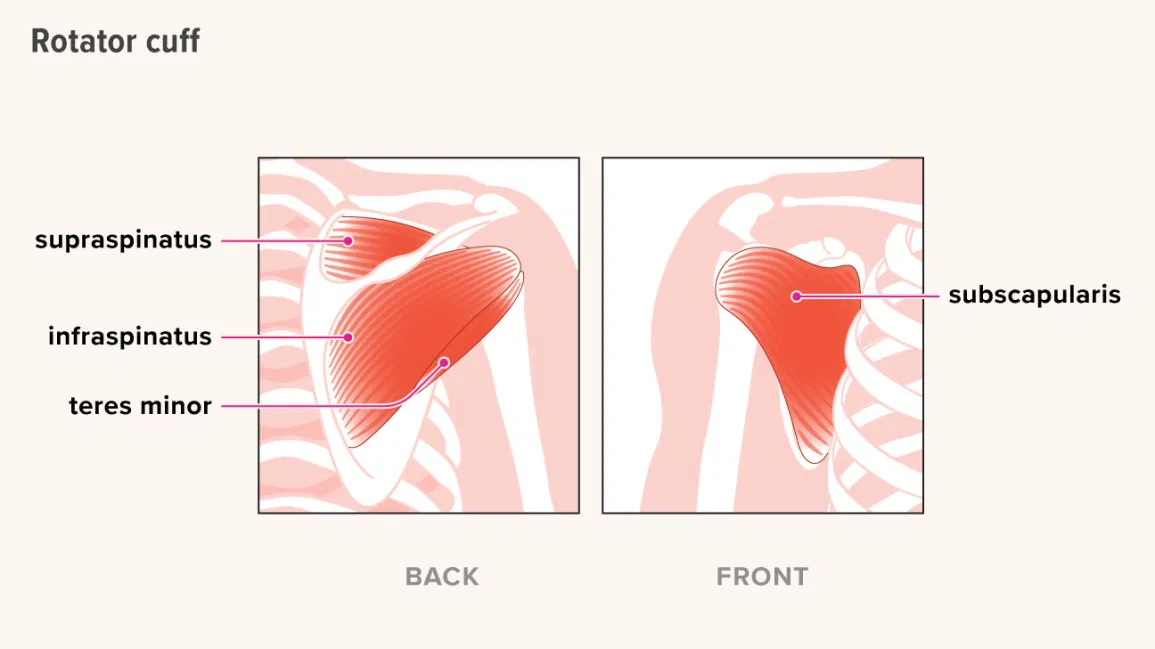

Rotator Cuff Muscle

Introduction:

- A collection of muscles in the shoulder called the rotator cuff maintains the stability of the glenohumeral joint while permitting a great range of motion.

- Subscapularis

- Infraspinatus

- Teres minor

- Supraspinatus

- “SITS” is a useful word to help you recall these muscles.

- The glenohumeral joint, which consists of a tiny glenoid cavity and a huge spherical humeral head, is a ball and socket joint. The joint is extremely movable due to its anatomy but also quite unstable. Together, the glenohumeral ligaments, the capsule, the labrum, the negative intraarticular pressure, and other non-contractile glenohumeral tissues (static stabilizers) and the contractile glenohumeral muscles (dynamic stabilizers), like the rotator cuff muscles and the long head of the biceps brachii, provide stability in the shoulder.

Structure and Function of rotator cuff muscles:

- By applying compression on the humeral head against the glenoid, the rotator cuff’s principal biomechanical function is to support the glenohumeral joint. These four muscles enter into the humerus after emerging from the scapula. The inferior aspect of the joint is left exposed when the rotator cuff muscles’ tendons combine with the joint capsule to form a musculotendinous collar that encircles the anterior, superior, and posterior parts of the joint. This configuration is significant because the humerus typically moves inferiorly through the exposed portion of the joint, resulting in shoulder luxations. The rotator muscles tighten during arm motions, preventing the humeral head from slipping and enabling a full range of motion as well as stability.

- Additionally, through assisting with abduction, medial rotation, and lateral rotation, rotator cuff muscles assist in shoulder joint mobility.

- Subscapularis: Medial (internal) rotation of the shoulder

- Supraspinatus: Abduction of the arm

- required during the first 0–15 degrees of shoulder abduction.

- The arm can be abducted beyond 15 degrees by the deltoid muscle.

- Infraspinatus: Lateral (external) rotation of the shoulder

- Teres Minor: Shoulder lateral (external) rotation

- Every muscle can be assessed separately during a physical examination according to its unique motions.

