Inversion Ankle Sprain

Introduction

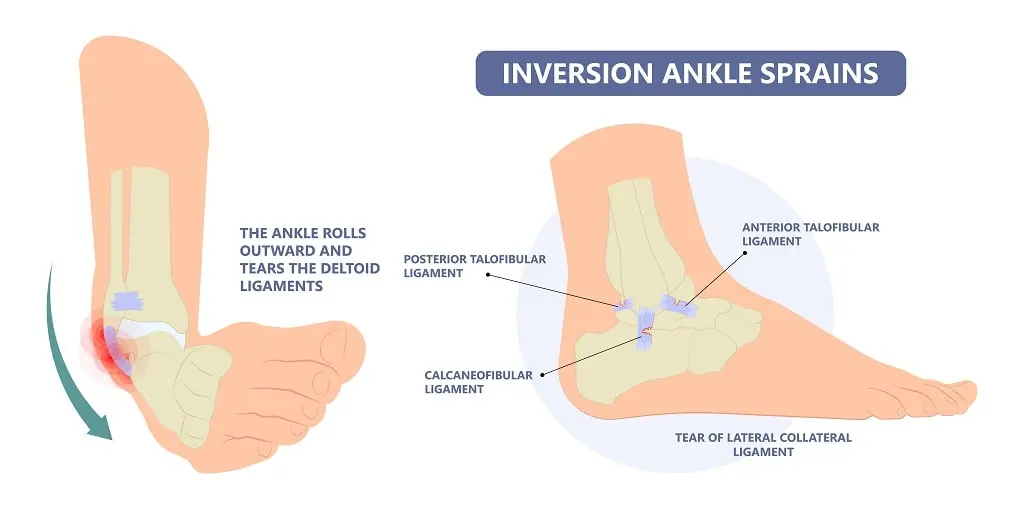

An inversion ankle sprain is a common injury that happens when your foot rolls inward, stretching or tearing the ligaments on the outside of your ankle. These ligaments are crucial for stability.

It’s often caused by activities like stepping awkwardly, landing wrong after a jump, or even just walking on uneven surfaces. Severity can range from mild (slight stretching) to severe (complete tear), with symptoms including pain, swelling, bruising, and difficulty bearing weight.

This also demonstrates that you are more likely to develop gradual degeneration and instability in the ankle with this common and troublesome issue if your initial injuries are not properly healed and treated.

A full medical history and physical examination are required for an ankle sprain injury to determine whether ligaments are sprained or torn. While rupture indicates total rupture and potential detachment, spraining signifies overstretching of ligament tissue.

It also identifies whether any related fractures or bones are broken due to the sprain. For instance, several fractures can occur, including an anterior process of the calcaneus fracture, caused by avulsion of the base of the fifth metatarsal, which is quite characteristic of the lateral ankle sprain kind.

An osteochondral defect, or compression or shearing lesion on the surface of the cartilage, can result from excessive tension on the joint caused by repetitive inversion ankle sprains. If not addressed, this can lead to the formation of an impact within the ankle joint.

The three basic ligaments are:

- The anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL)

- The calcaneo fibular ligament (CFL)

- The posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL)

- Depending on the structure of the injured ligaments, ankle sprain injuries can be classified into four grades.

Ankle Sprains: What Are They?

Tears in the ankle’s ligaments cause ankle sprains. These ligaments connect the ankle to other bones in the leg and foot or hold a portion of the ankle in place. It’s a relatively common injury that hurts.

When your ankle is sprained:

- Pain and swelling may start practically immediately.

- Ankle mobility might be challenging.

- It can be painful to put weight on the limb that has been injured.

Relevant Anatomy

Anatomy of the Ankle

Anatomy of the Ankle

The most often injured ligament in the lateral ankle ligament complex is the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL). An aggressive inversion of a plantarflexed foot results in sprain injuries to the ATFL and CFL.

For the medial side, powerful pronation and rotation movements of the hindfoot harm the strong deltoid ligament complex, which is made up of the posterior Tibiotalar (PTTL), Tibiocalcaneal (TCL), Tibionavicular (TNL), and anterior Tibiotalar Ligaments (ATTL).

