Lumbar Spondylosis

What is Lumbar Spondylosis?

Lumbar spondylosis is a degenerative condition affecting the discs, vertebrae, and associated facet joints in the lower portion of the spine called the lumbar region. Specifically, it involves wear and tear damage and abnormalities related to the lumbar spinal discs. The intervertebral discs act as shock absorbers between the vertebrae and allow flexibility and movement of the spine.

In lumbar spondylosis, these discs progressively lose integrity, hydration, and the ability to effectively absorb mechanical stresses and loads applied to the spine. This leads to additional stress being transferred to other structures of the lumbar spine including the vertebral bodies, neural structures, muscles, and ligaments.

There are a few key features defining lumbar spondylosis:

- Chronic degradation of the lumbar intervertebral discs refers to the fibrocartilaginous structure between adjacent vertebrae in each spinal segment. This causes the discs to shrink in height and lose elasticity.

- Development of bony projections called osteophytes along the edges of the vertebral bodies adjacent to the damaged discs. These bone spurs may grow to encroach on the space available for the spinal cord and nerve roots.

- Degeneration of the facet joints between vertebrae, which help provide stability and guide motion in the spine. Arthritic changes cause these small joints to become enlarged, develop cysts, and lose their mobility.

- Chronic inflammation induced by structural abnormalities puts pressure on nerve roots exiting the spinal cord, resulting in neurological symptoms like pain, numbness, and weakness.

In summary, lumbar spondylosis refers to the progressive multifactorial spinal column degeneration concentrated in the lumbar or lower back region which involves the discs, vertebrae, surrounding joints, ligaments, and connective tissue.

Anatomy

The specific anatomy involved in lumbar spondylosis includes:

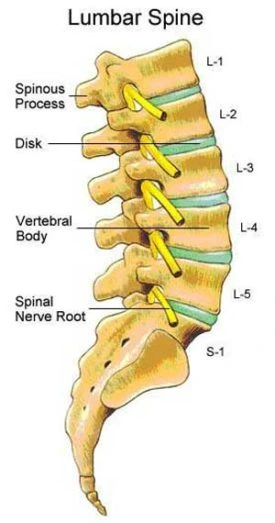

- Lumbar Spine: The lumbar spine refers to the second to lowest portion of the vertebral column located below the thoracic spine and above the sacrum. There are typically 5 lumbar vertebrae labeled L1 to L5. This is the main area of the lower back.

- Intervertebral Discs: The discs provide cushioning between adjacent lumbar vertebrae to transmit loads and allow flexibility including bending and twisting motions. Each disc has a tough fibrous outer layer called the annulus fibrosus surrounding an inner gel-like nucleus pulposus.

- Vertebrae and Facet Joints: The functional unit of the lumbar spine encompasses a vertebra, intervertebral discs above and below, plus a paired set of facet joints at the posterior. These joints provide stability and guide motion. Osteophyte formation and arthropathy affect their form and function.

- Spinal Canal and Nerve Roots: At the center of the column is the spinal canal carrying the cauda equina nerve roots that exit out through the neural foramen. Compression and inflammation of these structures give rise to neurological symptoms. Anatomical narrowing of the central or lateral space may occur.

Epidemiology and Causes

Epidemiology refers to the data and statistics on how common the condition is, while etiology refers to the specific risk factors and causes behind the disease.

Prevalence

Lumbar spondylosis has an extremely high prevalence rate, with over 85% of individuals over the age of 60 demonstrating radiographic evidence of degenerative changes like disc space narrowing and osteophytes. It is considered part of generalized “spine aging” as time takes its toll on the structural components. The degree of symptoms however can vary substantially from mild to severely disabling pain. Prevalence increases with each decade of life. There is equal male-to-female representation.

Risk Factors

Several contributing factors increase the risk of developing symptomatic lumbar spondylosis. The main predictors include:

- Age: Advanced age is the strongest predisposing variable, as the cumulative effects of mechanical stress and cellular changes degrade the structural integrity of the lumbar spine. The discs and joints become less resilient.

- Genetics: Research shows that generalized spinal osteoarthritis and disc degeneration have a heritable component passed down genetically. Certain varieties of collagen or phenotypes lead to increased vulnerability.

