Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury

Introduction

A Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) injury involves a sprain or tear of the ligament on the outer side of the knee, connecting the femur to the fibula. It often results from a direct blow to the inner knee or excessive stress during activities involving sudden changes in direction. Symptoms include pain, swelling, and instability in the knee. Treatment typically involves rest, physical therapy, and, in severe cases, surgical intervention.

One of the main ligaments that stabilizes the knee joint is the lateral collateral ligament (LCL), also known as the fibular collateral ligament. Its main function is to stop excessive varus and posterior-lateral rotation of the knee. Despite being less prevalent than other ligament injuries, a high-energy impact to the anteromedial knee that combines significant varus force and hyperextension is the most common cause of an injury to the knee’s lateral collateral ligament (LCL).

Non-contact hyperextension or non-contact varus stress can potentially cause injury to the LCL. Sports involving high velocity pivoting and jumping, such as football, hockey, basketball, and soccer, account for 40% of all LCL injuries. It has been demonstrated that the sports with the highest risk of an isolated LCL injury are tennis and gymnastics.

There are three types of LCL injuries: sprain (grade I), partial rupture (grade II), and total rupture (grade III). Since the LCL is rarely injured on its own, injuries to the lateral knee components frequently result in subsequent damage to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), and posterior-lateral corner (PLC).

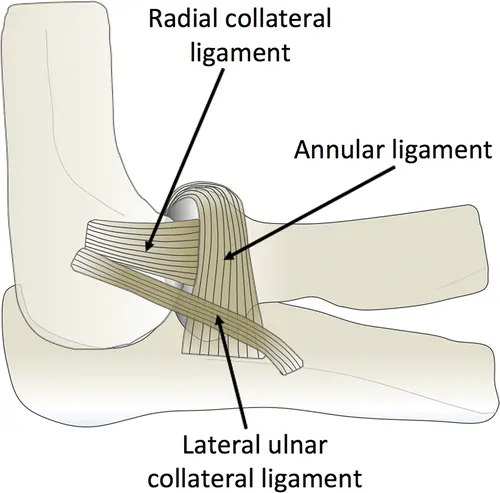

Clinically Relevant Anatomy:

Along with the biceps femoris tendon, popliteus muscle and tendon, popliteal meniscal and popliteal fibular ligaments, oblique popliteal, arcuate, and fabellofibular ligaments, and lateral gastrocnemius muscle, the LCL is a cord-like structure that is part of the arcuate ligament complex.

Strongly connecting the lateral epicondyle of the femur to the head of the fibula, the LCL serves as a knee stabilizer by preventing tibial external rotation and varus load on the knee. The LCL is loose when the knee flexes more than 30 degrees. When the knee is extended, the ligament is strained.

Epidemiology:

A collateral ligament damage affects 25% of individuals in the US who arrive at the emergency room with severe knee pain. It has been demonstrated that the largest occurrence occurs in adults between the ages of 20 and 34 and 55 and 65. MCL injuries are more frequent than LCL injuries among the collateral ligament injuries. Limited research has indicated that high-contact sports and women are more likely to sustain isolated LCL injuries.

Less than 2% of knee injury instances involve an isolated injury to the LCL because of its intimate relationship to the PLC, rear (PCL), and anterior (ACL) cruciate ligaments. However, between 7% and 16% of all knee ligamentous injuries involve injury to this ligament in addition to other tissues. With an incidence of 7.9%, isolated LCL injuries are the second least prevalent knee injury among high school athletes, according to studies. At 2.4%, PCL injuries are the least frequent. Forty percent of PLC and LCL injuries occur in contact sports. Non-sport-related trauma, such as falls and auto accidents, can also result in LCL damage.

Despite the paucity of research on isolated LCL injuries, data indicate that high-contact sports, female gender, and athletic activities involving high-velocity pivoting and jumping enhance the risk of injury. Overall, knee injuries are most common in soccer, whereas isolated LCL injuries are more common in tennis and gymnastics. According to a US military study, troops who have previously suffered a knee, ankle, or hip injury are more likely to sustain a lateral knee injury.

Cause of Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury:

Numerous actions that place stress on the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) might cause injury. The following are a few typical reasons for LCL injuries:

- Direct impact to the knee: The LCL may stretch or rupture if the knee is directly struck, as would happen in a vehicle accident or contact sport.

- Twisting or pivoting motions: The LCL may also be strained and torn by abrupt twisting or pivoting motions of the knee, which are frequently observed in sports like basketball or soccer.

