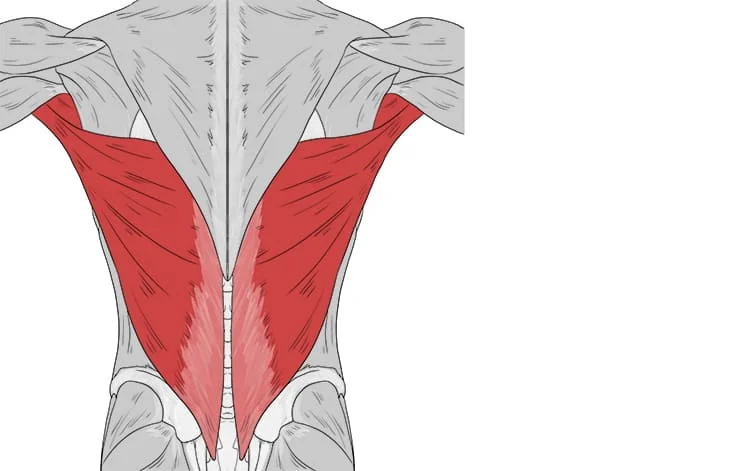

Latissimus Dorsi Muscle

The large, flat latissimus dorsi muscle occupies the majority of the lower posterior thorax. Although the muscle’s main job is to move the upper limb, it also serves as an auxiliary muscle for breathing. Owing to this muscle’s extensive attachment to the thoracolumbar fascia and several vertebral spinous processes, research on the muscle’s function in trunk movement is still underway.

What Is The Latissimus Dorsi muscle?

There is currently different evidence regarding the degree of influence this muscle has on rotation, lateral flexion, or spine extension. Using this muscle for surgical transposition appears to have a small decrease in normal function, despite the muscle’s strong actions on the humerus and broad attachment to the trunk.

Large and flat, the latissimus dorsi is located on the back, behind the arm, and to the sides. The trapezius muscle in the midline partially obscures it. Derived from the terms latissimus and dorsum, the Latin term latissimus dorsi suggests “broadest of the back.”. These two muscles are referred to as “lats” in general, particularly by bodybuilders.

The shoulder joint’s flexion from an extended posture, extension, adduction, transverse extension (also known as horizontal abduction or extension), and (medial) internal rotation are all controlled by the latissimus dorsi. It also works in tandem with the lateral flexion and extension of the lumbar spine.

Structure Of The Latissimus Dorsi muscle

One muscle that is thought to contribute to both thoracic and brachial (or arm) mobility is the latissimus dorsi. Before the trapezius attachment, the muscle is attached to the lowest six vertebral spinous processes.

The thoracolumbar fascia, the supraspinous ligament, and several lumbar and sacral spinous processes (T6 to S5) are where the latissimus dorsi attaches directly. The inferior angle of the scapula, the lower three to four ribs, where it interdigitates with the external oblique muscle, and the posterior iliac crest are additional muscle attachments.

