Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL) Injury

What is an Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL) Injury?

The Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL) runs along the front of the spine, providing stability and preventing excessive extension (backward bending). Injury to the ALL often occurs due to hyperextension trauma, such as whiplash from car accidents or sports injuries.

Symptoms may include pain, stiffness, and limited spinal movement, particularly in the neck or lower back. Treatment typically involves rest, physical therapy, and anti-inflammatory measures, with severe cases potentially requiring surgical intervention.

An injury to the ALL may result in excessive strain on the posterior disks and facet joints in the rear of the neck. Depending on the extent of ligament damage and the locations that are being irritated, each person may have different symptoms.

A headache, pain, numbness or tingling in one or more arms, lightheadedness, dizziness, and neck and shoulder stiffness and spasms are common symptoms. Looking up usually makes the symptoms worse.

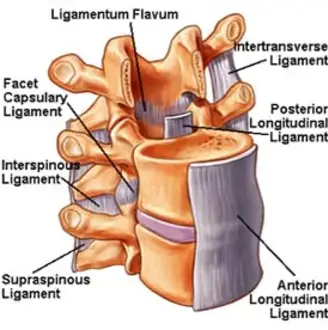

Anatomy of Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL) Injury:

Along the anterior side of the spinal column’s vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs, the Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL) extends vertically. By preventing the spine from extending too much (bending backward), it offers stability. Its clinical importance in spinal health and rehabilitation after trauma or degenerative disorders is highlighted by the fact that injury to the ALL can result in spinal instability and deformity.

Causes of Anterior Longitudinal Ligaments Injury:

Among the most frequent causes of Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL) injuries are abrupt traumas like falls and auto accidents. In certain instances, spinal alignment may also be impacted by degenerative diseases.

- Trauma: An injury can result from trauma to the Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL), which includes abrupt, powerful hits to the spine from falls, sports injuries, and auto accidents. These incidents have the potential to cause pain, instability, and long-term spinal issues by tearing or stretching the ligament.

- Degenerative Changes: The Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL) gradually deteriorates as a result of aging or diseases like osteoarthritis. These disorders may result in ligament deterioration that impairs spinal stability. Additionally, this may result in stiffness, decreased spine mobility, and persistent pain.

- Repetitive Strain: Repetitive lifting or bending exercises can put stress on the ALL, which over time may result in inflammation or microtears. An ALL tear may become more likely as a result of the ligament being weaker.

- Poor Posture: Long-term bad postures, such as hunching or slouching, improper seating, or not utilizing mattresses that support the spine, can produce structural changes in the spine, such as misalignment or increasing curvature (kyphosis), which over time can result in ALL problems.

- Underlying Conditions: Over time, certain medical diseases such as ankylosing spondylitis or rheumatoid arthritis can impair the stability and integrity of the spine, making it more vulnerable to ALL damage.

Symptoms of Anterior Longitudinal Ligaments Injuries:

Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL) injuries can have a range of symptoms depending on the underlying cause. However, back pain is typically one of the more prevalent complaints, particularly when the back is stretched. Other symptoms include stiffness, decreased flexibility, and even instability of the spine.

- Pain: Localized pain throughout the spine from ALL traumas might get worse depending on the movement, like leaning back. Depending on the extent of the damage, pain can range from dull to acute and may radiate to other parts of the chest or back.

- Stiffness: ALL injuries frequently cause stiffness in the spine, especially when doing activities that call for spinal extension. It may reduce flexibility and range of motion, making smooth motions like twisting or bending painful.

- Muscle Spasms: Muscle spasms are caused by ALL injuries as the body tries to shield the damaged ligament. These spasms can occur quickly, causing movement restriction and more pain. They may appear along the back, where the body adjusts for the movement and there is a lot of stiffness.

- Limited Range of Motion: Because ALL injuries limit the spine’s ability to bend or be flexible, they frequently result in a decreased range of motion, particularly when backward bending or when attempting to straighten the back. Frequently, pain that radiates through the back follows the stiffness.

- Radiating Pain: When the torn ligament or related tissues compress surrounding nerves, it can cause numbness, tingling, or shooting pain along nerve pathways. This is why radiating pain from the spine into the arms or legs is a common indicator of an ALL injury.

