Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury

Introduction:

An Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injury is a common knee injury that occurs when the ACL, one of the major ligaments in the knee, is overstretched or torn.

The knee joint is stabilized by the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), one of two cruciate ligaments. Originating from the anteromedial aspect of the intercondylar region of the tibial plateau, this robust band of collagenous fibers and connective tissue extends posterolaterally to attach to the medial aspect of the lateral femoral condyle. Here, two significant landmarks are located: the bifurcate ridge, which divides the two ACL bundles, and the lateral intercondylar ridge, which defines the anterior boundary of the ACL. 32 mm in length and 7–12 mm in width make up the ACL. An isometric anteromedial and a posterolateral bundle with more adaptable length alterations are its two bundles.

While the posterolateral bundle is the tightest in extension and primarily provides medial-lateral and rotational stability (secondary restraint), the anteromedial bundle is the tightest in flexion and is primarily in charge of anterior tibial translation (85% of the stability).

The strength of the ACL is 2200 N. Together, the ACL and PCL create a cross inside the knee that limits the tibia’s excessive forward or backward motion in relation to the femur during flexion and extension. According to histology, type I collagen makes up 90% of the ACL, while type III collagen makes up 10%. The middle geniculate artery provides the majority of its blood supply. The posterior articular nerve is a branch of the tibial nerve that provides neurological innervation.

Definition of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury:

A tear or sprain of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), one of the powerful bands of tissue that aid in joining your femur and tibia, is known as an anterior cruciate ligament injury.

Anterior cruciate ligament injuries are more common in athletes who play sports like basketball, football, soccer, and hockey that involve high knee-jerk movements. The majority of ACL injuries happen in sports that require abrupt stops or direction changes, jumping, and landing.

One of the four ligaments essential to knee joint stability is the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). Made of strong, fibrous material, a ligament limits joint mobility to control excessive motion. The ACL is the most often injured of the knee’s four main ligaments. ACL injuries frequently cause the knee to feel as though it is “giving out.”

RICE Principle (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) may be used as part of your treatment, depending on the severity of your ACL injury. Rest for a few days, followed by rehabilitation activities to help you restore your strength and mobility. Surgery to replace the damaged ligament is the last resort.

The likelihood of ACL damage may be decreased with the right physical therapy exercise training regimen.

Anatomy of Anterior cruciate ligament:

An important component of the knee joint, the ACL is a band of thick connective tissue that runs from the femur to the tibia and resists anterior tibial translation and rotational loads.

The ACL is placed anterior to the tibia’s intercondyloid eminence and merges with the anterior horn of the medial meniscus after emerging from the posteromedial corner of the medial face of the lateral femoral condyle in the intercondylar notch. As it moves from the femur to the tibia, the ACL travels across the joint anteriorly, medially, and distally. In the process, it rotates in a little outward (lateral) spiral.

Depending on where the bundles are inserted into the tibial plateau, the ACL is divided into two parts: the larger posterolateral bundle (PLB) and the smaller anteromedial bundle (AMB). The AMB is relatively slack and the PLB is tight when the knee is extended. The AMB becomes the constraint to anterior tibial load as the knee flexes because the ACL’s femoral attachment takes on a more horizontal position, tightening the AMB and loosening the PLB.

Epidemiology:

Nearly half of all knee injuries involve the ACL, making it the most frequently damaged ligament in the knee. In the United States alone, the annual reported incidence is roughly 1 in 3500. In the United States, about 400,000 ACL repairs are performed annually. However, because there is no systematic surveillance, data could not be reliable.

Although there is no bias based on age or gender, it has been proposed that a number of factors may put women at higher risk for ACL injuries. According to reports, the female-to-male ratio in athletics is 4.5: 1. ACL tears are more common in the supporting leg of female athletes than in the kicking leg of male players, and they also occur at a younger age.

According to certain research, one of the variables raising the risk for females is that they may have weaker hamstrings (more dominant quadriceps) and preferential recruitment of the quadriceps muscle group during deceleration. Because the quadriceps muscles are less effective than the hamstring muscles at limiting anterior tibial translation, engaging them while slowing down puts excessively high loads on the ACL. In addition, women’s core stability is inferior to men’s.

Due to higher valgus angulation and knee extension, female landing biomechanics may raise the risk of ACL injury. In addition to decreased hip and knee flexion and decreased fatigue resistance, one study that used video analysis showed that female athletes are more prone to put their knees in higher valgus angulations while abruptly changing directions, which increases the load on the ACL ligament.

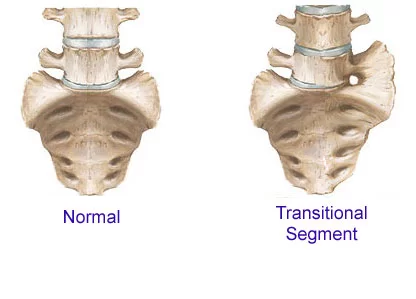

Anatomical risk factors include a higher body mass index, a smaller femoral notch, impingement on the notch, a smaller ACL, hypermobility, joint laxity, and a history of ACL damage are additional risk factors that may raise the chance of injury.

