Hypoglossal Nerve

Introduction

The hypoglossal nerve is the 12th paired cranial nerve.

Its name is derived from ancient Greek, where ‘hypo’ means under and ‘glossal’ means tongue. Except for the palatoglossus, which is innervated by the vagus nerve, the nerve has a solely somatic motor function, innervating the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the tongue.

The hypoglossal nerve sheath in the neck receives a cervical plexus branch carrying fibres from the C1 and C2 spinal roots. These fibres branch off the hypoglossal nerve at various points, supplying a variety of neck muscles.

The nerve regulates the tongue’s ability to stick out and move side to side, which are necessary movements for speaking and swallowing. Damage to the nerve or the neural pathways that control it can impair the tongue’s ability to move and appearance, with the most common causes being trauma or surgery, as well as motor neuron disease.

Anatomical Course of Hypoglossal Nerve

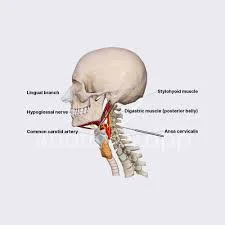

The hypoglossal nerve originates in the medulla oblongata of the brainstem, specifically the hypoglossal nucleus. It then moves laterally across the posterior cranial fossa, into the subarachnoid space. The nerve exits the skull through the hypoglossal canal of the occipital bone.

Now extracranial, the nerve receives a branch of the cervical plexus that conducts fibres from the C1/C2 spinal nerve roots. These fibres do not connect with the hypoglossal nerve; rather, they travel within its sheath.

After that, it travels inferiorly to the angle of the mandible, passing through the internal and external carotid arteries before coming out of the anterior and entering the tongue.

Embryology

Hypoglossal nerves are a type of cranial nerve originating from the brainstem’s somatic efferent column and similar to the spinal nerves’ ventral roots.

The 12th cranial nerve is formed by fusing the ventral root fibres of three to four occipital nerves. The CN XII common trunk is formed by the convergence of these nerve fibres, which begin in the hypoglossal nucleus and split off into tiny hypoglossal nerve roots on the ventrolateral side of the medulla. They develop rostrally until they come into contact with the muscles of the tongue. As the neck grows, the hypoglossal nerve gradually moves upward.

Nerves

The hypoglossal nuclei pair in the lower medulla is the source of the hypoglossal nerve. The two nerves emerge laterally and ventrally from their respective nuclei. The nerve divides in two before exiting the medulla and passing through the hypoglossal canal in the occipital bone of the skull. The nerve reforms and descends through the neck to the angle of the mandible, where it innervates the tongue muscles.

The nerve is below the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein, as well as near the vagus nerve, in the early stages of its course. The nerve then passes above the hyoid bone and between the mylohyoid and hyoglossus muscles before branching to different parts of the tongue musculature.

The function of the Hypoglossal Nerve

The tongue’s muscles are under the hypoglossal nerve’s control. The tongue has four extrinsic muscles that originate outside and are attached to it. The hypoglossal nerve regulates three of these. The tongue has intrinsic muscles:

- Genioglossus. This muscle originates in the lower jaw (mandible) and extends along the entire length of the tongue. It moves your tongue forward and lowers its central portion.

- Hyoglossus. It originates from the hyoid bone and connects to the side of your tongue. It’s the muscle responsible for pulling your tongue back and down. It also flattens the tongue.

- Styloglossus. This muscle attaches to the side of the tongue and comes from the temporal bone. This muscle moves the tongue up and down while pulling it back into the mouth.

- Intrinsic muscles. These muscles reside entirely within your tongue. They shorten the tongue, curl its tip, turn it downward, narrow and lengthen it, and flatten and widen it.

The only tongue muscle not supplied with innervation by the hypoglossal nerve is the palatoglossus. The vagus nerve, or cranial nerve 10, controls this muscle.

