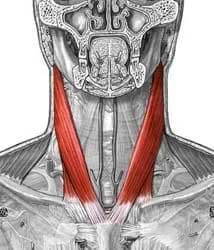

Sternocleidomastoid Muscle

The sternocleidomastoid muscle, often abbreviated as SCM, is a prominent muscle located in the neck. Its name is derived from its points of origin and insertion: the sternum (sterno-), clavicle (cleido-), and mastoid process of the temporal bone (mastoid). This large, superficial muscle plays a crucial role in various head movements, including rotation, flexion, and lateral flexion of the neck.

What Are The Sternocleidomastoid Muscle?

The anterior line of the neck has a pair of superficial muscles called the sternocleidomastoid (SCM), also known as the musculus sternocleidomastoideus. An essential marker in the neck that separates it into an anterior and a posterior triangle is the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM). It guards against harm to the cervical plexus branches, deep cervical lymph nodes, vertical neurovascular bundle, and neck soft tissues.

More than 20 pairs of muscles work on the neck, including the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM). The SCM performs a variety of tasks and has two innervations. It is a muscle that can be felt on the surface and is a significant anatomical landmark in the neck region and a component of neuromuscular disorders like torticollis.

Beyond its primary role as a lateral neck flexor, electrophysiological investigations provide evidence that the SCM collaborates with the entire cervicofacial muscle group, responding to and supporting a variety of complex physiological motions.

The first of the biggest and most visible cervical muscles is the sternocleidomastoid. Flexion of the neck and head rotation to the other side are the main functions of the muscle. The accessory nerve innervates the sternocleidomastoid.

Structure of Sternocleidomastoid Muscle

The anterior and posterior triangles of the neck are separated by the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM). The posterior border of the SCM, the inferior border of the mandible inferiorly, and the medial line of the neck medially define the anterior triangle.

The muscles of the suprahyoid and infrahyoid are located in the anterior triangle. The SCM on the anterior side, the clavicle on the inferior side, and the trapezius muscle on the posterior side define the posterior triangle. The posterior triangle is home to the scalene muscles. The SCM is a sizable, palpably felt muscle that is easy to identify.

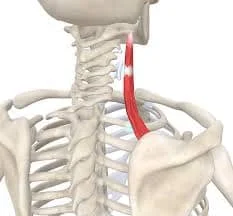

The muscle begins at the medial part of the clavicle’s top face and the sternal manubrium’s upper border. The two heads of the muscle combine to form a single, laterally and upward-directed muscle belly. Insertions land on the anterior part of the superior nuchal line and at the temporal bone’s mastoid process. SCM is not a pennate muscle; instead, its fibers are organized in parallel.

Due to its two sites of origin (clavicle and sternum) and two sites of attachment (occiput and mastoid process), the SCM can be divided into four sections: cleidomastoid, cleido-occipital, sterno-occipital, and sternomastoid.

The muscle part in the SCM that can develop a higher percentage of contractile strength during muscle activity is the sternomastoid component. On the other hand, the muscle area with the least amount of force development is the cleido-occipital part.

There are two places where the sternocleidomastoid muscle starts: the clavicle and the manubrium of the sternum. Through a narrow aponeurosis, it inserts at the mastoid process of the temporal bone of the skull after traveling obliquely across the side of the neck. The center of the sternocleidomastoid is thick and narrow, while the ends are larger and thinner.

The upper portion of the front of the manubrium sterni gives rise to the circular fasciculus known as the sternal head, which is fatty behind and tendinous in front. It moves laterally, posteriorly, and superiorly.

The medial third of the clavicle’s top frontal surface gives rise to the clavicular head, which is made up of fatty and aponeurotic fibers and is oriented nearly vertically upward.

The two heads have a triangular interval (the lesser supraclavicular fossa) separating them at the origin. Still, they gradually blend below the middle of the neck to form a thick, rounded muscle that is inserted into the lateral surface of the mastoid process from its apex to its superior border by a strong tendon, and into the lateral half of the occipital bone’s superior nuchal border by thin tendons.

