Medial Antebrachial Cutaneous Nerve

Introduction

The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve is a sensory nerve originating from the medial cord of the brachial plexus, primarily carrying fibers from the C8 and T1 nerve roots. It supplies sensation to the skin of the medial (inner) side of the forearm.

The nerve descends along the arm, often near the basilic vein, and divides into anterior and posterior branches to innervate the skin. It’s important in clinical assessments for nerve injuries and can be affected in conditions like cubital tunnel syndrome.

In addition to the antebrachial cutaneous nerve, which also gives off a small cutaneous branch in the arm that supplies the skin overlying the biceps brachii muscle, the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm has two terminal branches: the anterior branch, which is the larger branch that descends in the anteromedial aspect of the forearm, coursing anterior to the median cubital vein, and the posterior branch, which is usually located in the proximo-medial region of the behind arm.

Structure

The skin of the upper arm, shoulder, and back is sensory innervated by the paravertebral skin, which is located around three inches on either side of the dorsum of the back. The dorsal principal ramus of the mixed spinal nerves innervates this region. From a dorsal root ganglion, the ventral ramus of the mixed spinal nerve supplies the remaining somatic region innervated by a single spinal neuron.

The Dermatome’s Function in the Upper Limb’s Sensory Innervation

While the C6 dermatome extends over the lateral portion of the forearm, covering the ventral aspect of the medial thumb and the lateral aspect of the index finger, the C5 dermatome is located over the skin of the shoulder and runs along the lateral aspect of the arm. The middle finger occupies the C7 dermatome, which begins more medially than the C6 dermatome in a laminar way.

A dermatome, which comes from the Greek word meaning skin cuts, is innervated by each dorsal root ganglion. Compared to the C7 dermatome, the C8 dermatome crosses the more medial lamina. From the elbow down the ventral arm and forearm, the C8 dermatome innervates the ventral side of the ring and little fingers. The T1 dermatome supplies the arm’s medial aspect. The dermatomes are situated posteriorly, much like the ventral side of the forearm.

The dermatomes that supply the arm and forearm also innervate the hand and cross the wrist, which is a significant feature. In contrast, the medial, lateral, and posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerves—the peripheral nerve regions that supply the forearm—do not pass through the wrist. When it comes to the clinical diagnosis and localisation of peripheral neuropathies, this differentiation is crucial.

Neurological lesions that affect a nerve root are categorized as radiculopathy (from the Latin radix = root). The brachial plexus is affected by another set of lesions (see below). We call them plexopathies. A loss of feeling associated with one or more dermatomes will be present in both of these clinical categories.

On the other hand, peripheral nerve lesions, also known as neuropathies, affect peripheral nerves. These do not exhibit the dermatomal pattern of anaesthesia, or lack of feeling. Instead, each peripheral nerve has its unique pattern. For instance, an ulnar nerve lesion causes anesthesia across the whole little finger and the medial aspect of the ring finger. The area proximal to this lesion is supplied by the forearm’s medial cutaneous nerve rather than the ulnar nerve.

Loss of feeling across the ring and little fingers would result from a lesion that seems to be comparable in the anesthesia region. The medial forearm is similarly affected by this disease. An illustration of a C8 dermatome is this one. This lesion may be a C8 radiculopathy or a component of a C8-related lesion in the lower brachial plexus.

Loss of motor function, which may be a component of these disorders, is another difference. Myotomes are those that, like dermatomes, innervate the muscular in a segmental manner. One significant difference is that the myotomes are orientated proximally to distally, whereas the dermatomes on the upper limb are orientated superior to inferior. Therefore, the shoulder muscles are innervated by the upper portion of the brachial plexus (such as the C5 and C6).

An essential idea is that loss of sensation can result from damage to the fine touch fibers caused by neurological disorders like neuropathy, plexopathy, or radiculopathy. The pain fibers, however, might continue to fire or even become hyperactive (hyperalgesia, which is Greek for “excess plus pain”). Compared to the much bigger fine-touch fibers, the pain axons are considerably tiny and have far lower metabolic needs, which allows them to survive. Paraesthesia is the word used to describe the lack of delicate touch feeling amid normal or hyperactive pain perception. The patient is frequently more disturbed by hyperalgesia (increased pain perception) than by the loss of delicate touch perception.

The Brachial Plexus

The ventral rami of the C5-T1 spinal segments form the brachial plexus, which provides the peripheral nerves that innervate the upper limb. Each spinal segment is made up of a motor ventral root, which contains motor neurons in the spinal cord’s ventral horn, and a dorsal root, which has sensory function with each level’s cells in the dorsal root ganglion. The dorsal primary ramus, which innervates the paravertebral muscles and skin, and the ventral primary root, which innervates the anterolateral muscles and skin, split off from the dorsal and ventral roots to produce a mixed spinal nerve.

