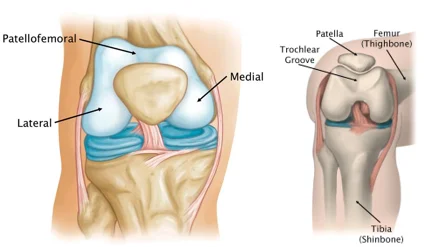

Patellofemoral Joint

The patellofemoral joint is a unique and complex structure composed of static (bones and ligaments) and dynamic (the neuromuscular system) elements. The patella is shaped like a triangle, having an inferiorly oriented tip. The primary articulating surfaces of the patellofemoral joint are the trochlea and the distal articulating surface of the femur, with which it articulates superiorly.

Introduction

The patellar surface of the femur and the posterior surface of the patella articulate to produce the patellofemoral joint, a plane synovial joint.

A triangular sesamoid bone, the patella has a sharp distal apex and a curving proximal base. It has articular cartilage covering its rear surface. The tendon of the quadriceps femoris muscle safely inserts and protects the patella. The patellar ligament is a thick band that runs from the patellar apex to the superior region of the tibial tuberosity on the distal portion of the patella. It is formed by an extension of the quadriceps tendon.

A groove on the anterior part of the distal femur that extends posteriorly into the intercondylar fossa is known as the patellar surface of the femur. In the anterior area, it articulates with the patella.

The medial and lateral patellofemoral ligaments reinforce the patellofemoral joint, preventing subluxation and dislocation of the patella and offering stability.

Anatomy

Osseous Structure/Cartilage

The posterior surface of the patella and the trochlear surface of the distal anterior femur make up the patellofemoral joint, a diarthrodial plane joint. The base is the superior surface, while the apex is the inferior patella.

The patella is made up of a trabecular core and a thin cortical shell. In both the medial-lateral and anterior-posterior axes, the patella’s anterior surface is convex. There are several distinct facets on the patella’s posterior side. The medial and lateral halves of this surface are separated by a significant vertical ridge. Three horizontal pairs—proximal, middle, and distal—as well as an odd facet on the far medial, posterior surface of the patella, can be separated into seven facets from the two halves.

With a larger lateral side to aid in maintaining patellar position, the convex patellar facets accommodate the concave femoral surface. A dense layer of articular cartilage, up to seven millimeters thick, covers most of the patella’s articulating surface. The substantial joint reaction forces produced by strong quadriceps muscle contractions are believed to be dispersed by this thick cartilage.

With concave lateral and medical facets covered by a thin layer of articular cartilage, the distal femur forms an inverted U-shaped intercondylar groove, also known as the trochlear sulcus. Similar to the patella, the femur’s larger, more proximal lateral facet serves as a bone support to improve patellar stability.

Radiographs (skyline view) that measure the angle between the lateral and medial femoral condyles can be used to identify a sulcus angle. This angle typically averages about 138 ± 6 degrees. Trochlear dysplasia, or a shallower trochlea, and a propensity for patellar subluxation would be indicated by a larger angle.

Soft tissue

The stability of the patellofemoral joint depends on both static and dynamic soft tissue components because of the shallow and incongruent fit between the patella and the trochlea. The ligamentous tissues, joint capsule, and patellar tendon provide static stability. The primary lateral constraint component, the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL), becomes essential in lowering lateral translation.

This ligament connects the medial border of the patella to the adductor tubercle. According to Desio et al.., the MPFL offers 60% complete restraint at 20 degrees of knee flexion. A secondary restraint is the medial mensicopatellar ligament, which connects with the medial patellar tendon and the medial collateral ligament through superficial fibers. It originates from the anterior aspect of the menisci and inserts into the inferior 1/3 of the patella and the medial retinaculum.

The lateral patellofemoral ligament, joint capsule, iliotibial band (ITB), and lateral retinaculum are the structures that contribute to stability on the lateral side of the patellofemoral joint. From the ITB to the patella and quadriceps expansion, the lateral retinaculum is composed of a thinner superficial layer. The patellofemoral ligament, patellotibial ligament, and vastus lateralis all connect with the thicker deep layer. At angles less than 20-30 degrees of flexion, the joint has little to no bone support and must rely on the medial and lateral retinaculum and joint capsule.

