomalies, clavicle or first rib injuries, and structural changes in the subclavian muscle or costocoracoid ligament can all cause compression of these structures.

The subcoracoid or sub-pectoralis minor gap is the final passageway: This final channel is located directly behind the pectoralis minor tendon, beneath the coracoid process. The ribs 2-4 posteriorly, the pectoralis minor anteriorly, and the coracoid process superiorly form the boundaries of the thoraco-cora-copectoral area. This final gap may reduce if the Pectoralis Major is shortened, which would compress the neurovascular structures during hyperabduction.

The thoracic outflow may also be compromised by specific anatomical defects. Congenital soft tissue defects, clavicular hypomobility, the presence of a cervical rib, and functionally acquired anatomical alterations are a few of these.

The neurovascular structures located in the thoracic outlet may be compressed or subjected to tension loading due to soft tissue anomalies (e.g., hypertrophy, a wider middle scalene attachment on the first rib, or fibrous bands that add rigidity.

Epidemiology

About 8% of people have TOS, which is three to four times more common in women than in men between the ages of 20 and 50. Because of their larger breasts, females have less developed muscles, a narrowed thoracic outlet, an anatomical lower sternum, and a greater propensity for sagging shoulders. These factors produce a higher frequency in women by altering the angle between the scalene muscles.

People with TOS are mostly between the ages of 30 and 40; children are rarely affected. The brachial plexus is affected in 95–98% of TOS cases; the remaining 2–5% damage vascular structures such as the subclavian vein and artery.

Baseball and football players, swimmers, divers, and weightlifters are among the athletes who regularly do overhead exercises and subject their subclavian vessels and brachial plexuses to recurrent stress. Numerous consequences, including as brachial plexopathy, arterial occlusions, and venous effort thrombosis, can result from this repeated trauma.

This group is more susceptible to Paget-Schroetter syndrome, which is another name for effort thrombosis. But in every group, neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome continues to be the condition’s predominant symptom.

Pathophysiology

Theoretically, thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) has a simple cause. It appears as a result of several thoracic outlet structures being compressed. This high pressure in the area is probably caused by anatomic anomalies. One of the most frequent causes of thoracic outlet syndrome is cervical ribs, or additional ribs that usually originate from the seventh cervical vertebrae. Cervical ribs were involved in 85% of the 47 neuro TOS procedures involving abnormal ribs that were reviewed. Eighty percent of all cases of neuro TOS were preceded by neck trauma, which led researchers to conclude that the anatomic variation was predominantly responsible for the remaining twenty percent.

Additionally, a case with bilateral TOS was recorded in which the patient had bilateral cervical ribs, leading the doctors to believe that the anatomic anomaly was the major reason. Another important cause of TOS is soft tissue components. TOS can be caused by fibrous muscle bands. The symptoms of TOS can also be caused by tumors or cysts in the thoracic outlet, which raise pressure.

Certain sportsmen, such as elite swimmers, who perform repetitive maneuvers involving severe abduction and external rotation may exhibit symptoms of thoracic outlet syndrome. A swimmer’s complaint of neck or shoulder pain, tightness, or numbness when their hand goes into the water is a classic presentation. Tennis, baseball, and water polo athletes are also frequently prone to this repetitive motion.

Types of thoracic outlet syndrome

- Neurogenic TOS. When the brachial plexus, which connects the neck to the arm, is compressed, neurogenic TOS results. Neurogenic instances account for over 90% of all cases.

- Venous TOS., which results in upper body thrombosis, happens when a vein is compressed. Venous cases account for 5 percent of patients.

- Arterial TOS. When an artery is compressed, arterial TOS happens. Approximately 1% of cases are arterial.

Vascular thoracic outlet syndrome can occasionally be used to refer to both the venous and arterial syndromes.

Causes

Compression of the blood vessels or nerves in the thoracic outlet, which is the region between the neck and shoulder, is frequently the cause of thoracic outlet syndrome.

There are several possible causes for the compression, including:

- Having an extra rib from birth, called a cervical rib.

- Poor posture

- Having large breasts

- A chest, neck, or rib injury (for example, after a vehicle accident)

- Jobs or activities that involve lots of repetitive arm movements (for example, if you’re a builder or do lots of swimming)

- Gaining a lot of muscle (for example, if you’re a body builder)

Difference in anatomy. Some people have an additional rib above the first rib in their neck from birth. Cervical ribs are extra ribs that may restrict blood vessels or nerves. Additionally, there might be a limited fibrous band that compresses the ribs and connects the spine.