The distal stabilizing ligaments. These consist of the anterior-inferior, posterior-inferior, and transverse tibiofibular ligaments; the inferior transverse ligament; and the membrane between the bones and ligament. Ankle dorsiflexion combined with external rotation of the leg results in a syndesmotic (high ankle) sprain.

With sprains being the most frequent injury kind, the ankle joint is the second most likely to get injured while participating in sports. Adult females are more likely than males and children to experience an ankle sprain, while acute medial and syndesmotic ankle fractures are uncommon.

Ankle sprains cost about a billion dollars in total in the United States of America. Ankle sprains are most common in basketball and other indoor sports, with a risk of 7 per 1,000 total exposures. Basketball players frequently sustain severe ankle sprains, and over 70% of these players experience recurrence.

Ankle injuries occurred at a rate of 3.85 per 1000 participations, resulting in 37 athletes missing 81.5 weeks of play, according to a study on professional Australian basketball players. Athletes who have chronic ankle instability perform below their potential, miss practices and events, and require regular therapy to keep active.

Mechanism of Injury

The most common cause of lateral ankle sprains is an acute change in the center of gravity of the body over the point of impact or weight-bearing foot. The lateral muscles bend and strain as the ankle shifts outward and the foot rotates inward. After being injured or overstretched, a ligament rarely returns to its previous suppleness and endurance. According to several studies, there are instances where an early return to play compromises adequate ligamentous recovery. According to reports, the more plantar flexion there is, the more likely it is that a sprain will occur.

Ankle sprains were 80.6% more likely to occur in 94 young, competitive basketball and volleyball players from Brazil if their dominant lower leg was on the left, their peroneus brevis electromyographic response time was more than 80 ms, they wore shoes without dampers, and they played certain positions.

Additionally, an epidemiological study on unilateral ankle sprains shows that the limb that dominates is 2.4 times more prone to sprains than the non-dominant leg. An active inversion action at the ankle is a less common mechanism of injury that tears the strong deltoid ligament.

Classification of Ankle Sprain

Several grading systems can be used for classifying ankle sprains, and each has benefits as well as disadvantages of its own. To ensure effective continuity of care, therapists use strategies tailored to the patient’s circumstances and educational background.

Following the examination, your physician will determine the severity of your sprain to help you create a treatment strategy. Depending on how severe the ligament damage is, sprains are categorized.

Classification of Ankle Sprain

Classification of Ankle Sprain

Grade 1

- Ankle bruising, swelling, and mild soreness

- Typically, no pain with weightbearing

- No instability on examination

Grade 2

- Partial tearing of the ligament

- Moderate ankle pain, bruising, and edema

- Mild pain with weightbearing

- Slight instability on examination

Grade 3

- Complete tear of the ligament

- Ankle bruising, edema, and extreme tenderness

- Severe pain with weightbearing

- Substantial instability on examination

Which kinds of ankle sprains are there?

Ankle sprains come in two varieties:

- Ankle sprains caused by eversion happen when the ankle slides outward, rupturing the deltoid ligaments.

- An inversion ankle injury arises when you twist your foot upward, causing your ankle to slide inward.

- The collection of ligaments that prevent your foot from rolling outward is harmed by medial ankle sprains.

- This specific type of ankle sprain is brought on by a strong upward motion of the foot and ankle.

Causes

Ankle sprains are frequently caused by the following:

- Wearing shoes that are inappropriate for your sport. You run the risk of falling or perhaps spraining your ankle doing this.

- Putting the ligament under excessive strain. Walking or jogging on an uneven path, driving your foot, or having an atypical ankle twist could all cause this.

- Running, jumping, climbing, and kicking are examples of high-impact sports that can cause ankle sprains.

Ankle or foot bending injuries have been frequently reported by patients. You can feel an impact if the ligaments are severely cut. Sprains can occur suddenly during several activities, such as:

- Walking or exercising on uneven surfaces

- Tripping or falling.

Symptoms

The pain may be bothersome or so severe that it prevents you from bearing any weight on your affected foot. Bruises are one indication of a twisted ankle. Furthermore, the ankle could feel warm to the touch.

When you go to the doctor for treatment of an ankle sprain, they will check your ankle. Additionally, he or she will check for additional wounds, such as broken skin, in the surrounding areas.