Patellar alignment is dynamically maintained by the contractile structure of the quadriceps, pes anserine muscle group, and biceps femoris muscle. There has been much discussion in the literature over the significance of the vastus medialis oblique (VMO).

The MPFL, adductor magnus tendon and the midsection of the patella are where the VMO is attached. It has a mechanical advantage to support the patella’s medial stabilizing force because of its more oblique orientation (in contrast to the vastus medialis longus). The superior aspect of the patella’s anterior region is where the rectus femoris inserts.

The patella’s base is where the vastus intermedius enters posteriorly. Alongside the superficial oblique retinaculum and the ITB, the vastus lateralis offers lateral dynamic reinforcement. Lateral tilt and/or gliding of the patella might be caused by tightness in the ITB. By attaching to the tibial tubercle, the patellar tendon secures the patella inferiorly.

Articulating Surfaces

The trochlear surface of the distal anterior femur and the posterior surface of the patella make up the patellofemoral joint, a diarthrodial plane joint. The patella is positioned distal to the quadriceps muscle bulk that makes up the patellar tendon, and it has the geometric shape of an upside-down triangle. The base is the superior surface, while the apex is the inferior patella. At its peak, the average patella is 4 to 4.5 cm in length, 5 to 5.5 cm in width, and 2 to 2.5 cm in thickness.

Patella

A sesamoid bone with a triangular form, the patella is coated in articular cartilage on its posterior aspect.

Similar to other joints, the patella’s articular cartilage is made up of a solid phase and a fluid phase that is primarily made up of collagen and glycosaminoglycans. The solid phase is slightly porous, and the fluid progressively redistributes itself inside the solid matrix when the articular surface is under load.

Thus, the cushioning effect of the articular cartilage and the low friction coefficient of articular surfaces are closely related to fluid pressure. The fluid phase loses pressure when the articular surfaces are damaged, which puts extra strain on the collagen fibers and increases their susceptibility to potential breakdown.

Intercondylar groove

The intercondylar (trochlear) groove articulates with the patella. The lateral facet of the intercondylar groove is steeper and more noticeable anteriorly than the medial facet, which helps secure the patella against excessive lateral pull.

Ligaments

The medial and lateral components of the patellofemoral joint are primarily stabilized by the patellar retinaculum.

- The Medial Patellofemoral Ligament (MPFL) starts on the medial femur and attaches to the patella and quadriceps tendon in a “sail-shaped” manner. Individuals have suggested using a double-bundled graft to replicate the structure of this complex because of its larger attachment than its origin. Kang and associates used the terms superior-oblique bundle and inferior-straight bundle to designate two MPFL fiber components.

- Although the authors did not yet know the clinical significance of this, they hypothesized that the bundles might play different functions as dynamic vs static stabilizers. Additionally, it has been reported that the two attachment points or bundles varied in length. According to research by Mochizuki and colleagues, the MPFL fibers’ length from the origin to the medial patella was 56.3+/-5.1 mm, while the quadriceps tendon’s length was 70.7+/-4.5 mm.

- An essential lateral stabilizer of the patella against medial subluxation or dislocation is the Lateral Patellofemoral Ligament (LPFL). The lateral patellofemoral ligament, according to some writers, is a noticeable thickening of the joint capsule between the patella and femoral epicondyle.

Muscles

The rectus femoris and the vastus group (vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, and vastus medialis) make up the quadriceps muscle, which is the biggest and strongest extensor muscle.

Twenty percent of the knee extension torque is produced by the rectus femoris, and eighty percent is produced by the vastus group.

Two different fiber routes can be seen in the vastus medialis. The vastus medialis longus (VML) and vastus medialis oblique (VMO) join to the quadriceps tendon at around 15 to 18 and 50 to 55 degrees, respectively. Patella stability against excessive lateral pull is provided by the VMO’s more oblique pull.

The vastus lateralis and the iliotibial band both aid in lateral tracking.

The patellofemoral ligament, the patellotibial ligament, and the retinaculum all further limit patellar motion.

Kinesiology/Biomechanics

Function

The patella serves a variety of purposes. Its main function is to act as a mechanical pulley for the quadriceps during the knee range of motion, as the patella shifts the direction of the extension force. As it is gradually extended, its contribution grows.