- Knee hyperextension: The LCL may be overstressed and torn if the knee is compelled to bend backward beyond its natural range of motion.

- Sudden direction changes: The LCL may also strain or rupture if there are abrupt direction changes while running or jumping.

- Overuse injuries: Overuse injuries like tendinitis or inflammation of the ligament can result from repetitive stress on the LCL, such as jogging or leaping.

- Degenerative diseases: As we age, degenerative conditions like arthritis can weaken the LCL and make it more vulnerable to damage.

It is crucial to remember that LCL injuries frequently coexist with other knee problems, like meniscus or ACL tears. It’s critical to get medical help and obtain a precise diagnosis and treatment plan if you think you may have hurt your LCL.

Symptoms of the Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury:

The severity of the damage can affect the symptoms of an LCL injury. Typical signs and symptoms include:

- The most typical sign of an LCL injury is pain. The outside of the knee may be the site of mild to severe pain.

- Swelling: Another typical sign of an LCL injury is swelling around the knee. The outside of the knee may be the only area affected.

- Stiffness: Following an LCL injury, the knee may become stiff. It could seem tight and challenging to move the knee.

- Instability: The knee may feel shaky or unstable if the LCL is totally ruptured. Walking and bearing weight on the damaged limb may become more challenging as a result.

- Bruising: Following an LCL damage, there may be bruises surrounding the knee. The intensity of the injury will determine how bad the bruises are.

- Limited range of motion: An LCL injury may result in a knee with a restricted range of motion. Fully bending or straightening the knee may become challenging as a result.

- Clicking or popping sounds: When the knee is moved, an LCL injury may occasionally result in clicking or popping sounds.

Clinical Presentation:

Acute:

Acute LCL injury patients will typically have a history of an acute event, most often a blow to the medial knee during full extension or excessive noncontact varus bending. Along with trouble bearing full weight, the lateral joint line frequently exhibits pain, edema, and ecchymosis. A thrust gait, foot kicking at mid-stance, paresthesia down the lateral lower extremity, weakness, and/or foot drop are less frequent complaints.

When evaluated, a patient with an acute LCL injury may have decreased range of motion, quadriceps weakness (inability to perform a straight leg raise), and instability or giving way when bearing weight. During a Varus Stress Test, the patient will exhibit both pain and enhanced carbohydrate movement.

Sub-Acute:

Lateral knee soreness, stiffness with end-of-range flexion or extension, general weakness, and potential instability or giving way are all symptoms of a sub-acute LCL injury.

Chronic:

Unspecific knee pain, severe weakening along the whole kinetic chain, possible instability, and maladaptive movement patterns are all symptoms of a persistent LCL injury.

Risk factors of Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury:

On the outside of the knee is a ligament known as the lateral collateral ligament, or LCL. It stabilizes the knee joint and aids in limiting the knee’s excessive outward motion. The LCL can sustain damage from a number of causes, much like any other ligament. The following risk factors can raise the possibility of an LCL injury:

- Sports: Players who play sports like football, basketball, and soccer that require quick direction changes or contact with other players are more likely to get an LCL injury.

- Overuse: The LCL may sustain overuse injuries as a result of repetitive strain on the knee joint, such as long-distance jogging or jumping activities.

- Previously, knee injuries: LCL injuries are more common in people who have previously suffered knee injuries, such as meniscus or ACL tears.

- Poor biomechanics: Unusual knee joint alignments, including bowlegs or knock-knees, might increase the risk of injury and place additional strain on the LCL.

- Obesity: Carrying too much weight increases the risk of an LCL injury and puts extra strain on the knee joint.

- Age: Our ligaments lose some of their elasticity and become more vulnerable to damage as we age. LCL injuries may be more common in older people.

- Genetics: Some people are more likely to sustain an LCL injury if they are born with weaker ligaments.

How may the risk of injury be reduced?

Protecting and maintaining the stability of the knee joint is essential to lowering the risk of LCL injuries. The following strategies can help lower the chance of LCL injuries:

- Keep your weight within a healthy range because carrying too much weight might strain your knees and raise your risk of an LCL injury. This risk can be decreased by maintaining a healthy weight through regular exercise and a well-balanced diet.

- Wear the right shoes: When engaging in physical activity, wearing shoes that provide optimal support and cushioning will help lessen the impact on the knee joint. By doing this, LCL injuries may be avoided.

- Use proper biomechanics: LCL injuries can be avoided, and knee joint tension can be lessened with proper alignment and form during exercise. To master the right techniques for your sport or activity, you might need to work with a coach or trainer.