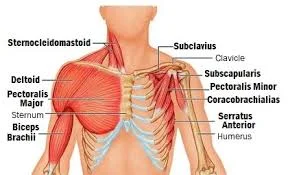

Subscapularis muscle:

Description of subscapularis muscle:

- The large, triangular subscapularis muscle originates from the subscapular fossa. The word “subscapularis” translates to “under (sub) the scapula,” or wing bone.

- Out of the four rotator cuff muscles, the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor are the biggest and strongest. The biggest and strongest rotator cuff muscle is the subscapularis.

Origin:

- the anterior aspect of the scapula, or the medial two-thirds of the subscapular fossa.

Insertion:

- The fibers combine to produce a tendon that enters into the front of the shoulder joint capsule and the lesser tubercle of the humerus.

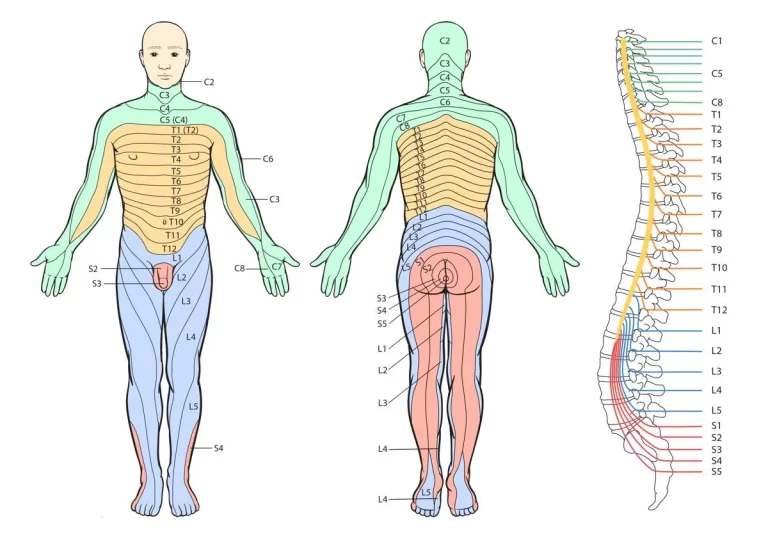

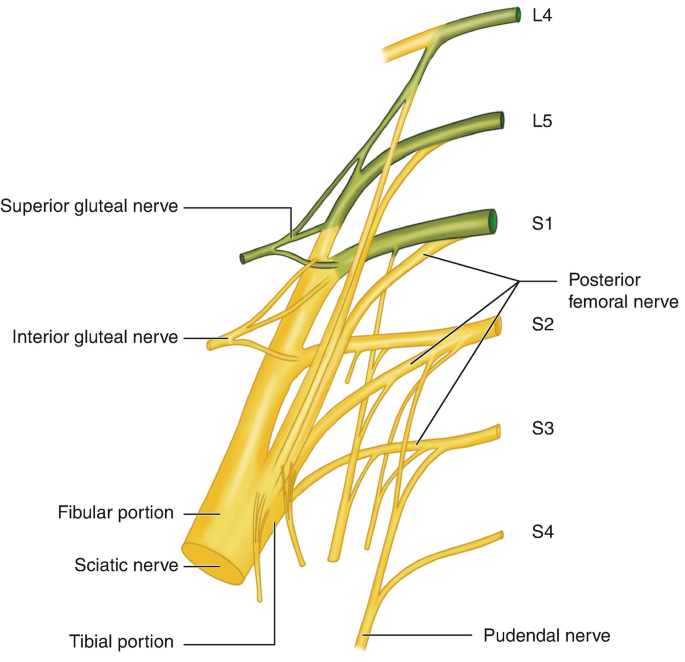

Nerve Supply:

- The posterior nerve of the brachial plexus gives rise to the upper and lower subscapular nerves (C5–C6), which innervate the subscapularis.

- The top portion of the subscapularis is supplied by the upper subscapular nerve.

One of the two branches of the lower subscapular nerve supplies the lower portion of the subscapularis.

Blood Supply:

- The subscapular artery, a branch of the axillary artery, provides the subscapularis muscle with its main blood supply.

Lymphatics:

- The lymph nodes in the axilla receive lymph drainage.

Action:

- The humerus’s internal rotation is its primary function. In specific postures, it aids with shoulder adduction and extension.

- The activities that this muscle produces are significantly influenced by arm position:

- The subscapularis pushes the humerus downward and forward as the arm is elevated.

The insertion of the subscapularis can function as an origin and cause the inferior border of the scapula to abduct when the humerus is fixed.

Function:

- The Subscapularis, a component of the rotator cuff, is crucial for shoulder stability.