Huberti and Hayes assert that the patella plays a crucial role in the final 30 degrees of knee extension. Only 13% of the total knee extension torque is provided by the patella between 90 and 120 degrees of flexion, compared to 31% at full knee extension. Additionally, the patella serves as a bony shield for the anterior trochlea and prevents excessive friction between the quadriceps tendon and the femoral condyles because of its position between the femur and quadriceps tendon.

Static Alignment

The shape of the patella, the height of the lateral femoral condyle wall, and the depth of the femoral sulcus all affect the patella’s static alignment. When evaluating gross alignment, the patient is usually in a supine position. McConnell has developed evaluation standards, but there have been concerns raised about this method’s interreliability.

The patella normally sits halfway between the two condyles when the knee is fully extended in the frontal plane, though some sources indicate a small lateral deviation. The patella is most mobile in this position because it is above the trochlea, and there is little contact between it and the femur. The Q-angle is frequently used in clinical settings to determine the quadriceps muscle pull’s alignment.

The angle formed by the quadriceps’ line of pull (from the anterior superior iliac spine to the mid-patella) and a line joining the patella’s center and tibial tuberosity is known as the Q-angle. The typical Q-angle for men is 10–13 degrees, while for women, it is 15–17 degrees. A bowstring effect is believed to produce excessive lateral forces on the patella when the Q-angle is increased. The static Q-angle has not been linked to either patellofemoral kinematics or pain, according to recent research.

The patella’s apex rests at or just proximal to the joint line in the sagittal plane when the knee is slightly bent. The Insall-Salvati ratio is a more advanced technique for determining sagittal plane patellar position. With the knee bent to about a 30-degree angle, this measurement is the ratio of the patellar tendon length to the patellar height.

A ratio of approximately 1.0 is regarded as typical. An inferior patella, also known as “patellar baja,” might result from a shortened patellar tendon if the ratio is less than 0.80. The term “patella alta” refers to a ratio higher than 1.2. The patella is more likely to subluxate in this superior position because it takes longer for it to reach the bony constraint of the femoral trochlea.

The patella should also be aligned with the femur so that the superior and inferior borders are equally spaced.” Tilt” is the term used to describe any anterior or posterior patella surface deviation. These movements are defined in the sagittal plane by the position of the patella’s inferior pole, which can be either elevated (superior tilt) or depressed (inferior tilt). A patella that is tilted inferiorly can cause issues because it can pinch or irritate the fat pad beneath the patellar tendon.

When the patella is horizontal in the transverse plane, the lateral and medial borders should be equally spaced from the femur. Lateral patellofemoral compression syndrome may result from a lateral tilt, in which the medial border is higher than the lateral border.

The direction of the patella’s inferior pole describes how the patella rotates around an anterior-posterior axis. The inferior pole rotates medially when it is oriented toward the medial side of the knee and laterally when it is oriented toward the lateral side. A lateral tibial torsion or other underlying tibial torsion may be indicated by this rotational position.

Dynamic Movement /Kinematic

Understanding the patella’s dynamic movement, also known as patellar tracking, is more crucial for the clinician than evaluating static alignment. The active contraction of the quadriceps, the extensibility of the connective tissue surrounding the patella, and the geometry of the patella and trochlear groove all affect how the patella moves during tibiofemoral motion. The patella is a gliding joint that can move in several planes.

These motions consist of medial and lateral tilt, medial and lateral rotation, superior/inferior glide, and medial and lateral glide. When the quadriceps contract during tibiofemoral extension, a superior pull is created on the patella, causing superior glide, also known as patellar extension. Patellar flexion, which happens in tandem with tibiofemoral flexion, is an inferior glide.

In the frontal plane, lateral and medial glides are translations that match the tibiofemoral motion. The lateral edge of the patella approaches the lateral side of the knee during lateral glide, while the medial side approaches the medial edge of the knee during medial glide. A longitudinal axis is where tilt happens. The direction in which the reference facet is moving is described by tilts. The lateral posterior patellar facet moves closer to the lateral femoral condyle in a lateral tilt, whereas the medial posterior facet moves closer to the medial femoral condyle in a medial tilt.

