Lateral Collateral Ligament

The Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) is a key stabilizer of the knee joint, located on the outer side. It connects the femur (thigh bone) to the fibula (the smaller bone of the lower leg) and provides stability by preventing excessive side-to-side movement.

Injuries to the LCL often occur due to direct impact or excessive stress on the inner knee, leading to pain, swelling, and instability.

Introduction

The lateral collateral ligament (LCL), sometimes called the fibular collateral ligament, is one of the primary ligaments stabilizing the knee joint. Its primary purpose is to keep the knee from turning too much in a varus or posterior direction.

Although it happens less frequently than other ligament injuries, the most common cause of injury to the knee’s LCL is a high-energy strike to the anteromedial knee that combines hyperextension and severe varus force.

The LCL can potentially be injured by non-contact varus stress or non-contact hyperextension. About 40% of all LCL instances occur in sports like football, hockey, basketball, skiing, or soccer that require high-velocity turning and jumping. Gymnastics and tennis are the sports with the highest risk of an isolated LCL tear.

Sprains (grade I), partial ruptures (grade II), and complete ruptures (grade III) are the three types of LCL injuries that can occur. When the lateral knee components are injured, the LCL is typically followed by further injury to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), and posterior lateral corner (PLC). This is because LCL injuries are rarely isolated.

The lateral collateral ligament, or LCL, is an important band of tissue on the outside of your knee. Athletes are more likely to tear it, which can cause excruciating pain and other symptoms. Depending on the severity, LCL tears usually heal in three to twelve weeks. However, you must take care of yourself. Use crutches, apply ice to your knee, and follow your doctor’s instructions.

Anatomy of Lateral Collateral Ligament

Origin: The LCL originates from the lateral epicondyle of the femur, a bony projection on the outside of the thigh bone (femur). This is the ligament’s proximal attachment site.

Insertion: The fibula, the smallest of the two lower leg bones, is where the LCL attaches distally. The ligament attaches itself to the fibula, directly beneath the knee joint.

The iliotibial band-aids in the insertion of this ligament, which is closely related to the joint capsule at the proximal level but does not come into direct touch with it because of a fat pad that separates them. The popliteus tendon is located deep in the LCL, separating it from the lateral meniscus. The LCL also separates the biceps femoris into two parts.

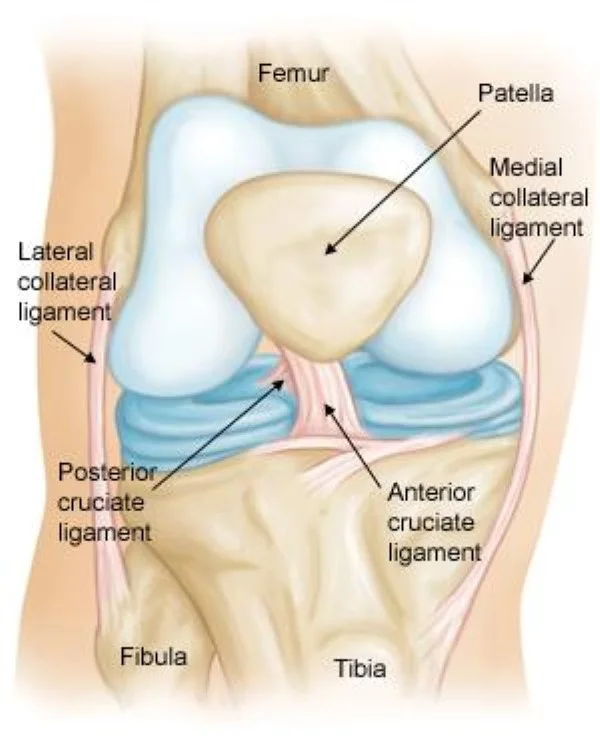

The knee joint is made up of the femur, or thighbone, patella, or kneecap, and tibia, or shinbone. The kneecap sits in front of the joint to provide some little protection.

A bone is joined to another bone by ligaments. Your knee is made up of four main ligaments. They serve as strong cables to hold the bones together, preserving the stability of your knee.

