Brachial Plexus Block

The Brachial Plexus: What is it?

A brachial plexus block is a regional anesthesia technique used to numb the arm, shoulder, or hand by injecting local anesthetic near the brachial plexus—a network of nerves that originates from the spinal cord in the neck and controls movement and sensation in the upper limb. This block is commonly used for surgeries or procedures on the upper extremity, offering effective pain relief and reducing the need for general anesthesia.

A Brachial Plexus Block: What Is It?

One regional anesthetic method that is occasionally used in addition to general anesthesia for upper extremity surgery is brachial plexus block. This approach temporarily impairs upper extremity sensation and movement by administering local anesthetics near the brachial plexus. During the subsequent surgical process, the person may be kept awake or, if required, sedated or even wholly anesthetized.

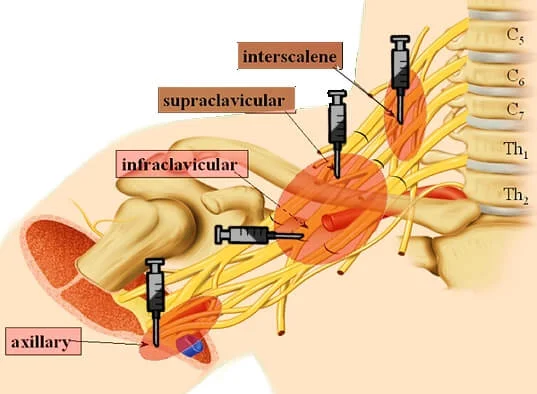

The brachial plexus nerves can be restricted using a variety of methods. These procedures are classified according to the level at which the local anesthetic is injected using a needle or catheter: The most thorough postoperative analgesia is believed to be an inter-scalene block on the neck, which is followed by axillary block in the axilla (armpit), supraclavicular block slightly above the clavicle, and infraclavicular block below the clavicle.

Anatomy of Brachial Plexus:

The brachial plexus is made up of the ventral rami of C5-C6, C7-C8, and T1, with some contribution from C4 and T2. The axillary, supraclavicular, and infraclavicular blocks are used to block the brachial plexus distally after the interscalene block, which is used proximally.

The premise behind all of these brachial plexus techniques is that a sheath enclosing the neurovascular bundle stretches from the deep cervical fascia to just outside the axillary boundaries.

Indications:

General anesthesia can cause low blood pressure, undesired reductions in cardiac output, central nervous system depression, respiratory depression, loss of protective airway reflexes (such as coughing), the requirement for tracheal intubation and mechanical breathing, and residual anesthetic effects.

Although all of the criteria listed below are satisfied, brachial plexus blockage may be an appropriate option:

- Surgery will only be performed in the region between the fingertips and the midline of the shoulder.

- There are no contraindications to a block, such as infection at the injection site, severe bleeding condition, anxiety, allergy, or intolerance to local anesthetics.

- There will be no need to assess the function of the blocked nerves immediately following the surgical treatment.

- The patient prefers this method to other accessible and fair options.

What benefits might one expect from having a brachial plexus block?

The risks connected to general anesthesia are minimized.

It is conceivable that your surgery will just require a brachial plexus block. This might be critical if you have heart or respiratory difficulties. There will be no pressure or pain during the process.

Besides a general anaesthetic, you may also have a block. It relieves pain after surgery, reducing the need for harsh painkillers. Starting to move your arm or hand during physiotherapy might also aid with rehabilitation.

A brachial plexus block improves blood flow to the damaged area. In some instances, this may promote healing and speed up your recovery.

Techniques:

Interscalene block

The interscalene block is achieved by administering a local anesthetic to the nerves of the brachial plexus as it passes through the groove between the anterior and middle scalene muscles at the level of the cricoid cartilage. For clavicle, shoulder, and arm surgeries, this block is very helpful in delivering anesthesia and postoperative analgesia.

The advantages of this block include quick shoulder blockage and anatomical markers that are very easy to palpate. One disadvantage of this block is that it provides insufficient anesthesia in the ulnar nerve distribution, making it unsuitable for forearm and hand surgeries.

Side effects

Almost everyone who has had an interscalene or supraclavicular brachial plexus block experiences temporary paresis (thoracic diaphragm function impairment). Pulmonary function tests can reveal significant respiratory impairment in some persons. In certain persons, such as those with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, this might lead to respiratory failure, necessitating tracheal intubation and artificial ventilation until the block resolves.

Horner’s syndrome may occur if the local anesthetic solution travels enlarged and inhibits the stellate ganglion. This can be accompanied by difficulties swallowing and vocal cord paralysis. These signs and symptoms, however, are temporary and seldom cause long-term difficulties, though they can be quite stressful for patients until the effects wear off.

Contraindications

Phrenic nerve paresis on the other side of the block and severe chronic obstructive lung disease are two examples.

Supraclavicular block

The supraclavicular block is perfect for procedures involving the arm and forearm, from the lower humerus to the hand, since it may quickly produce thick anesthesia of the arm with a single injection. Nerve block at the level of the trunks created by the C5–T1 nerve roots offers the highest chance of blocking all of the brachial plexus’s branches since this is where the brachial plexus is most compact. This results in rapid start times and, ultimately, high success rates for analgesic and upper extremity surgery, except for the shoulder.