- Properly warming up and cooling down before and after physical activity can help prepare the muscles and joints for exercise and help avoid injury.

- Strengthen the muscles surrounding the knee: By strengthening the quadriceps and hamstrings, which support the knee joint, you can increase knee stability and lower your risk of LCL injuries.

- Wear the right gear: Wearing the right gear, like braces or knee pads, can help protect the knee joint when exercising and lower the chance of LCL injuries.

- Rest and recovery: After engaging in physical activity, it’s important to take some time to rest and recover to avoid overuse injuries, which raise the risk of LCL problems.

Differential Diagnosis:

Because of its proximity to surrounding tissues, LCL injuries are commonly observed in conjunction with knee dislocations and other ligamentous injuries such as ACL, PCL, and PLC. An LCL injury can also result in meniscal tears or injuries, however, these are less frequent. It’s important to rule out other conditions, such as distal hamstring tendinopathy, iliotibial band syndrome, and popliteus avulsion.

Because ACL and PCL tears share generic characteristics like swelling, acute-onset pain, and knee instability, they are frequently mistaken for LCL injuries. It should be easier to distinguish between the injuries using the anterior or posterior drawer tests.

Because of their common generic characteristics, including swelling, buckling, and lateral joint line pain, lateral meniscus tears are frequently confused with LCL tears. A lateral meniscus tear can be distinguished by a positive McMurray test, which is not observed in LCL tears.

Posterolateral knee soreness distal to the lateral femoral epicondyle is a common presentation of popliteal injury, specifically tendinopathy, which is worse by walking downhill. The cause of popliteal pain can be identified with the use of a positive Gaiter test. As the patient resists, the knee is flexed and the tibia is externally rotated to conduct this test. This maneuver eliminates pain in LCL injuries.

LCL tears may be a sign of a bone contusion. One way to find the contusion is to stress the knee and palpate the lateral joint line. Lateral bone contusion pain will not be impacted by varus stress.

Pain at the lateral distal femoral epicondyle that develops over time is a symptom of ITB syndrome. It shouldn’t be possible to reproduce pain through varus stress.

Diagnosis of Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury:

Physical Examination:

Crucial information required for a diagnosis will be obtained from data collected during a subjective evaluation. The doctor can determine the best differential diagnosis by doing a thorough physical examination. Patients with a suspected LCL injury will have ecchymosis, edema, and maybe elevated warmth along the lateral joint line when they are observed. Along with a thorough evaluation of range of motion, palpation along the lateral joint line should be carefully considered. In order to detect the typical ‘varus thrust’ finding that is frequently seen in LCL injuries, a gait analysis should be conducted whenever possible. Since isolated LCL injuries are rare, specific testing should be carried out to identify any related soft tissue, meniscal, or ligamentous injuries.

Patients frequently come in with a history of severe noncontact varus bending or an acute medial blow to the fully extended knee. Following an accident, sudden lateral knee pain, edema, and ecchymosis are common. The ipsilateral foot kicking in midstance or a thrust gait may also be described by the patient. Patients may report weakness or a foot drop, as well as lateral lower extremity paresthesias.

It is necessary to get a thorough personal medical history, covering clotting diseases, prior operations, occupation, gait, use of ambulation-assisted devices, and living arrangements, such as ascending stairs at home.

For every patient, a thorough complete range-of-motion knee examination is essential. Lateral knee soreness on palpation is the most often observed exam finding. Additionally, pain may be felt along the patellar tendon attachment, Gerdy’s tubercle, and the infrapatellar bursa. There may be ecchymosis, swelling, and warmth. It is important to look at gait for the traditional “varus thrust” finding.

Objective Assessment:

- Observation

- Palpation

- Active range of movement (ROM)

- Muscle testing

- Gait analysis

- Special tests

- Neurological Exam (if required).

Special Tests:

Varus Stress Test:

When evaluating an LCL damage, this is the most helpful particular test. A varus force is administered, paying particular attention to the lateral joint line, once the femur has stabilized. First, the test is conducted in a 30-degree flexion position. The test is then conducted with the knee fully extended. While continuous gapping is a positive test for both PLC and LCL injury, improved stability suggests an isolated LCL injury.

External Rotation Recurvatum Test:

This test evaluates the posterolateral rotary stability of the knee. In the supine position, the patient lies. The examiner next lifts the big toe off the table, rotates the tibia externally with the other hand, and applies a downward push via the suprapatellar region. An LCL injury is indicated by excessive hyperextension relative to the uninjured knee, which is a good exam result. Interestingly, this test is more reliable in diagnosing related ACL injuries but less than 10% accurate in recognizing PLC injuries.