Poor posture. The thoracic outlet region may become compressed if you depress your shoulders or hold your head forward.

Trauma. Internal changes caused by a stressful incident, like an automobile accident, might compress the thoracic outlet nerves. Symptoms of a severe injury frequently take time to manifest.

Abnormal muscle or first rib formation: which is an inner neck muscle, or an atypical first rib or clavicle (collarbone) may be present in certain individuals. Nerves or blood arteries may be compressed by any of these abnormal forms.

The cervical rib, that protrudes from the cervical spine, which is the portion of the spine that surrounds the neck, is called a cervical rib. Cervical ribs can grow on one or both sides, stretch down to join the first rib, or not form at all. They are present in 1–3% of the population. The likelihood of nerve or blood vessel compression between the rib and its muscles and ligamentous connections sharing this tiny space is increased if the rib is cervical. Thoracic outlet syndrome is a rare condition that affects a tiny fraction of patients with cervical ribs. Because the bone is generally small and invisible, even on X-rays, many persons with cervical ribs are conscious that they have one.

Thoracic outlet syndrome can result from the following circumstances, particularly in those who have the mentioned neck muscle or bone abnormalities:

- Whiplash: Thoracic outlet syndrome may be indicated by hand and arm pain that lasts for a long time following a whiplash injury.

- Bodybuilding: Excessive growth of neck muscles might crush subclavian veins or nerves.

- Repeated overhead motions: Individuals who play baseball, paint, swim, or work as hairdressers, auto mechanics, or in other occupations requiring lifted arms may experience thoracic outlet syndrome.

- Weight gain: Similar to increased muscle mass, excess neck fat might compress subclavian arteries or nerves.

Symptoms

Thoracic outlet syndrome comes in three varieties:

- Neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome. The most prevalent kind of thoracic outlet syndrome is this one. This kind involves compression of the brachial plexus, a bundle of nerves. The spinal cord supplies the brachial plexus’s nerves. In the hand, arm, and shoulder, the nerves regulate sensation and muscle contraction.

- Venous thoracic outlet syndrome. When one or more of the veins beneath the collarbone are compressed and injured, thoracic outlet syndrome of this kind develops. Blood clots may arise from this.

- Arterial thoracic outlet syndrome. The least prevalent kind of TOS is this one. It happens when there is compression of one of the arteries beneath the collarbone. The artery may be damaged by the compression, leading to the development of a blood clot or a bulge called an aneurysm.

Depending on the type, thoracic outlet syndrome can present with different symptoms. When nerves are compressed, neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome causes the following symptoms:

- Tingling or numbness in the fingers or arm.

- Aches or pain in the hand, arm, shoulder, or neck.

- Arm fatigue with activity.

- A weakening grip.

- It is extremely uncommon for the pad of the thumb, the palm muscle that leads to the thumb, to atrophy, or weaken.

Venous thoracic outlet syndrome symptoms can include:

- Soreness and swelling in the hands or arms.

- Edema, or swelling, in the fingers, hand, or arm

- A bluish discoloration in the hands and arms

- Painful tingling in the hand and arm

- Extremely noticeable veins in the hand, neck, and shoulder

Arterial thoracic outlet syndrome symptoms can include:

- A lump that pulses at the clavicle.

- Cold hands, arms, or fingers.

- Cold and pale hand

- Hand and arm pain, particularly while moving the arm overhead

- Blockage or embolism of an artery in the hand or arm

- Aneurysm of the subclavian artery

- A shift in color throughout the hand or in one or more fingers.

- The affected arm’s pulse is weak or nonexistent.

Diagnoses

- When diagnosing individuals with suspected TOS, nerve conduction tests and electromyography are frequently useful tools. Studies of nerve conduction typically show normal or nearly normal ulnar motor and median sensorial potentials, as well as decreased ulnar sensorial potentials and decreased median action potentials. The use of venography and arteriography can detect vascular TOS.

- Imaging studies can offer valuable information in the diagnosis of TOS in addition to electrophysiological testing. X-rays of the chest and cervical spine are crucial for detecting bone anomalies, such as “peaked C7 transverse processes” or cervical ribs.