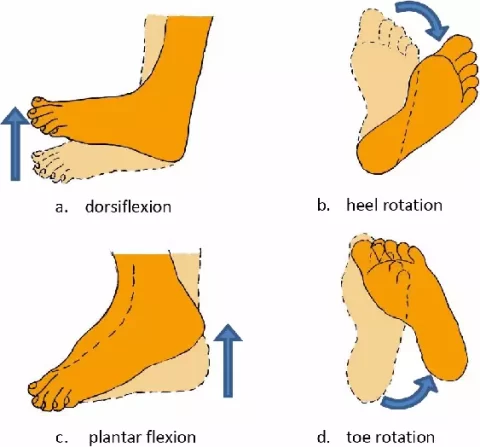

Function of Sternocleidomastoid Muscle

This muscle is responsible for obliquely or to the opposite side rotation of the head. The muscle flexes the neck and extends the head when both sides contract simultaneously. The head rotates to the other side and bends laterally to the same side when one side operates alone.

Along with the neck’s scalene muscles, it functions as an accessory muscle for breathing.

When the SCM contracts unilaterally, three movements are associated: the head rotating on the side opposing the contraction, the head inclining away from the contraction side, and the head extending.

Contraction

The effects of the two muscles contracting simultaneously depends on how the other cervical spine muscles are contracting:

- This bilateral contraction results in a cervical spine hyperlordosis, which extends the head and bends the cervical spine dorsally, if the cervical spine is not stabilized.

- The simultaneous contraction of the SCM dictates the bending of the head forward and the flexion of the cervical spine on the dorsal spine if the paravertebral muscles have contracted, making the cervical spine fixed and linear.

A crucial role of SCM is maintaining proper temporomandibular joint (TMJ) function. A trigeminal-cervical reflex is triggered during chewing and there is evidence that SCM innervation is essential for the best possible TMJ occlusion. The function of the SCM is altered by an occlusal change of the jaw, leading to diseases of muscle incoordination (neck inclinations).

Torticollis has occasionally been resolved by treating a tooth or correcting an occlusion that has changed. The masseter muscle and the SCM contract simultaneously while one side is being bit.

Cranial nerve XI, the accessory nerve, is the starting point for the signaling process to contract or relax the sternocleidomastoid. Lower motor neuron fibers indicate the origin of the accessory nerve nucleus, located in the spinal cord’s anterior horn between C1 and C3. Through the foramen magnum, the fibers from the accessory nerve nucleus ascend to enter the skull. The sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles are both supplied by the internal carotid artery. A signal is transmitted to motor endplates on the muscle fibers at the clavicle after it passes via the accessory nerve nucleus in the anterior horn of the spinal cord.

Released from vesicles, acetylcholine (ACH) travels across the synaptic cleft to attach to receptors on the postsynaptic bulb. An action potential that travels along the muscle fiber is started by the ACH, which raises the resting potential above -55 mV. T-tubule apertures are located along the muscle fibers and help the action potential propagate into the muscle fibers.

At some points along the muscle fiber, the sarcoplasmic reticulum and the t-tubule converge. The sarcoplasmic reticulum releases calcium ions at these sites, which causes troponin and tropomyosin to migrate along thin filaments. The sternocleidomastoid muscle contracts as a result of the myosin head moving along the thin filament, which is facilitated by the movement of troponin and tropomyosin.

Anatomical landmark

The sternocleidomastoid muscle and the trapezius muscle share the same neural supply, known as the accessory nerve, and are located within the investing fascia of the neck. Because it is thick, it acts as a key landmark for the neck, dividing it into anterior and posterior cervical triangles (behind the muscle, respectively), which aid in defining the locations of structures like the head and neck lymph nodes.

The sternocleidomastoid is related to numerous significant structures, such as the brachial plexus, accessory nerve, and common carotid artery.

Origin

It comes from the two heads:

- A tendinous, rounded, medial sternal head (SH)

- A fleshy clavicular head (CH) on the side.

They originate from the medial third of the anterior and posterior surfaces of the manubrium sterni and the superior surface of the clavicle, respectively. The thickness of the CH varies. The smaller supraclavicular fossa, a triangular-shaped surface depression, lies between the two heads. The CH becomes a fat, rounded belly as they ascend, spiraling behind the SH and blending with its deep surface below the middle of the neck.

Insertion

When using aponeurosis to the lateral part of the superior nuchal line and the lateral surface of the mastoid process.