Some risk variables associated with participation in particular sports, such as basketball and soccer, were found to be associated with higher risk in males and girls, respectively.

Additionally, it has been noted that hormones, particularly during the preovulatory stage of the menstrual cycle, impact coordination. It was observed that women on OCP were less impacted. Although this is still debatable and unproven, estrogen’s effects on the strength and flexibility of tissues like ligaments may contribute to females’ vulnerability to injury. The COL5A1 gene, which produces collagen, has been linked to a decreased risk of injury in females.

Mechanism of Anterior cruciate ligament Injury:

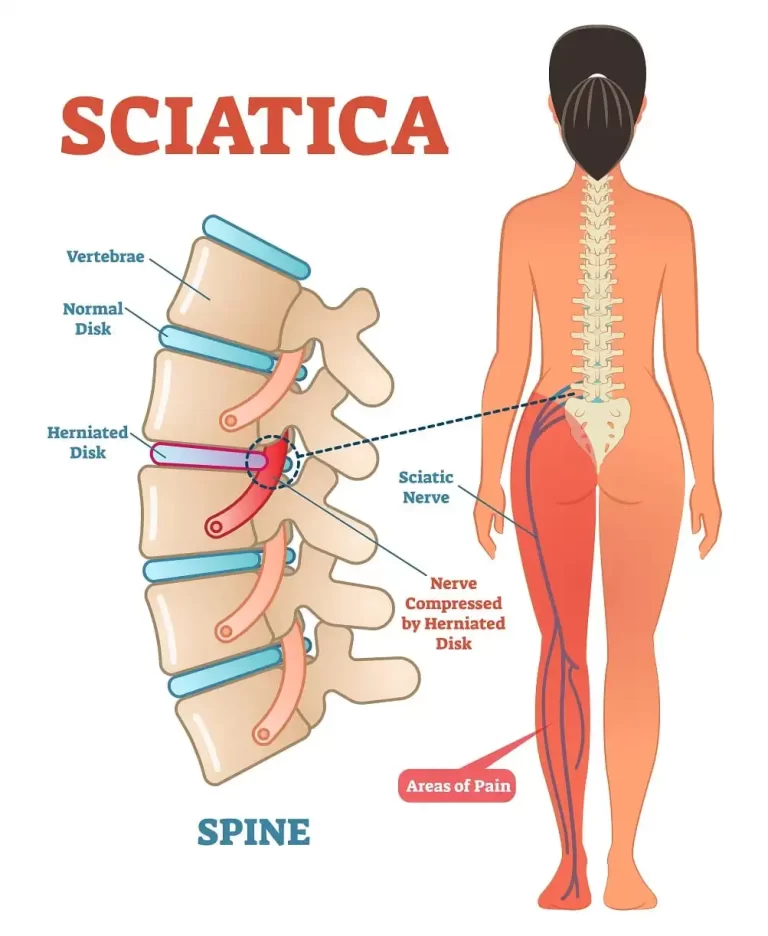

Rotational stability depends on the ACL’s capacity to withstand the movements of internal tibial rotation and anterior tibial translation. This function plays a crucial role in the pivot-shift phenomenon by preventing anterior tibial subluxation of the lateral and medial tibiofemoral joints.

It has been demonstrated that the ACL contains mechanoreceptors that can sense changes in tension, acceleration, speed, and direction of movement as well as changes in the knee joint’s location. A major contributing factor to instability following ACL injuries is decreased neuromuscular function caused by a reduction in somatosensory input. The stability of the knee in the terminal extension of the screw-home mechanism is crucial for athletes who play sports that require cutting, jumping, and quick deceleration.

Causes of Anterior cruciate ligament injury:

The majority of ACL tears in athletes happen through non-contact pivoting injuries, in which the knee is slightly flexed and in valgus, and the tibia translates anteriorly. Another injury mechanism that has been observed is a direct impact on the lateral knee. Basketball, soccer, and skiing sportsmen are the most vulnerable to non-contact injuries. Football players are the athletes most at risk for contact injuries.

Acute ACL ruptures may be linked to several intra-articular and extra-articular traumas. Meniscal tears are among them; in more than half of acute ACL tears, there is lateral meniscus damage, while in chronic situations, the medial meniscus is more affected. An ACL injury may potentially result in injuries to the PCL, LCL, and PLC. With the emergence of complex, irreparable meniscal tears and chondral injuries, chronic ACL shortage appears to harm the knee. For example, medial meniscus injury in bucket handles.

There are various methods to damage the anterior cruciate ligament:

- Shifting course rapidly

- Suddenly stopping

- Running at a slower pace

- Making a bad landing after a jump A football tackle is an example of direct contact or collision.