- Pain, particularly while using the affected foot to bear weight

- Tenderness upon palpation of the ankle joint

- Bruising, oedema, and swelling

- Reduced joint motion and instability. Complaints of cold foot or paresthesia could imply neurovascular compromise of the peroneal nerve.

- Previous history of ankle injuries or instability

- Special Tests: based on the structures involved, positive findings in the Squeeze Test, Talar Tilt, or Anterior Drawer

Diagnosis

Physical Examination

Once your foot and ankle have been examined closely and the event has been discussed, your doctor will diagnose you with an ankle sprain. This physical examination, which can be uncomfortable due to the swelling and inflammation, frequently consists of:

On Observation

- Several symptoms, mainly pain, swelling, and sensitivity around the ankle, especially on the lateral (outside) side, are indicative of ankle sprains, especially inversion sprains. Additionally, there may be apparent bruises and a restricted range of motion. To evaluate the extent of the damage and find any further potential ailments, the doctor will look for these symptoms on the ankle and may conduct tests. The damaged ligaments of the sprained ankle are frequently swollen and bruised.

Palpation.

- The region just above the torn ligaments is sometimes the only location that is sensitive. To identify the affected ligaments, your doctor will apply light pressure to the ankle.

Range of motion testing

- Although the doctor may move your ankle in various directions, a tight, swollen ankle may be challenging to move. If you have pain in your foot and ankle bones or have problems bearing your weight, more testing could be necessary to rule out a fracture.

An extensive examination of the foot and ankle is recommended since an ankle sprain impacts multiple structures. To evaluate the injured ankle, the patient’s medical history must be reviewed to identify any prior injuries that may be comparable. The patient’s posture and walking pattern should subsequently be closely monitored for any abnormalities, and any malalignments, atrophy, oedema, or ecchymosis should be noted. To check for any soreness over ligaments, muscles, or bony prominences, the affected structures must be palpated. It’s also essential to evaluate the patient’s active and passive range of motion.

Imaging Tests

A medical professional’s examination, symptoms, and the manner of the injury all play a major role in the clinical diagnosis of an ankle sprain. Imaging tests, such as MRI scans and X-rays, are sometimes acquired to rule out a fracture or other damage to the surrounding cartilage and tendons.

X-ray-of-Inversion-Ankle-Sprain

X-ray-of-Inversion-Ankle-Sprain

- X-rays. It can be challenging to tell severe ankle sprains from fractures because they can present with symptoms that are identical in terms of pain, bruising, and edema. Your doctor might prescribe stress X-rays in addition to standard X-rays. These images originate as the ankle is slowly pulled in different directions. Using stress X-rays can assist in determining whether the ankle’s instability is due to ligament damage.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. Ankle sprains can be diagnosed without an MRI scan. Your physician might get an MRI to assess additional ankle structures, including tendons and cartilage.

Special Tests

- Anterior Drawer Test

- Talar Tilt Test

- Posterior Drawer test.

- The squeeze test.

- External rotation stress test (Kleiger’s test)

Anterior drawer test

In a supine posture, the patient’s knee joint is flexed, the ankle joint is maintained at 10-15° of plantarflexion, and the upper leg is supported by the table. The patient’s foot rests on the front part of your forearm; then, grab the heel. With one hand, hold the patient’s tibia back while lifting the foot anteriorly.

A positive test could result in depression on the anterolateral part of the talus, and you would feel more anterior translation compared to the unaffected ankle.

Talar tilt

- Three separate areas are used for testing the ankle’s lateral ligaments. Evaluation of the calcaneofibular ligament, anterior talofibular ligament, and posterior talofibular ligament is thus made possible. The fourth step of the exam is to examine the deltoid ligament complex on the medial side of the ankle.

- Your patient should sit with his knee hanging off the table while you conduct the test. To test the anterior talofibular ligament (aTFL), place your patient’s foot in plantarflexion such that it is perpendicular to the action you’re trying to do. Use your calcaneus to perform inversion after that.

- To evaluate the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL), place your patient’s foot in the ideal anatomical position where it is perpendicular to the talus’s long axis. The foot should then be caused into eversion and inversion. The eversion section of this test causes tension on the medial portion of the deltoid ligament complex.