There is some misunderstanding regarding the fact that the spinal cord has roots that extend from it. The roots of the brachial plexus, which are not the roots of the spinal cord, are formed by the ventral main ramus at each level.

There are divisions, cables, branches, roots, and trunks in the brachial plexus. The C5 ventral ramus gives rise to the C5 nerve root. The C6 ventral ramus forms the C6 root of the brachial plexus, and so on. The superior (upper) trunk of the brachial plexus is formed by the union of the C5 and C6 roots. As the middle trunk, C7 continues. The inferior (lower) trunk of the brachial plexus is made up of C8 and T1.

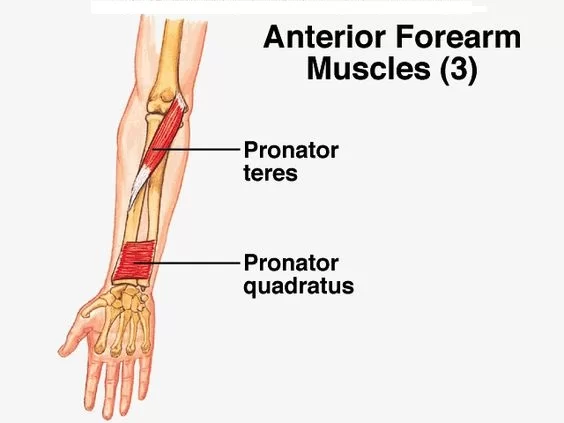

After that, each trunk splits into anterior and posterior halves. The muscles of the anterior portion of the upper limb are innervated by the anterior divisions. The biceps brachii, brachialis, flexor digitorum superficialis, and flexor digitorum profundus are examples of flexor muscles. The upper limb’s posterior musculature is innervated by the posterior divisions. These muscles are often upper limb extensors, including the brachioradialis, triceps brachii, and muscles with the term “extensor” in their nomenclature.

The anterior divisions give rise to two cords: the medial chord (C8, T1) and the lateral cord (C5, C6, C7). In general, the lateral cord’s muscles are located closer to the body than the medial cord’s. The posterior chord (C5, C6, C7, C8, T1) is one cord that originates from the posterior divisions.

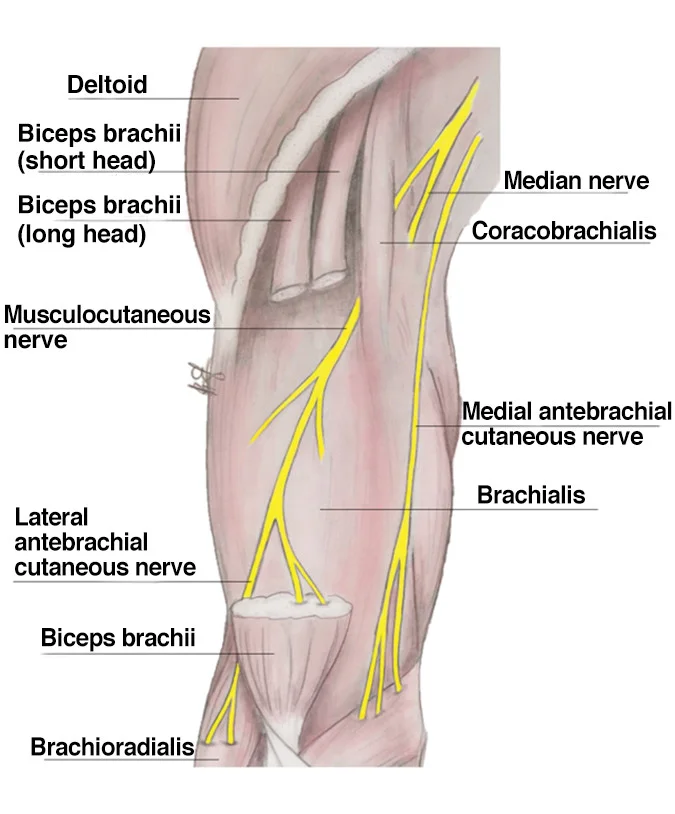

Regarding the arm’s cutaneous innervation (brachium), the arm is innervated by four cutaneous nerves. The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, also known as the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm, emerges only distal to the medial brachial cutaneous nerve, which is the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm and is produced by the medial cord. The superior (upper) lateral brachial cutaneous nerve is derived from the posterior cord through the axillary nerve. The inferior (lower) lateral brachial cutaneous nerve is similarly derived from the posterior cord through the radial nerve. Through the radial nerve, the posterior cord also gives birth to the posterior brachial cutaneous nerve.