In several sports, female athletes are more likely than male athletes to sustain ACL damage, according to many studies. It has been suggested that variations in neuromuscular control, muscle strength, and physical conditioning are to blame. Additional hypothesized explanations include variations in the position of the pelvis and lower extremities (legs), a rise in ligament looseness, and the impact of estrogen on ligament characteristics.

Symptoms of Anterior cruciate ligament injury:

- An audible “pop” or “popping” sound comes from the knee joint.

- Severe Knee pain and inability to continue activity

- Knee swelling

- Loss of range of motion

- A sensation of unsteadiness or “giving way” when carrying weight.

Grades of Anterior cruciate ligament Injury:

- Grade 1 ACL damage: A sprain is considered a grade 1 injury. The knee joint remains stable despite little injury to the ligament.

- Grade 2 ACL injury: A partial tear with damaged and strained ligaments is known as a grade 2 ACL sprain.

- Grade 3 ACL injury: The most common kind of ACL injury is a grade 3 sprain, which is a total tear of the ligament. People who have total ACL tears usually think about having surgery to treat their injury.

Risk factor of Anterior cruciate ligament Injury:

Your risk of suffering an ACL injury is increased by several factors, such as:

- Being a woman, perhaps as a result of anatomical variations, hormonal impacts, and muscle strength

- Engaging in specific sports, like football, basketball, gymnastics, soccer, and downhill skiing

- Inadequate conditioning.

- Putting on shoes that are too small.

- Using sports equipment that hasn’t been properly maintained, like improperly fitted ski bindings

- Using artificial turf for play.

External Risk Factors:

- Competition in games versus practice: The impact of competition type on the likelihood of an ACL injury in athletes is mostly unknown. Athletes are more likely to have an ACL injury during a game than during practice, according to Myklebust. This research raises the possibility that an athlete’s likelihood of sustaining an ACL injury is influenced by their level of competition, their style of competition, or a combination of the two.

- Footwear and playing surface: Increasing the coefficient of friction between the playing surface and the sports shoe may enhance traction and athletic performance, but it may also raise the chance of ACL injury. Lambson discovered that football players who wear boots with more cleats and a correspondingly higher torsional resistance at the foot-turf interface are more likely to get ACL damage. According to Olsen, female team handball players who play on artificial floors with higher torsional resistance at the foot-floor interface are more likely to have an ACL injury than those who play on wood floors. For male players, this relationship did not exist.

- Protective equipment: The application of functional bracing to protect the ACL-deficient knee is a topic of some debate. In his study of professional skiers with ACL-deficient knees, Kocher discovered that individuals who did not wear a functioning brace had a higher chance of suffering a knee injury than those who did. McDevitt conducted randomized controlled research on the use of functional braces in cadets undergoing ACL surgery at US military schools. The rate of ACL graft re-injury was unaffected by the use of functional bracing at the 1-year follow-up. However, there were two injuries in the braced group and just three in the unbraced group.

- Meteorological conditions: The mechanical interaction between the foot and the playing surface in sports performed on artificial or natural turf is greatly influenced by the weather. The impact of these factors on an athlete’s chance of sustaining an ACL injury, however, is little understood. Orchard found that times with high evaporation and little rainfall were associated with a higher incidence of non-contact ACL injuries from Australian football. This study presents the theory that the mechanical interface (or traction) between the shoe and the playing field is directly impacted by weather and that this directly affects the chance of an athlete sustaining an ACL injury.

Internal Risk Factors

- Anatomical risk factors: By leading to elevated ACL strain values, abnormal posture and lower extremity alignment (hip, knee, and ankle, for example) may put a person at risk for ACL damage. Therefore, while evaluating risk factors for ACL damage, alignment of the entire lower extremity should be taken into account. Regretfully, not much research has examined lower extremity alignment as a whole and established its relationship to ACL injury risk. The majority of the knowledge has been derived from studies of particular anatomical measurements.

- Bony morphology: According to recent studies, a tibial plateau slope of ≥ 12° was linked to a higher chance of developing contralateral ACL injury following ACL repair as well as a risk of lateral meniscus tear. The steeper the tibial plateau, the greater the risk of ACL injury. Another risk factor for ACL injuries is the depth of the distal femoral condyle, which can be linked to changes in the pressure points between the tibia and femur as well as rotatory knee laxity.

Differential Diagnosis:

- ACL tear

- Epiphyseal fracture of femur or tibia

- Medial collateral knee ligament injury

- Meniscal tear

- Osteochondral fracture

- Patellar dislocation

- Posterior cruciate ligament injury

- Tibial spine fracture

Diagnosis of Anterior cruciate ligament Injury:

- X-rays: To rule out a bone fracture, X-rays might be required. However, soft structures like ligaments and tendons are not visible on X-rays.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): An MRI produces images of your body’s soft and hard tissues by using radio waves and a powerful magnetic field. The amount of an ACL injury and indications of harm to other knee tissues, such as the cartilage, can be seen on an MRI.