- Numbness or Tingling: Compression of spinal nerves by ALL injuries can cause tingling or numbness in the places those nerves service. This symptom, which can disrupt feeling and possibly result in weakening in the affected limbs, might appear in the back, buttocks, or down the legs (sciatica).

Diagnosing of Anterior Longitudinal Ligaments Injuries:

An accurate diagnosis of an anterior longitudinal ligament injury requires a combination of physical examination, imaging techniques (such as MRIs or X-rays), and symptom assessment. This aids in determining the extent of the injury and the impacted areas, enabling your healthcare provider to create the most effective treatment strategy.

- X-ray: X-rays are helpful because they offer preliminary imaging of the spine, which can be used to check for degenerative disorders affecting the Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL), fractures, and changes in alignment. This aids in understanding the state and function of the bones, which are essential for both strength and mobility.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI helps provide fine-grained images of soft tissues, including the ALL, by using radio waves and magnetic fields. This may precisely detect spinal cord anomalies, disc herniations, and ligament injuries, all of which aid in the diagnosis of ALL injuries. This aids in understanding the function and state of the muscles and tissues, which an X-ray might not be able to reveal.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: CT scans produce cross-sectional images of the spine using X-rays and computer technologies. These pictures include close-ups of bone structures and help identify any fractures, anomalies in the bones, or spinal disorders that may be affecting the ALL.

- Ultrasound: Real-time images of the soft tissues and ligaments in the spine are produced via ultrasound imaging using sound waves. Despite being less frequently utilized for spine imaging than MRI or CT, it can offer important insights about ALL injuries, particularly in certain clinical contexts or in situations when other modalities are not conclusive.

Ligament injuries occur into all three categories:

- Grade 1: A minor partial tear or mild straining of the ligament that is less than 50% of its width.

- Grade 2: More than 50% of the ligament fibers are torn, indicating moderate ligament damage.

- Grade 3: Total ligament rupture. Complete tears may not retract, which means that the ligament’s fibers are still roughly in contact with one another. Ligament fibers that are pulled apart are referred to as completely retracted tears.

Treatment of Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL) Injury:

Medical Treatment:

In order to improve spinal stability and mobility, Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL) injuries, like the majority of injuries involving muscles and bones, require rest and physical therapy. Common treatment options for ALL injuries include pain management with drugs or injections and, in extreme situations, surgery to stabilize or reconstruct the spine.

The degree of the damage and any further structures that may be harmed determine how ALL injuries are treated.

- Conservative care is usually sufficient for grade 1 injuries.

- Minimally invasive techniques can be employed to further encourage repair for grade 2 injuries and grade 1 injuries that do not heal completely.

- Surgery is frequently necessary for grade 3 injuries.

At-Home Remedies for Mild ALL Injuries:

Although consulting a medical practitioner is essential, there are also several at-home treatments you can attempt to aid in your recovery.

Rest:

Limit painful activities, such as extending your neck. In general, you should reduce some of your neck’s motions and move it more slowly rather than completely resting in bed or ceasing to move it at all.

Ice or heat application:

Ice can temporarily relieve sore spots and aid with swelling. Ice should only be applied for brief periods of time since too much cooling might decrease blood flow, which is essential for healing.

Heat therapy, particularly infrared heat, can ease pain, ease tense neck muscles, and increase blood flow. Regular heating pads can burn skin, so use caution while using them to avoid overheating or leaving them in one place for an extended period of time.

Activity modification:

Adjust activities to prevent excessive neck strain. No contact sports, high-intensity exercise, or quick neck motions.

Stretching:

Maintaining normal joint motion is beneficial for joint health and can be achieved with mild neck stretching and mobilization. Additionally, stretching can aid in the relaxation of tense muscles.

Pain Medications:

In the event that home treatments are ineffective for treating anterior longitudinal ligament injuries, pain medicines may be prescribed.

- Non-prescription and prescription medications:

Pain management and inflammation reduction may be aided by over-the-counter pain remedies like Tylenol and anti-inflammatory drugs like Aleve, Ibuprofen, and others. For more severe pain, a doctor may occasionally prescribe strong painkillers.