The ligaments on the sides. These are on each side of your knee. Your knee’s side-to-side motion is managed, and it is reinforced against aberrant movement.

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is an internal structure. It connects the femur and tibia.

The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is the outermost structure. It connects the femur to the smaller fibula, which is the bone in the lower leg.

Cruciate Ligaments.The anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments, which control how your knee travels forward and backward, cross over to form an X, with the anterior ligament in front and the posterior behind. Inside the knee joint are these.

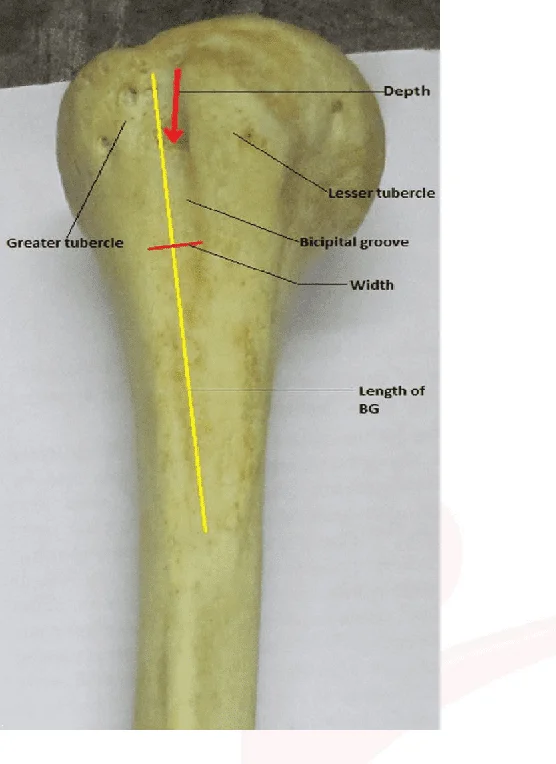

The LCL emerges from an osseous depression slightly posterosuperior to the lateral femoral epicondyle and attaches to the anterolateral fibular head 4,5. Usually about 50 mm in length, it looks more like a rope than a band.

Due to its lack of attachment to the lateral meniscus or knee capsule, it is more flexible and less prone to injury than the medial collateral ligament.

From its origin, the LCL runs downward and slightly backward to the head of the fibula bone, where it inserts. Located on the outside of the lower leg, the long, thin fibula bone contains muscle attachment sites. The head of the fibula is a rounded bony protuberance at the top of the bone that is a component of the knee joint.

The LCL inserts into the fibula bone in two separate places. On top of the bone, on the flat, outward-facing lateral surface of the fibular head, is the first point of insertion. The posterior portion of the fibular head, which faces backward, is where the second point of insertion is situated.

Finally, from its lateral epicondyle of the femur bone, the LCL inserts into two distinct places on the fibula bone’s head. Stabilizing the knee joint and preventing excessive rotation and side-to-side motions depend on the LCL attachment sites.

Function of Lateral Collateral Ligament

When the tibia rotates posterolaterally concerning the femur and experiences varus stress, the LCL stabilizes the lateral side of the knee joint. Anterior and posterior tibial translations are stabilized by the LCL if the cruciate ligaments are strained.

Varus rotation between 0 and 30 degrees of knee flexion is the primary constraint. The LCL’s function as a varus-stabilizing structure diminishes with knee flexion. Stretching the LCL happens when the knee is extended.

For the knee joint to remain stable and to prevent excessive lateral (outward) movement of the tibia (shin bone) about the femur (thigh bone), the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is necessary. This is a succinct overview of its primary goal:

- Defying Varus Forces: The main responsibility of the LCL is to resist varus forces. Varus forces are the forces that push the knee joint away from the midline of the body and outward. These pressures typically show up when cutting actions or sudden direction shifts are used in sports. Through its stabilizing function, the LCL protects the knee joint from these varus forces.

- Stabilizing the Lateral Aspect of the Knee: The biceps femoris tendon and the iliotibial band (IT band) are two additional structures that the LCL works with to assist in maintaining the overall stability of the lateral portion of the knee joint. This stability is necessary to maintain proper alignment and function during weight-bearing activities like running, jumping, and walking.