- Ultrasound: Ultrasound is a technique that uses sound waves to see interior structures. It can be used to check for damage in the knee’s ligaments, tendons, and muscles.

Special Test:

Anterior Drawer Test:

To take the test, you must lie on your back with your knee bent. Just behind your knee, someone else grabs your tibia and gently draws you forward. An ACL tear may be suspected if your tibia moves excessively beneath your femur, which is a sign of a positive test.

When doing the anterior drawer test, the patient lies supine with the foot planted and the affected knee flexed to 90 degrees. The doctor may find it simpler to stabilize the patient’s foot by sitting on it. Using both hands, the physician will grasp the proximal tibia and draw it forward. If the tibia is excessively anteriorly translated in relation to the femur, the test is positive. Comparing to the unaffected knee may also be useful because patients may have greater ACL laxity that is not pathologic. This test may detect chronic injuries but not acute ones, with a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 91%.

The Lachman test:

With 95% sensitivity and 94% specificity, the Lachman test is the most sensitive method for evaluating ACL rupture. The patient is placed in a supine position and their knee is bent about 30 degrees for the test. The physician should move the tibia forward with one hand while stabilizing the distal femur with the other. Increased anterior tibial translation about the femur indicates a positive test result.

The test result can be interpreted as either no endpoint (ACL rupture) or firm endpoint (intact ACL). The degree of anterior tibial translation, measured in millimeters, is used to classify the grade of ACL rupture. Grade 1 translation is 3-5 mm, Grade 2 translation is 5-10 mm, and Grade 3 translation is > 10 mm. The good side should always be compared with the wounded side, though. The doctor should also know that a PCL tear might translate the tibia from a posteriorly subluxated posture, which could lead to a “false” Lachman test interpretation.

The pivot shift test replicates the real giving way event that occurs in knees with an ACL deficiency. Internally twisting the tibia while putting valgus force on the knee and bringing it from extension to flexion is how the test is carried out. Iliotibial band (ITB) strain causes the anteriorly subluxated tibia to clunk at 20–30 degrees of flexion during knee extension.

ITB and MCL integrity, as well as the lack of knee flexion contracture, are requirements for the test. Patients who are guarding may find this test challenging to do, and some may refuse to let the clinician administer it. When positive, this test is very specific (98%) but insensitive (24%), as evaluation is challenging because of patient pain and compliance.

The lever sign test: is carried out by pressing down on the quadriceps (distal thigh) while holding a fulcrum (such as the examiner’s fist) beneath the proximal portion of the supine patient’s calf. Whether or not the ACL is intact determines how the test is interpreted; the patient’s heel will either rise off the examination couch or stay down.

Treatment for anterior cruciate ligament injury:

ACL care ought to be customized for each patient. Treatments that are non-surgical or operational are both acceptable. When choosing how to treat an ACL, a number of aspects should be taken into account, such as the patient’s age and demands, activity level, involvement in sports, and the condition of other supporting and stabilizing structures.

The “RICE” therapy, which entails rest, ice, compression of the injured knee, and elevation of the injured lower extremity, is the acute treatment. Patients may use a wheelchair or crutches if needed, but they should not bear any weight. Although over-the-counter drugs like NSAIDs can be used to relieve pain, the treating physician usually has the final say in the matter.

Medical Treatment:

- Pain and swelling can be lessened with the use of anti-inflammatory medications.

- Knee brace: When running or participating in sports, some individuals with ACL damage can benefit from wearing a brace on their knee. It offers further assistance.

- Put a steroid injection into your knee.

Surgical Treatment:

ACL Reconstruction:

Your injured ligament will be removed by your surgeon, and a tendon segment will be used in its place. This substitute tissue, known as a graft, is taken from a deceased donor’s tendon or another area of your knee.

To precisely place the graft, your surgeon will drill holes or tunnels into your thighbone and shinbone. The graft will then be fastened to your bones using screws or other fixation tools. The graft will act as a support structure for the growth of new ligament tissue.

This is recommended for younger active or older active (>40 years) high-demand patients who have a full ACL rupture. Restoring anterior and rotational stability by an anatomical ACL repair is the main goal to reduce the likelihood of subsequent meniscal or chondral problems. To lower the risk of postoperative arthrofibrosis, patients must be rehabilitated to attain a complete range of motion before surgery. Activity limitation is unrealistic, even though it is suggested in the pediatric population. Reconstruction would also be indicated by a partial ACL rupture accompanied by functional instability. Resuming sports engagement after rehabilitation is heavily influenced by several functional, psychological, and demographic aspects.

Surgical technique: arthroscopically aided; the graft bed is prepared by either leaving the stump as a guide for tunnel location and healing augmentation, or by fully clearing the native ACL remnants. There are no known differences between these methods. Furthermore, no variations in results between single-bundle and double-bundle reconstructions have been documented. The most widely used method is still single bundle reconstruction. A double-bundle reconstruction could result in more stable native knee kinematics.