- If the patient expresses pain or if you notice considerable gapping in comparison to the unaffected side, this test in various positions is considered positive.

To examine the Posterior Talofibular Ligament, perform the Posterior Drawer test. The knee that has to be examined is bent to around 90 degrees while the patient is lying down. With the thumbs resting on the tibial tuberosity, the examiner grasps the proximal lower leg roughly at the tibial plateau or joint line. Next, the examiner switches the lower leg from behind. If there is no visible posterior translation or end feel, the test will be successful.

Proprioception

Starting with a straightforward single-leg stance, proprioception can be evaluated in a variety of progressively more challenging methods. To give the therapist a sense of what normal is, the patient can try it on the normal side first. Then, they can try it on the injured side.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made using the examination results and the trauma history. Ultrasound can be used in conjunction with examination to determine whether a tendon injury has occurred. Diagnostic imaging can be performed to confirm the diagnosis in chronic instances when the Ottawa Ankle Rules do not apply.

According to 27 studies involving 15,581 participants, the Ottawa Ankle Clinical Prediction Rules are a reliable method for reducing the amount of needless radiographs and ruling out fractures within the first week following an ankle injury.

- Ankle Fractures: Because they cause similar pain, swelling, and bruising, fractures, especially those of the fibula, might be confused with a serious sprain. To rule out a fracture, X-rays are necessary.

- Tendon Ruptures: In extreme situations, injuries such as peroneal tendon rips or Achilles tendon ruptures might resemble ankle sprains. Imaging and maybe a physical examination are essential for diagnosis.

- Other Ligament Injuries: Although the lateral ligaments (anterior, calcaneofibular, and posterior talofibular) are frequently involved in inversion sprains, other ligaments may also sustain injuries, such as the tibiofibular syndesmosis (high ankle sprain) or the deltoid ligament (eversion sprain).

- They can lead to pain and instability, frequently following an inversion injury. MRI is used for making diagnoses.

- Peroneal Tendon Impingement or Subluxation: This can result in pain and snapping sounds as the peroneal tendons catch or slip out of their groove. Through physical examination and palpation, this can be identified as a sprain.

- Intra-articular Menisci Lesions (Impingement Syndrome): Following an inversion sprain, these tiny cartilage lesions in the ankle joint may hurt and pop or click.

- Neuromuscular disorders: Ankle pain and weakness may be caused by neuromuscular disorders, which should be taken into consideration when there is no obvious source of injury.

- Superficial Peroneal Nerve Neuralgia: Pain and numbness, especially around the outer ankle, can be caused by irritation or entrapment of the nerves.

Other differential diagnoses to evaluate are:

- Impingement

- Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

- Sinus Tarsi Syndrome

- Cartilage or osteochondral injuries

- Peroneal Tendinopathy or subluxation

- Posterior Tibial Tendon Dysfunction

Treatment

Ankle sprains, particularly in athletes, can be effectively treated with physical therapy. Given the various stages of tissue recovery, athletes must have a varied course of therapy for acute or moderate injuries (lasting up to four weeks) as opposed to injuries that continue longer than four weeks, or those that are more severe or chronic.

Physical treatment

Physical treatment for a moderate ankle sprain aims to reduce pain and swelling while protecting the joint and its ligaments from additional harm. Physical treatment for a persistent ankle sprain aims to restore functional movement and stability while also lowering pain and oedema.

Reduce pain and swelling.

- When managing an acute lateral ligament injury, the RICE protocol (rest, ice, compression, and elevation) should be followed to reduce pain and swelling within the first 48 to 72 hours.

- If weight bearing (WB) is extremely painful, the patient can use elbow crutches and remain non-weight bearing (NWB) for 24 hours. To avoid pain and swelling, it is essential to start at least partial weight bearing (PWB) as soon as possible and to follow a normal heel-toe gait pattern.

- Light soft tissue massage and light stretches can be used to help with oedema removal as long as they do not cause pain.

In phases two and three of recovery, proprioception (balance), strength, and flexibility are enhanced by rehabilitation exercises.

- Early motion. Your physician or physical therapist will prescribe range-of-motion exercises or controlled, resistance-free ankle motions to help you avoid stiffness.