Open chain

The distal insertion of the patellar tendon to the tibial tubercle causes the patella to follow the tibia’s path during open-chain knee motion. When knee flexion occurs, the patella glides inferiorly; when knee extension occurs, it glides superiorly. A quadriceps set should cause the patella to move about 10 mm to the front.

The patella’s articulating surface varies over the knee’s range of motion as the knee flexes. Along the patella, the contact point travels proximally, and along the femoral condyles, inferior-posterior. With increasing knee flexion, the overall patellar contact area pattern increases, distributing joint forces over a larger surface area. This force distribution helps people with normally aligned patellofemoral joints avoid the negative consequences of frequent exposure to high compressive forces.

In full knee extension, the patella rests on the suprapatellar fat pad and suprapatellar synovium, just proximal to the femur’s trochlea, according to multiple sources. At full knee extension, Powers et al.’s contradictory findings show that the patella and trochlea make contact. However, the patella’s stability is compromised due to the shallow trochlear groove, and instability is more likely to occur at this location.

The inferior aspect of the patella makes contact with the uppermost part of the femoral condyles as the knee starts to flex. The lateral femoral condyle and the lateral facet of the patella make the first contact, but after 30 degrees, the contact is evenly spaced on both condyle sides, with an estimated total contact area of 2.0 cm².

As the joint becomes more congruent, the contact area gradually grows from its initial small size. The superior half of the patella makes contact with a portion of the femoral groove at 60 degrees of knee flexion, which is marginally inferior to the contact area at 30 degrees. With increasing joint congruence, the contact area progressively grows. The estimated contact area is 6.0 cm2, and it keeps growing as the knee flexes to 90 degrees. The patella’s superior portion is currently making contact with a section of the femoral groove directly above the notch.

The superior aspect of the patella makes contact with the region of the femoral groove directly surrounding the intercondylar notch after 90 degrees and up to 120 degrees of knee flexion. The patella spans the intercondylar notch in deep flexion, with only the patella’s far medial and lateral edges making contact. The patella and the lateral surface of the medial femoral condyle only make articulating contact with the odd facet when the patella is fully flexed.

During tibiofemoral extension to flexion, the patella tracks lateral-medial-lateral motion in addition to superior and inferior motion. Since the patella stays comparatively centered on the trochlea during flexion, there is little excessive medial or lateral motion in a normal knee. It is significant to observe that the external rotation of the tibia causes the patella to sit slightly laterally during full knee extension. The estimated displacement in both the medial and lateral directions is approximately 3 mm.

The patella centers itself in the trochlear groove and glides medially as the knee flexes. The patella tilts medially 5–7 degrees from a laterally tilted position associated with the geometry of the femoral trochlear groove during knee extension from 45 degrees to 0. At about 30 degrees of flexion, the patella returns to the lateral side and continues to lateralize for the remainder of the knee flexion. It has been said that the motion follows a C-curve pattern.

When the knee is in extension and early flexion, the patella may be tilted laterally (lateral side down) in normal. This tilt is mild and regarded as “reducible” (the lateral border can be readily lifted off the lateral femoral condyle to make the patella horizontal).

Closed Chain

The femoral surface glides behind the patella as the femur rotates in the transverse plane because the patella is comparatively tethered within the quadriceps tendon during closed kinetic chain movements. The lateral facet of the patella approximates the lateral anterior femoral condyle when there is excessive femoral internal rotation. One risk factor linked to PFP has been suggested to be increased hip adduction/internal rotation. Clinically, the frontal plane projection angle has proven helpful in identifying faulty kinematics in PFP patients.

Patellofemoral joint reaction force (PFJRF)

The compression force that results from knee joint angle and muscle tension is known as the patellofemoral joint reaction force (PFJRF). The PFJRF divided by the patellofemoral joint contact area represents the actual stress applied to the patellofemoral joint; this is known as joint stress, which is expressed as force per unit area.

The articular tissue experiences less stress the larger the contact area between the patellar surface and femur. A small contact area and a high PFJRF cause high patellofemoral joint stress, which can be detrimental to the joint cartilage. Poor patellar positioning, which will be covered in the next section, can increase this stress.

The joint forces also change as a result of a shift in the lever system as the patella and trochlea’s contact points vary throughout the motion. As the knee flexes from 0 to 90 degrees in non-weight bearing, the contact area between the patella and trochlea increases, resulting in less patellofemoral stress. Open-chain exercises should be performed between 90 and 30 degrees of knee flexion to reduce the stress on the patellofemoral joint.