- Ligamentous Integrity Support: The LCL provides the knee joint with total stability and support in conjunction with the other knee ligaments, including the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), and medial collateral ligament (MCL). By transmitting stresses uniformly throughout the joint, these ligaments work together to reduce the risk of injury and promote healthy movement patterns.

- Contributing to Joint Kinematics: By preventing the tibia from moving too laterally, the LCL helps the knee joint move smoothly and with coordination. This function is necessary for activities involving pivoting, changing directions, and weight-bearing movements.

Maintaining the stability, integrity, and usefulness of the knee joint depends on the lateral collateral ligament, which is a crucial component. These functions may be hampered by LCL injuries, which can lead to symptoms like discomfort, instability, and reduced mobility. Therefore, knowing how the LCL works is essential for identifying, treating, and recuperating from knee joint diseases.

Relations

The popliteus tendon (via the popliteal hiatus), a bursa, and the lateral inferior geniculate arteries and nerve all reach profoundly to the LCL. The iliotibial band is connected to Gerdy’s tubercle and lies superficially to the LCL.

The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) of the knee joint has multiple important connections to adjacent knee and lower extremity tissues. A comprehensive assessment of knee injuries and their impact on joint stability and functionality requires an understanding of these connections. The main connections of the lateral collateral ligament are as follows:

- Tibia and Femur: The LCL connects the two bones by running from the head of the fibula, a bony projection on the outside of the knee joint, to the lateral epicondyle of the femur (thigh bone). It helps to stabilize the knee by restricting the tibia’s excessive lateral movement about the femur.

- Fibula: The LCL, which is connected to the fibula’s head, stabilizes the lateral aspect of the knee joint. The fibula distributes forces and preserves the overall structural integrity of the lateral knee components as the ligament’s secondary site of attachment.

- Popliteus Tendon: The LCL and the popliteus tendon are closely related. It enters the posterior side of the tibia after emerging from the lateral femoral condyle. When combined, these structures aid in stabilizing the lateral aspect of the knee and unlocking the knee during the early stages of knee flexion.

- Iliotibial Band (IT Band): On the lateral surface of the thigh, the iliotibial band is a thick band of fascia that joins the hip and tibia. Although the LCL and the IT band are not directly connected, they do have a functional relationship that can influence the biomechanics of the knee joint and support the lateral aspect of the knee.

- Tendon of the Biceps Femoris: This hamstring tendon attaches to the fibular head near the location where the LCL inserts. These structures work together to support and stabilize the lateral knee complex.

- Peroneal Nerve: As it travels down the lateral part of the knee, the peroneal nerve and the LCL are adjacent. Deficits in the sensory or motor function of the lower leg and foot can occasionally be caused by nerve injury or irritation from knee injuries, including those involving the LCL.

Knowledge of the relationships between the lateral collateral ligament and surrounding structures is essential for the accurate diagnosis and management of knee injury. When one of these components malfunctions or is injured, it might impact knee stability, function, and overall lower extremity biomechanics.

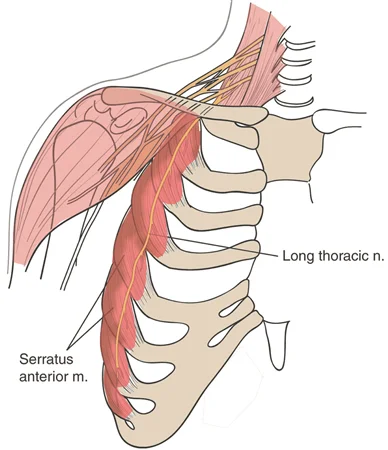

Innervation

- The biceps femoris is the name of the muscular branch of the tibial nerve.

- The common fibular nerve should be severed at the popliteal fossa.

- A branch of the common fibular nerve is located at the head of the fibula.