The thyrohyoid, omohyoid, sternohyoid, and sternothyroid muscles, which regulate the mandible (lower jaw) and hyoid bones during speech and swallowing, are also innervated by the hypoglossal nerve. The nerve fibres that travel with the hypoglossal nerve are derived from the first, second, and third cervical spinal nerves; therefore, this is not a true function of the hypoglossal nerve.

Examination of hypoglossal nerve

Damage to the hypoglossal nerve paralyzes the tongue. Typically, only one side of the tongue is affected, and when the person sticks out his or her tongue, it deviates or points to the damaged side.

The tongue is first examined for its position and appearance while at rest. The patient is then asked to protrude and move his tongue in and out, side to side, and up and down. The patient performs each movement twice: once slowly and then quickly. The tongue’s three distinguishable features are its strength, bulk, and dexterity.

Asking the patient to repeat sounds with their tongue, like “la la la” or words with “t” or “d” sounds, is how dexterity is measured. The examiner tries to move the tongue with his or her finger as the patient presses it against the patient’s cheek.

When the tongue is weak, atrophied, moving abnormally, or impaired, extra care is taken.

Conditions affect the hypoglossal nerve

The following conditions can affect this nerve:

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): In advanced stages, the hypoglossal nerve may be unable to communicate with the brain.

- Encephalitis: Inflammation can cause the brain stem to press against the hypoglossal nerve.

- Treatments for head and neck cancer may disrupt nearby tissue, including the hypoglossal nerve.

- Sleep apnea: The hypoglossal nerve regulates the muscles in the back of your throat. If they relax too much while sleeping, your tongue may slide out of position, obstructing the airway.

- Stroke: A lack of blood flow may impair the brain’s ability to communicate with the hypoglossal nerve.

- Trauma: Serious injuries, such as a stabbing, can sever the hypoglossal nerve.

Symptoms

If one of your hypoglossal nerves isn’t functioning properly, you may notice that your tongue deviates to one side when pushed out. Your speech may be disrupted because you need precise tongue movements to form syllables. Long-term nerve dysfunction can cause muscle atrophy on one side of the tongue, resulting in a wasted and smaller tongue.

Damage to just one hypoglossal nerve is unlikely to cause serious problems. The other hypoglossal nerve can typically compensate. However, if both nerves aren’t working, you’ll have trouble speaking and swallowing.

Fasciculations are flickering movements on the tongue’s surface that are associated with certain hypoglossal nerve disorders. Difficulty speaking or swallowing, tongue weakness, and fasciculations may indicate a serious condition such as nervous system disease or cancer. If you encounter any of these symbols, consult a physician.

Radiographic Features

The hypoglossal nerve is thought to be best evaluated using a segmental approach, with the choice of MRI or CT modalities informed by dividing the nerve into its constituent segments. MRI is the preferred modality for directly visualising a specific segment of the nerve, whereas CT is generally better at displaying the nerve’s course through the skull base.

The authors recommend tailoring the imaging technique to both the anatomical segment to be studied and the most common pathological entities affecting that segment.

Prevention

Hypoglossal nerve issues can impair your ability to eat, speak, and swallow. Some causes, such as trauma and surgical complications, are difficult to prevent. If you need a mouth or throat procedure, consulting an experienced surgeon may reduce your risk.

Taking care of yourself can help you avoid disrupting the hypoglossal nerve function. These efforts include the following:

- Following care instructions can help slow the progression of chronic conditions like ALS.

- Maintaining a healthy lifestyle to avoid a stroke.

- Maintaining a healthy weight can help you avoid or manage sleep apnea.

- Quitting smoking if you use tobacco and limiting your alcohol intake. These two can aid in preventing cancer of the head and neck.

Summary

The hypoglossal nerve is the 12th paired cranial nerve, responsible for innervating the tongue’s extrinsic and intrinsic muscles. It originates in the medulla oblongata of the brainstem and moves laterally across the posterior cranial fossa into the subarachnoid space. The nerve exits the skull through the hypoglossal canal of the occipital bone. After that, it travels inferiorly to the angle of the mandible, passing through the internal and external carotid arteries before coming out of the anterior and entering the tongue.