Tunnel Placement

Femur side: transtibial or tibia-independent, using an outside-in or inside-out approach. In the sagittal plane, the tunnel should ideally be positioned between one and two millimeters from the posterior femoral cortex. The goal is to diminish rotational laxity in the coronal plane by positioning a more horizontal graft. Therefore, the graft should be placed at two o’clock for the left knee or ten o’clock for the right knee utilizing the clock face of the lateral wall. The appropriate placement of the femoral tunnel should be facilitated by the use of anteromedial and far medial drilling ports. Posterior wall blowout can be prevented by drilling in more than 70 degrees of flexion.

Tibia side: Sagittally, a final, appropriate tunnel location would be guided by multiple landmarks. The center of the tunnel should be 9 mm posterior to the anterior inter-meniscal ligament, 6 mm anterior to the median eminence, and 10 to 11 mm anterior to the anterior border of the PCL. In the coronal plane, the tunnel’s trajectory should be less than 75 degrees from the horizontal. Adjusting the tibia beginning point halfway between the posterior medial edge of the tibia and the tibial tubercle will help with this.

Graft placement and fixation: Up to 50% of the stress relaxation can be decreased by preconditioning the graft. There are no clinical effects of tensioning at 20 or 40 N on results. The ideal flexion angle for the transplant is between 20 and 30 degrees. Several fixation options can be used separately or in combination. Interference screws can be used for aperture or compression fixation, while cortical buttons, screws, washer posts, or staple fixation can be used for suspensory fixation.

Physical Therapy Treatment:

Use of RICE Principles:

- Rest: In order to reduce pain, rest is essential. Your symptoms will worsen if you move your knees.

- Ice Pack: Try applying 20 minutes of ice to your knee every two hours while you’re awake.

- Compression: Encircle your knee with an elastic bandage or compression wrap.

- Elevation: Prop your knee up on pillows while lying down.

Ultrasound Therapy:

By creating vibrations in the soft tissue and raising the temperature inside the tissue, ultrasound, and electrotherapy for ACL rehabilitation improve blood flow and lessen pain. Additionally, the heat generated relaxes muscles and enhances soft tissue elasticity.

TENS (Transcutaneous Electrical Stimulation):

TENS works in two ways: first, it stimulates the body in a way that differs from how it would react to pain; second, it artificially causes the muscle to contract, interrupting the spasm cycle. According to research, electrical stimulation and exercise after ACL restoration improved knee range of motion in both flexion and extension.

Low-Level Laser Therapy (LLLT):

LLLT promotes tissue healing by lowering pain and swelling by penetrating the tissue with short wavelengths of light (600–1000 nm). Results from a study that was published in Photomedicine and Laser Surgery indicated that LLLT enhanced the medial ligament’s tensile strength and recovery.

Whirlpool therapy, a type of hydrotherapy, can help with pain management and range of motion after the incisions from the ACL surgery have healed. Knee range of motion exercises can be facilitated by placing the patient in a cold whirlpool.

Exercises for Anterior cruciate ligament injury:

Quad setting exercises:

- Place a little towel beneath your knee while lying on your back. Press the back of your knee onto the towel to tighten your quadriceps.

Short arc quads (SAQ):

- Place a ball beneath your knee while lying on your back. Maintaining the back of your knee against the ball, fully extend your knee.

Straight leg raises:

- Slowly raise your straight leg 12 to 15 inches by contracting the quadriceps muscle on top of your thigh. After two seconds of holding, carefully drop your leg.

Heel slides:

- While you are lying on your back, softly bend your leg and bring your heel up to your buttocks.

Prone knee bends:

- Using your hamstring on the back of your thigh, carefully bend your damaged knee up while lying on your stomach.

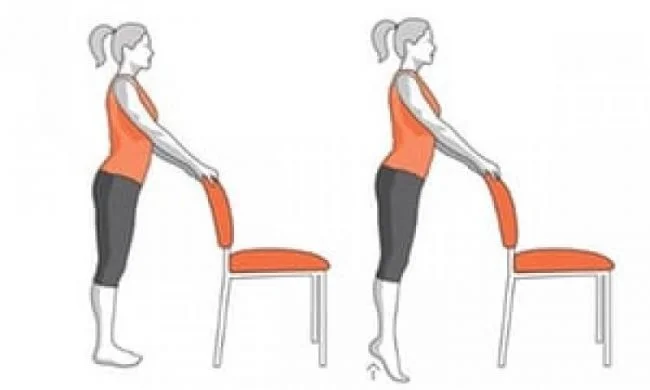

Heel raises:

- Standing is required for heel lifts. For balance, start by resting one hand on the back of a chair. Now, while standing on your tiptoes, carefully raise the heel of your affected leg. For five to ten seconds, remain there. Reduce your heels gradually. Do this ten times.

After Surgery : (Post Operative Rehabilitation)

First Week: 1

To lessen swelling, elevation and frequent ice are applied. By the end of the first week, complete extension and 70 degrees of flexion are the desired results. Crutches and the usage of a knee brace are essential.