The innervation of the knee joint’s LCL involves neural systems that send sensory feedback from the ligament to the central nervous system. Despite the absence of sensory nerve fibers in its structure, the LCL is encircled by tissues that are innervated.

Both the transmission of sensory information regarding joint position and movement and the detection of mechanical stress are facilitated by these structures. The main components of the innervation of the LCL are as follows:

- Genicular Nerves: These nerves are made up of the sciatic, femoral, and obturator branches. Numerous components, including the ligaments, periosteum (the outer layer of bones), and joint capsule, receive sensory fibers from the intricate network of neurons that surround the knee joint. Despite the absence of direct innervation in the LCL, the genicular nerves innervate the surrounding tissues and provide sensory feedback about the mechanical stress involved in joint movement and loading.

- Peroneal Nerve: The peroneal nerve is a branch of the sciatic nerve that passes along the knee’s lateral side. It may also be involved in the sensory feedback from the lateral aspect of the knee joint, including structures near the LCL, even though its primary function is innervating the lower leg muscles and providing sensory innervation to the skin of the lateral leg and the dorsum of the foot.

- Proprioceptive Feedback: Proprioception is the body’s ability to sense its location, motion, and force imparted to its constituent parts. The joint capsule, which contains mechanoreceptors sensitive to changes in joint position and movement, is one of the surrounding tissues from which ligaments without specialized proprioceptive nerve endings, like the LCL, nevertheless receive proprioceptive information indirectly. This type of proprioceptive feedback aids in joint stability and coordination.

- Referred Pain: Referred pain is a condition where stress or injuries to the LCL and surrounding structures cause pain to be felt in places that are far from the actual site of injury. For example, pain referred from the LCL or lateral knee structures may be felt along the distribution of the peroneal nerve or at various locations within the knee joint.

Despite the limited innervation of the LCL itself, the surrounding neuronal structures play a critical role in giving sensory data relating to joint mechanics, location, and potential injury. To identify and treat conditions affecting the lateral aspect of the knee joint, it is essential to understand these neurological pathways.

Blood supply

Anterior tibial recurrent artery and lateral inferior genicular artery.

The genicular arterial network provides blood to the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) through some tiny arteries. The genicular arterial network, a complex network of small arteries, supplies blood to the knee joint and surrounding tissues.

The main arteries supplying blood to the left collateral ligament (LCL) are the lateral superior genicular artery and the lateral inferior genicular artery. These arteries split out from the popliteal artery, a major artery located behind the knee.

The lateral superior genicular artery, which runs along the outside of the knee joint, supplies blood to the top portion of the LCL. The lateral inferior genicular artery, which runs along the lower margin of the LCL, provides blood to the lower portion of the ligament.

In addition to these arteries, several smaller branches give blood to the LCL. These include the anterior tibial recurrent artery, which provides blood to the anterior portion of the LCL, and the fibular collateral artery, which feeds blood to the lateral side of the knee joint.

Finally, because the LCL is constantly supplied with oxygen and nutrients from several arteries, it has a very robust blood supply. This helps the LCL maintain its strength and health so it can perform its vital job of supporting the knee joint.

Injury to the lateral collateral ligament

The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is usually injured when the inside of the knee is struck directly, forcing the knee outward beyond its natural range of motion. Sports like basketball, football, soccer, and skiing can cause these injuries, especially when there is contact or abrupt direction changes. The severity of LCL injuries can vary from minor sprains to partial or total ligament rupture.

LCL tears: What are they?

An injury to the knee that results in pain, swelling, and bruises is called a lateral collateral ligament (LCL) rupture. Your LCL is the band of tissue on the outside of your knee that faces away from your body. This tissue connects the thigh bone to the bones of your lower limbs. It will stop the unnatural outward bending of your knee.

Athletes who play football soccer or ski are more likely to have an LCL rupture, which could prevent them from participating. However, with adequate time, care, and therapy, you should be able to return to sports.

The following are some typical reasons and signs of LCL injuries:

Causes:

- Direct trauma or impact to the outside of the knee, like from a sports collision or tackle.

- Knee joint hyperextension or sudden twisting, particularly while the foot is firmly planted on the ground.