Ankle-foot exercise

Ankle-foot exercise

- Strengthening exercises. Exercises to strengthen the dynamic stabilizers (muscles and tendons) at the front and rear of your leg and ankle will be included in your treatment regimen after the pain and swelling have subsided. If weight-bearing strengthening exercises, such as toe-raising, hurt too much, you can try water exercises. Resistance-training exercises are added as tolerated.

- Proprioception (balance) training. Constant sprains and ankle instability are usually the result of poor balance. Standing on the affected foot, raising the other foot, and closing your eyes is a great way to practice balance. During this phase of rehabilitation, balance boards are frequently utilized.

Ankle-InversionEversion with TheraBand

Ankle-InversionEversion with TheraBand

- Exercises for agility and endurance. Other workouts, such as agility drills, can be incorporated gradually after you are pain-free. Agility and calf and ankle strength are greatly enhanced by running in increasingly smaller figures-of-8. As balance improves with time, the objective is to enhance strength and range of motion.

Some methods indicate that only minimal intervention is required for first-time lateral ligament sprains, which can be harmless injuries that heal fast. The 2016 NICE guidelines suggest analgesia and advise rather than regular referrals to physiotherapy. This strategy has been questioned because of the high recurrence rate and the recommendations’ lack of recommendations for rehabilitation.

- Phase 1: The reconstruction or maturation phase.

- Phase 2: The proliferation phase.

- Phase 3: The inflammatory phase.

The healing process starts with the inflammatory phase. It often lasts two to four days and begins immediately following an accident. At that stage, supporting the foot to decrease pain and oedema is the main goal. The PRICE protocol, which includes resting following the injury, applying ice at 15-minute intervals, preserving the ankle from further injury, applying a compression bandage to minimize swelling and oedema. To reduce swelling, the ankle is raised during this stage.

The exact physiological reactions to ice administration have not been thoroughly established, despite its extensive therapeutic use. Furthermore, there are very varied justifications for using it at various phases of rehabilitation. It is impossible to evaluate the relative efficacy of RICE therapy for acute ankle sprains in adults due to the lack of information from randomized controlled trials. There isn’t any evidence, nevertheless, that the RICE protocol is incorrect.

The foot and ankle are mobilized both actively and passively to increase ankle stability, decrease pain, avoid venous stasis, and enhance local circulation, which permits oedema resorption and supports the ankle joint throughout the inflammatory phase. These mobilization strategies include medial subtalar glide to increase eversion and inversion, lateral subtalar glide to increase eversion, and subtalar distraction to decrease pain.

Phase 1

- Include a brief period of rest, immobilization, and ice application to minimize swelling.

- During this stage, early weightbearing as permitted is usually advised.

- Casts or braces for 10 to 14 days may be necessary for grade 3 sprains.

- Usually, the pain and swelling go away in between two and three days. During this time, walking could be challenging, and your doctor might advise using crutches if necessary.

Phase 2

- Usually starts early and consists of functional rehabilitation with an emphasis on:

- Exercises for range of motion

- Strengthening isometrically

- Exercises for retraining proprioception, or balance

- To prevent stiffness, it’s critical to stop ankle immobilization at this stage.

Phase 3

- Exercises for strengthening and proprioception are improved, and pre-injury activities are progressively resumed. This starts with activities that don’t involve twisting or rotating the ankle, and then moves on to sports like football, basketball, or tennis that call for quick, sharp twists.

- Ankle bracing or tape may be necessary for an early return to athletic and occupational activity.

The duration of this three-phase treatment approach can range from two weeks for minor sprains to up to six or twelve weeks for more severe injuries.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment for ankle sprains is rare.

- The only injuries that warrant surgery are those that do not improve with nonsurgical care or that still cause ankle pain and instability after months of rehabilitation and nonsurgical treatment.

- For certain high ankle sprains that cause instability of the ankle syndesmosis, surgery may also be necessary.

- If a severe ankle sprain is accompanied by other problems, such as a ruptured tendon or damage to the ankle cartilage, surgery may be advised.

Types of surgery

- Arthroscopy. During an arthroscopy, your doctor looks into your ankle joint using a tiny camera known as an arthroscope. Any loose pieces of bone or cartilage, as well as any ligament segments that might be stuck in the joint, are removed using tiny tools.