Blood Supply

The branches of the external carotid artery that supply blood to the SCM are the occipital artery and superior thyroid artery, which are palpable with the pulse in the medial-anterior portion of the muscle. The blood flow to the respiratory muscles, including the SCM, rises during vigorous physical exercise, which is detrimental to the limb muscles.

Draining venous blood via the external posterior and anterior jugular veins, the external jugular vein travels inferiorly and posteriorly to the SCM.

Lymphatics

The neck’s lymphatic system drains the SCM through a vertical chain that is comprised of the posterior triangle’s (inferior) lymph nodes and the anterior superficial lymph nodes.

Nerves supply

The anterior and posterior surfaces of the manubrium sterni and the superior surface of the clavicle, respectively. The thickness of the CH varies. The smaller supraclavicular fossa, a triangular-shaped surface depression, lies between the two heads.

Action

The cervical spine flexes and rotates laterally. extends the head when working in balance. when the neck is already half stretched, extend it.

Related Muscles

The myofascial system, which rules both an anatomical and functional continuum, includes the muscles that make up the neck. This suggests that any failure of a single muscle or a section of a muscle will cause all of the neck muscles to behave differently. For example, an eye disease modifies the masseter and neck muscles’ electromyographic spectrum, which includes the SCM.

No matter how deep the muscle layer is, the reticulospinal system allows the cortical system to stimulate the neck muscles, both deep and superficial. This synchronous activation occurs. Therefore, when the disease appears to include only one neck muscle, evaluation of the entire neck muscular complex is necessary.

About 65% of the SCM in healthy individuals is made up mostly of white, or anaerobic, fibers, whereas only about 35% is made up of red, or aerobic, fibers. Over extended periods, the muscle can rapidly generate a great deal of strength with less resistance. As one age, the proportion of white and red fibers in the SCM varies. White fibers often suffer from an approximate 44% increase in red filaments. The muscle adjusts to its changing surroundings and advancing years.

Embryology

The SCM originates from paraxial (pre-optic) mesoderm and occipital (post-optic) somites, and it is mostly produced from neural crests. In animal models, on the fourteenth day of gestation, the SCM develops. According to a new study, progenitor cells of the heart and the cells that will eventually give rise to the muscles of the neck share space within the cardiopharyngeal dermis.

Anatomical Variation

Congenital development of the SCM is an uncommon variation that may not result in any functional or clinical abnormalities. It could also involve the simultaneous atrophy of the trapezius muscle. Most likely, compensatory adjustments made by other neck muscles are the cause of this.

The origin of the SCM is one of its other variations, and it can affect the outcome of a local surgical surgery. The clavicular attachment in the SCM may cause several muscular bellies or affect the acromion-clavicular joint. It may be small or large (up to approximately 7 to 8 cm) or have multiple clavicular attachments. The anatomical anatomy of the neck is known to be altered by insertions into the sternoclavicular joint.

There are many SCM muscle heads, which is unusual. For instance, on one side, there are a total of four muscle heads: one occipital origin, one cleido-occipital origin, one sternomastoid origin, and two cleidomastoid origins.

On rare occasions, the SCM margin—likely due to embryological defects—may come into direct contact with the trapezius. There are variants with one or more heads known as cleido-epistrophic, cleido-cervical, and cleido-atlantic insertions.

The SCM’s innervation can differ. One study claims that the bottom region of the SCM is innervated by the bilateral hypoglossal, a branch of C1 from the ansa cervicalis; this innervation is only Practical for the upper part of the muscle. It has been discovered that an abnormal branch of the facial nerve innervates the deep portion of the upper third of the SCM.

When attempting surgery in this area, keep in mind all of these anatomical considerations and proceed with care.

Surgical Considerations

The sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) can be utilized as an autograft to correct anatomical abnormalities.

When removing a tumor from the parotid gland, a flap of the SCM may be utilized. Because of the high vascularization of SCM, the muscle reduces the danger of necrosis, lessens the depression of the parotidectomy area, and makes it easier to obtain an optimal length and rotation of the flap on the incision area during the intervention. Preventing Frey syndrome (auriculotemporal nerve damage) is not completely safe.