Three nerves are involved in the antebrachium, or cutaneous innervation, of the forearm. The medial forearm is innervated by the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, which does not pass through the wrist. The musculocutaneous nerve, which innervates the BBC muscles (biceps brachii, brachialis, and coracobrachialis), originates from the lateral cord of the brachial plexus. The lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve is subsequently formed by the musculocutaneous nerve. Since none of the forearm’s sensory nerves pass through the wrist, the lateral forearm nerve’s domain terminates there.

The anterior portion of the inferior trunk of the brachial plexus continues into the medial cord, which has three non-terminal branches, including the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. The medial pectoral nerve, which supplies motor innervation to the pectoralis major and minor, and the medial brachial cutaneous nerve, which supplies sensory innervation for the medial arm, are the medial cord’s other two non-terminal branches. Additionally, the median nerve receives fibers from the medial cord, which eventually extends distally to the ulnar nerve.

The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve is located in the axillary fossa, next to the median and ulnar nerves, superficial to the axillary artery and vein. This nerve follows the basilic vein as it passes between the brachialis and triceps brachii muscles on its distal journey. The nerve then travels to the ulnar side of the brachial artery after entering the brachial fascia that covers the biceps brachii. Subsequently, the nerve travels alongside the basilic vein at elbow level before splitting distally into the volar and ulnar branches, which supply sensory innervation to the olecranon’s skin and medial forearm.

Regarding the hand, the posterior part of the thumb and the dorsum of the thenar web are innervated by the sensory cutaneous branch of the radial nerve. The medial thumb, lateral side of the index finger, medial side of the index finger, lateral side of the middle finger, medial side of the middle finger, and lateral side of the ring finger are all innervated by the median nerve. The hypothenar eminence, both sides of the little finger, and the medial side of the ring finger are innervated by the ulnar nerve.

Function

At each level, the (sensory) dorsal and (motor) ventral roots combine to form a mixed spinal nerve, which has a dorsal primary ramus and a ventral primary ramus (Latin for “branch”). The sensory functions of the upper limb skin are derived from neuronal cell bodies found in the dorsal root ganglia from C5 to T1.

Course

A sensory branch of the brachial plexus’s medial cord is the forearm’s medial cutaneous nerve. This originates from the anterior rami of spinal neurons C8-T1.

Alongside the ulnar nerve, the nerve descends the medial aspect of the upper arm after emerging from the branchial plexus. The basilic vein then penetrates the deep fascia to reach the subcutaneous plane.

After that, it divides into anterior and posterior branches.

Anterior branch: crosses the basilic vein anteriorly. Along the way, it supplies cutaneous branches to the skin as it descends the anteromedial side of the forearm.

Posterior branch: provides cutaneous branches to the skin as it travels over the posteromedial side of the forearm, following the medial border of the basilic vein.

Branches

Volar branch

The vena mediana cubiti (middle basilic vein) is often passed in front of, but sometimes behind, the bigger volar branch (ramus volaris; anterior branch).

Ulnar branch

The ulnar branch (ramus ulnaris; posterior branch) goes obliquely downhill on the medial side of the basilic vein, in front of the medial epicondyle of the humerus, to the back of the forearm to deliver filaments to the skin. It then falls to the wrist on its ulnar side.

The dorsal branch of the ulnar, the dorsal antebrachial cutaneous branch of the radial, and the medial brachial cutaneous are all in communication with it.

After there, it descends on the front of the forearm’s ulnar side, connecting with the palmar cutaneous branch of the ulnar nerve and sending filaments to the skin up to the wrist.

Embryology

The mesoderm-derived limb buds emerge from the developing embryo during the fifth week of development. The ectoderm is the origin of the brachial plexus. Thus, as the spinal cord’s segmental nerves pierce these limb buds, the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve develops.

The first thoracic segment and the fifth through eighth cervical segments are the origins of the brachial plexus. The brachial plexus splits into two branches: a ventral branch that innervates the flexor muscles and a dorsal branch that innervates the extensor muscles. Growth factors that help with limb placement at birth include fibroblast growth factor (FGF), sonic hedgehog (SHH), and homeobox (Hox) genes. Fibroblast growth factors aid in anterior-posterior limb patterning, homeobox genes aid in proximodistal limb patterning, and Sonic hedgehog signaling molecules control limb development.

Anatomical Variation

The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve’s branching pattern and structure have been shown to vary in several ways. In certain instances, the nerve itself emerges from the brachial plexus’ inferior trunk rather than the medial cord. Because of the anastomosis that has been reported between the posterior branch and the ulnar nerve, its palmar cutaneous branch, the medial brachial cutaneous nerve, and the posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerve, the posterior branch is quite varied.

In a different variant, the four medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve branches that have been identified appear before the anterior and posterior branches split off. The medial brachial cutaneous nerve typically innervates the medial, distal portion of the upper arm, where these branches migrate.