Although non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines (NSAIDs) might help reduce pain, their usage should be limited due to their numerous possible adverse effects. Possible adverse effects include gastrointestinal bleeding, upset stomach, liver or renal issues, elevated risk of heart attack or stroke, and slowed recovery.

Oral steroids are rarely if ever, used for the majority of musculoskeletal problems unless there is spinal cord damage. They are occasionally administered for severe inflammation. The hazards of steroids are considerably greater than those of NSAIDs; these include the loss of bone, changes in hormone function, changes in blood sugar, weight gain, transient psychosis, and the inhibition of healing.

In cases of extreme pain, narcotic painkillers may be utilized. Naturally, there are a lot of hazards associated with them, including addiction, fatigue, constipation, respiratory depression, cognitive impairment, and even worsening pain.

- Pain injections:

Although the ALL can occasionally cause direct pain, it usually results in pain in the neck disks or joints or irritates the nerves.

Steroids and a local anesthetic can be injected into these joints to relieve pain and lessen inflammation. In addition to providing pain relief for weeks or months, this can be used for diagnostic purposes. Naturally, this is only short-term assistance; it doesn’t treat the damaged ALL, and as was already mentioned, steroids carry a number of hazards.

In a treatment known as an MBB, the medial branches of the nerves that innervate the joints can be blocked with a local anesthetic to relieve joint pain. This would aid in the diagnosis of facet joint pain, and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) might be carried out if it helped for a few hours. An RFA may provide pain relief for six to twelve months at a period because it burns the nerves that innervate the joints.

The fact that this is still merely a short-term pain reliever and does not treat the damaged ALL are the drawbacks. Additionally, since those nerves also control the muscles that stabilize the neck, they will weaken and shrink (atrophy), which will increase neck instability.

An epidural injection of local anesthesia and/or steroids can be used to treat nerve pain. Once more, this has all the hazards associated with steroids and can be used for diagnostic purposes as well as for short-term pain relief. However, it does not treat the ALL damage.

Physical Therapy Treatment:

There are a number of rehabilitation strategies to take into account for people with ALL injuries. Orthotic devices and physical therapy are essential for promoting healing and enhancing quality of life.

One of the most crucial forms of treatment for ALL injuries is physical therapy. Poor shoulder and neck posture should be addressed by good physical therapy, which can also aid in maintaining or increasing neck mobility and range of motion as well as help to develop or preserve neck strength. Additionally, PT offers techniques for pain management, muscular relaxation, and other purposes. By relieving further strain on the neck and ALL, promoting healing, and lowering the chance of further harm, all of these can aid in the body’s natural healing process.

Bracing:

- When there is significant neck instability and moderate to severe ligament damage, a cervical neck brace, whether soft or metal, may be employed, a brace can restrict neck motion to promote ligament healing and lower the chance of additional harm.

- One must consider the possibility that a lack of movement could result in neck stiffness and muscular atrophy, which would eventually worsen and reduce the neck’s functionality.

- Therefore, bracing should only be done for a few days, for a very short time, or for about an hour each day if you’re doing something that puts your neck in greater danger of unanticipated motions, like driving on a bumpy road.

Surgical Treatment:

Only the most serious ligament injuries that have not responded to conservative measures should be treated with surgery. In the event that the ALL ligament injury resulted in nerve loss or spinal cord injury, surgery would also be necessary.

Anterior Fusion:

The most common surgical procedure for severe ALL injuries is anterior fusion. An anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion (ACCF) or anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) may be the precise procedure.

These procedures involve making an incision in the front of the neck, moving crucial structures to prevent harm, and then performing the surgery. It is possible to decompress any extra bone spurs that might be squeezing nerves, remove some or all of the disk, and fuse the front of the neck bone together using screws and a plate to maintain stability in that area.

Anterior Longitudinal Ligament Reconstruction:

Only in cases where the ALL is destroyed, an artificial disk is present, and that segment is unstable is this surgery typically carried out. During this procedure, an allograft usually a synthetic or cadaveric ligament is used to repair the ALL.