Hypoglossal nerves are a type of cranial nerve originating from the brainstem’s somatic efferent column and similar to the spinal nerves’ ventral roots. They form by fusing the ventral root fibers of three to four occipital nerves. The hypoglossal nerve regulates the tongue’s muscles, including the extrinsic muscles (Genioglossus, Hyoglossus, Styloglossus, and Intrinsic muscles) and the thyrohyoid, omohyoid, sternohyoid, and sternothyroid muscles.

Damage to the hypoglossal nerve can paralyze the tongue, with only one side affected. The patient is asked to protrude and move their tongue in and out, side to side, and up and down to examine the position and appearance of their tongue while it is at rest. The tongue’s distinguishable features are its strength, bulk, and dexterity.

Conditions that affect the hypoglossal nerve include Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), encephalitis, head and neck cancer treatments, sleep apnea, stroke, and trauma. Symptoms of hypoglossal nerve dysfunction include deviating to one side when pushed out, speech disruption, muscle atrophy, and difficulty speaking or swallowing.

Radiographic features of the hypoglossal nerve are best evaluated using a segmental approach, with MRI or CT modalities being recommended for specific segments. Prevention involves regular check-ups and regular examinations to ensure proper functioning of the hypoglossal nerve.

FAQs

What does the hypoglossal nerve connect to?

The Hypoglossal Nerve is the 12th Cranial Nerve (XII). It is primarily an efferent nerve serving the tongue musculature. The nerve emerges from the medulla and travels caudally and dorsally to the tongue.

What can cause damage to the hypoglossal nerve?

Tumours, strokes, infections, injuries, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis are all potential causes of hypoglossal nerve dysfunction. Individuals with hypoglossal nerve disorder have difficulty speaking, chewing, and swallowing. Doctors typically use magnetic resonance imaging and/or a spinal tap to determine the cause.

Is it hypoglossal motor or sensory?

The hypoglossal nerve is a motor nerve that supplies the tongue’s muscles. It originates in the medulla. Disorders of the hypoglossal nerve can cause tongue paralysis, which usually occurs on only one side.

What is the definition of hypoglossal weakness?

This condition also affects the nucleus of the hypoglossal nerve. Progressive bulbar palsy causes tongue muscle wasting, throat muscle weakness and difficulty swallowing speech impairment, and weak jaw and face muscles.

What is the hypoglossal nerve’s functional component?

The hypoglossal nerve is the 12th paired cranial nerve. Its name is derived from ancient Greek, where ‘hypo’ means under and ‘glossal’ means tongue. Except for the palatoglossus, which is innervated by the vagus nerve, the nerve has a solely somatic motor function, innervating the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the tongue.

References:

- The Hypoglossal Nerve (CN XII) – Course – Motor – TeachMeAnatomy. (2022, December 11). TeachMeAnatomy. https://teachmeanatomy.info/head/cranial-nerves/hypoglossal/#:~:text=The%20hypoglossal%20nerve%20is%20the,%2C%20innervated%20by%20vagus%20nerve).

- Kim, S. Y., & Naqvi, I. A. (2022, November 7). Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 12 (Hypoglossal). StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532869/

- Hypoglossal nerve. (2024, May 4). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypoglossal_nerve

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Hypoglossal Nerve. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21592-hypoglossal-nerve

- Hypoglossal Nerve. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Hypoglossal_Nerve

- Mehta, P. (2022, October 3). Hypoglossal Nerve: What to Know. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/oral-health/hypoglossal-nerve-what-to-know

- Hacking, C., & Gaillard, F. (2008, May 2). Hypoglossal nerve. Radiopaedia.org. https://doi.org/10.53347/rid-1483

- Dellwo, A. (2024, March 1). The Anatomy of the Hypoglossal Nerve. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/hypoglossal-nerve-anatomy-4691482

One Comment