Clinical Importance

Clinical understanding of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve’s anatomy is essential since the nerve can be injured during a variety of operations, including cubital tunnel releases, therapeutic injections for elbow discomfort, and venipunctures. After such surgeries, it has been discovered that unintentional nerve injury can cause numbness, severe paresthesias, and dysesthesias.

A condition known as “snapping elbow” occurs when the elbow flexes and extends, producing a painful cracking sound that occasionally may even be seen, seen, and felt. The most common cause of this illness is a dislocation of the ulnar nerve over the medial epicondyle. A snapping of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve was discovered in individuals who reported a similar painful popping feeling in their elbow.

Athletes who throw repeatedly run the risk of injuring the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve as well as several other upper extremity nerves. Through compression and traction, throwing actions harm these nerves, resulting in a variety of neuropathic disorders. Lacerations, tuberculoid leprosy-induced neuritis, and subcutaneous lipomas are uncommon origins of injury to the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve.

Other origin of Damage to the Medial Cutaneous Nerve of the Forearm

Additional causes of injury to the forearm’s medial cutaneous nerve include elbow arthroscopy, open fracture fixation, steroids-injected medial epicondylitis, tumor incision, arthrolysis, tennis-related trauma, and compression neuropathy caused by a lipoma. Additionally, neuropathy of the forearm’s medial cutaneous nerve can be caused by continuous, intense shaking activities, such as shaking a rug. Raynaud syndrome may potentially include vascular branches.

Nerve blocks and percutaneous biopsy of the forearm’s medial cutaneous nerve

It has been demonstrated that percutaneous biopsy of the forearm’s medial cutaneous nerve aids in the identification of clinical diseases affecting this nerve. Surgery for arteriovenous fistulas in individuals with end-stage renal illness has demonstrated the effectiveness of medial and lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve blocks. It has been demonstrated that ultrasound-guided nerve blocks, which include the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm, are successful in surgical upper limb anesthesia.

Surgical Importance

When using forearm flaps as donor tissue in transplant surgery, it is crucial to comprehend the anatomy of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. Such flaps have been performed on the hands, mouth, and penis. Therefore, understanding the donor tissue’s cutaneous innervation is essential for optimal sensory recovery in these regions. Forearm free-flap phalloplasty is one such instance. This surgical method is utilized to construct a neophallus in transsexual procedures. The skin of the anterior forearm and a large portion of the surrounding tissue, including the medial and lateral cutaneous nerves of the forearm, are included in the flap used in this treatment. The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve itself is commonly utilized in brachial plexus reconstructions and can also be utilized in surgical transplants.

The ulnar nerve is crossed by posterior branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, which are typically located 2 cm distal to the medial epicondyle. Therefore, when ulnar nerve releases are performed at the elbow to treat cubital tunnel syndrome, they run the danger of getting hurt. Damage to the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve during such treatments can result in painful neuromas, hyperaesthesia, and hyperalgesia. As the “cable graft” for repairing peripheral nerves like the digital nerve, the anterior branch of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve is also crucial in surgery.

Understanding the structure of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve is important for several upper arm vascular procedures. These procedures include brachial artery and vein embolectomies, arteriovenous fistula steal syndrome surgery, thrombectomies, and arteriovenous fistula development between the brachial artery and basilic vein.

FAQs

What are the symptoms of antebrachial cutaneous nerve injury?

Symptoms include pain in the anterolateral elbow and searing dysesthesias extending into the lateral forearm, particularly when the forearm is completely pronated with the elbow extended.

How do you treat lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve?

Initially, patients receive conservative treatment that includes rest, activity modification, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and extension block splinting.

How might the arm’s medial cutaneous nerve be blocked?

By injecting a local anesthetic into the subcutaneous layers above the muscle fascia, cutaneous nerve blockage is accomplished. There are varying amounts of fat, superficial nerves, and arteries in the subcutaneous tissue.

How do you treat a cutaneous nerve injury?

In most cases, a cutaneous nerve injury sustained during surgery would heal gradually over time, reaching full recovery in six to nine months. Conservative measures such as medication, rest, orthotics, and physical therapy are commonly used to treat post-surgical cutaneous nerve damage.

Is nerve damage in the arm serious?

The brain’s capacity to interact with muscles and organs may be compromised by nerve damage. When peripheral nerve damage occurs, it’s critical to seek medical attention right once.Complications and irreversible harm may be avoided with early identification and treatment.

References

Antebrachial cutaneous nerves. (2023, November 3). Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/antebrachial-cutaneous-nerves

Wikipedia contributors. (2024e, September 1). Medial cutaneous nerve of forearm. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medial_cutaneous_nerve_of_forearm

Medial cutaneous nerve of forearm.(2023, July 30).https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551638/