Posterior Decompression and Fusion:

A posterior neck fusion would be done infrequently. Here, the back of the neck is used for the surgery. The surgeon would use screws to fuse the joints and/or vertebral bodies and remove any bone spurs that were compressing the nerves. This would be taken into account in the event of an upper neck ALL injury that resulted in significant joint damage or craniocervical instability.

Surgical and Invasive Procedures:

Many people find success with fusion surgery, but all procedures include a high risk of bleeding, infection, chronic nerve damage, stroke, and even death. Additionally, fusion causes that level to become immobile, which puts undue strain on the levels above and below the fusion.

Adjacent segment disease is the term for the damage and suffering that can be caused to the disks, nerves, and joints by excessive stress at other levels. Usually, this calls for additional therapies and perhaps even more surgery down the road. Are there any ways to prevent these significant hazards and fix damaged ALLs in light of the significant risks associated with invasive treatment?

- Prolotherapy:

In order to start a healing response, prolotherapy involves injecting an irritating fluid that slightly damages the tissue. A hypertonic dextrose solution is the most widely used solution. For minor ligament and tendon injuries, it can be highly effective, but because of the limited healing response, it frequently takes several treatments.

This is frequently applied to injured posterior neck ligaments, including the interspinous and supraspinous ligaments. However, prolotherapy is usually not administered directly to the ALL. This is because the ALL is near numerous blood vessels, and if a prolotherapy injection is accidentally administered into a blood vessel that supplies a nerve or the brain, it may cause harm.

- Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) Injections:

PRP is created by centrifuging (spinning) the patient’s own blood to separate its constituent parts and then concentrating the platelets. Growth factors, cytokines, proteins, exosomes, and other substances are found in platelets and mediate a healing response. PRP can be administered into neck ligament injury and mild to moderately injured ligaments like the ALL.

This is frequently used to treat ALL injuries. PRP can also be utilized to assist cervical facet joints recover and reduce the progression of arthritis. Cervical disk tears that may cause pain or irritate nerves can also be treated with PRP.

Finally, by lowering inflammation and supplying healing growth factors to allow the nerve to heal itself, platelet lysate a particular kind of PRP that we produce in our lab can be utilized to treat inflamed nerves.

- Bone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate (BMAC):

Along with numerous other cells that have the potential to be potent repair cells, BMAC contains stem cells. Like PRP, bone marrow can also be extracted, ground up, and concentrated before being injected into the patient’s injured tissue.

For moderate to severe ligament and joint injuries, BMAC combined with stem cells is a more potent healing agent. This is frequently used to treat ALL and other neck injuries.

Prevention of Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL) Injury:

- Lifting objects correctly: To prevent stressing the anterior longitudinal ligament, it’s critical to employ safe lifting techniques while moving heavy goods.

- Avoid repetitive actions: Over time, repetitive motions, such as those found in some sports or occupations, can stretch the anterior longitudinal ligament. Regular stretching and breaks can help lower this risk.

- Treat underlying disorders: The likelihood of anterior longitudinal ligament injury can be decreased by treating underlying condition like osteoporosis or inflammatory diseases.

Complication of Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL) Injury:

Chronic pain, spinal instability, reduced range of motion, post-traumatic arthritis, and deformities like kyphosis or lordosis caused by changed spinal mechanics are all possible consequences of Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL) injury. If spinal cord or nerve compression develops in severe cases, especially when there are accompanying vertebral fractures, neurological impairments may result. Inadequate or delayed treatment can impair overall spine health and mobility by causing degenerative disc degeneration and long-term functional restrictions.

Prognosis:

The degree of damage and related spinal injuries determine the prognosis of an anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) injury. Conservative treatment for mild to severe sprains or partial rips, such as rest, bracing, and physical therapy, usually results in good healing; recovery takes six to twelve weeks.

A lengthy recovery period of several months to a year may be necessary for severe injuries, such as total tears or ruptures, which may call for surgical intervention such as spinal fusion. If left untreated, long-term effects may include degenerative changes, stiffness, or instability. The likelihood of a complete recovery is greatly increased by early diagnosis and suitable rehabilitation.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, spinal stability and movement can be affected by Anterior Longitudinal Ligament (ALL) injuries, which can vary in severity from minor sprains to major ruptures. Most people can recover functionally with immediate evaluation and adequate treatment, whether it is conservative care for small injuries or surgery for more serious situations.