The PFJRF rises from 90 to 45 degrees when the foot is fixed, then falls as the knee gets closer to full extension. Stress on the patellofemoral joint and PFJRF can be extremely high during even the most basic daily tasks, not to mention during sports and leisure activities. 1.3 times body weight (BW) is the force during level walking, 3.3 times BW during stair walking, 5.6 times BW during running, and up to 7.8 times BW during a deep knee bend or squat, according to studies.

Clinical significances

In addition to being clinically significant in some orthopedic and sports medicine conditions, the patellofemoral joint (PFJ) is essential to knee biomechanics. Degenerative changes, pain, and instability can result from its malfunction. Some of the patellofemoral joint’s most important clinical implications are listed below:

1. Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS)

- A common cause of anterior knee pain is PFPS, also referred to as runner’s knee.

- Frequently linked to excessive strain, muscular imbalances, or patella malalignment.

- Squatting, climbing stairs, and extended sitting are among the activities that aggravate it.

2. Patellar Maltracking and Instability

- Dislocation or subluxation (partial dislocation) may result from poor patellar tracking.

- In young athletes, particularly those with trochlear dysplasia or patella alta, it is common.

- Tight lateral retinaculum or weakness of the vastus medialis obliquus (VMO) may be involved.

3. Patellofemoral Osteoarthritis (PFOA)

- Crepitus, stiffness, and pain can result from degenerative changes in the patellofemoral joint.

- Frequently results from aging, past trauma, or biomechanical anomalies.

- It can deteriorate knee function when combined with tibiofemoral osteoarthritis.

4. Chondromalacia Patellae

- Patellar articular cartilage deterioration and softening.

- Contributes to knee pain, swelling, and grinding.

- Common in people with patellar malalignment and young athletes.

5. Patellar Fractures

- Direct trauma (e.g., falls, sports injuries, car accidents) may cause it.

- Surgery might be necessary, particularly if it is dislocated or linked to an extensor mechanism failure.

6. Patellar Tendinopathy (Jumper’s Knee)

- Patellar tendon overuse injuries are frequently observed in athletes who jump.

- Causes pain at the patella’s inferior pole that gets worse when you move.

- It can develop into chronic tendinosis if left untreated.

7. Fat Pad Syndrome (Hoffa’s Syndrome)

- Anterior knee pain is caused by inflammation of the infrapatellar fat pad.

- This may be made worse by excessive kneeling or knee hyperextension.

8. Synovial Plica Syndrome

- Knee pain and clicking due to irritation of the plicae or synovial folds.

- Meniscal pathology is frequently misdiagnosed.

9. Osgood-Schlatter Disease

- Impacts teenagers, resulting in tibial tuberosity pain and swelling from repeated stress.

- The immature tibial growth plate is linked to the traction of the patellar tendon.

10. Surgical and Rehabilitation Considerations

- For patients with severe patellar arthritis, patellofemoral replacement is an option.

- The main goals of rehabilitation techniques are to strengthen the quadriceps, enhance hip function, and address biomechanical issues to avoid re-injury.

Summary

A thorough understanding of the forces and structures influencing patellofemoral function is essential to comprehend the wide range of clinical issues that can arise at the patellofemoral joint.

This knowledge can be used in the evaluation and examination of athletes as well as in the prescription of rehabilitation treatments to ensure that exercises are carried out in ranges of motion that put the least amount of stress on weak or injured structures.

FAQs

The patellofemoral joint: what is it?

The posterior surface of the patella and the trochlear surface of the distal anterior femur make up the patellofemoral joint, a diarthrodial plane joint. The patella is one of the body’s major sesamoid bones.

What other names are there for patellofemoral?

Anterior knee pain is frequently caused by patellofemoral syndrome (PFS). Patellofemoral pain syndrome, retropatellar pain syndrome, runner’s knee, lateral facet compression syndrome, and idiopathic anterior knee pain are some of their common names.

Is there a cure for patellofemoral?

Approximately 90% of people fully recover from patellofemoral pain and can return to their prior activities. Most active individuals respond well to nonsurgical interventions.

References

- Patellofemoral joint. (2024, March 13). Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/patellofemoral-joint