Facial Nerve

Introduction

The facial nerve is also called the seventh cranial nerve (CN7). This nerve has two main functions. It transmits sensory information from the tongue and the inside of the mouth. CN7 specifically serves the tip of the tongue, accounting for roughly two-thirds. The nerve extends from the brain stem to the pons and medulla. This nerve also innervates facial muscles, controlling their contraction and expression.

Over its route, CN7 divides into multiple branches. The lacrimal gland, which secretes tears, the nasal cavity, and the sphenoid, frontal, maxillary, and ethmoid sinuses—skull cavities—are all served by the greater petrosal nerve. The stapedius muscle in the inner ear receives motor signals from one of the branches.

The sublingual glands, a significant salivary gland, and the submandibular glands, located beneath the floor of the mouth, are supplied by the chorda tympani branch. The chorda tympani also communicate taste perceptions from the tip of the tongue.

Most facial nerve problems involve paralysis, which is most commonly associated with Bell’s palsy. This condition, as well as other types of paralysis, can be caused by a viral infection or Lyme disease complications.

What is the facial nerve?

The facial nerve connects your brain to specific muscles in your face. It controls the muscles that allow you to make expressions such as raising your brow, smiling, or frowning. This nerve is also linked to the tongue’s sensations of taste.

Anatomical Course

The facial nerve’s course is extremely complex. Numerous branches transmit a variety of sensory, motor, and parasympathetic fibres.

Anatomically, the course of the facial nerve is divided into two parts:

- Intracranial – the path of a nerve through the cranial cavity and the cranium.

- Extracranial refers to the nerve’s course outside the skull, through the face and neck.

Intracranial

The nerve originates in the pons, a part of the brainstem. It starts with two roots: a large motor root and a small sensory root (the part of the facial nerve that emerges from the sensory root is sometimes called the intermediate nerve).

The inner acoustic meatus, a 1 cm-long aperture in the petrous region of the temporal bone, is where each of the two roots enters. These are extremely near to the inner ear.

Further inside the temporal bone, the roots emerge from the internal acoustic meatus and go into the facial canal. The canal is a ‘Z ‘-shaped structure. Three major events take place within the facial canal:

First, the two roots combine to form the facial nerve.

The nerve then forms the geniculate ganglion, a collection of nerve cell bodies.

Finally, the nerve leads to:

The greater petrosal nerve carries parasympathetic fibres to the mucous glands and lacrimal glands.

Motor fibres connect the nerve to the stapedius muscle in the middle ear.

The Chorda tympani contains sensory fibres for the tongue’s front two-thirds along with parasympathetic fibres for the submandibular and sublingual glands.

The stylomastoid foramen is where the facial nerve ends the facial canal and cranium. This exit is located just posterior to the temporal bone’s styloid process.

Extracranial

The facial nerve exits the skull and runs superior to the outer ear.

The posterior auricular nerve was the first extracranial branch to arise. It supplies motor innervation to some of the muscles surrounding the ear. Motor branches are sent to the digastric muscle’s posterior belly as well as the stylohyoid muscle.

The nerve’s main trunk, also known as the motor root of the facial nerve, extends both anteriorly and inferiorly to the parotid gland (note that the glossopharyngeal nerve, not the facial nerve, innervates the parotid gland).

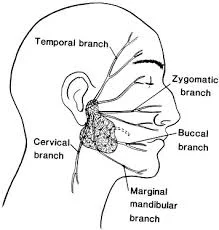

Within the parotid gland, the nerve branches into five different directions:

- Temporal branch

- Zygomatic Branch

- Buccal Branch

- Marginal mandibular branch.

- Cervical Branch

These branches innervate the facial expression muscles.

Embryology

During the 3rd week of the embryo, the bioacoustic primordium grows, and that structure eventually gives rise to the facial nerve. During the fourth week of life, the facial nerve divides into two parts: the chorda tympani and the caudal main trunk.

The geniculate ganglion and nervus intermedius emerge in the fifth week. The facial muscles emerge from the second branchial arch during their seventh and 8th weeks. Between weeks 10 and 15, the peripheral segment of the facial nerve undergoes extensive branching. From the 16th week to birth, the bony canal undergoes ossification.