In numerous other circumstances when orofacial and pharyngeal reconstruction or repair is required, SCM is employed. Certain muscle flaps or flaps with bony sections are used, depending on the surgical goal. Reconstructive interventions include, for example:

- Restoration of the buccal floor and tongue

- Laryngotracheal complex, oropharynx, and oral cavity

- Various head and neck parts

- The mandible and abnormalities in the mastoid region

- Complex esophageal-pharyngeal

- reconstruction of the cheek

Congenital muscular torticollis (MT) can also be surgically repaired using SCM muscle flaps. The head and shoulder positions are affected by the shortened and fibrotic SCM in muscle torticollis, resulting in ipsilateral lateral flexion and contralateral facial rotation in the child. Surgery or rehabilitation are the two available forms of treatment.

A pending diagnosis without treatment could cause a shortened SCM and the development of a rigid ring of muscle. When MT is severe, it might continue and result in craniofacial morphological abnormalities. It is still feasible to achieve good outcomes throughout the first five years of life, although it is preferable to act sooner rather than later.

The objective is to release the stiff band of the SCM in cases of untreated congenital stiff neck in adults; the outcome is never comparable to early childhood intervention, but some facial and cervical malformations can improve.

Typically, children and adults experience surgery to remove a portion of the SCM.

Clinical Significance

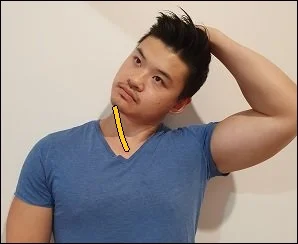

Sternocleidomastoid Muscle Function Evaluation

Diagnose the patient while they are seated to identify any hypotrophy of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) and postural abnormalities of the neck and head, shoulder and scapula, clavicle, and sternal manubrium.

The patient is asked to do some voluntary neck motions to evaluate any motor or discomfort limits.

To evaluate the reflexes at the clavicular insertion of the SCM, a small tendon hammer is utilized.

The patient moves their head in flexion, rotation, and inclination as the examiner applies minimal resistance to observe their level of muscle strength.

The accessory nerve (CN XI) may be affected by SCM lesions, although these are rare. An increase in the depth of the supraclavicular fossa, atrophy of the SCM and trapezius, a lowering of the shoulder, and the absence of the tendon reflex are all symptoms of a CN XI lesion. A type of torticollis can result from paralysis of the SCM.

There are Different Types of Torticollis

- Damage to the cranial nerve XI resulting in paralytic torticollis.

- Other intrauterine packaging abnormalities such as metatarsus adductus, acetabular dysplasia, developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), and congenital hip dislocations are frequently linked to congenital torticollis. About 15% of cases of congenital torticollis are accompanied by metatarsus adductus.

- Segmental dystonia is the cause of spasmodic torticollis.

- Ocular torticollis, in which the SCM’s position is affected by diplopia.

- There are several possible causes of symptomatic torticollis, such as cervical vertebral posture, discomfort, inflammation, or infection.

- Patients with “psychic pillow” torticollis, a symptom sometimes associated with severe neurological conditions like Parkinson’s disease or catatonic disorders, have their heads bent forward even when they are supine as if they were lying on a pillow.

- The hallmark of psychogenic torticollis is a fear of making the proper neck motions because of the start of vertigo or pain.

An electromyographic examination and imaging tests like computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or ultrasound are frequently necessary for specific diagnosis of these illnesses.

Other Issues

Manual Approach: Physiotherapy

One-third of congenital muscle malformations are caused by congenital torticollis, for which physiotherapy is an essential treatment. Stretching exercises, parent-initiated posture corrections, or voluntary posture improvement motions are all examples of recommended conservative therapy. However, the problem is available in many cases. Different techniques for SCM may be used depending on the medical indication and the therapist’s assessment.

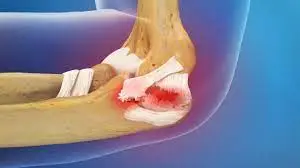

Incorrect chromosome proliferative myositis, fibromatosis colli, sternocleidomastoid rupture, and intramuscular hemangioma are a few of the conditions that may require an initial surgical approach.

According to recent research, individuals with chronic neck pain exhibit higher electrical activity in their SCM than those without such discomfort. People who have cervical pain for an extended period have more fat infiltration in the SCM than people who do not. Combining standard physiotherapy with massage and stretching demonstrates that it is the right choice for patients in this therapeutic context.