- Movements or physical actions that elicit symptoms. Examine via history to rule out nerve-related illnesses that may be mistaken for thoracic outlet syndrome, such as cubital tunnel syndrome, carpal tunnel syndrome, cervical spine disease, or other forms of nerve entrapment. To rule them out, investigations like cervical spine MRIs or nerve conduction studies may be required.

Additional diagnostic tests that are commonly requested to help with diagnosis:

- Duplex ultrasonography to detect blood vessel occlusion (blockage) or stenosis (narrowing)

- Chest X-ray of the chest to look for anomalous first ribs or cervical ribs

If neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome is suspected:

- Brachial plexus block: The neck’s scalene muscles get an injection of a local anesthetic. If this area is numb and other symptoms go away, the likelihood of neurogenic TOS increases.

Special Tests

Elevated Arm Stress/ Roos test

One diagnostic method for determining Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS) is this test.

- Both arms are in the 90° abduction-external rotation posture on the patient.

- The frontal plane of the chest contains the elbows and shoulders.

- For three minutes, the patient is to slowly open and close their hands.

Possible symptoms if TOS is present:

- Progressively worsening shoulder and neck ache that travels down the arm

- Paresthesia in the fingers and forearm

- Arm pallor with an elevated arm and response hyperemia when the limb is lowered are signs of artery compression.

- Cyanosis and edema in venous compression cases

- Reproduction of typical symptoms is evident when the patient is unable to finish the test and drops their arms in their lap in obvious distress.

Adson test

The provocative Adson’s test can be used to detect thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS). It includes holding a deep breath while moving the head to the symptomatic side and stretching the neck. The test looks for a radial pulse loss or symptom reproduction.

Procedure

- The test can be administered to the patient sitting or standing with their elbow completely extended.

- Whether the patient is sitting or standing, their arm is maximally extended and abducted 30 degrees at the shoulder.

- The examiner takes hold of the patient’s wrist and palpates the radial pulse.

- After that, the patient is told to move their head toward the affected shoulder, lengthen their neck, and take a deep breath and hold it.

- The radial pulse’s quality is assessed by contrasting it with the pulse obtained at the patient’s side while the arm is at rest.

- In a modified test, some clinicians ask patients to move their head away from the side being evaluated.

If the radial pulse significantly diminishes or vanishes, the test is positive. It’s crucial to examine the radial pulse on the other arm to determine the patient’s normal pulse. It is important to compare a positive test result with the non-symptomatic side.

Cyriax Release

The patient must be seated to administer the test. While keeping the hands, wrists, and forearms in a neutral position, the therapist stands behind the patient and grasps beneath the forearms to hold the elbows at an angle of about 80 to 90 degrees. The therapist next raises the patient’s shoulder girdle near end range and leans the patient’s trunk posteriorly, about 15° from vertical. For a maximum of three minutes, both shoulder girdles are maintained in this passive elevation position.

If a release phenomenon happens or the patient’s well-known symptoms are replicated, the test is deemed positive.

Supraclavicular pressure

The patient sits with their arms at their sides to apply supraclavicular pressure. The examiner positions his thumb on the anterior scalene muscle close to the first rib and his fingers on the upper trapezius. The examiner then applies a 30-second pressure to the thumb and fingers. Scalene triangles are used to address brachial plexus compromise if the test results show a reproduction of pain or paresthesia.

Costoclavicular maneuver

The costoclavicular maneuver is a technique that can be performed to assess vascular and neurological impairment. The patient hyperflexes his chin and brings his shoulders posteriorly. A reduction in symptoms indicates that the neurogenic component of the neurovascular bundle is compressed and the test is positive.

Differential Diagnosis

Many traumas and nonspecific pain conditions are prominent differentials for thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) because of the ambiguous nature of its symptoms. Pectoralis minor syndrome is one condition that is frequently confused. In addition to causing pain in the anterior chest wall, trapezius muscle, and over the scapula, pectoralis minor syndrome (PMS) can also cause paresthesia or pain in the hands and arms. The pectoralis minor muscle, not the thoracic outlet, compresses nerves, causing PMS.