- Overuse and Injuries: Repeated occupational or sports injuries from excessive loading or torsional movements take their toll over time. Episodes of acute back strain or sprain create a cascade of inflammation.

- Poor Biomechanics and Posture: Sustained faulty posture like slouching adds asymmetric forces and compression contributing to wear and tear. Lifting heavy objects with a bent spine multiplies pressure.

- Obesity: Excess body weight transmits higher loads per unit area on the lumbar discs and facet joints, causing structural breakdown. The rate of spondylosis worsens with obesity.

- Smoking: Studies reveal worse disc degeneration among smokers, linked to coughing pressures, reduced blood flow, and abnormal matrix turnover. Nicotine may have direct toxic effects on discs.

In summary, age-related disc and spinal joint degeneration is universal but certain genetic and lifestyle factors make patients more prone to earlier onset or more rapid progression of lumbar spondylosis. The higher symptom burden warrants prevention education.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis refers to the biological mechanisms by which the structural damage and symptom manifestations of lumbar spondylosis occur over time. It is a progressive cycle of joint degeneration, inflammation, and neuropathic compression.

Degenerative Cascade

The intervertebral discs and facet joints of the lumbar spine undergo age-related physiological changes that diminish shock absorption and height, initiated by reduced hydration and altered biomechanical forces. This triggers compensatory growths like osteophytes subjecting the area to further abnormal stresses, perpetuating additional arthritic remodeling.

Chronic Inflammation

The pathological changes provoke the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines from the matrix breakdown products. Mediators like IL-1, IL-6, TNF-alpha, prostaglandins, and substance P act locally on nerve fibers eliciting pain sensation and vasodilation while recruiting more inflammatory cells.

Neural Compression

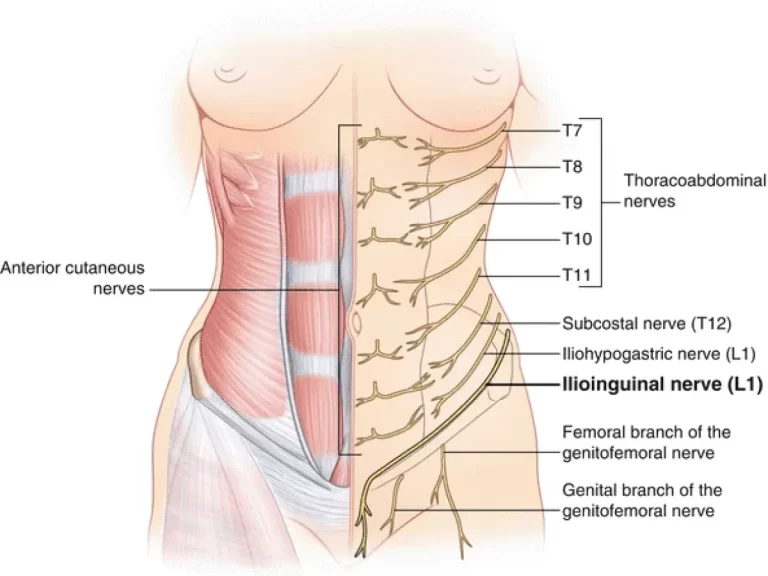

Chronic inflammation and structural changes lead to gradual encroachment on the lateral recess and narrowing of the spinal canal diameter. This compresses the traversing nerve roots of the cauda equina and exiting foramina causing radicular pain, paraesthesia, and weakness along specific dermatomes.

Segmental Instability

As disc height loss, ligamentous laxity, and facet arthropathy progress, abnormal patterns of vertebral slipping and translation emerge. This indicates impaired dynamic spine stability and alignment control further accentuating nociceptive and neurological symptoms.

Overall the interplay between structural failure, inflammation, neural irritation, and postural control deficits drive the clinical picture of pain and loss of function in lumbar spondylosis.

Causes of Lumbar Spondylosis

Aging and Degeneration

- The intervertebral discs lose hydration and proteoglycan content over time leading to a loss of flexibility and elasticity.

- Facet joint cartilage wears down and bony overgrowths with osteophytes form. Joint mobility declines.

- Cellular senescence reduces the ability to maintain and repair the structural integrity of the spinal tissues.