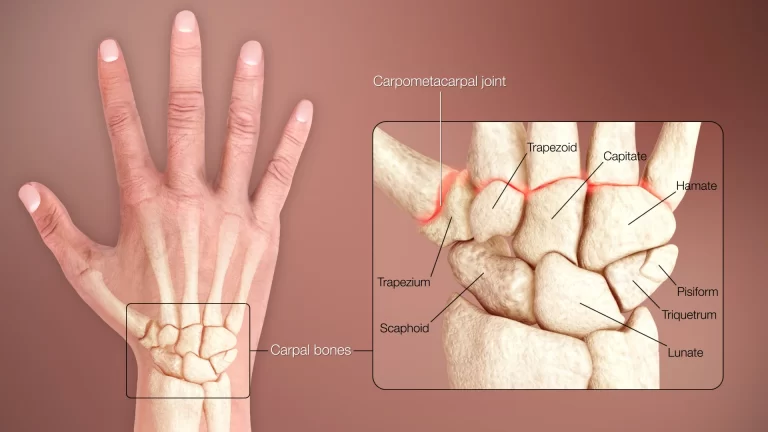

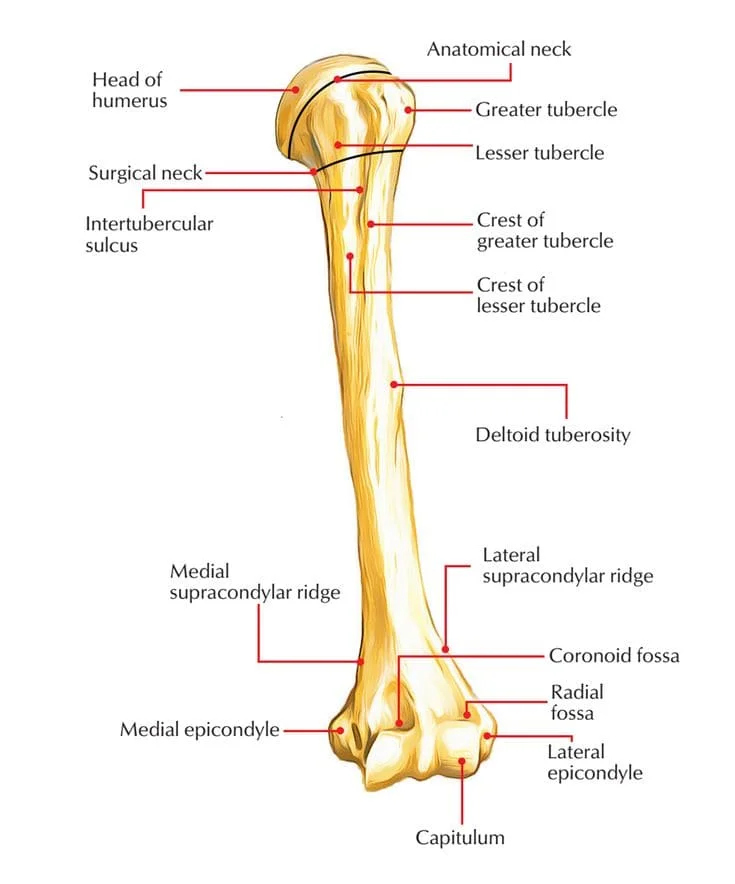

The orientations of the muscle fibers in the thorax, and the inferior fibers are more vertically oriented, while the superior-most fibers are nearly horizontally oriented. The muscle fibers spiral around the anterior portion of the teres major muscle as they extend toward the axilla, inserting as a flat tendon on the floor of the intertubercular sulcus.

The fascicles twist around one another as the fibers converge to implant on the humerus, placing the lower fibers to the midline higher in the sulcus and the most superior fibers to the midline on the lowest portion of the sulcus. Compared to the teres major attachment on the lateral lip, the latissimus dorsi attachment on the intertubercular sulcus extends more superiorly.

Variations

It is joined to four to eight dorsal vertebrae; it has a variable number of costal attachments; and muscle fibers may or may not extend to the crest of the ilium.

The axillary arch, a muscle slip that varies in length and width between 7 and 10 cm, can sometimes be seen originating from the upper edge of the latissimus dorsi around the middle of the posterior fold of the axilla. It then crosses the axilla in front of the axillary vessels and nerves, joining the fascia over the biceps brachii, the coracobrachialis, or the undersurface of the pectoralis major tendon.

This axillary arch may deceive a surgeon since it crosses the axillary artery slightly above the location often used for ligature application. It is found in roughly 7% of the population and is easily identified by the fibers’ transverse orientation.

Using MRI data, Guy et al. thoroughly defined this muscle variation and found a positive correlation between its presence and neurological impingement symptoms.

Typically, a fibrous slip extends from the long head of the triceps brachii to the upper border of the Latissimus dorsi tendon, close to its insertion.

This is the ape’s dorso epitrochlearis brachii representation, and it is occasionally muscular. This muscle type, sometimes known as the latissimo condyloideus, is present in approximately 5% of humans.

The latissimus dorsi passes over the scapula’s inferior angle. According to a study, out of 100 cadavers that were dissected:

The latissimus dorsi of 43% of participants exhibited “a substantial amount” of muscle fibers arising from the scapula.

In 36% of cases, a “soft fibrous link” connected the latissimus dorsi and the scapula instead of many or any muscle fibers.

Two structures in twenty-one percent of cases had little or no connective tissue.

Triangles

The lateral border of the latissimus dorsi is separated from the obliquus externus abdominis below by the Petit lumbar triangle, which has the iliac crest as its base and the obliquus internus abdominis as its floor.