Other Differentials Include:

- Brachial plexus injuries

- Cervical spine injuries

- Cervical radiculopathy

- Shoulder impingement syndrome

- Elbow or forearm overuse injuries

- Acromioclavicular joint injury

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- De Quervain’s tenosynovitis

- Lateral epicondylitis

- Medial epicondylitis

- Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).

- Horner’s Syndrome

- Raynaud’s disease

- Systemic conditions include heart, esophageal, or inflammatory diseases.

- Upper extremity deep venous thrombosis (UEDVT); thrombosis

- Rotator cuff injury

- Glenohumeral joint instability

- Nerve root involvement

- Shoulder Instability

- Malignancies (local tumors)

- Chest pain, angina

- Vasculitis

- Thoracic (T4) syndrome

- Sympathetically induced pain.

Treatment

Medical treatment

- To lessen pain and inflammation, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications have been recommended.

- Although it has also been discovered that botulinum injections to the anterior and middle scalene can momentarily lessen pain and spasm caused by neurovascular compression, more research is required due to inconsistencies in the literature.

Physical Therapy treatment

The first line of treatment for TOS should be conservative management since it appears to be successful in reducing symptoms, promoting return to work, and enhancing function. However, some studies have assessed the best exercise regimen and the distinction between conservative management and no treatment.

Physical therapy, which is a component of conservative management, emphasizes patient education, pain management, range of motion, nerve gliding techniques, strengthening, and stretching.

Stage 1

Reducing the patient’s symptoms is the goal of the first phase. Patient education that explains TOS, poor posture, the prognosis, and the significance of therapy compliance may help achieve this. Additionally, to prevent nighttime awakenings, certain patients who sleep with their arms in an abducted, above position should learn more about their sleeping habits. It is recommended that these patients sleep supine or on their unaffected side, possibly with their sleeves pinned down. If there is a “release phenomenon,” the Cyriax release test may be applied. Before retiring to bed, this method fully unloads the neurovascular systems in the thoracic outlet.

Cyriax Release Maneuver

- 90° flexed elbows

- A passive shoulder girdle elevation is produced by towels.

- Neutrally supported head and spine

- Until peripheral symptoms appear, the position is maintained. The patient is advised to suffer symptoms for as long as possible, up to half an hour, while monitoring for a decline in symptoms over time.

- Since the scalene and other auxiliary muscles frequently compensate to raise the rib cage during inspiration, the patient’s breathing methods need to be assessed. Promoting diaphragmatic breathing can potentially alleviate symptoms by reducing the strain on already overworked or constricted scalene.

Scapula Settings and Control

Setting and controlling the scapula is the first step in the treatment. Establishing proper scapula muscle recruitment and control while at rest depends on this. After this is accomplished, the training moves on to scapula control maintenance under load and motion. Before muscles are being retrained in functional movement patterns at greater elevations, the program starts in lower abduction ranges and progressively advances into abduction and flexion ranges.

Control the Humeral Head Position

Controlling the location of the humeral head is also crucial. Particular exercises are provided to help with humeral head control. An increase in the humeral head’s anterior location is the most prevalent abnormal position. Facilitating a mid-level isometric contraction of the rotator cuff by applying resistance on the humeral head is a helpful technique to help encourage co-contraction of the rotator cuff to help stabilize and center the humeral head.

This could be included into movement patterns later on in the course of treatment. Drills for isolated muscle strengthening were performed after slow, controlled concentric/eccentric motion exercises.

Serratus Anterior Recruitment and Control

The above-discussed abduction external rotation techniques are frequently adequate to initiate serratus anterior activation and control without running the risk of over-activating the pectoral minor muscle.

Stage 2

The patient might proceed to this phase of treatment once they can manage their symptoms. Directly addressing the tissues that provide structural restrictions of mobility and compression is the aim of this stage. One of the most talked-about aspects of this condition is how this should be done. The following are some instances of techniques that are employed in the literature.

- Massage

- Strengthening of the levator scapulae, sternocleidomastoid and upper trapezius (This group of muscles open the thoracic outlet by raising the shoulder girdle and opening the costoclavicular space)

- Stretching the muscles that shut the thoracic outlet, the pectoralis, lower trapezius, and scalene.