- Age-related conditions like diabetes and atherosclerosis contribute by impairing blood flow to discs and cells.

Accumulated Minor Injuries

- Repeated microtraumas like lumbar muscle strains build up leading to microfractures, inflammation, and gradual tissue deterioration.

- For example, poor lifting habits like hunching forward lead to asymmetric compressive loading and annulus disc tears.

- Whiplash from car accidents and penetrating sports injuries progressively harm spine stability through lingering effects.

Poor Posture Over Time

- Sustained postural faults like forward head carriage, sway back, and flattened lumbar curve disrupt the balance of forces exacerbating joint surface friction and muscle strain.

- This heightens susceptibility to acute disc herniations especially when coupled with asymmetric rotation.

- Over many years poor postural can accelerate degenerative processes.

Obesity/Overweight

- Excess body weight transmits higher loads per unit area on the lumbar discs and facet joints, eventually causing breakdown.

- Abdominal obesity limits the ability to stabilize the spine properly leading to accelerated wear and tear of the supporting structures.

Physical Labor and Overuse

- Repetitive heavy lifting, bending, and twisting required in certain occupations leads to microtrauma and structural fatigue.

- Examples include nurses manually moving patients, construction workers, and athletes like weightlifters who overexert their lower back continually.

- The cumulative toll on spine joint surfaces and ligaments outstrips reparative capacity.

Congenital Abnormalities

- Anatomical anomalies in the vertebrae, facet configuration, or intervertebral disc at birth make the spine more intrinsically vulnerable to developing early spondylosis.

- Certain inherited connective tissue disorders likewise predispose individuals to heightened disc degeneration.

The above factors interact causing a mechanical overloading cascade plus chronic inflammation culminating in accelerated onset of spondylosis. Lifestyle changes and activity modifications can help mitigate risk from some of these triggers.

Symptoms of Lumbar Spondylosis

Patients with lumbar spondylosis typically present with chronic, progressive lower back pain that may refer or radiate to other areas. The precise symptoms depend on which nerve roots and axial structures are being compressed or irritated.

- Dull, aching lower back pain on one side or both sides is common, centered over the lumbosacral junction typically.

- Pain usually worsens with activity especially prolonged standing, walking, bending forward, or arching back.

- Rest, heat, and lying down improve the discomfort. Night pain may disturb sleep.

Referred or Radiating Pain

- Sciatic nerve pain may shoot down the backs of the legs along typical dermatome patterns inducing sensations described as sharp, tingling, burning, stabbing, or electrical.

- Buttock and upper thigh pain are also common referral zones.

- Coughing or sneezing can elicit or exacerbate the radiating quality.

Muscle Spasms and Stiffness

- Paravertebral muscle tightness and spasms develop as the body attempts to splint and protect the inflamed area. Muscular back tension and stiffness accompany the limited mobility.

Neurological Symptoms

- Numbness, tingling, or pins-and-needles sensations may manifest in the saddle region or extending down the legs. This results from inflammatory neuropathy.

- In late cases, significant neural encroachment exists, and patients may develop motor weakness affecting their gait.

Reduced Spine Mobility

- Decreased range of motion manifests during attempted trunk flexion, lateral bending, and rotation movements. This corresponds to the morphological joint surface and disc space narrowing changes.

- As inflammation progresses, rigidity and postural deviations emerge making it painful to adopt normal functional postures.

Symptom onset is generally gradual correlating with progressive degenerative changes, but acute disc herniation or reinjury can rapidly exacerbate intensity. Early recognition facilitates conservative treatment to relieve pain and maintain mobility.

Examination

The clinical examination of a patient with suspected lumbar spondylosis involves a structured multi-part assessment including:

Medical History

- Thorough review of symptoms onset, description of back pain and radiating symptoms, aggravating/relieving factors

- Screening for red flags e.g. trauma, constitutional symptoms needing urgent diagnosis

- Past medical issues, medications, lifestyle, and ADL limitations

- Family history of arthritis/back conditions

Posture Assessment

- Observation of standing and sitting posture from all angles to identify postural abnormalities or antalgic shifts indicative of muscle spasm and inflammation

- Common findings: loss of lumbar lordosis, lateral tilt of pelvis, scoliosis

Physical Exam Maneuvers

- Palpation for tenderness and muscle tension particularly in the lower lumbar region and sciatic nerve routes