Posterolateral Drawer Test:

The knee is externally rotated 15 degrees and flexed 90 degrees while the patient is in the prone position. The femoral condyles are subsequently given a posterior force by the examiner. A PLC injury is indicated by excessive posterolateral translation, which is a positive test result.

Reverse Pivot Shift:

The posterolateral drawer test and this test are conducted in the same manner. The examiner applies an external rotating force and valgus to the knee while progressively extending it, while keeping an eye on the lateral joint line. The ITB reduces the previously subluxated lateral tibial plateau at 90° by changing from a flexion to an extension vector at 30°. If there is an audible click at 30°, the test is positive, and there is posterolateral rotatory instability due to combined ACL and PCL injuries. Because a significant portion of knees that are not damaged may produce false-positive results, results must be compared bilaterally.

Dial Test:

This test helps verify PLC damage and evaluate external femoral rotation. The patient is in a prone position. After stabilizing the thigh with one hand, the examiner rotates the ankle and leg externally with the other. Bilateral knee flexion tests are conducted at 30° and 90°. PLC damage is confirmed by external rotation of at least 10° on the affected leg.

To prevent excluding related ligamentous, meniscal, or soft tissue injuries, which are quite likely to occur in trauma cases, knee exams should be understand and include all articular components. To rule out potential ACL or PCL problems, anterior and posterior drawer tests are required. Patellar evaluation aids in the detection of concomitant dislocation or subluxation.

Classification of Injury:

Depending on their severity, LCL injuries are divided into three grades.

Grade I: Mild Sprain

- Mild lateral collateral ligament pain and tenderness.

- Typically, there is no edema.

- Although the varus test at 30° is uncomfortable, there is no laxity (less than 5 mm).

- There are no signs of instability or mechanical issues.

Grade II: Partial Tear

- The lateral and posterolateral sides of the knee are quite tender and painful.

- Inflammation near the ligament,

- There is joint laxity with a definite endpoint, and the varus test is unpleasant.

Grade III: Complete Tear

- Compared to grade II, the pain may be less severe or varied.

- Pain and tenderness at the injury site and on the side of the knee

- Significant joint laxity (>10mm laxity) is revealed by the varus test.

- Subjective instability.

- Significant swelling.

Diagnostic Imaging:

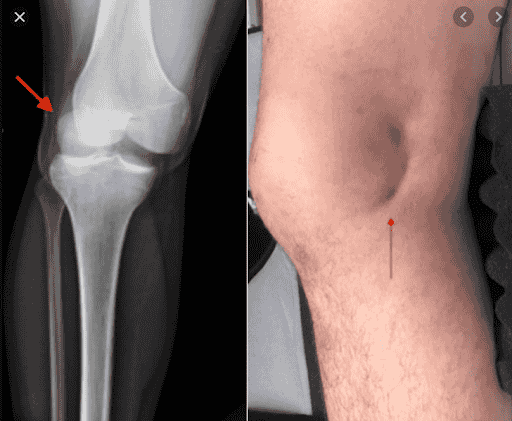

- Radiograph: Additional research on the LCL is necessary if there is a noticeable arcuate sign or segment fracture, which is suggestive of PLC damage. The degree of LCL and PLC injuries is assessed using varus and posterior kneeling stress imaging. LCL alterations cannot be seen on simple lateral and anteroposterior knee radiographs. To rule out related structural injuries, X-rays are required. Avulsions of the tibial spine, lateral tibial plateau (Segond fracture), and fibular head fractures or avulsions (arcuate sign) are common radiographic abnormalities. Further workup for LCL injury is warranted because the arcuate sign and Segond fracture are pathognomonic for PLC injury. When older people have persistent lateral knee pain, plain radiographs can help rule out underlying arthritic changes. Additionally required are varus and kneeling posterior-stress radiographs. Both have great user reliability and can display the severity of LCL and PLC injuries.

- MRI is regarded as the gold standard for identifying PLC and LCL injuries. The sensitivity and specificity of coronal and sagittal weighted T1 and T2 scans to detect an LCL injury are 90%.

The most reliable method for identifying structural LCL and PLC injuries is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). At almost 90%, the highest sensitivity and specificity for LCL injury are found in coronal and sagittal T1- and T2-weighted series. However, radiographs and a thorough physical examination are still necessary to establish whether surgery is necessary based only on MRI results.