- Postural correction exercises

- Relaxation of shortened muscles

- Aerobic workouts as part of a daily routine at home

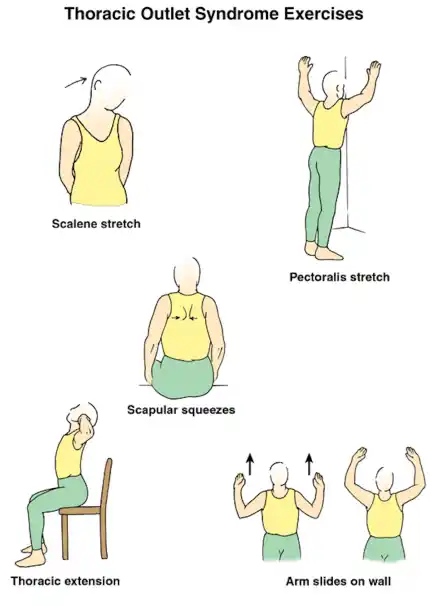

Exercises

- Workouts for the shoulders to increase range of motion and provide the neurovascular structures more room.

- Flex your upper thoracic spine, raise your shoulders back and up, and then lower and raise them. After that, straighten your back and do it five to ten times.

Upper cervical spine range of motion.

- Exercise: While standing with the back of your head against a wall, lower your chin five to ten times against your chest. Pressing the head down with the hands increases the exercise’s effectiveness.

- The most crucial exercises are those that activate the scalene muscles. These exercises aid in restoring the thoracic aperture’s natural function as well as any first rib dysfunctions. Anterior scalene exercises involve pressing your forehead five times on your palm for five seconds without moving, middle scalene exercises involve pressing your head sideways against your palm, and posterior scalene exercises involve pressing your head backwards against your palm.

- Stretching activities

Manipulative Treatment to Mobilize the First Rib

These should only be performed cautiously and following a comprehensive evaluation because they may cause some individuals to experience pain and irritation.

- Arm Flexion and Posterior Glenohumeral Glide: The patient is in a supine position. Avoiding the coracoid process, the mobilization hand makes contact with the proximal humerus. The force is applied in the thumb’s posterolateral direction.

- Arm Scaption and Anterior Glenohumeral Glide: The patient is in a prone position. Avoiding the acromion process, the mobilization hand makes contact with the proximal humerus. Anteromedially is the direction of the force.

- Posterior Glenohumeral Glide with Arm Flexion: Patient supine. Mobilizing hand contacts proximal humerus avoiding coracoid process. Posterolateral force is applied (thumb direction).

- Anterior Glenohumeral Glide with Arm Scaption: Patient prone. Avoiding the acromion process, the mobilizing hand makes contact with the proximal humerus. Anteromedially is the force.

- Inferior Glenohumeral Glide: Patient prone. Stabilizing hand holds proximal humerus. Mobilizing hand contacts the axillary border of the scapula. Move the scapula along the rib cage in a craniomedial orientation.

- The patient is prone when they have an inferior glenohumeral glide. The proximal and distal humerus to the lateral acromion process are held in place by the stabilizing hand. The mobilizing hand makes contact with the scapula’s axillary border. Move the scapula along the rib cage in a craniomedial orientation.

- The patient sits for the first rib mobilization. The first rib is surrounded by a thin sheet of tissue. Pull the strap in the direction of the other hip. Ipsilateral rotation, contralateral lateral flexion, and neck retraction. Scalene stretch is emphasized by ipsilateral head rotation. Rib mobilization is emphasized by contralateral rotation.

Surgical treatment

Only after conservative treatment has failed can surgery be considered for the management of TOS. However, surgical intervention has been indicated for limb-threatening complications of vascular TOS.

A trans axillary, supraclavicular, or infraclavicular approach are among the various surgical techniques that can be used to treat thoracic outlet syndrome.

Trans axillary approach.

Removing the first rib usually alleviates symptoms because it is the common denominator for all instances of nerve and artery compression in this area. Without affecting the blood arteries or nerves, the surgeon makes an incision in the chest to reach the first rib, splits the muscles in front of it, and removes a section of it to relieve compression.

Supraclavicular approach

Scalenectomy, a safe and efficient treatment with a shorter operating time and a complication rate lower or comparable to trans axillary first rib resection, has been recommended in conjunction with first rib resection. Compressed blood vessels are repaired using this method. The brachial plexus region is exposed by the surgeon making an incision directly beneath the neck. He then searches for indications of injury or muscles that are causing compression close to the first rib. If necessary, the first rib may be removed to relieve compression.