- Active and passive range of motion testing showing reduced spinal flexion, extension, side bending, and rotation

- Special tests like straight leg raise reproducing back or leg symptoms

Neurological Exam

- Motor strength testing of major muscle groups of the lower limbs

- Reflex testing at the knees and ankles

- Detailed dermatomal sensory mapping using light touch, pinprick, and vibration stimuli

Functional Capacity Evaluation

- Assessing tolerance for standing, walking, and simulated occupational tasks

- Quantify movement patterns during transitions: sit to stand, climbing stairs

- Identify loading thresholds that aggravate pain

Data gathered from clinical examination combined with imaging helps determine structural damage localize the source of inflammation and formulate appropriate management.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing lumbar spondylosis involves:

Medical History and Physical Exam

- A thorough medical history and neurological physical exam are performed first to characterize the symptoms and deficits.

- This establishes a clinical pattern consistent with an L4/L5 or L5/S1 nerve root compression.

Imaging Studies

X-rays

- Provide visual confirmation of disc space narrowing, vertebral endplate sclerosis, and osteophyte formation.

- Useful for initially evaluating bony anatomy but poor soft tissue differentiation.

MRI

- Gold standard imaging technique due to superior visualization of intervertebral discs, spinal ligaments, and neural structures.

- Can accurately detect disc bulging/herniation, central stenosis, or neuroforaminal narrowing.

- Visualizes modalities of morphological changes in spondylosis.

CT Scan

- Better bony detail than MRI for assessing fine bone anatomy and small fractures.

- Use when MRI is contraindicated or surgery is being planned.

- Radiation exposure risk so not used routinely.

Diagnostic injections

- Facet joint blocks and epidural steroid injections can help pinpoint the spinal level responsible for symptoms when multiple levels are affected.

Laboratory Tests

- Include complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein to exclude infection or inflammatory spondyloarthropathy, which can overlap in presentation.

The combination of results from precise history, radiological studies, and selective injections guides proper diagnosis of primary lumbar spondylosis pathology versus mimics.

Differential Diagnosis

Several conditions can mimic or overlap with the clinical presentation of lumbar spondylosis that should be excluded:

Spinal Stenosis

- Lumbar canal narrowing causes bilateral lower extremity pain, numbness, and neurogenic claudication. Most common mimic.

- Distinguished from spondylosis by the site of compression (central canal vs. lateral/foraminal) and MRI findings.

Herniated Disc

- Acute disc rupture with unilateral leg predominant pain due to nerve root tension.

- Differentiated by acute severity, often pain while supine/at rest, unlike spondylosis. Diagnosis confirmed on MRI.

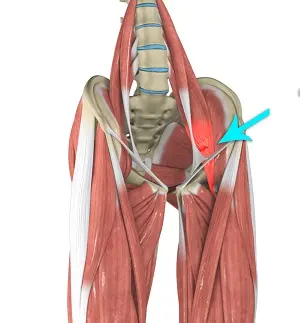

Sciatica/Piriformis Syndrome

- Resembles radicular pain but primary pathology involves pyriformis muscle irritating sciatic nerve.

- Tend to be unilateral symptoms, nocturnal pain, relieved by stretching. No spondylosis changes on imaging.

Spine Infection

- Vertebral osteomyelitis/discospondylitis presents with constitutional sepsis, elevated inflammatory markers, and characteristic MRI signal changes.

Metastatic Spinal Tumors

- Suspect with a history of cancer. Unilateral radiculopathy. Other red flags mandating prompt workup for spinal metastasis.

Vertebral Compression Fractures

- Acute traumatic or pathological fractures must be excluded which can impinge neural structures. Establish a history of trauma and risk factors.

The clinical presentation of progressive bilateral lower back pain and stiffness with advancing age and insidious onset is classic for lumbar spondylosis once dangerous mimics requiring emergency care have been excluded.