LCL injuries can be promptly detected by musculoskeletal ultrasonography. Hypoechogenicity and LCL thickness are indicators of damage. Edema, dynamic laxity, or a loss of LCL fiber continuity can all be signs of a full tear. - Ultrasound: An effective method for obtaining a quick diagnosis of LCL damage is ultrasound. If the LCL is swollen and hypoechoic, examination may reveal LCL damage. An ultrasonography may reveal increased edema, dynamic laxity, and/or a loss of LCL fiber continuity if there is a complete tear.

Treatment of Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury:

Medical Treatment:

Non-surgical techniques are used in conservative treatment for an LCL injury in order to control pain, minimize swelling, and encourage recovery. Common conservative therapies for an LCL injury include the following:

- Rest: For the knee to heal, rest is essential. Limit weight-bearing activities and stay away from painful or uncomfortable activities.

- Ice: Using ice to treat the knee might help lessen pain and swelling. Ice should be applied several times a day for 20 minutes at a time.

- Compression: Using a brace or compression bandage might assist in supporting the knee and lessen swelling.

- Elevation: One way to lessen swelling is to raise the damaged leg above the level of the heart.

- Exercises to increase knee strength and range of motion can be performed with the assistance of a physical therapist.

- Medication: Acetaminophen and ibuprofen are examples of over-the-counter pain medications that can be useful in lowering inflammation and pain.

- Injection therapy: To lessen knee pain and inflammation, corticosteroid injections may be utilized.

For isolated grade 1 or 2 injuries that do not exhibit instability at 0°, nonoperative therapy is recommended. For optimal pain management, patients should wear crutches and avoid from bearing any weight for a week. To stabilize the knee medially and laterally throughout functional rehabilitation, the patient should wear a hinged knee brace for three to six weeks. Recovery depends on early progressive rehabilitation and little immobility. In 6 to 8 weeks, patients typically resume their athletic activities. In order to prevent PLC injuries from being overlooked during follow-up, which could lead to increasing varus and hyperextension laxity, the affected knee must be carefully evaluated.

After MRI-documented isolated grade 3 LCL injuries were treated nonoperatively, Bushnell et al. observed that National Football League athletes quickly returned to playing at the professional level. For the majority of grade 3 LCL tears, however, surgery is still the accepted course of treatment.

When anatomic reduction with full knee extension is possible, surgical repair is recommended for a grade 3 LCL tear that is isolated acutely (i.e., ≤ 2 weeks postinjury) and has an avulsed ligament from its attachment point. A mid-ITB lateral incision, dissection of the common peroneal nerve, biceps femoris bursal incision, identification of the LCL, and ligamentous reapproximation with a stay suture are all part of the procedure. The integrity of the LCL’s proximal femoral origin and the possibility of primary repair are next evaluated. After that, the ITB is dissected distally from Gerdy’s tubercle and proximally from the lateral epicondyle. The LCL is reattached to the femoral footprint using a suture anchor if the femoral connection is avulsed. Surgical LCL repair has been associated with a high failure rate of up to 40%.

In subacute cases, chronic (i.e., more than two weeks after the injury) or acute total midsubstance tears, surgical reconstruction of isolated grade 3 LCL tears is recommended. Varus instability is frequently chronic in these situations. Acute LCL avulsion with unattainable anatomic reduction, such as in situations involving severe trauma to adjacent structures, is another indication. The same repair approach should be used to treat concurrent knee injuries.

It is crucial to remember that not all LCL injuries can benefit from conservative therapy, particularly if they are severe or involve additional knee conditions. Surgery might be required in certain situations to rebuild or repair the LCL. To find the best course of therapy for your particular injury, it is crucial to speak with a medical practitioner.

Grades 1 and 2: Rest, ice, compression, and NSAIDs are effective acute treatments for grade 1 and 2 LCL injuries. For grade I or II sprains, conservative treatment of LCL injuries is most frequently used. To preserve medial and lateral stability throughout functional rehabilitation, patients should be non-weightbearing for the first week and remain in a hinged brace for the next three to six weeks.

Grade 3: Rest, ice, compression, and NSAIDs are also recommended for the acute treatment of a grade 3 LCL injury. Grade III sprains are more serious and may also cause damage to the posterolateral corner, anterior cruciate ligament, or posterior cruciate ligament. In this instance, surgery is required to stop the knee joint from becoming even more unstable. According to recent research, the best course of treatment for grade 3 LCL injuries is reconstructive surgery, which aims to restore a stable, properly aligned knee with normal biomechanics. Rebuilding the LCL with a semitendinosus autograft is the surgical treatment for isolated LCL injury.