- Knee joint overuse or repetitive strain, especially with activities involving a lot of cutting or pivoting.

Symptoms:

- Knee pain along the outside, particularly when bending or bearing weight.

- Soreness and swelling in the vicinity of the LCL.

- Knee instability or a giving-way sensation, especially when walking or doing physical exercise.

- Having trouble properly bending or straightening the knee.

- Discoloration or bruises surrounding the knee joint.

Treatment of lateral collateral ligament

For LCL injuries, first assistance needs to be given right away. This entails elevating the knee above the heart, applying ice to the wounded area, and taking pain medications. It is important to seek medical assistance immediately because the LCL is not often the only ligament injured. When other ligaments are injured, surgery is necessary to prevent additional knee instability.

However, if the ligament has been pulled directly off the bone, the treatment is the same as for an MCL sprain. If the LCL is the only lesion you have, surgery may be required. Your treatment plan will also include other aspects of your knee that your LCL strain may have impacted.

Conservative treatment

- Rest: The knee needs to rest in order to heal. Limit your weight-bearing activities and stay away from painful or uncomfortable activities.

- Ice: The healing process depends on your wound being kept frozen. Applying ice directly to the injured area for 15 to 20 minutes at a time, with at least an hour between treatments, is recommended. This is the proper way to handle an injury. When applied directly to the skin, blue ice and other chemical cold products do not work as well.

- Compression: To lessen swelling and provide support for the knee, wear a brace or compression bandage.

- Elevation: One possible way to lessen swelling is to raise the injured leg above the level of the heart.

- Bracing: You must protect your knee from the same sideways force that caused it to get hurt. You may need to modify your daily routine to avoid risky maneuvers. Your doctor may recommend wearing a brace to help prevent stress on the torn ligament. For more knee protection, your doctor may recommend crutches to keep you from putting weight on your leg.

- Physical therapy: Your doctor may suggest strengthening exercises. Specific exercises will help your knee regain function by strengthening the leg muscles that support it.

- Medication: Acetaminophen and ibuprofen are examples of over-the-counter pain medications that can reduce inflammation and pain.

- Injection therapy: Injections of corticosteroids can be used to lessen knee pain and inflammation.

It’s important to keep in mind that not all LCL injuries can benefit from conservative therapy, especially if they are severe or involve other knee issues. The LCL may need to be repaired or rebuilt surgically in certain situations. The optimal course of action for your specific injury will depend on your consultation with a medical specialist.

Physiotherapy Management

For an LCL injury, physiotherapy uses manual therapy and exercises to restore knee function, decrease pain and inflammation, and encourage recovery. The following are typical physiotherapy interventions for LCL injuries:

- Range of motion exercises: These exercises increase the knee’s range of motion and flexibility. Knee bends, heel slides and ankle pumps are a few examples.

- Strength training: These exercises build up the muscles that support the knee joint, such as the quadriceps, hamstrings, and calf. Exercises like squats, leg lifts, and calf raises are examples.

- Balance and proprioception exercises increase balance and coordination, lowering the likelihood of re-injury. Step-ups, wobble-board workouts, and single-leg stands are three examples.

- Manual treatment techniques: These methods are used to alleviate knee pain and inflammation. Some examples include stretching, massage, and joint mobilization.

- Modalities: Ultrasound, electrical stimulation, and ice/heat therapy can all assist in alleviating knee pain and inflammation.

- Functional training: Exercises that imitate daily or athletic movements to improve knee function.

Physiotherapy treatment approaches differ depending on the degree of the injury, age, activity level, and health state. Working closely with a physiotherapist is essential for developing a personalized treatment plan based on your specific needs and goals.

How may the risk of injury be decreased?

To reduce the risk of LCL injury, the knee joint must be protected and stabilized. The following methods can help reduce the likelihood of LCL injuries:

- Maintain a healthy weight: Carrying too much weight can put extra strain on the knee joint, increasing the risk of an LCL injury. Eating a balanced diet and exercising regularly can help you maintain a healthy weight and reduce your risk.