In addition, temporomandibular disorders are linked to modifications in the electromyographic spectrum of the SCM. It is possible to confirm the existence of mandibular dysfunctions with this diagnostic procedure.

Osteopathy and Manual Therapy

Scar formation should be reduced in SCM patients receiving osteopathic therapy after surgery. Osteopathic manipulation targets the cervical myofascial layers and the gaps between the cervical vertebrae using soft, imperceptible techniques.

Scar formation should be reduced in SCM patients receiving osteopathic therapy after surgery. Gentle, non-invasive techniques are used in osteopathic manipulation to address the cervical myofascial layers and the spaces between the cervical vertebrae.

Exercises of Sternocleidomastoid Muscle

Sternocleidomastoid Muscle stretching exercise

SCM Stretch

- Stack your fingers on your collarbone on the right side.

- Draw the skin down.

- Put your chin down and inside.

- Rotate your head slowly to the right.

- Lead your head in a leftward direction.

- Try to feel the proper Sternocleidomastoid stretch.

- Hold on for thirty seconds.

- Continue on the opposite side.

Chair Lean

- Take a seat in a chair.

- Hold onto the chair’s side with your right hand.

- Maintain a completely relaxed shoulder.

- Your entire body should be leaned to the left.

- Put your chin down and in.

- Lead your head in a leftward direction.

- Press down with your left hand while placing it on the right side of your head.

- Try to feel the proper Sternocleidomastoid stretch.

- Hold on for thirty seconds.

- Continue on the opposite side.

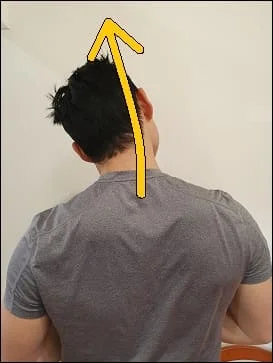

Neck Elongation

- Put your chin down and in.

- Move your head over to the right.

- The right side of your neck should be extended upward.

- Try to feel the right side of the neck being stretched.

- Switch sides.

- Do thirty repetitions.

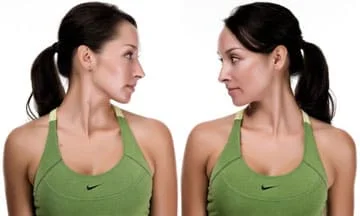

Head tilts

- Pose with your back to the front.

- Breathe out while lowering your right ear gradually to your shoulder.

- To make the stretch deeper, gently squeeze your head with your right hand.

- Feel the stretch from your collarbone to the side of your neck as you hold for a few breaths.

- Inhale and take a step back to where you were before.

- On the other side, repeat.

- Perform ten slants per side.

Neck rotations

- Pose with your back to the front.

- Breathe out, then slowly turn your head to the right while maintaining a downcast, relaxed posture.

- Breathe in, then come back to the center.

- Take a breath out and glance over your left shoulder.

- Make ten turns around each side.

Chin tuck

Assume an axis through your ears, tuck your chin toward your chest, and begin by reclining on your back.

Take care not to use the side of the neck’s sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Hold the tuck for five seconds.

Do ten repetitions of this workout.

You should perform three sets of this workout for optimal results.

Prone Cobra Exercise

In order to complete this workout, lie face down on the ground and use gravity as resistance while reinforcing.

To begin, place your forehead on a rolled-up hand towel for comfort as you lie face down on the ground.

Place your arms at your sides with your palms on the ground.

Raise the hands off the ground and squeeze the shoulder blades together.

Turn your elbows in, your palms out, and your thumbs up.

Raise your forehead gradually so that it is about an inch off the towel, and your eyes should be toward the floor.

For seven to ten seconds, hold the position.

Perform ten iterations.

Isometric Neck Exercise

Keep your body upright and position both hands behind your neck.

Attempt to compress the hands with the neck.

Both hands should hold their aligned position for four to five seconds while resisting the neck muscles.

After that, they should relax.

Do 8 repetitions on the first day and 10 reps on the second.

Work out your forehead and both sides of your neck.

Apply pressure on the side of your head to complete this exercise.

After eight repetitions, switch sides.

Tilted forward flexion exercise

Tilt your head slowly to the left.