Branches of the facial nerve

The facial nerve then enters the parotid gland and divides into five sections (see above). The facial nerve has five main branches, though the anatomy varies slightly between individuals. The branches are listed from top to bottom: frontal (or temporal), zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical. Each of these branches sends signals to a specific set of facial expression muscles.

The following is a rough guide to which areas each branch innervates. There is some “cross-talk,” or circuitry overlap, between branches.

- Frontal (temporal): Muscles of the forehead

- Zygomatic: Muscles involved in forceful eye closure.

- Buccal: The muscles responsible for moving the nose, upper lip, spontaneous eye blinking, and raising the corner of the mouth to smile.

- Marginal mandibular branch: the facial muscles that depress the lower lip.

- Cervical: The lower chin muscle (platysma) is frequently tense during facial hair shaving. Additionally, it brings your mouth’s corner down.

Functions of the facial nerve.

Special visceral efferent fibres

The facial nerve has particular visceral efferent or branchiomotor fibres that supply the flattened skeletal muscles of the face and scalp, the stapedius muscles of the middle ear, the digastric muscle’s posterior belly, and the stylohyoid muscle. They are neurons, with cell bodies located in the motor neurons of the facial nerve.

General visceral efferent (GVE) fibres

The general visceral efferent fibres in the facial nerve are involved in the parasympathetic component of the autonomic nervous system and play an important role in the innervation of lacrimal, nasal, or palatine glands, along with the submandibular or sublingual glands. They are neurons whose cell bodies are located in the superior salivary nucleus.

General somatic afferent (GSA) fibres.

General somatic afferent (sensory) fibres from neurons with cell bodies in the geniculate ganglion innervate the skin around the external acoustic meatus and the retroauricular region. They form synapses with second-order neurons in the trigeminal nerve’s principal sensory nucleus.

Special visceral afferent (GVA) fibres.

Last but not least, the facial nerve (chorda tympani branch) serves a unique sensory function by carrying special visceral afferent fibres that convey taste sensation from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue to the soft palate. They are neurons with cell bodies in the geniculate ganglion and synapses in the nucleus of the solitary tract.

Which problems and diseases affect the facial nerves?

Several conditions can cause weakness or paralysis of the facial nerve, such as:

- Accidents can lead to facial fractures.

- Bell’s palsy is an irritation of the facial nerve.

- Cancers such as salivary gland cancer and meningioma (skull base tumour).

- Ear infections or tumours, such as acoustic neuromas and schwannomas.

- Facial surgery includes cosmetic procedures such as facelifts.

- Guillain-Barré syndrome is an autoimmune disease.

- Lyme disease.

- Nerve blocks are used for dental procedures as well as neuropathy.

- Ramsay Hunt syndrome (a neurological disorder caused by infection with the chickenpox or shingles virus).

- Sarcoidosis.

- Stroke.

What signs indicate facial nerve paralysis?

The symptoms of facial nerve paralysis vary according to the cause. The symptoms could be temporary or permanent. You might experience:

- Unclear or slurred speech.

- Drooling, food coming out of your mouth, and difficulty eating and drinking.

- Drooping brow on the affected side of your face.

- Facial twitches (tic).

- Inability to move facial muscles such as the forehead, brow, and corner of the mouth.

- A lopsided smile or facial appearance.

- Loss of smell or taste.

- Nasal blockages.

- You’re having trouble closing or blinking your eyes.

- Sounds from your ear are amplified on the affected side of your face.

Impairment of the branches of the facial nerve

Frontal: Frontal paralysis is the inability to move the brow. Typically, this means the brow ‘hangs down’ in front of the eye, which can impair vision.

Zygomatic: Difficulties with forced eye closure.

Buccal: Difficulty smiling or moving the mouth. This causes problems with speech, particularly for sounds like “bee” and “papa,” which require precise lip motion to articulate. Food or liquid may drop out of the mouth unexpectedly due to abnormal lip movement. Furthermore, nasal obstruction on the affected side may occur due to paralysis of the muscles that keep the nostril open, resulting in an obstructed nostril. Normal blinking could be slowed or absent.