- Repair/reconstruction. Your doctor might be able to use sutures or stitches to fix the damaged ligament. In certain instances, they will replace the injured ligament with a tissue transplant taken from other tendons and/or ligaments in the foot and ankle region.

Home remedies

- Unfortunately, these more established methods ignore the subacute and chronic phases of tissue healing in favor of acute therapy. It includes the range of rehabilitation from immediate attention (PEACE) to follow-up therapy (LOVE). Although anti-inflammatory drugs have been shown to improve pain and function, their usage raises concerns about possible negative effects on the best possible tissue repair. They might not be part of the routine care of soft-tissue injuries, according to certain theories.

- R-Rest.

- I-Ice.

- C-Compression, which can be achieved by bracing, taping, or applying an elastic bandage.

- E-Elevation.

For both athletes and non-athletes, further ankle sprain remedies could be:

- Acetaminophen and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines (NSAIDs) are examples of over-the-counter analgesics.

- Exercises for balancing, stretching, and strengthening.

If you were injured while participating in a sport, find out what caused the injury. Wear the appropriate footwear for your sport and inspect the field or floor before you play.

- P-Protection: After an accident, stay still and let the damaged tissue unloaded for one to three days. Preventing aggravation and protecting the injury during the initial days are crucial. Be cautious and refrain from extended relaxation, as this may result in the tissue losing its strength and quality.

- E-Elevation: By encouraging the passage of interstitial fluid from the limb towards the heart, elevating the limb above the heart helps minimize swelling.

- A-Avoid anti-inflammatory drugs: The stages of inflammation are crucial to tissue healing. Avoid using cryotherapy and anti-inflammatory drugs, as they may hinder long-term tissue recovery by lowering inflammation.

- C-Compression: To reduce bleeding and edema, pressure the damaged limb with tape and bandages.

- E-Education: The patient must be taught the value of active recovery, which includes promoting pain-free movement, carrying on with everyday activities within pain thresholds, and avoiding extended periods of inactivity. Avoid passive therapies like ice and analgesics since they could impede the body’s natural healing process.

- L-Load: The ideal load should be applied to the tissue without causing more pain. This promotes tissue remodeling, healing, and tolerance so that normal activities can resume.

- O-Optimism: Prognoses and results are generally better for patients who have optimistic expectations. Loss, fear, and predicting impair the healing process.

- V-Vascularization: Painless cardiovascular exercise and timely mobilization improve body processes, make it easier to resume work, and reduce the need for pain medication.

- E-Exercise: Exercise helps restore proprioception, strength, and mobility early in an injury and lowers the likelihood of recurrence. Pain should be minimized and used as a guide to increase exercise intensity to ensure the best possible healing throughout the subacute phase of recovery.

After inflammation has been reduced, the proliferative phase starts and lasts for four to six weeks. Scar tissue starts to develop during this stage, assuming the normal tissue’s original physical characteristics. During this phase, physical therapy aims to protect the joint against recurrence of the injury while recovering ankle function, improving weight-bearing capacity on the affected foot, and expanding range of motion.

It is crucial to start ankle therapy as soon as possible. Ankle function should significantly improve after the first week of exercise. A brace or tape may also be utilized to protect the joint during the beginning of this phase. Depending on patient choice, it should be used as soon as edema subsides.

In a controlled trial with 50 patients, the results showed a significant improvement in ankle joint function at 10 days and 1 month when treating lateral ligament ankle sprains.

Complication

Ankle sprains can make it difficult to walk and perform other daily tasks if they are not properly diagnosed, treated, and cared for. You may walk unevenly if you have a sprained ankle. Because you are placing greater weight on the healthy ankle, you run a higher risk of injuring it.

Inversion ankle sprains can cause mild to severe complications, such as persistent pain, unstable joints, recurring sprains, and possibly even arthritis. In addition, severe sprains may result in problems such as osteochondral abnormalities, nerve damage, and fractures.