Apply pressure with the neck muscle while using the left hand to provide resistance.

After holding for five to ten seconds, return to the starting position.

Additionally, slowly tilt your head to the opposite side.

Hold for 5-10 seconds.

Return to where you were before. Perform ten iterations.

Upward Plank Exercise

By gently hanging your head back and downward in this pose, you can ease tension in your shoulders and neck.

The shoulder, chest, and SCM muscles are stretched and lengthened by this exercise.

To prevent the spine from being compressed, make sure the back of the neck is completely relaxed.

You can stretch the back of the neck and tuck the chin into the chest if you find it difficult to let the head drop back.

Specifically, using the neck muscles without exerting yourself.

You can also allow the head to recline back against a wall, a chair, or a stack of blocks.

Your legs should be straight in front of you as you sit down to complete this exercise.

Alongside the hips, press the palms against the surface.

Raise your hips and place your feet beneath your knees.

Straighten your legs to deepen the position.

Let the head fall back and open the chest.

As long as 30 seconds, hold.

Repeat this stance three times.

Revolved Triangle Exercise

Begin by placing yourself around four feet away.

Place your left toes out at a little angle and your right toes forward.

Face forward and square your hips in the same direction as your right toes.

Raise your arms so that they are parallel to the floor at the sides.

When your torso is parallel to the ground, stop folding forward by gradually hinging at the hips.

Place your left hand anywhere you can reach, such as a block, the ground, or your leg.

Extend your right arm straight up, keeping your palm facing away from your body.

Turn your head to face upward in the direction of your right thumb.

Exhale to turn your neck so that you are staring at the ground.

As you raise your head back up, take a breath.

You can hold this stance for up to a minute, but during that time, keep your upper body steady and keep rotating your neck.

Execute on the other side.

Sternocleidomastoid Muscle Strengthening Exercise

Neck Flexion and Extension

- When sitting or standing, maintain your back straight.

- Feel the soft stretch at the back of your neck as you slowly lower your chin towards your chest.

- Take a few seconds to hold this position, then move back to the starting position.

- Then, carefully turn your head back so that you are facing the ceiling.

- Return to the beginning position after holding this position for a short while.

- Repeat the exercise eight to 10 times.

Resistance Band Neck Exercise

- When sitting maintain your back straight

- Using your right hand, hold one end of a resistance band, and your left hand, the other.

- The resistance band should be sitting on your neck behind your head.

- Using the band as resistance, gently press your head backward to activate the muscles in the front of your neck.

- After a few seconds of holding this position, release it.

Neck Rotation

- Maintain a straight spine whether you sit or stand comfortably.

- As you feel a stretch in the left side of your neck, slowly move your head to the right as far as is comfortable for you.

- Keep your posture for five to ten seconds.

- Return your head to the center slowly.

- Repeat the motion, rotating your head to the left so that you can feel the stretch on the right side of the neck.

- Keep your posture for five to ten seconds.

- Perform 8–10 repetitions of this exercise on each side.

Upward Plank

- In allowing your head to hang passively back and down, you can ease tension in your shoulders and neck by striking this stance. This stretches and lengthens the shoulder, chest, and SCM muscles.

- Avoid compressing your spine so the back of your neck is completely relaxed. You can stretch the back of your neck and tuck your chin into your chest if you find it uncomfortable to let your head drop back. Concentrate on using your neck muscles without exerting too much force.

- Another option is to let your head hang back on a support structure like a chair, the wall, or a stack of blocks.

- Seated, with your legs out in front of you, adopt the position.

- Alongside your hips, press your palms into the earth.

- Raise your hips and tuck your feet beneath your knees.

- Straighten your legs to deepen the position.

- Lean your head back and open your chest.

- As long as 30 seconds, hold.

- Repeat this stance three times.

Head Lifts

Raise your head so that your chin is pointed upwards, using your hands to gently support it.

Hold this posture for five seconds, then gently return your head to the floor.

Your entire neck should feel slightly stretched, particularly at the SCM muscles on either side of your neck.

If necessary, you can alter this workout by supporting your neck during the lift with a rolled towel.

This will ensure that you can retain the correct form throughout the action and aid in giving additional support.

Shoulder Shrugs

The first step in doing this exercise is to stand or sit up straight, with your back straight.