Behind the scapula lies another triangle. Its lateral boundary is the vertebral border of the scapula, the trapezius forms its upper barrier, and the latissimus dorsi forms its lower boundary. The floor includes the rhomboideus major.

The sixth and seventh ribs, as well as the area between them, become subcutaneous and auscultatory when the scapula is pushed forward by folding the arms across the chest and the trunk bowed forward. The region is so known as the auscultation triangle.

The phrase “A Miss Between Two Majors” aptly describes the latissimus dorsi. Two primary muscles surround the latissimus dorsi as it penetrates the floor of the humerus’s intertubercular groove. On the medial lip of the intertubercular groove, the teres major inserts medially, while the pectoralis major inserts laterally onto the lateral lip.

Function Of The Latissimus Dorsi muscle

The latissimus dorsi aids in the teres major and pectoralis major’s assistance in arm depression. The shoulder is adducted, stretched, and internally rotated. The latissimus dorsi pulls the trunk forward and upward when the arms are fastened overhead.

It functions as a muscle of both forced expiration (anterior fibers) and an accessory muscle of inspiration (posterior fibers), working in concert to facilitate the lumbar spine’s extension (posterior fibers) and lateral flexion (anterior fibers).

Along with several other stabilizing muscles, the majority of latissimus dorsi movements also engage the teres major, posterior fibers of the deltoid, and long head of the triceps brachii.

Compound workouts for the ‘lats’ typically target the biceps muscles of the brachii, brachialis, and brachioradialis for elbow flexion. Depending on the direction of the pull, the trapezius muscles can also be employed; horizontal pulling exercises such as rows effectively activate the latissimus dorsi and trapezius muscles.

The latissimus dorsi collaborates with the teres major and pectoralis major muscles via the anterior attachment on the humerus to medially rotate and adduct the humerus. The teres major and latissimus dorsi work together to actively extend the humerus.

Starting at a partial flexion or abduction position, or a mix of the two, results in the strongest extension and adduction. When the upper extremities are fastened overhead, as in climbing or executing a chin-up, the muscle is actively moving the trunk anteriorly and superiorly.

Studies have shown that the latissimus dorsi is also engaged in vigorous respiratory processes like coughing and sneezing, as well as deep inspiration.

Training

Numerous workouts can be used to train this muscle’s growth, strength, and power.

Three of these are included in this:

- Pulling vertical exercises, such as chin-ups and pull-downs

- Pulling horizontal exercises, including the T-bar row, bent-over row, and other rowing workouts

- Straight-arm shoulder extension exercises like pull-overs and straight-arm lat pulldowns Deadlift.

Origin

The latissimus dorsi muscle covers the lower lumbar and thoracic regions on the back. This muscle can be divided into four distinct segments based on its origin:

Vertebral component: derived from the thoracolumbar fascia and the spinous processes of the seventh through twelfth thoracic vertebrae

Costal part: originating from the ninth to the twelfth ribs

Iliac part: commencing at the iliac crest

Scapular part: beginning at the scapula’s inferior angle

insertion

The proximal humerus is where all of the fibers converge. The lower vertebral and iliac fibers run obliquely, the costal fibers almost vertically, and the higher vertebral and scapular fibers almost horizontally.

The fibers spiral around the teres major muscle at this position, with the latissimus dorsi insertion more distally at the higher section and proximally at the humerus at the lower part. Between the pectoralis major and teres major on the humerus, all fibers collectively adhere to the bottom of the intertubercular sulcus.

‘Lady between two majors’ is a handy mnemonic to help you recall the relationship between the latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major, and teres major muscles as they insert in the intertubercular sulcus:

Lady: Latissimus dorsi

Majors: Teres major, pectoralis major

Nerve Supply

The latissimus dorsi is innervated by the thoracodorsal nerve, which is a branch of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus (C6 to C8, with C7 predominate).

Together with the thoracodorsal artery and the veins that supply it, the nerve will pass through the neurovascular bundle. There is a close relationship between the artery and nerve branches.

Action

The latissimus dorsi works as part of the teres major and pectoralis major to perform movements of the upper extremities. These muscles will work together to rotate medially, adduct the arm, and extend it at the glenohumeral joint.

The latissimus dorsi, teres major, and sternal heads of the pectoralis major and teres major all contribute to the humerus’s extension.

Partial flexion, abduction, or a mix of the two positions will result in the strongest extension and adduction.