For a minimum of eight weeks, multidirectional patella mobilizations should be incorporated. During the first four weeks, additional mobilization exercises include passive knee extension (without hyperextension) and passive and active mobilization in the direction of flexion. Exercises that strengthen the quadriceps (vastus medialis), hamstrings, and calf muscles can be done.

Week 3-4:

To walk with one crutch, the patient must make a sincere effort to increase the stance phase. Crutch use can be decreased sooner with strong hamstring and quadriceps control.

Week 5:

The knee brace’s usage is gradually decreased. Although flexion should not yet be complete, passive mobilizations should restore motility. Close-chain exercises are a good place to start for hamstring and quadriceps (vastus medialis) exercises. Start the exercises at a low intensity (50 percent of maximum force) and work your way up to 60 to 70 percent. Leg presses, steps, and other less responsible postures should be the foundation for the closed chain workouts, which should progress to more crowded starting positions like the squat. Control of the quadriceps, pain, and edema determine how well the workout goes.

If the overall strength is good, proprioception and coordination training can begin. This incorporates toll and board balancing exercises.

Week 10:

Isokinetic workouts and dynamic forward, backward, and lateral motions can be incorporated.

After Month 3:

The patient can progress to functional exercises like jogging and leaping after three months. Exercises for coordination and proprioception are becoming

It is possible to make heavier, faster direction shifts. Exercises should be improved by diversity in visible input, surface stability, exercise speed, task complexity, resistance, one- or two-legged performance, etc. in order to promote coordination and control through afferent and efferent information processing.

Month 4-5:

The ultimate objective is to increase the knee stabilizers’ strength and endurance, enhance neuromuscular control through plyometric activities, and incorporate sport-specific workouts. In order to prevent fresh injuries during competition, autokinetic reflexes are improved by acceleration and deceleration, variations in running, and turning and cutting maneuvers.

Return to Activities:

It is advised that the patient safely engage the brake in a mock emergency before getting behind the wheel again. This usually occurs one to three weeks following left-sided ACLR and four to six weeks following right-sided ACLR.

It is advised that patients achieve 95% knee flexion range of motion (ROM), full extension ROM, and no effusion or trace of effusion before starting to run again. pain-free repetitive single-leg hopping (also known as “pogos”), pain-free water jogging, pain-free alter-G running, and no limb symmetry index (LSI)>80% for quadriceps strength.

DO’S & DON’TS for Anterior cruciate ligament injury:

- Rest a lot because your body will need all the energy it can obtain to heal the injured knee tissues. During the first few weeks following surgery, when healing is occurring at its quickest rate, take it easy and avoid standing up as much as possible.

- Use cryotherapy: It has been demonstrated that cold therapy can help lessen the pain and swelling following knee surgery. Ice your knee frequently to help reduce swelling and hasten the healing process. To maximize the benefits of cryotherapy, employ an active cold therapy device if at all possible.

- Apply compression therapy: Compression bandages and contemporary active compression therapy devices aid in the removal of extra fluid from the knee joint’s surrounding tissue, hastening the healing process.

- See a physical therapist on a regular basis to learn the stretching and strengthening techniques that will speed up your recovery and help you avoid being hurt again.

- Avoid doing too much too soon: Your body needs more time to heal completely, even though it may be tempting to get back to your regular activities as soon as possible, especially once the acute pain subsides. Pay close attention to your physical therapist’s recommendations and avoid doing more than they advise.

- Don’t miss doctor’s appointments: Follow the timetable your doctor gives you. Staying on course during your recovery is crucial, and only your physician can verify that the repairs they made are mending properly.

- Avoid stopping physical therapy too soon: Many people are tempted to stop attending physical therapy sessions before they have fully recovered because the pain goes away and you can regain a comfortable range of motion rather quickly. To guarantee that the healing process is given enough time to finish, adhere to the entire course of treatment.

Prevention of Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injury:

- Strength Training: To improve knee stability, strengthen your quadriceps, hamstrings, glutes, and core muscles.

- The right way to warm up is to do mobility and dynamic stretching exercises before engaging in any physical activity.

- Neuromuscular Training: Use plyometric workouts and agility drills to enhance proprioception, balance, and coordination.

- Jumping and Landing Techniques: To lessen the strain on the ACL, learn to land gently with your knees slightly bent and positioned over your feet.

- Avoid Sudden Pivoting or Twisting: Use the right sports methods to minimize excessive knee rotation and lateral motions.

- Footwear and Playing Surface: keep away of slick or uneven surfaces and wear shoes suitable for the sport.

- Gradual Progression: To avoid causing undue knee strain, increase exercise length and intensity gradually.

- Bracing (if required): For extra support during high-risk activities or during rehabilitation, use knee braces.

Prognosis:

ACL-deficient knees are more prone to the evolution of arthritis with subsequent damage to the chondral and meniscal structures. Restoring native knee kinematics with ACL restoration has been shown to result in a high degree of return to sports participation.