- Chronic Pain and Instability

- Recurrent Sprains

- Arthritis

- Fractures

- Osteochondral Defects

- Nerve Damage

Risk Factors

Several risk factors for lateral ankle sprains have been identified by studies:

- Younger age, a history of lateral ankle sprains, a high body mass index, and hip muscular weakness, particularly in the hip extensors

- Ankle muscular weakness impairs balance.

- Instead of being a risk factor for lateral ankle sprains, it has been proposed that reduced ankle eversion strength may be a pathological consequence of chronic ankle instability and recurrent ankle sprains.

Prevention

Ankle sprains can be avoided successfully by maintaining exceptional muscle strength, flexibility, and balance. Sprains can be avoided by taking the following safety measures.

- As fatigue can raise the risk of injury, be aware of it and take pauses when necessary.

- To prepare your muscles and joints, always warm up before working out or participating in sports.

- Strengthening activities can help improve ankle stability.

Ankle Braces or Taping

These might offer additional support, particularly if you’ve experienced instability or ankle sprains in the past.

Proper Footwear

- Make sure your shoes fit properly and are suitable for the activity you’re doing. Think about wearing shoes with supportive ankles or high-tops.

- Avoid wearing high heels as much as possible because they can make inversion sprains more likely.

Outcomes

Ankle sprains typically have satisfactory results. Most people can eventually resume their normal activities after getting the proper care and therapy. Resuming activities and achieving successful results rely on:

- How severe the sprain is.

- If there are further wounds.

- Adherence to rehabilitation exercises by the patient. The most frequent reason for persistent ankle instability following a sprain is inadequate therapy. The patient will be at risk for more ankle sprains if they stop performing the strengthening exercises because the affected ligament or ligaments may deteriorate.

FAQs

How is an inverted ankle sprain treated?

It is advised to rest, apply ice, compress, and elevate (RICE) in the initial days following a trauma. Only two to seven days after the incident should be spent on analgesic therapy, with paracetamol being the preferred drug. Surgery is not as good as conservative treatment.

A grade 1 inversion ankle sprain is what?

Ankle sprains are categorized into three classes based on the force used. Grade 1: Mild pain, edema, and stiffness accompanied by ligament stretching or minor tears. Walking is typically doable with little pain because the ankle feels solid.

How can ankle inversion be improved?

Loop an exercise band around the inside of your affected foot while holding both ends in one hand. Next, apply pressure to the band with your other foot. Gently press your injured foot on the band while keeping your legs crossed to cause it to separate from your other foot. After that, slowly unwind.

Can a fracture result from inverting the ankle?

An inversion injury’s twisting motion may cause a single calcaneal fracture without any malleolar pain during examination. The ankle clinical examination includes palpating the base of the fifth metatarsal bone.

Is massaging a sprained ankle beneficial?

Is it appropriate to massage an injured ankle? According to a certain study, the answer is definitely yes: you should massage your damaged ankle. This includes a 2017 study that discovered that calf muscle massage is beneficial for increasing ankle flexibility and balance.

How can the foot’s inversion be corrected?

To alleviate some of the symptoms and make sure the ankle doesn’t sustain any further damage, the PRICE (Protection, Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation) strategy is recommended during the first 24 to 48 hours after an ankle injury. Rest: Avoid activities that make the injury worse.

Why isn’t my ankle sprain getting better?

There may be another issue if an ankle injury does not go away. Ankle sprains frequently occur in conjunction with other ailments. A more serious ankle issue, such as a fracture, torn or strained tendons, torn ligaments, or a cartilage injury, may be concealed by a sprain.

Reference

- Sprained ankle: Causes, symptoms, and treatment | UPMC. (n.d.). UPMC | Life Changing Medicine. https://www.upmc.com/services/orthopaedics/conditions/ankle-sprain

- Sprained ankle – OrthoInfo – AAOS. (n.d.). https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases–conditions/sprained-ankle/

- Ankle, C. F. &. (2024, February 13). Inversion ankle sprains – a common sports injury. Certified Foot & Ankle Specialists. https://certifiedfoot.com/inversion-ankle-sprains-athelete/

- MGH Physical Therapy Services. (n.d.). Physical therapy guidelines for lateral ankle sprain. https://www.massgeneral.org/assets/mgh/pdf/orthopaedics/foot-ankle/pt-guidelines-for-ankle-sprain.pdf