Infraclavicular approach.

Using this method, the surgeon cuts across the chest and beneath the collarbone. Compressed veins that need considerable repair may be treated with this treatment.

Neurogenic TOS

For those who exhibit genuine neurological signs or symptoms, surgical decompression should be taken into consideration. These include conduction velocity less than 60 m/sec, weakness, and atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand. One of the main causes of TOS may be the first rib. However, there is disagreement about whether a full resection is required to lower the risk of scalene reattachment, scar tissue formation, or bone growth of the residual tissue. This includes excising fibrous bands, performing scalenectomies, and removing cervical ribs in addition to the first rib. Terzis discovered that the supraclavicular way of treatment was a precise and successful surgical technique.

Arterial TOS

Revision of the scalene muscles and removal of the cervical and/or first ribs are examples of decompression. After that, the subclavian can be examined for aneurysm, dilatation, or degeneration. If required, a synthetic prosthesis or saphenous vein transplant can then be utilized.

Venous TOS

For these patients, thrombolytic therapy is the initial course of treatment. Even when thrombolytic therapy fully opens the vein, many advise that the first rib be removed due to the possibility of recurrence. The infraclavicular technique is a safe and effective treatment for acute VTOS, according to study results. They were free of phrenic nerve and brachial plexus damage. Those with venous stenosis can then be treated with angioplasty.

Before thoracic outlet compression in venous or arterial TOS, medicines can be given to break up blood clots. Before thoracic outlet decompression, a procedure to remove a clot from the vein or artery or to repair the vein or artery may also be required.

The sagging shoulders of some women with bigger chests put more strain on the neurovascular structures in the thoracic outlet. Tension can be lessened with a supportive bra that has wide, posterior-crossing straps. In severe situations, breast reduction surgery may be necessary to alleviate TOS and other biomechanical issues.

Risk factors

The following are some factors that appear to raise the risk of thoracic outlet syndrome:

- Sex. The diagnosis of thoracic outlet syndrome is more than three times as common in women than in men.

- Age. Although it can happen at any age, adults between the ages of 20 and 50 are the most likely to be diagnosed with thoracic outlet syndrome.

Prevention

Avoid heavy lifting and repetitive motions if you have thoracic outlet compression. If you are overweight, you may be able to avoid or alleviate thoracic outlet syndrome symptoms by losing weight.

Carrying large bags over your shoulder is not recommended, even if you do not exhibit signs of thoracic outlet syndrome. The thoracic outlet may experience increased pressure as a result. Every day, stretch and perform exercises that maintain the strength and flexibility of your shoulder muscles. Shoulder muscular strength can be increased and thoracic outlet syndrome can be avoided with daily stretches that target the shoulders, neck, and chest.

Complications

The kind of thoracic outlet syndrome is the cause of its complications. It’s critical to get medical help right away if your arm is swollen or painfully discolored. Aneurysms or blood clots may require therapy.

Repetitive nerve compression in neurogenic TOS can cause long-term damage that leads to persistent pain or disability. Other joint or muscle injuries can be mistaken for neurogenic TOS. It’s critical to get medical help for an assessment and testing if symptoms don’t get better. TOS does not correspond with high rates of problems because the illness is subtle and most treatment approaches are benign. A vascular compromise may result in ischemic change. In extreme situations, venous gangrene and possibly even phlegmasia cerulea dolens may develop.

The majority of doctors advise conservative therapy because surgical intervention is the primary cause of most problems. One of the most feared side effects of surgery for TOS is iatrogenic nerve damage. Resection of the first rib may cause pneumothorax. Although they are much less frequent, bleeding problems can still occur after surgery.

- Muscle weakness caused by injury to the blood vessels or nerves

- Lung collapse

- Failure to relieve the symptoms

Prognosis

In general, people with thoracic outlet syndrome have a very good prognosis. In over 90% of cases, patients who get conservative therapy experience a resolution in their symptoms. As long as their injury was not caused by repetitive motions, where lifestyle changes would be necessary, the majority of these people do not relapse. To get the best outcomes, they should limit their exposure to activities that need their arms to be raised for prolonged periods.