For the first six weeks following surgery, a change in weight-bearing status may be necessary. This is probably just partially weight-bearing, but could become non-weight-bearing after substantially more surgery. A knee immobilizer can also be used to prevent the knee from flexing during locomotion and to reduce valgus/varus strains on the knee. It is recommended that early range-of-motion exercises be performed without bearing any weight. Normal rehabilitation, as outlined in the physical therapy management, can begin following the initial post-operative phase. It is helpful to remember that deep squats should be avoided for the first four months if a meniscal repair is also performed.

Physical Therapy Treatment:

Although a milestone-based approach can be used for ACL repairs or ruptures, as with other ligament injuries, rehab programs should be designed with normal soft tissue recovery timelines in mind.

Acute Treatment:

- POLICE or RICE

- Analgesia

- Oedema (swelling) management

- bracing in the form of an adjustable brace or knee immobilizer that permits full extension but restricted flexion.

- Early knee mobilization should be promoted.

- Quadriceps activation exercises

- Make sure your leg raises straight and without lag.

- Additionally, electrical stimulation can stop muscle atrophy caused by immobilization.

Sub-Acute Treatment:

- Full weight-bearing gait education.

- Full AROM of the knee

- Closed chain strength work

- Improvement in quadriceps, glutes, gastrocnemius, and hamstring strength training.

Long-Term Treatment:

- Proprioception work

- Aerobic conditioning

- Plyometric workouts that target excessive external tibial rotation or varus.

- High-level loading and reinforcement of the entire kinetic chain.

In order to encourage healing, lessen pain and inflammation, and enhance knee function, physical therapy treatment for an LCL injury usually combines exercises and manual therapy approaches. Common physical therapy interventions for an LCL injury include the following:

- Exercises for range of motion: These exercises aid in increasing the knee joint’s flexibility and range of motion. Ankle pumps, heel slides, and knee bends are a few examples.

- Strengthening exercises: The quadriceps, hamstrings, and calf muscles, which support the knee joint, become stronger with these workouts. Squats, leg presses, and calf lifts are a few examples.

- Exercises that enhance balance and proprioception can lower the chance of re-injury by enhancing coordination and balance. Step-ups, wobble board workouts, and single-leg stands are a few examples.

- Techniques for manual therapy: These methods are intended to lessen knee joint pain and inflammation. Stretching, massage, and joint mobilization are among examples.

- Modalities: To lessen knee pain and inflammation, modalities like electrical stimulation, ultrasound, and ice or heat therapy may be employed.

- To improve total knee function, functional training involves performing targeted exercises that replicate the motions needed for daily tasks or athletic endeavors.

The severity of the injury, as well as personal characteristics like age, degree of activity, and general health, will determine the particular physical therapy treatment approach. Working closely with a physical therapist is crucial to obtaining a customized treatment plan that meets your unique needs and objectives.

Surgical Treatment:

LCL Reconstruction Approaches:

There are three types of LCL reconstruction techniques: isometric, nonanatomic, and anatomic. The particulars of the damage, the patient’s functional needs, and the surgeon’s experience all influence the decision between nonanatomic, isometric, and anatomic restoration.

Isometric tenodesis:

The Clancy approach involves making a posterolateral knee incision and drilling a hole just in front of the femoral attachment of the LCL in order to perform isometric tenodesis, also known as biceps femoris tenodesis. To make 0.5 inches noticeable, put a 6.5 mm screw with a spiked washer. The posterior intermuscular septum splits, moving the biceps tendon to a position anteromedial to the ITB.

The knee is 90 degrees flexed. The tendon is then levered over the screw post with a slow extension of the knee. The screw with the washer is fastened once it reaches full extension. After that, the ITB is closed. To identify any tendon subluxation or ITB snapping, the range of motion should be evaluated repeatedly throughout the treatment.

Isometric LCL reconstruction:

Patellar tendon allograft was described as a nonanatomic procedure. All soft tissues are removed from the proximal fibula. After that, a tunnel is dug and progressively widened via reaming. A midline incision in the ITB exposes the femur, and a tunnel is bored 6 mm in front of the LCL femoral insertion location. The medial femoral epicondyle should be in front of and proximal to the tunnel. Using a looped suture and a tiny K-wire, the surgeon may verify isometry.