The severity, course of therapy, and recovery from an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury all affect the prognosis.

- Partial ACL Tears: Many people can regain stability and function without surgery with the right physical therapy and strengthening exercises. But the chance of getting hurt again is increased.

- Complete ACL Tears: Usually necessitate surgical reconstruction, particularly in athletes. After surgery, most patients who receive structured therapy recover well within 6 to 12 months.

- Long-term Prognosis: If left untreated, ACL injuries can result in early-onset osteoarthritis, persistent knee instability, and an elevated chance of meniscal rupture. Strength training and appropriate rehabilitation are essential for avoiding problems and regaining knee function.

Complication:

- Knee Instability: Recurrent knee buckling caused by an ACL tear raises the possibility of additional injuries.

- Meniscal Tears: Prolonged instability can put the meniscus under too much strain, which can result in tears.

- Osteoarthritis: The chance of developing early-onset knee osteoarthritis is increased by chronic joint instability and cartilage degradation.

- Decreased Range of Motion: Stiffness and the development of scar tissue can restrict knee range of motion.

- Muscle Weakness: Overall knee function may be impacted by quadriceps and hamstring weakness caused by inactivity or inadequate rehabilitation.

- Graft Failure (Post-Surgery): Graft rupture in ACL restoration may result from inadequate healing or severe strain, necessitating revision surgery.

Both intraoperative and postoperative problems can occur in many different ways. Graft tunnel mismatches, for example, in BPTB grafts, can cause the tibial bone plug to protrude and jeopardize distal fixation if they are longer than the total femoral, tibial, and intra-articular portions. This can occur with non-transtibial drilling procedures, patella Alta, and BPTB allograft. Nonetheless, it is a preventable circumstance that may be addressed by precisely measuring the tunnel and adjusting the graft appropriately, which can be done by twisting the graft to make it shorter.

Tunnel malpositioning: sustained rotational instability would be caused by a vertical tunnel in the coronal plane on the femoral side rather than a more horizontal one (positive pivot shift test). A tight knee in flexion and a loose knee in extension are the results of anterior misplacement in the sagittal plane, and vice versa for posterior misplacement. A clean view and prevention of anterior-posterior misplacement would result from clearing the resident ridge. A stiff knee in flexion and roof impingement in extension are the results of an excessively anterior misplacement on the tibial side. An ACL graft impingement on the PCL will occur from a posterior misplacement.

Another option is a posterior wall blowout. By exposing the posterior wall sufficiently and assessing the wall after drilling, this can be avoided. Additionally, this issue can be avoided by drilling the tube with 70 to 90 degrees of flexion. If the defect is small, posterior wall blowout can be controlled by redrilling with an anteriorly oriented trajectory and using the same intended fixation. Otherwise, the same tunnel might be utilized with supplemental interference screws and suspensory fixation if there is a substantial deficiency.

Graft failure resulting from a variety of other problems, like hardware failure, may be caused by insufficient fixation, such as graft screw divergence more than 30 degrees—attritional graft failure because of a narrow graft diameter (less than 8 mm). Revision surgery would be necessary if the BPTB graft’s intra-articular femoral bone plug dislodged. failure to diagnose a related bone malalignment or ligamentous damage. improper rehabilitation with activities like open-chain exercises that are excessively strenuous.

Infection and septic arthritis: S. epidermidis (coagulase-negative staph) is the most often implicated pathogen, and it occurs in less than 1% of all cases and is primarily superficial. The risk of infection may be reduced by routinely soaking grafts in vancomycin. Graft contamination during intraoperative handling or falling on the floor are risk factors for infection. Grafts that are spilled on the floor can be cleaned up by repeatedly soaking them in different antibiotic solutions; there is no known higher risk of infection.

At 2 to 14 days after surgery, patients typically exhibit the typical infection symptoms and indicators, including pain, edema, erythema, and elevated WBC. Aspiration, GM stain, and cultures are used to confirm the diagnosis. The graft should be immersed in antimicrobial solutions before insertion and fixation to manage intraoperative occurrences. Incision and drainage must be done right away for postoperative care. For at least six weeks, the graft can be kept alive with several I&Ds and antibiotics. Staph aureus is less likely to respond well to this mindset than Staph epidermidis.

The most frequent side effects after ACL restoration are stiffness and arthrofibrosis, which is mostly caused by a decreased range of motion before surgery. Patients have less patellar movement when they first arrive. Preoperative management begins with prevention and stresses the value of pre-hab to restore a complete range of motion before surgery; scheduling surgery after the edema has subsided lowers the risk of arthrofibrosis. To achieve a full range of motion after surgery, precise tunnel alignment is essential.

Cryotherapy and intensive physical therapy may be used up to 12 weeks after surgery. However, adhesion lysis and anesthesia-assisted manipulation may be necessary if the procedure is performed more than 12 weeks after the initial procedure.