Additionally, studies have shown that the latissimus dorsi is engaged during vigorous respiratory movements including coughing and sneezing as well as deep breathing.

Blood Supply

The thoracodorsal artery, a continuation of the subscapular artery, a branch of the third section of the axillary artery, supplies the latissimus dorsi muscle primarily.

On the anterior surface of the muscle, the thoracodorsal artery and its venae comitantes enter the muscle at a single location 6–12 cm from the subscapular artery bifurcation and 1–4 cm medial to the muscle’s lateral border.

The inferior three posterior intercostal arteries and the superior three lumbar arteries’ dorsal perforating branches deliver blood to the latissimus dorsi in addition to the thoracodorsal artery.

Lymphatics

This muscle’s lymphatic drainage system drains into the posterior group of six to seven axillary lymph nodes, which are situated along the subscapular veins on the inferior edge of the posterior axillary wall. The lymphatic drainage system of this muscle follows the standard pattern, with superficial and deep lymphatics.

The skin and superficial muscles from the inferior part of the neck to the iliac crest are drained by the afferent lymphatic veins that supply these nodes. These nodes’ efferent arteries empty into the central and apical axillary nodes.

Related Muscles

To execute upper limb movements, the latissimus dorsi collaborates with the teres major and pectoralis major. These muscles will work together to rotate medially, adduct the arm, and extend it at the glenohumeral joint. When testing the latissimus dorsi muscle, the subject is in the prone position with their arm and elbow completely extended. Abduction and slight flexion cause resistance in the forearm.

When the upper extremity is flexed into an overhead posture, such as reaching for something on a high shelf, the latissimus dorsi will cause the back to extend and rotate in short or tight. The upper extremities can be positioned overhead thanks to the spine’s ability to accommodate extension and rotation.

Embryology

As an extrinsic muscle of the back, the latissimus dorsi does not originate from the myotomal dorsal epaxial division of the somite, which is where the intrinsic (deep back) muscles do. Rather, it arises from the myogenic cells in the developing upper limb buds.

From an embryological perspective, the latissimus dorsi and teres major muscles are closely connected since they both come from the arm’s pre-muscle sheath.

As the myoblasts migrate posteriorly from the limb bud into the axial mesenchyme, the latissimus dorsi expands throughout the posterior region of the thorax and trunk.

The fibers of the latissimus dorsi do not reach the iliac crest until the embryo is at least 20 mm long, while the teres major is fully grown by the time the embryo is 14 mm long.

Anatomical Variation

There could be several latissimus dorsi variations. Between the latissimus dorsi’s axillary border and the axillary arteries and nerves, as well as connecting to the pectoralis major tendon, coracobrachialis tendon, or biceps brachii fascia, there may be a muscular arch.

Additionally, there can be a fibrous link between the long head of the triceps brachii and the tendon of the latissimus dorsi around its insertion point. While there might be other varieties, these are the most prevalent ones.

Surgical Considerations

For reconstructive procedures, the latissimus dorsi is commonly employed as a myocutaneous flap. As early as 1978, it was utilized for head and neck reconstruction surgery as well as post-mastectomy and chest wall reconstruction. A few benefits of employing this muscle for reconstructions are its vast volume of tissue, little donor site morbidity, and long vascular pedicle.

Using this muscle for reconstructions results in minimal functional losses in adduction or medial rotation, provided that the other muscles involved in those movements are preserved.

However, loss of the latissimus dorsi muscle could result in undesired functional restrictions in mobility if the patient needs shoulder movement and latissimus dorsi muscular function for ambulation with crutches or utilizing a wheelchair.

Clinical Significance

In patients who have limitations in their shoulder’s abduction, flexion, and lateral rotation, the latissimus dorsi may be involved. This muscle needs to be evaluated while assessing a patient with upper extremity pathology.

The teres major and pectoralis major muscles must work properly for the upper extremities to move smoothly and fluidly. For those with low back pain, the latissimus dorsi should be measured for length and flexibility because of its attachments to the spine and pelvis.

This muscle can change in length or stiffness, which can cause changes in posture and/or movement patterns that worsen lower back pain.

After seizures or electrical shocks/electrocutions, the latissimus dorsi may be involved in posterior shoulder dislocations. The external rotators are outmatched by the strong internal rotators of the arm, which include the latissimus dorsi, pectoralis, and subscapularis. This results in internal rotation of the shoulder with posterior and superior displacement.