- Wear correct footwear: When participating in physical exercise, wearing shoes with adequate support and cushioning can assist in reducing the impact on the knee joint. This may reduce the danger of LCL injury.

- Practice good biomechanics: Maintaining adequate alignment and form during physical exercise will reduce knee joint stress and prevent LCL injuries. Working with a coach or trainer could help you learn the proper methods for your sport or hobby.

- Warm-up and cool down properly: By taking the time to warm up before exercise and cool down afterward, you may help prepare your muscles and joints for exercise and lower your risk of injury.

- Strengthen the muscles around the knee: To improve knee stability and reduce the chance of LCL injuries, strengthen the muscles that support the knee joint, such as the hamstrings and quadriceps.

- Wearing correct equipment, such as knee braces or padding, can reduce the incidence of LCL injuries and protect the knee joint during physical exercise.

- Rest and recover: After engaging in physical activity, taking some time to rest and recuperate can help prevent overuse injuries, which increase the risk of LCL problems.

Following these instructions can help people reduce their risk of LCL injuries while also ensuring the stability and health of their knee joints.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is a critical component of the knee joint that provides stability and support, particularly when the knee is driven outward by varus stresses. Clinicians must understand the LCL’s anatomy, function, and clinical consequences to adequately diagnose, treat, and rehabilitate knee injuries.

LCL injuries range in severity from small sprains to major rips, causing discomfort, swelling, instability, and difficulty bearing weight on the affected leg. A thorough physical examination is required for an accurate diagnosis, which is frequently aided by imaging studies such as MRIs.

Depending on the severity of the injury, there are several treatment options for LCL injuries, including bracing, physical therapy, and rest, as well as surgery in more serious cases. Rehabilitation, which focuses on strengthening muscles, increasing the range of motion, and progressively reintroducing functional activities, is critical for restoring function and stability to the knee joint.

Many persons with LCL injuries can return to their pre-injury level of activity and achieve good outcomes with the correct diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation. The severity of the injury, the presence of concurrent knee problems, and the patient’s adherence to rehabilitation standards are all factors that influence the prognosis.

In clinical practice, enhancing results and permitting a safe return to activity following LCL injuries requires a comprehensive plan that takes into account the particular needs of each patient. Future research and developments in diagnosis, treatment techniques, and rehabilitation approaches will increase our understanding and management of LCL injuries even more.

FAQs

Where did the lateral collateral ligament form?

The primary purpose of the lateral collateral ligament, which originates on the lateral epicondyle of the femur and inserts on the fibular head, is to prevent excessive varus stress and posterior-lateral knee rotation.

What is the structure of the MCL and LCL?

The fan-shaped medial (ulnar) collateral ligament (MCL) supports the glenohumeral and radiohumeral joints. The lateral (radial) collateral ligament (LCL) provides lateral support for the glenohumeral and radiohumeral joints. Its structure resembles a rope.

What is the LCL’s length?

The LCL attaches to the anterolateral fibular head after starting in an osseous depression slightly posterosuperior to the lateral femoral epicondyle. Its normal length is about 50 mm, and it looks more like a rope than a band.

What exactly is the ligament that lies behind the LCL?

On the inside lies the medial collateral ligament (MCL). It connects the tibia and femur. The outside houses the lateral collateral ligament (LCL). It connects the smaller lower leg bone, fibula, to the femur.

What is the anatomical name of the lateral collateral ligament?

The fibular or lateral collateral ligament (LCL), which serves as the primary knee varus stabilizer, is a cord-like band. It is one of four important ligaments that help to stabilize the knee joint.

What is the function of the LCL?

The LCL starts between the top of the fibula, the bone on the outside of the lower leg, and the outer portion of the lower thigh bone, which is positioned on the outside of your knee. The ligament helps to stabilize the exterior section of your knee joint.

Where exactly is the LCL located?

A short band of connective tissue known as the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) runs around the outside of the knee. It connects the fibula, the slenderer long bone of the calf, to the femur, or thighbone.

Is the MCL larger than the LCL?