Pathologies:

- There are three possible trigger sites in the subscapularis, the two most prevalent of which are close to the muscle’s outer border. Thankfully, the inside border of the muscle trigger point is far less common as it is quite difficult to palpate and release by hand. Most often felt in the posterior shoulder region, pain referred from subscapularis trigger points can also be felt along the back of the upper arm and into the shoulder blade region. There may also be a distinct “band” of transferred pain that surrounds the wrist. The patient usually knows that they have wrist discomfort, but they do not believe that it is connected to their shoulder ache.

- Throwing often causes injuries to it. Applying pressure to the tendon insertion inside the upper arm will cause discomfort and tenderness. Pain when moving the shoulder, particularly with the arm lifted above the shoulders, is one indicator of subscapularis tendinitis.

- An overworked subscapularis muscle may give you the sensation that you are unable to raise your arm. It might perhaps be the cause of your frozen shoulder.

Tests For Subscapularis:

Lift-Off Test:

- The lift-off test, often known as “Gerber’s Test,” was first explained by Gerber and Krushell in 1991.

- When examining a standing patient, the patient is requested to place their hand behind their back such that the dorsum rests on the area of the mid-lumbar spine. Dorsiflexion of the hand raises it off the back by extending at the shoulder and preserving or enhancing internal rotation of the humerus.

- A typical lift-off test consists of the ability to actively raise the hand’s dorsum off the back. When the dorsum cannot be moved off the back, the lift-off test is abnormal and suggests a ruptured or dysfunctional subscapularis.

Bear Hug Test:

- The patient is told to do the Bear Hug Test by positioning their elbow in front of their chest at its maximum anterior translation position and placing the palm of the affected arm on the shoulder of the individual in the opposite posture. The doctor places an external rotational force on the patient’s forearm and instructs the patient to hold that posture.

- If the patient is unable to hold his arm in place or exhibits weakness in internal rotation as compared to the opposite side, the test is positive and suggests a tear or dysfunction in the subscapularis muscle.

Belly Press Test:

- The affected arm is positioned to the side, the shoulder flexed to a 90-degree angle, and the palm rests on the patient’s abdomen to do the Belly Press Test. The patient is directed to do an internal rotation by pressing the palm of his hand against his abdomen. If the patient’s internal rotation was weaker on one side while it was stronger on the other, or if the internal rotation was applied to his belly instead of his shoulder or elbow, the test was considered successful.

Treatment of subscapularis:

- Conservative treatment for subscapularis tendonitis and tendinopathy includes rest, ice, analgesics, activity moderation, and physical therapy. In the beginning, using cold helps lessen discomfort and inflammation.

- Use the thumb method to massage the subscapularis muscle. First, feel the muscle contract; then, release the tension and begin rubbing. Be careful not to massage your nerves along with the muscle. If not, you may have pain for many days due to overstressing the nerves rather than the muscle in your armpit.

Infraspinatus muscle:

Description:

- A thick, triangular muscle is one of the four muscles that comprise the rotator cuff of the shoulder.

Origin:

- The scapula’s infraspinatus fossa, which covers the muscle and divides it from the teres major and minor, is home to some fibers that originate from the infraspinatous fascia.

Insertion:

- The posterior aspect of the humerus’s greater tuberosity and the capsule around the shoulder joint.

Nerve Supply:

- C5 and C6 suprascapular nerves. It begins at the superior trunk of the brachial plexus. It supplies both the supraspinatus and the infraspinatus by extending laterally over the lateral cervical area.

Blood Supply:

- Arteries circumflexing and suprascapular.

Lymphatics:

- The lymphatic drainage system is primarily managed by the rear, or subscapular, nodes. The subscapular nodes are a group of six or seven lymph nodes situated along the posterior axillary fold.

Action:

- Infraspinatus is:

- The primary shoulder joint external rotator.

It facilitates the development of shoulder extension.

It abducts the scapula’s inferior angle while the arm is stationary.

- The primary shoulder joint external rotator.

Function:

- It supplies the main muscular force needed for the shoulder’s external rotation.

- It stabilizes the shoulder complex together with the other rotator cuff muscles.

Clinical Relevance:

- Compression on the suprascapular never around the scapular notch is often indicated by atrophy in the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles. Overhead athletes and SLAP lesions might exhibit this type of compression. Compression of the suprascapular nerve in the spinoglenoid notch can cause isolated weakness or atrophy in the infraspinatus muscle; however, ganglion cysts are often the cause of compression of the nerve in the spinoglenoid notch.