Extensive research has shown that tight latissimus dorsi affects both chronic shoulder pain and chronic back pain. Tension in the latissimus dorsi muscle, which connects the humerus to the spine, can result in the inadequate function of the glenohumeral joint (shoulder), which causes persistent discomfort, or tendinitis in the tendinous fasciae that join the lumbar and thoracic spine to the latissimus dorsi.

The latissimus dorsi may be used as a source of muscle for pectoral hypoplastic abnormalities such as Poland’s syndrome or breast reconstruction surgery following a mastectomy (e.g., Mannu flap). One of the concurrent signs of Poland’s syndrome could be an absent or hypoplastic latissimus dorsi.

Cardiac support

In patients with low cardiac output who are not good candidates for heart transplantation, a procedure called cardiomyoplasty may be used to sustain their failing heart.

Injury

Lesions affecting the latissimus dorsi are uncommon. Baseball pitchers are disproportionately affected by them. A diagnosis can be made through muscle visualization and movement testing. An MRI of the shoulder girdle will confirm the diagnosis

For muscle belly injuries, rehab is the go-to treatment; for tendon avulsion injuries, surgery or rehabilitation are the options. Patients usually return to play without any functional deficits, regardless of the course of treatment.

Physical Therapy

Latissimus dorsi may be the cause of a patient’s limited capacity for abduction, flexion, or rotation laterally. This muscle needs to be evaluated while assessing a patient with upper extremity pathology. The teres major and pectoralis major muscles must work properly for the upper extremities to move smoothly and fluidly.

The back’s latissimus dorsi are a crucial component. When done correctly, lat exercises have many wonderful benefits. In addition, bodybuilders, who should be aware of the benefits of strengthening their back muscles, other advantages for everyday movement and life in general come with developing back muscles. One strength exercise is the chair-assisted chin-up for beginners.

The latissimus dorsi should be measured for length and flexibility in people suffering from low back pain because of its linkages to the spine and pelvis. Changes in movement patterns and/or postures caused by a reduction in the length or an increase in stiffness of this muscle may intensify the lower back pain.

Assesment of Latissimus Dorsi muscle

Palpation

The posterior border of the axilla is formed by the lateral side of the latissimus dorsi muscle. The arm is thought to contract when it is resisted. It is placed anteriorly at the crest of the smaller tuberosity.

Latissimus dorsi can be forced to protrude about the thorax by requesting a patient to elevate his or her arm to 90% flexion and keep it firm against an upwardly directed push.

Muscle Testing

When testing the latissimus dorsi muscle, the subject is in the prone position with their arm and elbow completely extended. Abduction and slight flexion cause resistance in the forearm.

The back will stretch and rotate when the upper extremity is flexed into an overhead posture, such as reaching for something on a high shelf if the latissimus dorsi is short or tight.

The achievement of the upper extremity position mentioned above is made possible by the spine’s accommodation of extension and rotation.

Exercise

Stretching Exercise Of The Latissimus Dorsi muscle

Child’s Pose

- Crawl to a starting point.

- Place the top end over your ankles.

- Put both of your arms out in front of you as far apart as you can.

- Retain a rounded lower back.

- For 30 seconds, hold.

- Stretch out both arms to the other side, one Latissimus Dorsi at a time.

Side Lie On Exercise Ball

- Using an exercise ball, lie on your side.

- To keep your balance, place your feet close to a wall.

- With the arm extended to the top side, reach over.

- For 30 seconds, hold.

Lat Stretch While Sitting

- With a table in front of you, take a seat in a chair.

- Put both of your elbows on the table’s edge, pointing forward.

- Shift your hips out of line with the table.

- Permit your chest to droop.

- For 30 seconds, hold.

Side Bend With Resistance Band

- Grasp a thick resistance band that is fixed higher than your head.

- Stretch your arm out in front of you in the other direction.

- Remain away from the anchor point until the band is tightly tensioned.

- As you place your entire body weight on the resistance band, let your arm relax.

- You should place the majority of your weight on the leg that is farthest from the resistance band.

- Put your pelvis in a twist.

- For 30 seconds, hold.

Door Frame Lean

- Take up the above position.

- With your hand, grasp a door frame.

- As you anchor your legs as demonstrated, try to flex your midsection as much as you can.

- As you sink into the stretch, use your body weight.