The MCL had larger attachments than the LCL, except for the proximal attachment’s longitudinal diameter. When the knee was fully extended, the MCL had a backward inclination while the LCL had a forward one.

What is the LCL—a tendon or a ligament?

The LCL is a thin band of tissue that extends the length of the outside of the knee. Thousands of people experience LCL strains, partial tears, or tears every year.

How does LCL relate to this?

The LCL is one of the knee’s four major ligaments. The LCL helps connect the thigh bone, the femur, to the bigger shin bone, the fibula, on the outside of the knee. The LCL prevents the knee from buckling outward.

How can LCL be avoided?

Using a knee brace.

Some athletes, like football linemen or snow skiers, attempt to reduce their chance of an LCL tear by wearing specific knee braces made to restrict side-to-side movement.

Which two bones is the LCL attached to?

The lateral collateral ligament is a small band of tissue that runs along the outside of the knee. It connects the thighbone (femur) to the fibula, the tiny bone of the lower leg that goes down the side of the knee and connects to the ankle.

How does the LCL keep the knee stable?

The ligament that joins the femur and fibula is known as the lateral collateral ligament, or LCL. The LCL helps to stabilize your knee. Like the medial collateral ligament, this ligament helps to limit excessive side-to-side movement of the knee joint. It keeps the lower and upper legs in proper alignment.

Can someone with an LCL tear walk?

Wearing a hinged knee brace may also be necessary once your doctor has cleared you to bear weight on your leg. The majority of people return to their prior level of exercise within three to four weeks. grade two or above for injuries. This may require the use of crutches and hinged knee braces.

Is LCL able to heal itself?

The ligament will repair itself, thus, it’s crucial to prevent injuries during the healing process. During the healing phase, it is advised to perform range-of-motion exercises and gradually strengthen the quadriceps (thigh muscles) and biceps femoris (hamstring muscles).

What is the recovery period following LCL surgery?

LCL Surgery Recuperation

Although some may need to stay overnight, patients can typically leave the hospital a few hours after surgery. Rehabilitating after hospital discharge usually involves using crutches for no more than six weeks.

What is the LCL orthopedic test?

The most useful special test for assessing an LCL injury is the Varus Stress Test. With the femur stabilized, a varius force is administered, with special attention to the lateral joint line. The test is first conducted with the body in a 30-degree flexion position. Increased laxity or gapping is a sign of an LCL injury with possible PLC involvement.

What is the duration of the healing process for LCL?

Grade I: It usually takes three weeks for a grade I LCL tear to heal. Grade II: Three to six weeks may be needed for the healing of a grade II partial LCL tear. Grade III: It takes more than six weeks for the LCL to heal completely following a tear.

Are injuries to the LCL considered serious?

In contrast to tears in the medial collateral ligament, lateral collateral ligament tears take longer to heal. Grade 3 rips of the lateral collateral ligament may require surgery. Sometimes braces, ibuprofen, physical therapy, rest, and pain medication are all that is required.

References

- Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury of the Knee. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Lateral_Collateral_Ligament_Injury_of_the_Knee.

- Image –Redirect Notice. (n.d.). https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fadamcohenmd.com%2Flateral-collateral-ligament&psig=AOvVaw3pYPt-B-wc-8sb_Ps6dF7o&ust=1708088718188000&source=images&cd=vfe&opi=89978449&ved=0CBMQjRxqFwoTCKj4soW_rYQDFQAAAAAdAAAAABAE.

- Collateral Ligament Injuries – OrthoInfo – AAOS. (n.d.). https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases–conditions/collateral-ligament-injuries/.

- Lateral Collateral Ligament of the Knee. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Lateral_Collateral_Ligament_of_the_Knee.

- Knipe, H., & Su, S. (2014, October 3). Lateral collateral ligament of the knee. Radiopaedia.org. https://doi.org/10.53347/rid-31367.

- Gameti, D. (2024, March 20). Lateral collateral ligament – anatomy, structure, function. Mobile Physiotherapy Clinic. https://mobilephysiotherapyclinic.in/lateral-collateral-ligament-lcl/

One Comment