Treatment of Lumbar Spondylosis

Non-surgical Treatment

The mainstay of initial management for lumbar spondylosis is non-surgical conservative treatment focused on alleviating inflammation, reducing pain, improving function, and slowing disease progression through a combination of methods:

Lifestyle Changes

- Weight loss if overweight to minimize mechanical loading on the spine

- Regular low-impact aerobic exercise to improve supporting muscle strength

- Employing correct posture and body mechanics during activities

- Firm mattress allowing neutral spine positioning overnight

- Smoking cessation to promote healthy disc matrix turnover

Medications

- Over-the-counter analgesics like NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen) to relieve inflammatory pain

- Muscle relaxants like cyclobenzaprine for acute flare-ups

- Judicious short-term use of oral corticosteroids to rapidly dampen inflammation

- Epidural steroid injections directly at the site-affected roots

Physical Therapy

Best Exercises for Lumbar Spondylosis Video

- Stretching and core muscle strengthening exercise prescription

- Modalities like heat/ice and TENS for symptomatic relief

- Gentle spinal traction and manual therapy for stiffness

- Bracing for extra lumbar support to limit strain

The majority of patients with lumbar spondylosis improve significantly through conservative treatment without needing surgery. Therapies aim to maximize functionality and quality of life through this progressive condition.

Surgical Treatment

For patients with persistent and severe neurological symptoms or functional impairment unresponsive to exhaustive conservative measures, surgical intervention may be warranted. The goals are decompressing irritated nerve roots and stabilizing the spine.

Laminectomy

- Removal of posterior lamina bone and ligaments to relieve pressure on spinal nerves and increase space. Most common surgery performed.

Spinal Fusion

- Joining several vertebrae together with bone grafts and implants to eliminate motion at that segment. Provides stability and prevents irritation.

Disc Replacement

- Involves removing the diseased lumbar disc and inserting a prosthesis to preserve motion and reduce strain on adjacent levels.

Foraminotomy

- Widening of the neural exit foramen canals through bone removal relieving pinched nerve impingement. Often paired with laminectomy.

There are several advantages and disadvantages for each procedure related to long-term effects on mobility, adjacent segment disease, and complication risks. Outcomes are optimized with thorough pre-surgical evaluation and picking the lowest invasive option to match pathology. Many patients still elect to avoid or delay surgery given the risks involved.

Physical Therapy Management

Physical therapists play a critical role in the conservative treatment of lumbar spondylosis through an individually tailored program addressing musculoskeletal dysfunction and teaching self-management strategies:

Therapeutic Exercises

- Prescribing specific strengthening and flexibility exercises for the lumbar and core musculature to provide dynamic spine stability and mitigate structural stresses.

- Aerobic conditioning to improve circulation and endurance of back muscles enabling patients to return to normal functional activity levels.

- Stretching tight posterior chain muscle groups like the hamstrings contribute to lumbar lordosis being lost.

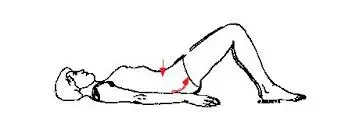

Pelvic Tilt

- Lay flat on your back with your feet flat on the ground and your knees bent at a 90-degree angle.

- Tighten your abdominal muscles, drawing your belly button in towards your spine

- Maintain this contraction while pressing your lower back down into the floor to flatten your spine against the ground

- Hold for 10-15 seconds then relax your stomach and low back muscles

- Repeat for 10 repetitions, taking breaks as needed between sets

- Can do sets of 3 reps, holding the tilt for longer durations each time

- Helps stabilize the spine in neutral alignment reducing painful nerve compression

Dead Bug

- Begin lying on your back with both knees bent at 90-degree angles, feet flat on the floor

- Place your arms out straight at your sides to begin

- Draw in your navel towards your spine, activating your deep core abdominals

- Keeping one knee bent, straighten out the opposite leg, hovering a foot above the floor

- Raise the arm opposite your extended leg up towards the ceiling at the same time

- Avoid letting your arch your back as you lift your arm and leg

- Hold for 5 seconds before lowering arm and leg back down

- Repeat the sequence on the opposite side, completing 10 controlled reps on each side

- Protects spine by training core coordination

Partial Sit Up Curl

- Lie on your back with knees bent and feet flat, arms extended towards your knees

- Draw the belly button in towards the spine to tighten abdominal muscles

- Keep your chin tucked as you exhale and slowly curl your upper body forward off the floor