- Put your pelvis in a twist.

- Try to feel your side body getting stretched.

- For 30 seconds, hold.

Side Lie Stretch

- Put yourself on your side.

- Put your elbow up against the plush couch’s side.

- Permit your body to droop toward the ground.

- Stretch your lower leg apart from your torso.

- For 30 seconds, hold.

Strengthening Exercise Of The Latissimus Dorsi muscle

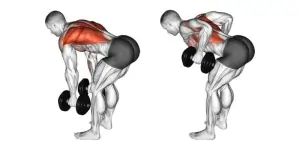

Dumbbell Row

Place the knee of the person on the other side of your working arm on a weight bench that has a moderate to heavy dumbbell lying next to it. Additionally, place your non-working palm on the bench.

firmly “spike” your rear foot out to the side or into the floor behind you. Put your core in a brace.

After grabbing the weight with your working arm, inhale deeply from your abdomen.

Dumbbells should be rowed up until your upper arm is parallel to your torso. Then, carefully lower the weight back down such that it stays off the ground.

Straight-Arm Pulldown

Attach a straight bar or rope to the carabiner and adjust the cable so that it is around eye level.

To get the cable to pull taut off the stack, grab the attachment and take a backward step of around two steps.

With your arms straight and held out in front of you, they should be almost perpendicular to your torso.

From here, without bending your elbows, brace your core and draw the attachment you’re holding down toward your hips.

Dumbbell Pullover

Seated on the end of a weight bench, grab a dumbbell.

Remain seated and recline on the bench. Hold the insides of one dumbbell end in your palms while extending your arms straight up and keeping your elbows straight.

Proceed to progressively lower the dumbbell behind your head while keeping your elbows straight.

If your shoulder mobility allows, after your arms are parallel to your torso, reverse the motion and engage your lats to return the dumbbell to its original position.

Barbell Row

Using a double-overhand or double-underhand grip on a barbell, stand straight with your feet beneath your hips.

Taking a deep breath, you should pivot your hips so that the bar falls to hang just below your kneecap.

From this position, brace your core; your torso ought to be nearly parallel to the ground.

As you raise the barbell toward your lower abdomen, hold your breath.

Seated Cable Row

Settle into a seat on the row station and place a close, neutral grip on the handles.

To tighten the cable, return to the bench and scoot. Sit up straight with your core braced, and let the weight draw your shoulders forward.

Pull your elbows backward and down as you row the handle (or handles) toward your body.