On the other hand, degenerative spinal disorders, instability, or persistent pain could result from skipping treatment. For the best long-term results, proper rehabilitation and follow-up care are essential.

FAQs

What is the extent of the anterior longitudinal ligament?

Some fibers of the anterior longitudinal ligament run from one segment to the next, while others span up to five segments, connecting the sacrum to the cervical spine.

How does the anterior longitudinal ligament function?

The only ligament that keeps the spine from hyperextending is the anterior longitudinal ligament, which has multiple layers and supports the joints between the vertebral bodies.

What is the stronger longitudinal ligament?

Anterior longitudinal ligament

Compared to the anterior longitudinal ligament, the posterior longitudinal ligament is weaker and smaller. The oval shape of the PLL at the L5-S1 level ranges in width from 2 to 2.25 mm. The ligament creates a narrow band from L5 onward and symmetrically widens at each disc level.

The anterior longitudinal ligament is how long?

The ALL, a key spine stabilizer that is roughly an inch broad, extends from the base of the cranium to the sacrum via the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spines. It joins the front of the annulus fibrosis to the front (anterior) of the vertebral body.

What is the anterior longitudinal ligament disease?

The idiopathic rheumatological abnormality known as Forestier’s condition, or diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), is characterized by exuberant ossification along ligaments throughout the body, particularly the anterior longitudinal ligament of the spine.

How can an anterior longitudinal ligament injury be treated?

The severity of an anterior longitudinal ligament damage determines how it should be treated. While more severe cases may necessitate surgery to replace or repair the injured ligament, mild cases can be managed with rest, ice, and physical therapy.

What signs of injury to the anterior longitudinal ligament are present?

Anterior longitudinal ligament injuries can cause stiffness, restricted range of motion, and back pain. In extreme situations, nerve injury or spinal instability could occur.

Why may the Anterior Longitudinal Ligament get injured?

Trauma, such as a vehicle accident or fall, or repetitive strain, such as carrying heavy things or engaging in specific sports or work-related activities, can result in injury to the anterior longitudinal ligament.

The anterior longitudinal ligament stops which joint movement?

The main function of the ALL is to stop the spine from bending backward or extending excessively. By preserving spinal integrity during motions that put stress on the ligament, this function helps shield the spinal cord and nerves from compression or damage caused by overextension.

What occurs if there is damage to the anterior longitudinal ligament?

Loss of normal spine curvature, an elevated risk of vertebral fractures, and spinal instability can result from damage to the ALL. In addition to causing chronic back pain and decreased mobility, it may also make the spine more vulnerable to degenerative changes or additional injuries.

Where are the connection locations for the anterior longitudinal ligament?

From the sacrum to the axis (C2), the ALL connects to the anterior surfaces of the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs, maintaining spinal alignment and offering structural support.

What is the anterior longitudinal ligament’s main purpose?

Limiting excessive extension (backward bending) of the spine is the main purpose of the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL). By keeping the front aspect of the vertebral column supported and avoiding hyperextension, it contributes to spinal stability.

References

- Markle, J. (2025, February 17). Anterior longitudinal ligament injury: What you need to know. Centeno-Schultz Clinic. https://centenoschultz.com/the-cervical-anterior-longitudinal-ligament-all-injuries/

- Anterior longitudinal ligament injury treatment approaches. (2025, February 13). Centeno-Schultz Clinic. https://centenoschultz.com/treatment/anterior-longitudinal-ligament-injury-treatments/

- Patel, D. (2023b, August 22). Anterior longitudinal ligament – anatomy, structure, function. Samarpan Physiotherapy Clinic. https://samarpanphysioclinic.com/anterior-longitudinal-ligament/

- Physiotherapy, K., & Physiotherapy, K. (2024, August 23). Anterior longitudinal ligament: causes, symptoms, and treatments. Kamalika’s Physiotherapy. https://kamalikasphysiotherapy.in/anterior-longitudinal-ligament-causes-symptoms-and-treatments/