- According to research by Simons et al., pain attributed to the anterior and middle deltoid areas is linked to trigger points in the infraspinatus muscle. Shoulder pain may be alleviated by myofascial release treatments applied to the infraspinatus muscle.

Assessment:

- The arm is positioned in neutral abduction or adduction with the elbow flexed 90 degrees to assess the infraspinatus muscle. Shoulder lateral rotation be performed against resistance; if pain or weakness is felt, the test is considered positive.

Teres minor muscle:

Description:

- The teres minor is a thin muscle that is situated deep to the deltoid, above the teres major and triceps brachii, and below the infraspinatus. It is a member of the Rotator Cuff’s four muscles.

Origin:

- The top two-thirds of the scapula’s posterior surface’s lateral margin.

Insertion:

- The tendon that emerges from the upper fibers attaches to the inferior aspect of the humerus’s greater tubercle. The inferior facet of the larger tubercle of the humerus is exactly where the lower fibers enter into the bone.

Nerve Supply:

- The posterior chord of the brachial plexus gives rise to the axillary nerve, which roots at C5 and C6.

Blood Supply:

- the posterior circumflex humeral artery, the circumflex scapular artery, and the subscapular artery.

- The third and furthest distal segment of the axillary artery gives birth to the subscapular artery and the posterior circumflex humeral artery.

Action:

- External rotation of the shoulder joint is the primary result of Teres Minor and Infraspinatus.

- It supports the shoulder’s adduction and extension.

- Abducts the scapula’s inferior angle after the humerus is stabilized.

Function:

- Teres Minor plays a crucial role in stabilizing the shoulder joint and assisting in keeping the humeral head in the glenoid cavity of the scapula when working in tandem with the other rotator cuff muscles.

Assessment: Hornblower’s sign:

- The teres minor can be examined for injuries, especially rips, using Hornblower’s sign. The patient’s arm should be 90 degrees in the scapular plane with the elbow bent. Next, the patient will externally spin to produce a “field goal” symbol in opposition to resistance. If the patient cannot rotate their shoulder externally, a sign of mild disease, the test is considered positive.

Supraspinatus muscle:

Description:

- The smallest of the four muscles that make up the shoulder joint’s rotator cuff, the supraspinatus is located in the supraspinatus fossa. Of the rotator cuff muscles, it is thought to be the one that is placed most superiorly. It passes through beneath the acromion.

Origin:

- The scapular fossa supraspinatus. a little indentation above the spine in the scapula’s body.

Insertion:

- Greater tuberosity of the humerus, superior facet.

Nerve Supply:

- The superior trunk of the brachial plexus, suprascapular nerves C5 and 6.

Blood Supply:

- Two scapular arteries: the dorsal and suprascapular. Although it can originate directly from the third portion of the subclavian artery, the suprascapular artery usually arises as a branch of the thyrocervical trunk, a branch of the subclavian artery.

Action:

- When it is the primary agonist, it abducts the arm from 0 to 15 degrees.

- Helps the deltoid generate abduction up to 90 degrees beyond this range.

Function:

- Shoulder Stability:

- One part of the Rotator Cuff that helps resist the forces of gravity that pull the weight of the upper limb down at the shoulder joint is the supraspinatus.

- Additionally, it aids in stabilizing the shoulder joint by maintaining the humerus’s head firmly pushed medially on the scapula’s glenoid fossa.

Active Movement:

- It is widely believed that supraspinatus plays a crucial role in initiating shoulder abduction.

- When the shoulder muscles were studied in 2011 using electromyography, the results showed that the supraspinatus was regularly activated before the conclusion that The supraspinatus seemed to be one of the muscles that “initiates” these forces regularly. The anterior translational forces produced during flexion seemed to be counterbalanced by the posterior rotator cuff muscles. The writers define flexion as a limb’s capacity to move in every situation.

Tests for Supraspinatus:

- A popular orthopedic examination test for supraspinatus impingement or integrity of the supraspinatus muscle and tendon is the empty can test, which is also performed in conjunction with the full can test. Taking the test while standing or sitting is typically simpler. One of the examiner’s hands stabilizes the shoulder girdle on the side that will be evaluated. The arm to be examined is brought into complete internal rotation, with the thumb pointing down as though emptying a beverage can, and 90 degrees of abduction in the plane of the scapula (forward flexion of approximately 30 degrees) The patient resists when the examiner’s other hand presses downward on the superior portion of the distal forearm. Indicators of a positive Empty Can Test include considerable weakness and/or discomfort.

Clinical signification of rotator cuff:

- Supraspinatus muscle: This muscle is assessed using Jobe’s test, also referred to as the “empty can” test. Pressing down on the arm, the arm is rotated internally (thumb pointing to the floor) and abducted 90 degrees. If you feel this is weak or unpleasant, the test is affirmative.