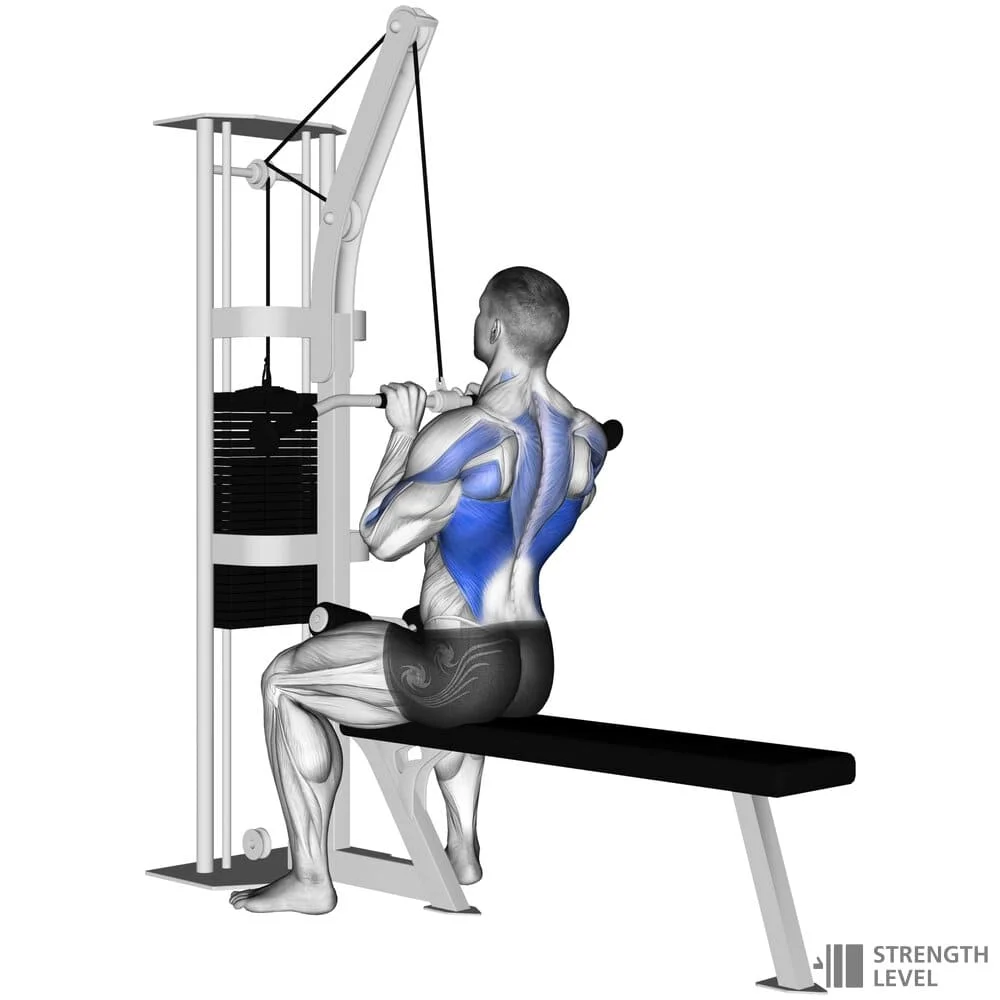

Close-Grip Pulldown

A close-grip handle is attached to the carabiner of a lat pulldown station once its weight has been adjusted to a modest level of difficulty.

Taking a seat at the lat pulldown station, place your thighs firmly against the pad while holding onto the handles with both hands.

Squeeze your shoulders together at the bottom and press your elbows into your back pockets while you very slightly lean back and draw the cable downward.

WIDE GRIP PULL-UP

Avoid spreading your arms too far; starting from the hanging posture, they should form a Y. You will still receive excellent lat activation if you move your hands in closer if this is too difficult.

Make sure your core remains active.

Draw your scapula down and together from a dead hang to elevate your body a little. Afterward, bring your elbows down toward your torso to raise yourself.

When your chest is as close to the bar as it can get and your chin is above it, stop. At the summit, avoid letting your shoulders curve forward and losing form.

You should always have your head facing forward.

For optimal results and lat development, perform each rep using your whole range of motion.

KROC ROW

With a dumbbell in your left hand (neutral grip) and your left leg aligned with your hips (including the knee of the supported leg), place your right hand and right knee on the bench.

Shoulders and hips should be in little elevation.

Thus, for the Kroc row, at a 15˚ inclination from parallel.

Pull your elbow back and up until your elbows are fully contracted while your left arm is extended. With Kroc rowing, momentum is an asset.

At the top, squeeze as hard as you can, and then gradually drop your arm to its maximum extent.

To prevent slouching, always maintain your hips and core engaged.

For the duration of the workout, your torso and hips must be squared forward.

SEATED UNDERHAND ROWS

Assume a posture in which your upper body is completely straight.

If you need to sit back more, then do so. Your arms should be completely extended when grasping the handle (with your underhand grip).

As much as you can, bring your elbows back; your arms should be fully extended in the final range.

When you row, avoid bending your torso backward.

There is only shoulder and arm movement.

After tensing up your lats to the maximum extent possible, slowly extend your arms again.

UNDERHAND INVERTED ROWS

With your hands shoulder-width apart, take an underhand hold beneath the bar.

To ensure that your body is fully straight, spread your feet apart.

If you want to make it harder, put your feet up on a platform.

Pull your elbows down to raise your torso toward the bar while keeping your arms completely extended. Retract your shoulder blades.

Raise your torso until the bar makes contact with your lower chest and upper abs.

Return your body to its starting position very slowly, until your arms are fully extended.

LAT PUSHDOWN

Assemble a straight bar attachment for a cable pulley machine.

Spread your hands somewhat wider than the breadth of your shoulders.

Move a few steps away from the machine so that when you begin with your arms raised, your back and legs feel stretched and tense.

Press the bar down toward your hips while maintaining a rigid body and fixed arms.

Firmly flex your back at the bottom, then slowly raise your arms back to the beginning position.

LAT PULLOVER

This is a two-way exercise. In one, your back is supported by the bench, and in the other, it is supported by the side of the bench.

See the latter in the dumbbell form below.