This position is often lateral to (outside) the lateral edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and above the clavicle. Because the pleural cavity and the highest portion of the lung are positioned at this level, the first rib is commonly thought of as the boundary below which the needle must not be directed. The brachial plexus, which is lateral to the artery at this position, may be found anatomically by palpating or visualizing the subclavian artery slightly above the clavicle. One can employ ultrasound guidance, a peripheral nerve stimulator, or the Removal of paraesthesia to evaluate proximity to the brachial plexus.

Although the supraclavicular block produces a more thorough block of the median, radial, ulnar, and musculocutaneous nerves than the interscalene block, it does not enhance postoperative analgesia. The supraclavicular block is frequently easier to do and is probably less likely to cause adverse effects than the interscalene block. When it comes to successfully achieving appropriate anesthesia for upper extremity surgery, supraclavicular blocks are comparable to infraclavicular and axillary blocks.

Only 50% of patients who have supraclavicular block suffer from diaphragmatic hemiparesis, in contrast to all people who have interscalene block. One disadvantage of the supraclavicular block is the potential for pneumothorax, which is estimated to be between 1% and 4% when guided by peripheral nerve stimulators or paraesthesia. By enabling the operator to see the pleura and the first rib, ultrasound guidance helps to prevent the pleura from being punctured by the needle, which probably lowers the chance of pneumothorax.

Infraclavicular block

According to available data, a double-stimulation approach is superior to a single-stimulation approach for the infraclavicular block when utilizing a peripheral nerve stimulator for nerve localization. The effectiveness of multiple-stimulation axillary blocks is comparable to that of another infraclavicular block. On the other hand, the patient can have less pain throughout the process and a shorter performance time.

Axillary block

Because there is no risk of pneumothorax or phrenic nerve paresis, the axillary block is the safest of the four main techniques for entering the brachial plexus. The readily palpated axillary artery, therefore, serves as a reliable anatomical reference for this block, and the administration of local anesthetic adjacent to this artery typically leads to a satisfactory block of the brachial plexus. Because it is simple to do and has a comparatively high success rate, the axillary block is frequently used.

The axillary block’s insufficient anaesthesia in the musculocutaneous nerve distribution is one of its drawbacks. It could be required to block the musculocutaneous nerve individually if it is overlooked. This can be accomplished by employing a peripheral nerve stimulator to locate the nerve as it passes through the coracobrachialis muscle. Also often ignored by the axillary block are the intercostobrachial nerves, which are branching of the second and third intercostal nerves. Since these neurons supply sensation to the axillary skin as well as the medial and posterior portions of the arm, compression applied to the arm may not be well tolerated in certain circumstances. By blocking these nerves, a local anesthetic injected subcutaneously in the axilla over the arm’s medial area aids patients in tolerating an arm tourniquet.

Blocking in regions supplied by the radial and musculocutaneous nerves is unreliable with one-shot techniques. According to available data, the most effective method for axillary block is a triple-stimulation approach that involves injecting the musculocutaneous, median, and radial nerves.

Brachial Plexus Block Procedure:

A tiny needle will be used to inject a dose of local anesthetic into your neck, the region above your collarbone, or the upper upper arm. After that, your doctor could insert a tiny catheter into one of these areas. This would have allowed us to position you to provide medication more continuously and would have been discussed with you before the surgery. In certain cases, even when the medication is given in the right place, the patient may not feel any less pain. This is regrettable, but it could provide your doctor with useful information.

How Do I Get Ready for the Process?

Although the brachial plexus block is a safe medical technique, there are dangers and advantages to every operation. We suggest that you follow a few basic rules to reduce the likelihood of complications:

Six hours before the surgery, refrain from eating or drinking anything.

You must have a responsible adult driver accompany you to and from Stanford Ambulatory Surgery Centre. To reduce anxiety and alleviate some of the slight discomfort associated with the surgery, you will probably be given a modest dosage of intravenous medicine during the process. You must be accompanied by a capable adult driver since the intravenous drug you receive will affect your ability to drive.

What Takes Place Throughout the Process?

An intravenous line will be inserted first, usually in your hand. After that, we’ll take you to the operating room and attach a number of monitors to you, including ones for your heart, blood pressure, and pulse. We will be able to keep an eye on your vital signs during the process thanks to them. We will start giving you intravenous medicine to reduce anxiety and provide you with some pain relief after the monitors are placed.

After cleaning a small section of skin around your neck, collarbone, or upper arm, a local anesthetic is injected into the skin to reduce any pain associated with the procedure. Your doctor will use a tiny needle to deliver the drug after the precise location has been verified. The catheter will then be positioned appropriately if you and your doctor agreed beforehand to insert one for more continuous post-procedure medication delivery. In most cases, the actual procedure takes 20 minutes.

Patients may report experiencing a return of their typical shoulder or arm pain while using the drug. This is a comforting indication that the drug is working as supposed and that the feeling will pass shortly.