Marginal mandibular: The muscles innervated by the marginal mandibular are involved in the downward motion of the mouth corner. Injuries here can cause an asymmetric smile as well as eating and drinking issues.

Cervical: This is probably the least important of the branches. Damage on this nerve paralyses the platysma muscle, which is a thin sheet that lies just below the skin. Some patients may develop lower lip asymmetry when they smile.

Summary

The facial nerve, also known as the seventh cranial nerve (CN7), transmits sensory information from the tongue and mouth, mainly serving the tip of the tongue. It extends from the brain stem to the pons and medulla and innervates facial muscles. The nerve divides into multiple branches, including the greater petrosal nerve, which serves the lacrimal gland, the stapedius muscle in the inner ear, and the chorda tympani branch, which communicates taste perceptions. Most facial nerve problems involve paralysis, often associated with Bell’s palsy.

The facial nerve, a part of the human body, is formed during embryonic development. It is separated into frontal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical branches. Each branch sends signals to specific facial expression muscles.

The facial nerve has special visceral efferent fibers that supply facial muscles, general visceral efferent fibers that innervate glands, general somatic afferent fibers that innervate skin, and special visceral afferent fibers that convey taste sensation. Several conditions can cause facial nerve weakness or paralysis, including accidents, cancers, ear infections, facial surgery, autoimmune diseases, and sarcoidosis.

Facial nerve paralysis can cause symptoms like slurred speech, difficulty eating and drinking, a lopsided smile, loss of smell or taste, nasal blockages, and difficulty closing or blinking eyes. It affects the frontal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical branches of the facial nerve, affecting vision, speech, and eating and drinking.

FAQs

What causes facial paralysis?

Bell’s Palsy is the most common cause of facial paralysis, but it is only diagnosed after all other possible causes have been eliminated. Stroke, Lyme disease, Ramsay Hunt syndrome, brain tumours, head and neck tumours, trauma, surgery, and congenital abnormalities are all potential causes of facial paralysis.

What are the symptoms of facial paralysis?

Symptoms of facial paralysis are:

Facial weakness.

Facial asymmetry.

Difficulty with facial expressions, including smiling and blinking.

Difficulty closing eyes.

Changes in tear and saliva production

Taste changes in one side of the mouth.

sensitivity to loud sounds.

Pain near the ear on the affected side of the face.

How can you tell if your facial nerve is damaged?

People suffering from facial nerve damage may experience a variety of symptoms. The most common symptom is facial paralysis. Facial paralysis can leave a patient unable to move their facial muscles or perform involuntary facial movements.

How many facial nerves are present?

This nerve next arranges at the pes anserinus, forming the upper and lower divisions of the facial nerve. It then divides into five branches (temporal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical), which innervate the muscles of facial expression.

Where is the facial nerve located?

The chorda tympani branch of the facial nerve innervates the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, giving it a unique sense of taste. The nerve originates in the facial canal and travels across the middle ear bones before exiting through the petrotympanic fissure and entering the infratemporal fossa.

What is the function of the facial nerve?

The facial nerve is the seventh cranial nerve and contains nerve fibres that control facial movement and expression. The facial nerve also transports nerves that control taste to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue and produces tears (lacrimal gland).

References:

- The Facial Nerve (CN VII) – Course – Functions – TeachMeAnatomy. (2023, July 20). TeachMeAnatomy. https://teachmeanatomy.info/head/cranial-nerves/facial-nerve/

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Facial Nerve. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/22218-facial-nerve

- Facial nerve. (2018, January 23). Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/human-body-maps/facial-nerve#1

- Facial nerve (cranial nerve VII). (2023, October 30). Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/facial-nerve

- What is the Facial Nerve? (n.d.). Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery. https://med.stanford.edu/ohns/OHNS-healthcare/facialnervecenter/about-the-facial-nerve.html

- Seneviratne, S. O., & Patel, B. C. (2023, May 23). Facial Nerve Anatomy and Clinical Applications. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554569/

4 Comments