An interference screw is used to shape and bind the graft to the fibula before it is pushed through the femoral tunnel. After applying valgus stress and tensioning the graft with the knee at 20° to 30° of flexion, it should be secured with an additional interference screw. The literature has documented a number of additional isometric LCL restoration methods using different grafts, including the Achilles tendon graft.

Anatomic LCL reconstruction:

A biomechanical investigation confirmed that isolated repair with a semitendinosus graft restored exact knee biomechanics. Laprade used a semitendinosus transplant to explain the anatomical method.

At the location of the fibular LCL insertion, a fibular head.. A second tube is then drilled through an ITB split at the femoral connection site. An interference screw is used to anchor the graft into both tunnels while applying valgus tension and 20° of knee flexion. After that, the graft is evaluated for secure attachment and function confirmation. Lastly, for an enhanced fixation, the graft is sutured to itself.

Prevention:

A knee injury, such as an LCL tear, cannot be prevented, but there are things you can do to lower your risk:

- When participating in sports, wear a knee brace to support your ligaments.

- When participating in sports, make sure your knees are in proper alignment. Find out from your doctor how to maintain the alignment of your knee while playing.

- Before training or games, stretch.

- Perform conditioning workouts to increase your flexibility and strength.

Be mindful of your knees. Doing additional stretches and exercises may seem time-consuming, but it’s worth it to maintain the health of your knees.

Prognosis:

LCL injuries can be treated surgically or nonoperatively, depending on their severity. With the right care, the prognosis for PLC and LCL injuries is favorable. High-grade injuries, however, can take more than four months to heal.

The severity of the injury and the treatment strategy selected will determine the prognosis for a Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL injury.

- Conservative treatment for mild (Grade I) LCL injuries, which includes rest, bracing, and physical therapy, usually results in healing in two to four weeks.

- It takes 4–8 weeks to recover from moderate (Grade II) LCL injuries with systematic rehabilitation in order to regain strength and stability.

- Severe (Level III) LCL Damage: Whole tears can take three to six months to heal, and they frequently need surgery and a rigorous rehabilitation regimen.

With the right care, most people recover completely, but serious injuries can leave knees stiff or unstable for a long time. Strength training and early recovery enhance long-term results and lower the chance of reinjury.

Prognosis is possible with LCL tear, just like with most injuries. Inform your healthcare practitioner of any of the following:

- A sensation of knee joint instability.

- A pop, or the sensation of the knee “giving out” or collapsing.

- Weakness, tingling, or numbness in your lower leg or knee.

- Rigidity.

- If you observe the knee joint grinding or crushing.

Complications:

Chronic pain and knee instability are the most frequent long-term consequences of undiagnosed LCL and PLC injuries. Peroneal nerve palsy is also reported to occur in about 35% of PLC injuries, most likely as a result of the nerve’s close proximity to the LCL. Patients may experience reduced sensation on the dorsal and lateral foot surfaces, lower extremity weakness, and chronic foot drop. In the meantime, stiffness and hardware irritation are frequent postoperative side effects in patients undergoing surgery.

- Chronic knee instability is characterized by the knee’s weakness and looseness, which makes it prone to giving way, particularly while moving laterally.

- Reduced Range of Motion: The knee becomes stiff and difficult to fully extend or flex.

- Persistent Pain and Swelling: Prolonged pain caused by secondary joint problems or inadequate healing.

- Increased Risk of Reinjury: Recurrent sprains or tears can result from weakened ligament structure.

- Associated Ligament or Meniscus Damage: Recovery from severe LCL injuries can be made more difficult if they affect the ACL, PCL, or meniscus.

- Long-term joint deterioration caused by instability and irregular knee mechanics is known as post-traumatic osteoarthritis.

- Nerve or Vascular Injury: Severe LCL injuries can occasionally impact the peroneal nerve, resulting in numbness or foot drop.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, especially in sports and active people, a Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) injury can have a major effect on knee stability and function. Determining the extent of the injury requires a proper diagnosis made via imaging and clinical evaluation. Conservative treatment for mild to moderate LCL injuries usually involves bracing, strengthening exercises, physical therapy, and rest. However, surgical intervention may be necessary in extreme cases, particularly those involving ligament tear or related injuries. Restoring knee strength and stability and avoiding further injuries requires early rehabilitation and a well-organized recovery strategy.

Athletes who suffer a tear in their lateral collateral ligament may be out for three to twelve weeks, or even longer. If you tear your LCL, you should see your doctor for a thorough evaluation, even if you might be eager to resume playing. Treatment, rest, and rehabilitation will help you recover and lower your chances of becoming hurt again. Discuss further knee protection measures with your healthcare provider.