- Raise shoulders only partially without fully sitting up

- Hold for 3 seconds before lowering back down carefully

- Repeat for 10 repetitions

- Can intensify by holding hands clasped behind the head

- Builds anterior core strength

Gluteal Stretch

- Lie on your back with knees bent at 90-degree angles

- Cross one ankle over to rest on top of the opposite knee

- Grab underneath the thigh of the bottom leg and gently pull towards the chest until a stretch is felt in the buttocks

- If flexible enough can use your hands to draw both legs in to feel a deeper glute stretch

- Hold for 15-30 seconds before releasing the leg and switching sides

- Repeat 2-3 times on each side

- Stretches tight piriformis and hip external rotators alleviating sciatic symptoms

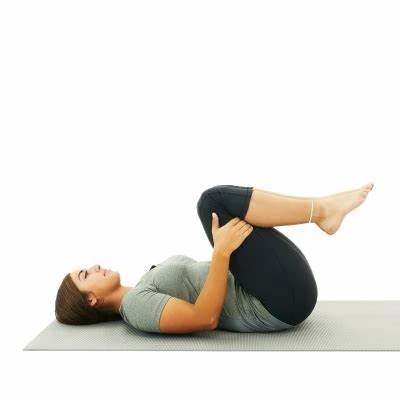

Double Knee to Chest

- Begin lying on your back with both knees bent, feet on the floor

- Engage your core by drawing naval in towards the spine to stabilize the lower back

- Keeping knees together, lift both feet off the floor

- Bring both thighs towards your chest, grasping below knees with hands if able

- Bring knees as close to the chest as possible feeling stretch in the lower back

- Hold for 5 seconds

- Lower legs back to starting position

- Repeat for 10-20 reps

- Stretches lumbar vertebrae and discs

Quadruped Arm and Leg Lift (Bird Dog)

- Wrists beneath shoulders, knees under hips, begin on your hands and knees.

- Tighten abdomen muscles to stabilize your spine in neutral posture

- While maintaining abdominal contraction, raise one arm forwards

- At the same time, slowly lift the opposite leg behind you

- Avoid arching your lower back as you lift your arm and leg

- Hold for 5 seconds before lowering the limb back to start

- Repeat the sequence with the opposite arm and leg

- Complete 10 controlled reps on each side

- Improves core control, back extension strength

Exercises to Avoid

Heavy Weightlifting

- Activities like heavy squats, deadlifts, overhead pressing, and loaded spinal flexion place high amounts of compressive and shear forces on the vertebrae

- This can overstress damaged pars interarticularis or nerves already compressed due to slippage

- Always maintain proper form – avoid rounding lower back during lifts

- Reduce weight used and focus on higher rep sets with lighter loads

- Consider alternatives like machine-based strength training initially

Twisting Motions

- Rotational exercises that incorporate excessive torso twisting should be avoided

- This includes movements like full sit-ups with oblique crunches, Russian twists

- Golf swings, batting strokes, and serves can also over-rotate the spine aggravating nerves

- Modify motions to be more frontal without reaching end ranges of rotation

High Impact Activities

- Running, basketball, tennis, football, and similar sports jar the spine significantly

- Transition to low-impact cardio like swimming, cycling, and elliptical once cleared by PT

- Avoid activities with abrupt stop/start/change-of-directions until repaired

- Modify intensity and include thorough warm-up/cool-downs to minimize injury risk

Consult your physiotherapist to design a personalized exercise program that strengthens your core without putting added strain on the vulnerable spine.

Manual Spinal Mobilization

- A distractive force is applied along the vertical axis of the spine using equipment, allowing herniated discs to be repositioned back inward away from irritated nerve roots. Creates space.

Lumbar Roll Mobilizations

- The patient lies prone while the therapist applies pressure repeatedly with a cylindrical tool perpendicular to stiff facet joints encouraging joint mobility.

Soft Tissue Massage

- Direct muscle stripping, trigger point release, and cross-fiber friction massage techniques applied to tight musculature like lumbar paraspinal relieve spasms.

Postural Retraining

Mirror Visual Feedback

- Patients are taught to stand tall monitoring posture in a mirror while receiving verbal coaching on repositioning pelvis/ribs alignment and correcting imbalances.