Then, before switching sides, slightly tilt your head to the left until you feel a slight strain along the right side of your neck.

Depending on how comfortable you are, hold each position for ten to fifteen seconds before repeating up to four times on each side.

Seated Neck Stretch

With your back to the chair and your head up, extend your right hand above your head and use your fingertips to touch the left side of your face.

While applying light pressure with your right hand, turn your head gently in the direction of your right shoulder.

The muscles on the left side of the neck should feel nicely stretched.

Hold for fifteen to thirty seconds, then gradually release and return to the center.

Focus on taking slow, deep breaths that help you sink deeper into the stretch with each repetition as you perform the exercise a few times on each side.

This will aid in releasing any stress or tightness from those muscles and help them become more flexible.

Conclusion

The sternocleidomastoid muscle is the only neck muscle that is important for various head and neck movements. It enters the temporal bone’s mastoid process after emerging from the clavicle and sternum. This muscle is in charge of laterally flexing the neck, rotating the head to the other side, and flexing the neck forward.

The sternocleidomastoid muscle is affected in several clinical diseases in addition to its mechanical roles. It may become strained or injured as a result of abuse or trauma, which can cause neck pain and restricted range of motion. In addition, tension headaches and neck pain may be exacerbated by stiffness or spasms in this muscle.

Healthcare workers, particularly those with specializations in physical therapy, sports medicine, and orthopedics, must comprehend the structure and function of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. To improve total neck function and lessen patient suffering, sternocleidomastoid dysfunction symptoms can be effectively assessed, treated, and rehabilitatively achieved.

FAQ

Why is it called sternocleidomastoid?

Its name comes from its two beginnings and the insertion of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. “Cleido” and “stereo” denote the clavicle and sternum, respectively, while “mastoid” denotes the muscle’s insertion, the mastoid process.

What is the function of the sternocleidomastoid muscle?

One of the biggest and most visible cervical muscles is the sternocleidomastoid. Flexion of the neck and head rotation to the other side are the main functions of the muscle. The accessory nerve innervates the sternocleidomastoid.

What nerve supplies the SCM?

The accessory nerve (sometimes called cranial nerve XI) plus the second and third cervical nerves (C2 and C3) make up the sternocleidomastoid muscle’s nerve supply. The sternocleidomastoid receives its proprioceptive information from the second and third cervical nerves.

How do you relieve SCM tension?

To reduce pain and inflammation, use hot or cold therapy.

stretches the muscle fibers to make them stronger and longer.

To relieve tension and relax the muscles, massage.

treatment using osteopathic manipulation.

Physiotherapy.

How do you strengthen the sternocleidomastoid muscle?

Pull your shoulder blades together behind you and gently tilt your chin upward to make your face as parallel to the ceiling as you can. Next, slowly lower it to your chest. Perform these exercises slowly for five to ten seconds, then release the tension and gradually stand back up.

What is another name for SCM muscle?

More than 20 pairs of muscles work on the neck, including the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM). The SCM performs a variety of tasks and has two innervations. It is a muscle that can be felt on the surface that is significant as an anatomical landmark in the neck region and as a component of neuromuscular disorders like torticollis.

How should I sleep with a tight Sternocleidomastoid?

The two sleeping positions that are least stressful on the neck are lying on your side or back. If you sleep on your back, maintain the typical shape of your neck by using a round pillow and placing a broader pillow under your head.

What are the symptoms of sternocleidomastoid?

Having trouble keeping your head up.

confusion.

Unbalance or lightheadedness.

Muscular exhaustion.

Queasy.

Discomfort in the back of your head, neck, or jaw.

Soreness in your cheek, molars, or ears.

Feeling ear ringing.

What are the benefits of sternocleidomastoid massage?

Mitigating headaches and neck pain can be achieved by applying massage treatment to the Sternocleidomastoid muscle. Among the neck’s greatest superficial muscles is this one. When the head and neck are in the forward and backward positions, it aids in maintaining stability.

What are some interesting facts about the sternocleidomastoid muscle?

One of the biggest and most visible cervical muscles is the sternocleidomastoid. Flexion of the neck and head rotation to the other side are the main functions of the muscle. The accessory nerve innervates the sternocleidomastoid.

9 Comments