FAQs

What is the LCL tear first aid protocol?

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines (NSAIDs), elevating the joint above the level of the heart, applying ice to the injury, and limiting physical activity until the pain and swelling go away are all part of the initial treatment for an LCL injury. While the ligament recovers, it should be protected using a hinged knee immobilizer.

How do I make my LCL stronger?

Slide of heels on a wall

The distance between your hips and the wall should be as near as it feels comfortable. Place both feet on the wall to begin. Allow your affected leg’s foot to slowly slide down the wall until your knee starts to stretch. For 15 to 30 seconds, hold.

Does LCL heal completely?

Rebuilding strength might take up to six weeks, but minor LCL ligament injuries heal in a few weeks. It takes four to eight weeks for a more severe tear (grade 3) to heal, and the recovery period is significantly longer.

Is it uncomfortable to touch the LCL?

The following are some signs of a lateral collateral ligament tear: swelling in the knees. grabbing or locking your knee as you move. Your knee may feel tender or painful on the outside.

When your LCL is injured, how do you sleep?

When you ice your leg or whenever you sit or lie down, support it with a pillow. After your injury, continue doing this for roughly three days. Aim to maintain your knee above your heart. This will lessen the edema.

How can an LCL injury be tested?

The most helpful specialized test for evaluating an LCL injury is the Varus Stress Test. A varus force is administered, paying particular attention to the lateral joint line, once the femur has stabilized. First, the test is conducted in a 30-degree flexion position.

Can someone with an LCL tear flex their knee?

Patients frequently have trouble bending their knees and experience severe pain and edema. When grade III LCL tear occur, instability, or giving out, is frequently observed. Surgical reconstruction is frequently necessary for grade III LCL tear.

How serious is an LCL tear?

You may have also injured other components of your knee if your LCL injury is more serious. Surgery might be required to repair your LCL and assist stabilize your knee if this occurs to you. Recovering from surgery and being able to bear weight on your knee can take up to four months.

Is surgery necessary for LCL?

The magnitude of the injury determines the course of treatment. Surgery and physical treatment may be necessary for severe LCL tear, which frequently occur in conjunction with additional knee injuries. Physical therapy alone usually works for less serious condition.

Can LCL fix itself?

The most important thing to do is to keep the ligament from becoming injured again while it heals. The ligament will repair itself. Range-of-motion exercises and mild strengthening of the quadriceps (thigh muscles) and biceps femoris (hamstring muscles) are recommended during the healing phase.

With an LCL tear, is it possible to walk?

You might not have any symptoms if your LCL injury is minor. You can feel pain, stiffness, edema, and instability if your LCL injury is more severe. The inability to walk is one of the additional signs of an LCL injury.

How does pain in the LCL feel?

The exterior of the knee is swollen, painful, and tender. walking with one knee bent or limping. When an injury occurs, there may be a popping, tearing, or pulling sensation. The knee feels like it’s giving out.

Is it possible to mend an LCL tear without surgery?

The lateral collateral ligament, or LCL, has a healthy blood supply and typically reacts favorably to non-surgical therapy. Grade 3 LCL tears may actually need surgery because they do not mend as well as MCL (medial collateral ligament) tears.

How is a lateral collateral ligament damage treated?

RICE (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) and NSAIDs are usually used as the first line of treatment for lateral collateral ligament (LCL) injuries. Depending on the extent of the damage, physical therapy and, in certain situations, surgery are next administered.

How much time does it take for an injury to the lateral collateral ligament to heal?

It is more likely to be torn by athletes, which can result in severe pain and other symptoms. Depending on how severe they are, LCL tears often heal in three to twelve weeks.

References

- LCL Tears. (2025, March 19). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21710-lcl-tears

- Yaras, R. J., O’Neill, N., Mabrouk, A., & Yaish, A. M. (2024, February 27). Lateral collateral ligament knee injury. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560847/

- Treatment. (2019, July 1). Stanford Health Care. https://stanfordhealthcare.org/medical-conditions/bones-joints-and-muscles/lateral-collateral-ligament-injury/treatment.html

- Leonard, J. (2023, July 27). What causes a lateral collateral ligament sprain? https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/323878

- Patel, D. (2023b, August 5). Lateral collateral Ligament (LCL) – anatomy, structure, function. Samarpan Physiotherapy Clinic. https://samarpanphysioclinic.com/lateral-collateral-ligament-lcl/