Flexion Postures

- Learning proper hip hinge patterns and training core control when bending down to pick objects protecting the spine versus rounding the back.

Modalities for Symptomatic Relief

- Heat, ice, TENS, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation temporarily help relieve muscular back pain and inflammation through various mechanisms like gate control theory and increased blood flow.

Heat Therapy

- Heat packs, warm compresses, ultrasound, and shortwave diathermy are applied to relax muscles, boost blood flow, and relieve spasms before activity.

Cold Therapy

- Ice massages and cryotherapy decrease inflammation, edema, and acute flare pain from lumbar spondylosis.

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)

- Surface electrodes deliver small electrical impulses that modify pain signal transmission based on gate control theory providing temporary symptomatic relief.

Spinal Traction/Decompression

Spinal decompression traction techniques apply gentle stretching forces to the lumbar vertebrae and intervertebral discs, creating negative intradiscal pressure to suction herniated disc material back into place. This also widens the diameter of the spinal canal and neural foramen openings, decreasing inflammation and relieving pressure on nerve roots. Common methods include:

Intermittent Motorized Traction Tables

- Programmable computerized tables allow patients to lie down comfortably while the equipment provides quantifiable distractive forces to the lumbar region in graded time intervals with relaxation phases in between. Force, duration, and number of cycles can be adjusted. This technique has the most clinical research support.

Manual Traction

- The provider uses their bodyweight and handles to apply manual stretch to the lumbar spine for symptom relief, however dosing standardization is more variable. Often used as an adjunct treatment.

Inversion Therapy

- The patient’s body is gently inverted upside down using specialty gravity boots or tilt tables allowing spinal decompression via gravitational pull. Degree and duration are easily titrated.

Braces and Adaptive Equipment

Various types of lumbar braces, mobility aids, adaptive equipment, and ergonomic products can help patients continue important daily activities and reduce strain on the spine:

Lumbar Support Belts and Corsets

- Fitted elastic wraps or semirigid molded plastic braces offer compression and improve proprioceptive awareness helping limit painful spinal motions. Some feature additional stays or panels preventing flexion or rotation beyond a certain range.

Raised Toilet Seats

- Elevating toilet seat height reduces the degree of hip flexion required to sit down or stand up, minimizing low back strain.

Reachers and Grabbers

- Extended gripping tools allow objects to be grasped from the floor or high shelves without having to bend or reach overhead, reducing spinal loading.

Back Braces for Chairs

- An attachable rigid frame with supporters reminds the individual to avoid prolonged slouching during sitting, preventing poor posture and aggravating lumbar spondylosis.

Patient Education

Patients benefit greatly from education on lifestyle modifications and gain a sense of control over managing their spondylosis symptoms through techniques like:

Body Mechanics Training

- Learning optimal biomechanics for common actions like lifting, pushing, pulling, and carrying heavy objects using the legs more than the back. Pelvis and core activation are emphasized.

Posture Training

- Regular practice maintaining proper upright neutral alignment while standing and sitting avoiding slouched positions that cause creep and worsening inflammation. Can use mirrors, tactile cues, and postural braces as reminders.

Home Exercise Programs

- Continued practice of specific stretches, strengthening, and stabilization exercises tailored to their needs promotes circulation, flexibility, and core control between therapy visits. Improves function.

Conservative physical therapy combining manual, exercise-based, and modality treatments allows most spondylosis patients to improve their pain, strength, and endurance and achieve an optimal restored functional status without surgery.

Complications

If not managed properly, lumbar spondylosis can lead to:

Worsening Pain and Loss of Mobility

- Uncontrolled inflammation and structural deterioration result in worsened back and leg pain making routine mobility difficult.

Spinal Stenosis

- Progressive narrowing of central spinal canal diameter from enlarged facet joints and ligamentum flavum can compress cauda equina nerves.

Permanent Neurological Damage

- Severe untreated compression of nerve roots leads to sensory loss, muscle weakness, and impaired bowel/bladder/sexual function.

Disability

- Chronic severe pain, stiffness, and loss of lumbar strength cause major limitations in performing occupational duties and activities of daily living. Can render patients wheelchair-bound.

All the above complications significantly reduce quality of life. That’s why appropriate conservative therapy and lifestyle changes should start early to halt spondylosis progression. Surgery like laminectomy or fusion may still be required in advanced disease.