- Infraspinatus muscle: This muscle is tested by lateral rotation against resistance while the arm is in a neutral abduction/adduction posture and the elbow is flexed.

- Teres minor muscle: The hornblower’s test is used to assess this muscle. It involves extending the elbow to a 90-degree angle, rotating the arm laterally against resistance, and maintaining an abduction posture of 90 degrees. If you feel this is weak or unpleasant, the test is affirmative.

- Subscapularis muscle: Utilizing the “lift-off” and “bear hug” tests, this muscle is assessed. The patient performs the lift-off test by bringing their hands around their back to their lumbar region, palms out. If the patient is unable to raise their hands off their back, the test is considered successful. In the bear hug test, the patient tries to resist the examiner’s pulling of their ipsilateral palm away from their deltoid.

Exercise of Rotator cuff tear:

Exercise of open chain method:

Side-lying external rotation:

- Lying on your unaffected side, insert a small cushion between your affected arm and body. With the elbow bent and fixed to the side, raise the affected arm into the external rotation. Gradually return to the beginning position, then do it again.

Shoulder extension:

- On a table, assume the prone position. The concerned arm is hanging vertically to the floor. Point the thumb outward and raise the arm straight back towards your hip. Lower the arm gradually and repeat.

Prone horizontal abduction:

- With the injured arm dangling straight to the floor, lie prone over a table. With the thumb pointed outward, extend the arm out to the side, parallel to the ground. Slowly lower the arm, then do it again.

90/90 external rotation:

- Lay down on a table with your face down. The shoulder is abducted to a 90° angle and the arm is supported by the table. The elbow bent to ninety degrees. Keep the elbow and shoulder stationary as you rotate the arm externally. Gradually return to the beginning position, then do it again.

Exercise of close chain method:

- The therapist applies rhythmic stabilizing or perturbation stresses to the patient when their shoulder is in the scapular plane and 90 degrees elevated.

- The last stages of rotator cuff injury treatment include proprioception training, progressive resistive strengthening, and activities tailored to the patient’s particular sport. Thrust and non-thrust manipulation (TSTM) of the cervicothoracic spine and/or ribs may result in a significant reduction in pain and disability for patients whose primary complaint is shoulder discomfort. The restoration of motion between adjacent vertebrae can be used to describe the application of TSTM in shoulder patients. This is what is known as a reflexogenic system.TSTM can enhance general functional performance and shoulder mobility.

Summary:

Adults with disability and discomfort in their shoulders often have tears in their rotator cuffs. Every year, more than two million Americans visit their physicians because of rotator cuff injuries.

Your shoulder may become weaker if you have a rotator cuff tear. This implies that performing certain everyday tasks, like combing your hair or putting on clothes, may become uncomfortable and challenging.

FAQ:

What anatomy is the rotator muscles?

The shortest bundles, ranging from one (short rotatores) to two segments (long rotatores), are found in the deepest muscles of the transversospinalis group. a component of the body’s deep, core muscle groups that serve as dynamic stabilizers and assist with all limb movement.

Which four components make up the rotator cuff?

In accordance with the initial letter of each of their names—Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus, Teres minor, and Subscapularis, respectively—they are also referred to as the SITS muscle. The muscles that create a cuff around the glenohumeral (GH) joint originate from the scapula and attach to the head of the humerus.

Which rotator cuff muscle sustains injuries most frequently?

The tendon on top of the shoulder, known as the supraspinatus tendon, is the most often damaged tendon in the rotator cuff.

The rotator cuff muscles are located where?

The head of the upper arm bone is securely held within the shallow socket of the shoulder by a network of muscles and tendons called the rotator cuff.

What is the shoulder muscles’ anatomical makeup?

The rotator cuff is the main muscle group that supports the shoulder joint. The four muscles that comprise the rotator cuff are the subscapularis, teres minor, infraspinatus, and supraspinatus. When the rotator cuff muscles are inserted into the proximal humerus, they combine to create a musculotendinous cuff.

What makes up the rotator cuff ligaments’ anatomy?

There are four muscles in the rotator cuff. These muscles include the teres minor, infraspinatus, supraspinatus, and subscapularis. The musculotendinous cuff is formed by the close fusion of the short, flat, wide tendons that terminate these muscles with the fibrous capsule.

References:

- Rotator Cuff. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Rotator_Cuff

- Hecht, M. (2019, November 26). Rotator Cuff Anatomy Explained. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/bone-health/rotator-cuff-anatomy

3 Comments