Post-procedure instructions:

Before you are released from the Ambulatory Surgery Centre, the recovery room nurse will review these with you in more detail. One of these rules needs to be to avoid using heavy machinery or driving for 24 hours after the procedure. This is advised since you may not be able to do these duties because of the intravenous medicine you got after surgery.

Additionally, some individuals have weakness in the obstructed arm or shoulder. Therefore, you must refrain from using this arm to move heavy things for 12 to 24 hours following the treatment.

Recovery:

The local anesthetic’s effects will persist for four to twenty-four hours, with an average of ten to twelve hours. Before utilizing your arm, please make sure you have complete strength and sensation in it.

Are there any Dangers?

It’s a standard practice carried out with the highest care for your security. However, there is a danger associated with every medical procedure. To reduce the danger of general anesthesia, your anaesthesiologist can advise doing this block.

Brachial plexus blocks are not usually completely effective. The local anesthetic may not always reach every nerve. The success percentage is also influenced by your overall body shape and the procedure you are undergoing. Your anesthetist will decide how likely it is that the block will work fully.

Risk due to local anesthetic

Local anesthetic allergies are possible. It is extremely uncommon and less common than allergies caused by general anesthetics. Because we consider your weight when determining how much local anesthesia you require, an overdose of anesthetic shouldn’t occur.

heart issues, or breathing issues are examples of serious issues, However, they are uncommon. Your anesthetist is prepared to handle these situations.

Risk to nearby structures

The following adverse effects may occur if the injection is administered to the side of your neck:

- a low voice

- droopy eyelid

- feeling faint.

You could occasionally find it difficult to breathe deeply or that it takes more effort than usual to breathe. All of them are transient and will disappear as soon as the block does.

There is a 1 in 1000 chance of lung injury if we inject near the collarbone. Permanent injury is quite uncommon, and we can typically handle this to keep you safe. You can learn more about this from your anaesthetist.

There is a small chance of bleeding from blood vessel injury with any injection. Direct compression or putting more fluids into a vein are two ways we can treat this.

If you use any blood thinners, please let your anaesthesiologist know.

Nerve damage

There is very little chance of irreversible nerve injury, and this risk applies to all injection locations. According to the greatest research available, 1 in 15,000 to 30,000 people may have nerve injury. The annual chance of dying on UK roads is 1 in 15,000, which is comparable to this.

Patients frequently experience numbness and/or tingling in the hand, shoulder, or arm. About 1 in 20 individuals have this, and it normally goes away after three weeks or, on rare occasions, up to three months.

Additional reasons for nerve injury:

These include the following and are not caused by the brachial plexus block:

- The harm caused by the procedure,

- such as the uncomfortable stance, puts strain on your nerves when you’re being anesthetized.

- Using compression on your arm while undergoing surgery can squeeze and sometimes harm your nerves.

- Oedema following your procedure.

- Other health issues, such as diabetes.

FAQs

What are the brachial plexus’s building blocks?

Anesthesia is successfully administered to the upper limb from the shoulder to the fingers by blocking the brachial plexus. The indication, the supposed operation or treatment, the patient’s body habitus, any medical comorbidities, and any unique anatomical variations all influence the brachial plexus blocking techniques.

What is the brachial block landmark?

Benchmarks for brachial plexus block using a low inter-scalene approach: (1) Clavicle. (2) The sternocleidomastoid muscle’s posterior border. (3) Jugular vein external. The scalene “groove” between the anterior and middle scalene muscles is where the palpating fingers are placed.

What is the purpose of a supraclavicular brachial plexus block?

An alternative or supplement to general anesthesia, the supraclavicular block is a localized anesthetic procedure used to reduce postoperative pain following upper extremity surgery (mid-humerus through the hand).

What side effects might a brachial nerve block cause?

Bleeding, infection, or the injection of drugs into a blood vessel, which may result in seizures, are additional hazards associated with this treatment. Because these dangers are so uncommon, your doctors will be keeping a close eye on your vital signs to prevent any consequences.

Which medications are used to block the brachial plexus?

Study Objective: Patients having upper limb procedures frequently receive brachial plexus block (BPB). The most used local anaesthetic for BPB is ropivacaine.

A celiac plexus block: what is it?

An injection for pain management into the celiac plexus, a network of nerves in the upper abdomen, is known as a coeliac plexus block. The therapy stops your brain from receiving pain signals from these nerves.

Which technique is most commonly applied to obstructions of the brachial plexus?

Signs. The most popular brachial plexus block for operations involving the hand, wrist, and forearm, as well as for vascular disorders and chronic pain syndrome, is the axillary brachial plexus block.

How long does a brachial plexus block last?

The brachial plexus block lasted two hours at its shortest and twelve hours at its longest.

References

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024f, July 26). Brachial plexus block. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brachial_plexus_block

- Complications. (2017, September 12). Stanford Health Care. https://stanfordhealthcare.org/medical-treatments/b/brachial-plexus-block/complications.html

- Brachial plexus nerve block – Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust. (2021, June 16). Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust. https://www.buckshealthcare.nhs.uk/pifs/brachial-plexus-nerve-block/