Summary

Lumbar Spondylosis refers to a degenerative condition affecting the lumbar spine resulting in chronic back pain and stiffness. Specifically, it involves age and injury-related wear and tear damage to the intervertebral discs between spinal vertebrae and the associated facet joints. This leads to a narrowing of disc space height and spinal canal diameter compressing nerve roots.

Symptoms are generally gradual onset of aching lower back pain, loss of mobility, and referred pain in the buttocks or legs. Neurological symptoms like numbness, tingling, or weakness in lower limbs may appear later from nerve compression. Chronic inflammation around the damaged structures is a main disease driver.

Risk factors include older age, trauma history, obesity, poor posture, genetics, smoking, and occupations requiring heavy lifting or repetitive bending. Diagnosis is made by clinical exam and imaging studies such as CT, MRI, or X-ray showing the disc space narrowing, bone spur formation, and degenerative changes characteristic of spondylosis.

Initial management is conservative focusing on pain relief, anti-inflammatory medications, activity modification, physiotherapy, and strengthening exercises for lumbar/core muscles to improve stability and spine extension mobility. If non-surgical treatments are ineffective, procedures to decompress irritated nerves or stabilize symptomatic segments may be warranted.

While spondylosis is to some extent an unavoidable part of aging, increased awareness on avoiding high mechanical spinal stresses throughout life and addressing back pain promptly can help reduce severity and maintain quality of life. Close management by a healthcare team is key to preventing disease progression and disability from complications like spinal stenosis, postural deformity, severe mobility impairment, or chronic neuropathy.

FAQs

What causes lumbar spondylosis?

Lumbar spondylosis is primarily caused by age-related wear and tear as well as cumulative minor injuries to the discs and facet joints in the lower back. Genetics, poor posture, obesity, smoking, and high-impact jobs can accelerate its progression.

What are the most common symptoms?

The most common symptoms are lower back pain that worsens with activity, stiffness that improves with rest, and loss of flexibility or range of motion in the lumbar spine. Neuropathic leg pain, numbness, or weakness can also occur.

How is lumbar spondylosis diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves a physician reviewing medical history and performing a focused neurological exam. Imaging studies like X-rays, CT, or MRI scans help confirm disc space narrowing, bone spurs, inflammation, and nerve compression consistent with spondylosis.

How can I manage my lumbar spondylosis effectively at home?

Home management involves over-the-counter anti-inflammatories, applying heat/ice, exercises to improve core strength and back extension flexibility, maintaining proper posture and body mechanics during daily activities, weight loss if overweight, and lifestyle modifications like smoking cessation.

When should I consider surgery for lumbar spondylosis?

If chronic low back pain and neurological symptoms like leg weakness or foot drop become disabling despite completing at least 6 months of thorough conservative treatment, your physician may discuss surgical options like spinal decompression or fusion.

What physical therapy exercises help lumbar spondylosis?

Physical therapists prescribe core strengthening exercises like planks, bridges, and bird dogs, along with stretches for tight muscles pulling on the lumbar vertebrae. They also provide pain modalities and joint mobilization techniques for relief.

How can someone prevent the progression of spondylosis?

Preventative measures involve building up lumbar extensor muscles, maintaining ideal weight to avoid mechanical overload, utilizing proper movement patterns to lift/bend, correcting posture with a back brace if needed, and promptly treating acute back injuries before they worsen.

References

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Spondylolysis. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/10303-spondylolysis

- Lunardo, E. (2018, July 16). Lumbar spondylosis: Causes, symptoms, and treatment. Bel Marra Health – Breaking Health News and Health Information. https://www.belmarrahealth.com/lumbar-spondylosis-causes-symptoms-treatment/

- Lumbar Spondylosis. (n.d.). https://www.physiotherapy-treatment.com/lumbar-spondylosis.html

- Yetman, D. (2023, January 13). Overview of Lumbar Spondylitis. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/spondylitis-lumbar#diagnosis

- Linderbaum, K. (2018, July 2). 6 Best Spondylolisthesis Exercises, and 3 To Avoid. BraceAbility. https://www.braceability.com/blogs/articles/spondylolisthesis-exercises

4 Comments