Conclusion

Compression of neurovascular systems in the thoracic outlet is a difficult problem associated with thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS). It necessitates a thorough diagnostic and treatment plan that includes both conservative and surgical measures. With an emphasis on patient education, posture correction, strengthening, and stretching exercises, physical therapy is essential to symptom management and rehabilitation.

When surgery is required, the goal is to relieve compression and regain function. Physical therapy following surgery is crucial for maximizing healing and averting problems. To improve our knowledge and care of this illness, multidisciplinary cooperation and ongoing study are essential.

FAQs

What signs of thoracic outlet syndrome are present?

Pain, tingling, or weakness in the arm and shoulder are some of the symptoms, particularly when elevating the arms. Thoracic outlet syndrome is more likely to occur if you have a cervical rib, which is an additional rib that protrudes from the neck. Treatments for thoracic outlet syndrome vary depending on its type.

How is thoracic outlet syndrome treated by a physical therapist?

To determine which structures are affected and how they are being compressed, a physical therapist will start with a thorough evaluation. Typically, treatment consists of: Exercises for Posture Correction: By increasing the thoracic outlet space and improving posture, these exercises help to lessen the strain on the structures.

How can thoracic outlet syndrome affect sleep?

Positions for Sleeping: Avoid sleeping on the side that is impacted! Although it’s best to lie on your back, it’s also acceptable to lie on the side that isn’t affected and place a pillow between your arms to prevent your shoulders from rounding.

Which three forms of thoracic outlet syndrome exist?

In particular, an artery, a vein, and a nerve plexus are the three main structures that go through each thoracic outlet. Therefore, venous thoracic outlet syndrome, neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome, and arterial thoracic outlet syndrome are the three categories of thoracic outlet syndrome.

Is the thoracic outlet permanent?

Is the thoracic outlet syndrome going to disappear? The symptoms of TOS may resolve on their own or with nonsurgical treatments, depending on the underlying etiology. However, you should consult your doctor if your symptoms are intermittent or do not improve. Some forms of TOS cannot be cured without surgery or minimally invasive treatment.

Which pain reliever works best for thoracic outlet syndrome?

NSAIDs, or over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, can help ease the pain and inflammation caused by compressed nerves. Ibuprofen and naproxen are common NSAIDs.

Which hospital is the best for thoracic outlet syndrome?

Over 1,200 patients with thoracic outlet syndrome receive thorough care each year from the medical staff at the Mayo Clinic. Surgical proficiency. Thoracic outlet syndrome can be treated with physical therapy, medications, and surgery, according to Mayo Clinic specialists.

For thoracic outlet syndrome, which workouts are beneficial?

Exercises for Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: Advice from TOS Professionals

Generally speaking, TOS rehabilitation exercises could concentrate on increasing the flexibility of the affected joints and strengthening the muscles surrounding the shoulder girdle. Shoulder shrugs, scapular retractions, external rotations using dumbbells or resistance bands, and stretches for tense chest muscles are a few possible exercises.

Can breathing be affected by TOS?

Patients with TOS and healthy controls had identical pulmonary function metrics (P >.05), except peak expiratory flow rate. When compared to controls, patients with TOS had noticeably reduced respiratory muscle endurance, MIP, MIP%, MEP, MEP%, and peak expiratory flow rate.

How is thoracic outlet syndrome tested for?

Doppler and traditional ultrasonography are combined in the arterial duplex ultrasound test. Doppler ultrasonography creates color images of the body by using sound waves. This test may be used by your physician to evaluate blood flow in the thoracic exit arteries. This aids the physician in locating any obstructions or compressions.

Does TOS last forever?

Untreated TOS can result in blood clots and other severe problems, including irreversible nerve damage. Seeking attention is crucial if you are at risk or exhibiting any of the symptoms.

Reference

- Thoracic outlet syndrome – Symptoms and causes. (n.d.). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/thoracic-outlet-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20353988

- Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. (2024, May 24). Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/thoracic-outlet-syndrome

- Website, N. (2024a, January 4). Thoracic outlet syndrome. Nhs.uk. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/thoracic-outlet-syndrome/

- National Library of Medicine. (n.d.). Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. TOS | MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/thoracicoutletsyndrome.html

- Thoracic outlet syndrome: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. (n.d.). https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001434.html

- Physiotutors. (2022, July 28). Cyriax Release Test | Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Assessment. https://www.physiotutors.com/wiki/cyriax-release-test/