Start by grabbing an EZ bar or barbell with an overhand grip that is shoulder width apart.

Then immediately lower the bar again. Your elbows should only be slightly bent; otherwise, your arms should be straight.

Extend your arms as far behind you as is comfortable for you. Your goal is to have your lats’ stretching tension feel wonderful.

CLOSE GRIP CHIN UP

Hold out your hands with an underhand grip, about three to five inches apart.

Keep your arms outstretched and hang.

Pull yourself up until your chest meets the bar, making sure your shoulders are always tucked in and away from your ears.

If you are able, hold the highest posture for a brief period before lowering yourself to a full hang.

As you lift yourself, really feel your last contract.

WIDE GRIP CABLE LAT PULLDOWN

Remember to keep your torso as erect as possible, much like in a pull-up.

From the beginning position, your arms should form a Y.

If necessary, move the seat down so that your arms are extended from the beginning position. At the bottom, you should be able to feel your lats stretching.

Pull down on the bar while pulling your shoulder blades down and together to begin the exercise. Next, push your elbows down to your sides.

Throughout the workout, maintain a straight head and a strong core.

During the eccentric period, move gently (the upward motion).

Conclusions

Large and flat, the latissimus dorsi muscle stretches into the sides of the body and crosses the lower back. It is important for several shoulder and upper body movements.

When summed up, the latissimus dorsi muscle is a strong and adaptable muscle with important effects on posture, strength, mobility, and rehabilitation. One must comprehend its anatomy, function, and training concepts to maximize performance and avoid injuries.

FAQ

What is an interesting fact about the latissimus dorsi?

The latissimus dorsi is a triangular-shaped, thin, wide muscle that is under each arm and on either side of the back. Among the fascinating details of this muscle are: After a mastectomy (breast removal), the latissimus dorsi muscle fibers can be used to regenerate breast tissue.

How does the latissimus dorsi get its blood supply?

An outgrowth of the axillary artery, the subscapular artery provides blood to the latissimus dorsi muscle. A posterior circumflex scapular branch emerges from the subscapular, followed by a serratus branch that enters the muscle’s substance on the underside as the thoracodorsal artery.

Which muscle is the latissimus dorsi’s antagonist?

One of the deltoids’ adversaries is the latissimus dorsi. The deltoids execute the opposing actions, such as abductions, flexions, and external rotations of the humerus, to the lats’ adductions, extensions, and medial rotations of the upper arm.

Do pushups work lats?

Push-ups do engage your lats to some extent, primarily to maintain proper form and stability in your shoulders. However, push-ups are ineffective if your goal is to especially strengthen your lats. Try workouts like Lat Pulldowns, Pull-Ups, and Rows to improve your lat workout.

What are the benefits of the latissimus dorsi?

The largest muscle in the upper body, the latissimus dorsi, or “lat,” is a key component of your back and can assist you in performing intense exercises like pull-ups. Trainers must focus on this muscle during workouts because it also affects posture and shoulder health.

What is the main function of the latissimus dorsi muscle?

The pectoralis major and teres major work in tandem with the latissimus dorsi to help lower the arm. The shoulder is adducted, stretched, and internally rotated. The latissimus dorsi pulls the trunk forward and upward when the arms are fastened overhead.

What is latissimus dorsi exercise?

These muscles run from the back of the shoulder to the hips and are found on either side of the back. Pulling actions, such as opening a door or performing a pull-up exercise, use the lat muscles. Because of the movement, most lat exercises involve a pulling or rowing motion.

What are the 4 parts of the latissimus dorsi?

Vertebral component: Thoracolumbar fascia, spinous processes of vertebrae T7–T12.

The posterior third of the ilium’s crest is the iliac part.

Costal part: Ribs 9-12.

Scapular part: Inferior angle of scapula.

How do you relieve latissimus dorsi pain?

exercising and playing sports with the appropriate form.

avoiding using the muscle excessively.

Before working out, apply a heating pad to the affected area.

pre- and post-workout warming and cooling down.

Before cooling down and after warming up, gently stretch.

maintaining fluids.

get massages on occasion.

How painful is the latissimus dorsi?

Pain in the lower back, mid-to-upper back, along the base of the scapula, or in the rear of the shoulder might result from latissimus dorsi injury. Pain could even radiate down the inside of your arm to your fingertips.

4 Comments