Conclusion:

An ACL injury is a serious injury to the knee ligament that, if untreated, can cause instability, decreased mobility, and long-term problems. For the best recovery, an organized rehabilitation program, early management, and accurate diagnosis are essential.

Complete ACL tears frequently necessitate surgical reconstruction, especially for active people, but some moderate cases can be treated conservatively. Strength training, neuromuscular exercises, and appropriate movement skills are examples of preventive strategies that can lower the chance of injury. Most people can regain knee function and resume their everyday or athletic activities with the right care and rehabilitation.

FAQs:

Is surgery for an ACL minor or major?

Reconstructing the ACL Is a Major Surgery

General anesthetic is administered to you. You are thereby rendered unconscious during the process. Following the procedure, you will experience pain, edema, and stiffness. You might not be able to walk without crutches for two or three weeks.

How can an ACL injury be examined at home?

Although you can look for possible signs and symptoms, you cannot make a firm diagnosis of an ACL injury at home. A medical specialist is required for a proper diagnosis. See a doctor if you hear a popping sound, experience sudden pain, swelling, instability, or trouble carrying your own weight.

Can an ACL tear be healed with Ayurveda?

Although Ayurveda provides a comprehensive approach to healing, it’s crucial to remember that surgery is frequently required for full recovery from an ACL rupture, and that Ayurveda may not be a cure for the condition, particularly in severe situations. Ayurveda can, however, be used in conjunction with traditional therapies to help control pain, lower inflammation, and promote general healing.

Is it possible to massage an ACL tear?

If left untreated, this extremely painful injury can be hard to heal from. ACL injuries are among the many problems that massage treatment may aid with by easing scar tissue and lowering muscle tension.

Can someone with an ACL tear bend their knee?

Your ACL may expand so much right after a tear that you are unable to bend it. You might be able to bend your knee after the swelling goes down, but it will be weaker, less stable, and possibly painful.

How long does ACL physical therapy last?

The type of work you do and the difficulty of getting to it will determine this. After four to six weeks, you might be able to resume lighter responsibilities with less walking if your employment requires it. Returning to more physically demanding works could take up to three months.

How can the ACL be strengthened?

Press the back of your knee down to tighten the thigh muscles of the affected leg. Keep your knee straight. Raise your affected leg till your heel is around 30 centimeters (12 inches) off the ground while maintaining a straight leg and taut thigh muscles. Hold for roughly six seconds, then gradually release.

Does an ACL tear appear on an MRI?

The amount of an ACL injury and indications of harm to other knee tissues, such as the cartilage, can be seen on an MRI. ultrasound. Ultrasound, which uses sound waves to see within structures, can be used to look for damage to the knee’s ligaments, tendons, and muscles.

What is the new ACL procedure?

The body absorbs the implant within eight weeks and grows stronger new tissue to replace it. A new FDA-approved technique called bridge-enhanced ACL repair (BEAR) lets a damaged ACL recover itself without the need for transplant tissue from another area of the body.

Does touching the ACL cause pain?

ACL tears can cause severe agony, which usually starts right away. Additionally, you can experience discoloration and swelling, which usually worsen for a while before improving. Additionally, the knee may feel sensitive and warm to the touch, particularly when touched.

What’s the average recovery time for an ACL?

Although some people may recover in as little as six months, the average recovery time from an ACL tear is eight to nine months. Image courtesy of Getty Images . Many professional and amateur athletes’ careers were frequently ended by torn anterior cruciate ligaments (ACLs) in the not-too-distant past.

Can physical therapy repair an ACL tear?

By lowering pain and swelling, physical therapy for ACL tears aims to help the knee regain its range of motion and function. Stabilizing the knee and strengthening the thigh and leg muscles together are the objectives. A knee brace is frequently advised to improve knee stability as soon as feasible.

The ACL is taut when?

While the posterior cruciate ligament’s (PCL) fibers are taut at intermediate positions and maximal flexion, the majority of the ACL’s fibers are taut in maximal extension.

How is physical therapy for anterior cruciate ligament sprains handled?

Depending on the extent of your ACL injury, physical therapy treatment may involve rest and exercises to help you restore stability and strength, or surgery to repair the torn ligament followed by rehabilitation.

References

- Dhameliya, N. (2023, September 15). Anterior cruciate ligament injury (ACL), Physiotherapy exercise. Samarpan Physiotherapy Clinic. https://samarpanphysioclinic.com/anterior-cruciate-ligament-injury/

- Evans, J., Mabrouk, A., & Nielson, J. L. (2023, November 17). Anterior cruciate ligament knee injury. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499848/

- Anterior cruciate ligament tear – knee ligament injury – knee – conditions – musculoskeletal – What we treat – Physio.co.uk. (n.d.). https://www.physio.co.uk/what-we-treat/musculoskeletal/conditions/knee/knee-ligament-injury/anterior-cruciate-ligament-tear.php

2 Comments